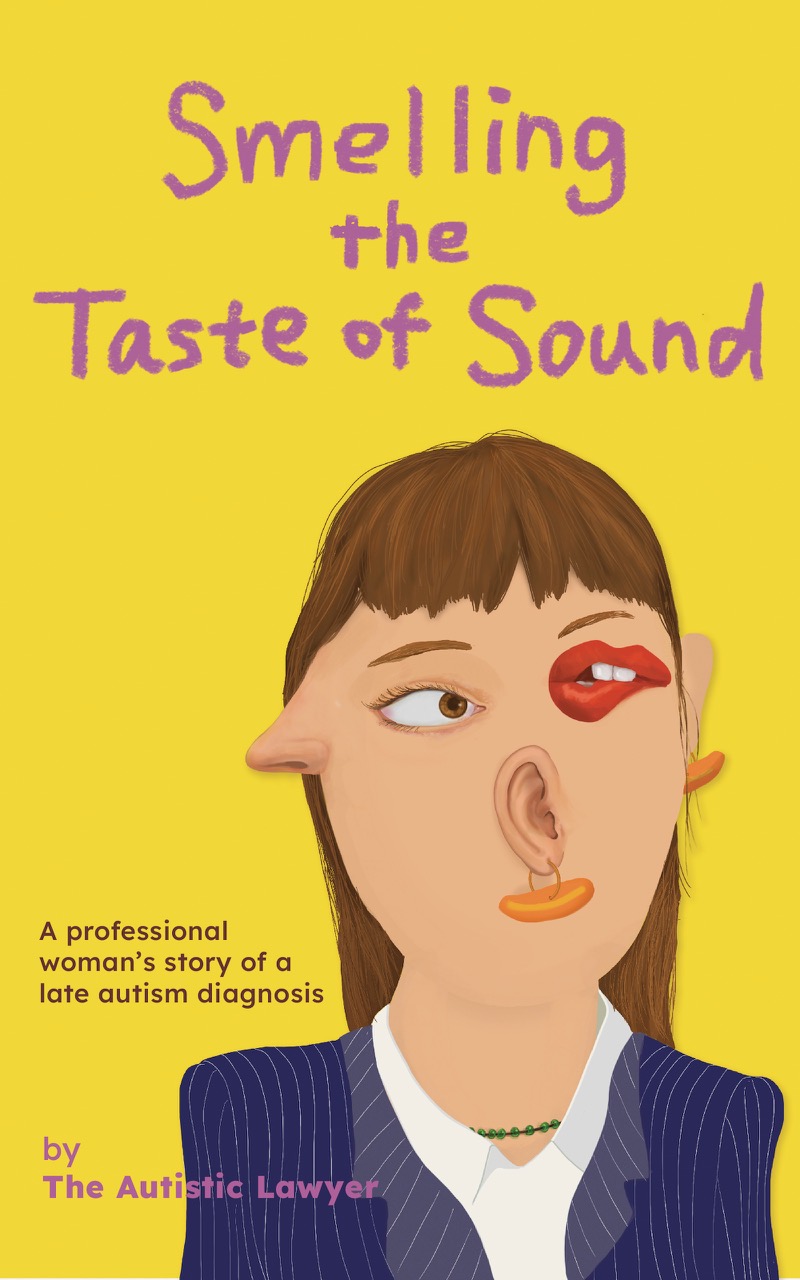

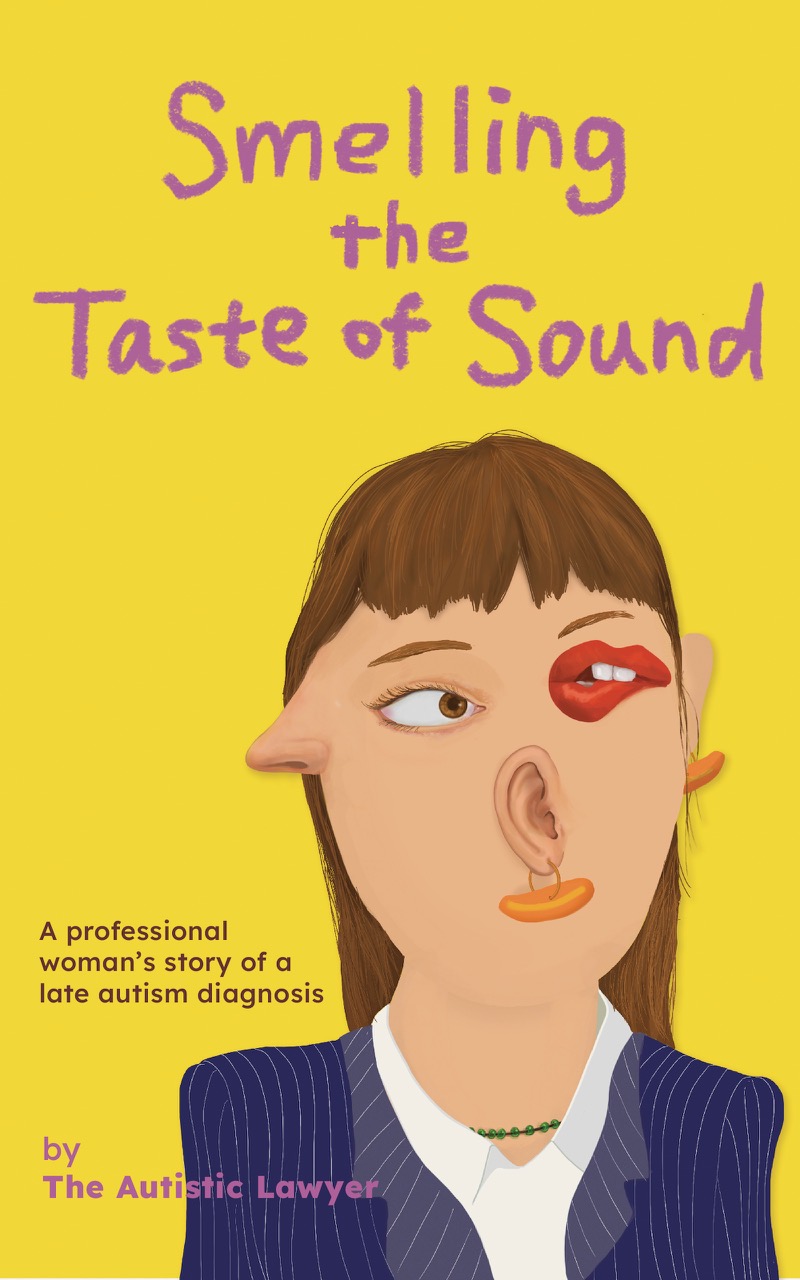

“At age thirty, I decided to pursue a career in law. I left my job in the corporate world to retrain as a solicitor. Three years later, I was diagnosed with several conditions, including autism, ADHD, dyslexia and dyscalculia. I was thirty-three, and it was a Wednesday. Shortly after being diagnosed, I joined a tough, gritty law firm as a trainee solicitor, where much of the work was publicly funded.”

Above are extracts taken from my memoir and set in motion my life from diagnosis, to now.

This is not a story I expected to tell. My upbringing, while not straightforward, would not have indicated that I’d be likely to experience big changes and insights later on in life.

You could call it a triumph over adversity, but I’d just say it was my life after I turned thirty. At the time, I didn’t see it coming, but in hindsight, I should have.

I want my story to show that you can achieve your goals and dreams, not in spite of challenges and invisible disabilities, but because of them. I hope that my account can inspire someone, neurodivergent or otherwise. It’s not the end, but the beginning.

The Autistic Lawyer