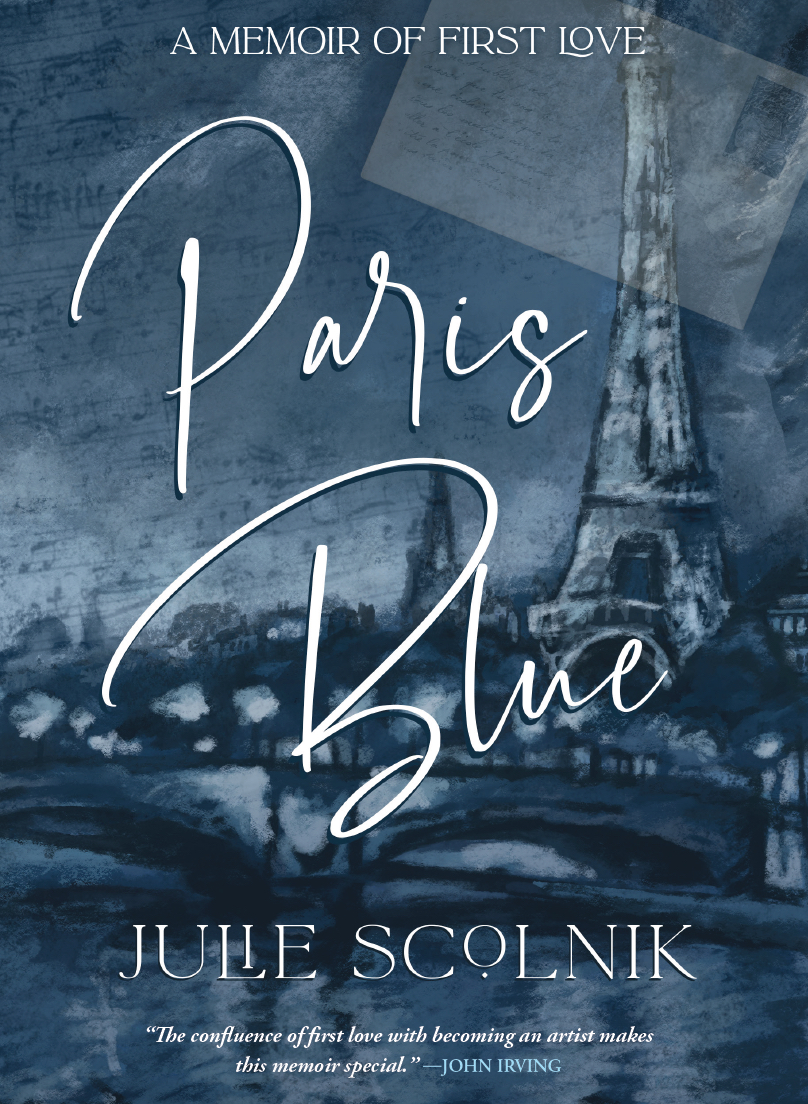

PARIS BLUE, a memoir of first love

Paris. June 1977

Dear Julie,

This letter won’t reach you for days. When it does, I hope that you will have regained your equilibrium. As for me, I am sinking like a ship in a storm. Yesterday after you left, I lived through one of the most difficult days of my life. My body was knotted, as if, at 1:30, when your plane took off, all the existential anguish that you knew how to appease, surprised me again with more force, more tenacity.

Paris seems absurd. Yesterday, so as not to struggle against invincible forces, I drove down both rue Brown-Séquard and rue Bonaparte, willing you to appear. Please send me as much as you can about your life back home. You know where I work and live. But I can only try to imagine you in this vast unknown, and it’s unbearable.

Luc

Paris. September 1976—eight months earlier.

Perched on my toes, I peered over the upright piano and frowned at the fat gold Buddha wedged behind it. My elbow had inadvertently sent it flying while I was unpacking my music and I’d watched its rotund belly sail across the smooth dark wood and disappear with a thud. I wondered if Madame Cammas would even notice it was missing, and considered leaving it there until I left Paris the following June. It wasn’t mine, after all, and I was scheming to decorate my room as I always had since I was ten years old—with pretty things that reminded me of home. Like my twelve Japanese rice paper woodcuts of the calendar months that had migrated from summer music camps to all my dorm rooms at Exeter and Wesleyan, each time animating an entire wall with vibrant color and whimsy. It would only be a matter of time before a cluster of rainbow-colored origami cranes would hover delicately over my bed. But the unexpected discovery of a piano in my own bedroom—even an old out-of-tune upright with antique yellow keys—convinced me that finding this lodging was fortuitous.

A few months earlier, when I was tracking down a room to rent in Paris for my junior year abroad, I was connected through my French Exeter roommate to a museum curator who rented a room each year to a student. A curator! I imagined she’d live in a grandiose limestone building built during the Belle Époque, her apartment filled with records, books, and paintings. What would I wear when she invited me to the opera?

But the day I arrived in Paris, my taxi turned instead onto a tiny, quiet street in the fifteenth arrondissement and stopped in front of 9, rue Brown-Séquard. Not one of the majestic Haussmann buildings I had read about, but charming nonetheless, with a very respectable entrance and characteristic black ironwork balustrades defining the upper floor windows.

I had slid out crisp new francs to pay the taxi driver—bills featuring stunning, colored portraits of Debussy, Berlioz, Cézanne, and Saint- Exupéry—even the money in France was artistic! I hobbled toward the entrance with my heavy bags and rang an oversized black bell. A dour guardienne, who bore an uncanny resemblance to the housekeeper in Rebecca, appeared and grimly indicated Madame Cammas’ ground-floor apartment just inside the foyer to the right. I knocked twice before a stooped, boulder- bosomed elderly lady opened the door. Her wide mouth was turned up in a clownish smile, and layers of thin, crinkly skin draped her eyes. A mass of gray hair was pinned randomly on her head, and a shapeless print dress hung low to her lumpy calves.

“Bonjour Madame Cammas, I am Julie Scolnik,” I said in perfect schoolgirl French. “I hope this isn’t too early for you.” It was eight o’clock. “MAIS NON!” The old lady’s voice was thunderous and unevenly timbered, vaulting from chest voice to falsetto within the same word. “ENTREZ! ENTREZ!” She tried unsuccessfully to pick up my unwieldy suitcase, but managed instead to drag my smaller leather satchel through the entryway without lifting it off the ground. Flustered, she led me down the hallway.

“THIS IS YOUR ROOM!” she bellowed in French, indicating the high-ceilinged bedroom at the end of the hall. I glanced at the piano, fireplace, and armoire.

“It’s perfect. I love it,” I said.

“TANT MIEUX! All the better!” Madame answered loudly enough for the people upstairs to hear. My landlady scurried like a muskrat into an antiquated kitchen, opening the door of her waist-high fridge.

“You can use this shelf for your groceries,” she announced as she pointed to a small empty shelf above one crammed full of tiny yogurts, leftover soups, and plastic-wrapped, fatty, mystery meat.

“When you make a phone call, you put one franc in this black box!” Madame warbled, after leading me into a large somber living room, furnished with dark furniture and an old television in the corner. It was decidedly devoid of books, records, or paintings. She can’t be the curator at a museum, I thought. Maybe she sells the postcards.

“And for ten francs extra a month you can take a bath three times a week,” she added. “Hang your dresses in this armoire in the hall, with mine. You’ll need to buy your own sheets, but you can borrow some from me until you do.”

I tuned in and out as Madame Cammas recited other house rules in a very loud French falsetto. The scratchy sore throat that had incubated on the red eye from Boston was beginning to throb with pain and I desperately wanted to shut my eyes. But I accepted my landlady’s offer to tour my new neighborhood, so out we went, past the local post office, bank, and small épicerie. We stopped at the closest metro stop, Gare Montparnasse, to buy my carte orange, the laminated monthly metro and bus pass to anywhere in Paris. On the way home, a blast of warm air shot up from the subway vents and caught us off guard. We both struggled to keep the world from seeing our bare legs—a hunched, shapeless octogenarian, grinning and embarrassed by the sudden exposure of her vein-mapped calves, and a culture-shocked American college girl in suede clogs and batik wrap-around skirt.

Back in my room, I unpacked my large suitcase, then unlatched the armoire where I placed my clothes in small, folded piles. Tall French windows with shutters looked out onto the quiet street. Here they just call them windows, I thought. I would repeat this to myself quite often, with French bread, French fries, and French braids.

When all my music and belongings had been put away (ignoring the Buddha behind the piano), I leaned into the spotted mirror over the mantel to inspect my agonizing throat and realized, in my miserable state, that nobody was going to take care of me. There would be no one bringing me aspirin in the middle of the night as my mother did when I was a little girl, no warm, soothing broth brought to me by my father. I longed to postpone being an adult for a day or two, just until it didn’t feel as if a knife were slicing through my throat every time I swallowed, just until the inevitable onset of a horrendous cold had passed. I wasn’t savvy and independent like some of the girls at Exeter and Wesleyan who had been riding the New York subway system alone since they were nine. I had never lived in any big city before; I only knew the tame, rolling green campuses of my schools in New Hampshire and Connecticut.

I went through three boxes of French tissues during my first few days in the City of Light, sneezing violently and blowing my nose till it was red and sore. With watery eyes, I stuffed tissues into my pockets and found my way to Galeries Lafayette, the Macy’s of France, to buy sheets and a small radio. Days later when I finally began to recover, I flung my shutters wide open, skipped out of my room, and wandered down to Montparnasse, stopping at a dazzling flower market for two dozen lavender roses. Then all at once, the stunning reality began to sink in: I was twenty years old and living in Paris.

TWO

Dear Julie,

This past weekend I went to the countryside in Anjou. It was sumptuous and magnificent and full of scents. In a beautiful country house, I allowed time to pass, thinking about you, about these months together, while listening to Schubert, interspersed with sounds of nature.

And now I am back in Paris which is too full of memories: the flowers you threw into the Seine on our last day together on June 26, The Red Lion Café, St. Germain, Bus #48. I want you to know how at every moment my life here is hard for me without you. I try to stop thinking about you so that I can work, eat, and sleep, but you always return to me full force by a ridiculous little detail.

One week ago, we went to Versailles. And yesterday, I relived, hour by hour, our separation. I’ll write more tomorrow. Tonight, I’ll just listen to music. The flute will obsess me to my core.

Luc

Being on my own in a city as intrinsically poetic as Paris proved a heady mix for a small-town Maine girl like myself. At first, I floated through the streets during the calm morning hours in a blurry state of disbelief, light-headed from bus fumes that mingled with the intoxicating aroma of warm croissants wafting from the boulangeries.

“Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,” so the poem says.

Two years into an undergraduate degree in a bland Connecticut town, I longed to gather mine. And why not in Europe, which I had craved ever since spending a few weeks in the South of France at nineteen, playing in the masterclasses of world-famous flutists. Now I was to study privately in Paris with one of my teachers from that summer.

Each day I strolled down the wide airy sidewalks of Boulevard du Montparnasse to reach my classes on a small side street, rue de Chevreuse. Morning was my favorite time to sit in the grand cafés, with early golden light slanting across my round, marble table. It wasn’t long before I felt like a regular at Le Dôme and La Rotonde, two of the iconic ones along the way.

My confidence grew with my daily routines, as I sauntered each morning over to my habitual corner and ordered a big café au lait. It always arrived with two paper-wrapped sugar cubes, tiny luxuries next to the pedestrian packets of loose sugar served in the U.S. Even though I never took sugar in my coffee, the minuscule etchings of Parisian churches and calligraphic letters on them enticed me to reach for one now and then. I couldn’t help thinking about and imitating my Russian immigrant grandfather, whom I had watched countless times bite off half a sugar cube, hold it in front of his mouth, and take sip after sip of coffee through it, until it had completely dissolved on his tongue.

Exuding self-importance in these cafés was crucial if I wanted to command respect in the subtle power struggle with the waiters. I knew that the slim, black-vested servers weaving gracefully between tables could ignore me endlessly if they deemed me unworthy of their attention. So I prudently ordered in a manner that wouldn’t peg me as an American. Never a café au lait but a grand crème, never an espresso but a petit noir. If I ordered my coffee that way, there would be no odd look in the waiter’s

face that registered une étrangère (a foreigner), no split second of hesitation before hearing, “Très bien, mademoiselle, tout de suite.”

When I stopped in one of the cafés after class in the late afternoon, it was brimming with regular patrons. I began to recognize certain types— elderly French ladies sitting shoulder to shoulder looking out onto the street, their miniature terriers perched on chairs beside them; businessmen in suits nursing tall beers; students smoking cigarettes and writing notes at their espresso-cluttered tables; graying, long-haired intellectuals with scarves, looking important, retired, and committed to café life as a means of keeping the old political discussions alive over their plats du jour.

I walked for hours, sometimes entire days, until my calves ached and my feet pulsed with pain. The breathtaking splendor around me created a bottomless pit of yearning that made it impossible to choose in which direction to wander—along the quais past the dark green kiosks of old books, prints, and maps, the Seine glittery from the early morning sun; or down the cobbled streets of the Latin quarter, past picturesque squares and fountains like Place de la Contrescarpe. I couldn’t get over the intense thrill of instantly becoming part of any Paris scene I chose, as if I had just waltzed into a French film or painting. For the first three months I had only one thought: why would anyone live anywhere else if they could live in Paris?