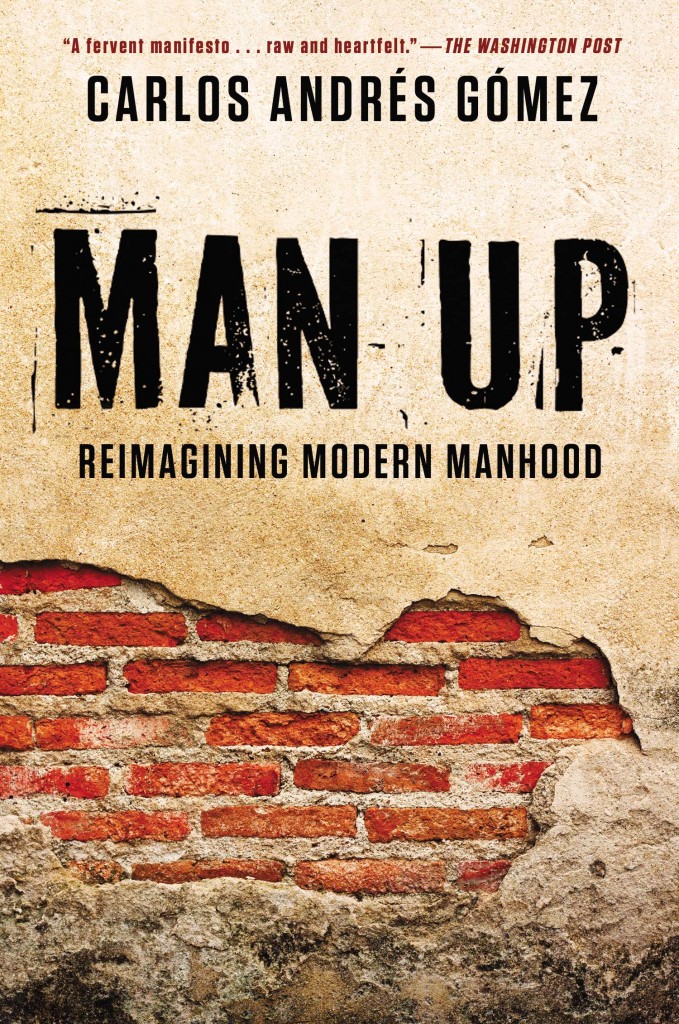

Carlos Andrés Gómez is a Colombian American writer from New York City. He is the author of the full-length poetry collection “Fractures” (University of Wisconsin Press, 2020), selected by Natasha Trethewey as the winner of the 2020 Felix Pollak Prize in Poetry; the chapbook “Hijito”(Platypus Press, 2019), selected by Eduardo C. Corral as the winner of the 2018 Broken River Prize; and the memoir “Man Up: Reimagining Modern Manhood” (Penguin Random House, 2012). His honors and awards include the Sandy Crimmins National Prize for Poetry, the Foreword INDIES Gold Medal, the Fischer National Poetry Prize, the Lucille Clifton Poetry Prize, the Atlanta Review International Poetry Prize, and the International Book Award for Poetry, as well as fellowships from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Voices of Our Nation Arts Foundation, and the Jerome Foundation. Gómez has been published in New England Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, The Yale Review, BuzzFeed Reader, CHORUS: A Literary Mixtape (Simon & Schuster, 2012), and elsewhere. Carlos is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College. For more, please visit CarlosLive.com.