Approx. 91k words

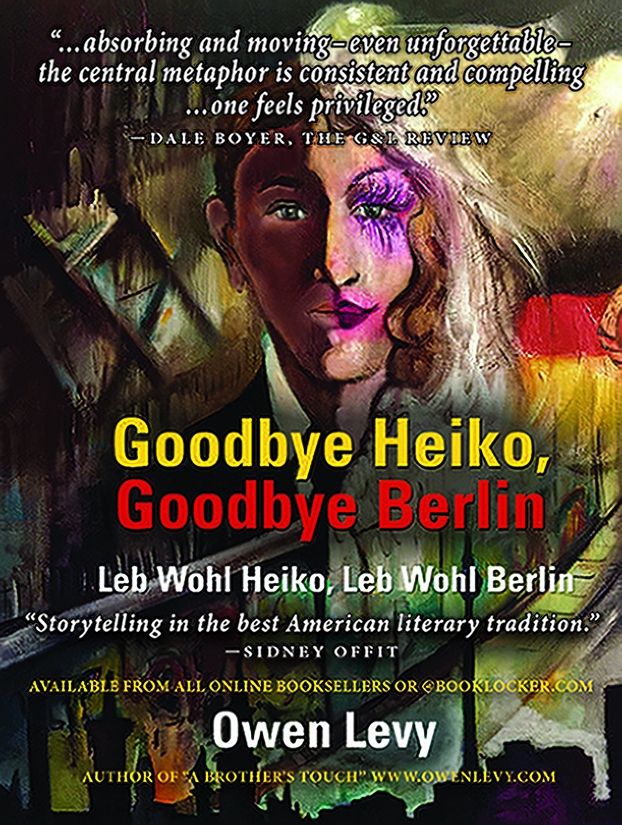

GOODBYE HEIKO GOODBYE BERLIN

A Novel by

Owen Levy

Epigram

A TELLING FORETOLD

Christopher Isherwood (1904-1986)

“Comparing the two cities—the Berlin I knew in the early thirties and the [divided] Berlin I revisited in the early fifties—I have to admit that the latter is, in many respects, a far more exciting setting for a novel or sequence of stories…

“All that is not for me to say. The ways of my own life have led me elsewhere. But I hope some young foreigner has fallen in love with this later city, and is writing what happened or might have happened to him here.”

“The Berlin Stories” Preface (1954)

RUMINATIONS

(italics)

How trustworthy is memory? Is what is remembered really what happened? With the passing of time comes embellishment and omission. Is what we see or think we see a reliable record? A recent incident precipitated a wistful glance back.

My first thought was ‘I saw a ghost!’

Had I?

I strained to get a better look.

It was he! I was almost certain.

Then again, maybe not.

Blame it on optical wish fulfillment: conjuring up what I want to see based on vague semblances—sloping shoulders, wind-whipped locks of hair, the distinctive stride of his ‘don’t-give-a-damn swagger’ that drew me to him in the first place.

It just could be possible, I kept telling myself. It just could be he.

What if it wasn’t he? No big deal! I have been mistaken before.

Still, I had to be sure—sure that my aging eyes were playing tricks and it was not at all whom I thought it was.

Then again what if it was—what if Heiko was back in Berlin? The prospect made me giddy.

Naturally, the sighting was inopportune. Routine tasks needing attention occupied my thoughts. I was riding the Berlin subway. After nearly three decades of interruption, regular train service once again freely crisscrosses the reunited city.

Suddenly daylight flooded the car as the train burst from the gloomy tunnel ascending elevated tracks. Century-old tenements rushed past, many spruced-up with modish paint jobs and crowned with glistening glass and chrome cupolas—like grand dames of a certain age gussied up in stylish garments and trendy hairdos.

Casually glancing out the window at shoppers crowding the sidewalks below was when I saw him—or thought I saw him!—dashing into an ‘Adults Only’ video store! I pressed closer to the glass for a better view but he was up the single step, across the threshold and through frosted-glass doors in a blink, no doubt minimizing exposure to passersby.

Though the glimpse was fleeting, the resemblance was remarkable; so much so, I got off at the next stop and hurried back to the location by foot to investigate.

I had yet to patronize this particular purveyor of adult erotica, so now I had an excuse. With so many new businesses popping up along the one-time seedy Schönhauser Allee, staying current was getting harder.

A sign posted at the entry announced Kinotag or Discount Movie Day. I gave the cashier ten euros and got back change—a few euros saved if I were not mistaken! Buzzed into the arcade’s shadowy backrooms, I recognized the all too familiar layout: a maze of dimly lit passageways, private viewing cabinets, and pitch-black cul-de-sacs.

Raw techno beats—mercifully subdued—pulsed through overhead speakers. Determined to make connections, patrons of diverse ages and proclivities lurked about, sizing each other up. The place was popular enough—or at least on this particular afternoon—perhaps owing to the reduced cost of dalliance.

Making a brisk sweep through narrow intersecting corridors, I feared my phantom was settling into a booth and, as some cruisers are wont to do, would pass the next hours encamped and engorged, stimulated by hardcore video images while simultaneously hosting all comers through ‘glory’ holes strategically cut in the common wall to adjoining stalls.

I checked the WC and adjacent beverages vending machine area. No sign of the apparition glimpsed from elevated tracks. Who knows how long it might take our paths to cross, especially with so many horned steeds rutting about to keep him distracted.

Patronizing such places was a bit out of character for Heiko, when I gave it some thought. He never seemed that interested in sex to begin with and was never very promiscuous. Of course, we change over the years and so do appetites. Perhaps middle age found him more comfortable with his sexuality. From the hubbub going on all around me, he was not alone.

Up and down cubicle rows, I wandered. Some users kept their doors ajar, one eye sizing up prospects, the other taking in lusty on-screen antics. Quite a few closed doors left to the imagination what transpired out of sight. He could be behind any one of them.

What if I was wrong? Once more doubt set in. What if it was not my old pal but somebody else, somebody resembling him: a doppelganger? That would not be surprising either. Not the first time I hit a brick wall looking for Heiko. Fact is, I had pretty much given up on finding him, but here I was once again clinging to the slenderest of threads.

I positioned myself at what looked to be a central vantage point. Give it an hour, not more, I told myself, my original errands long forgotten.

Meanwhile I had no interest in “connecting” or even amusing myself for that matter. I was firm but polite when overtures were insinuated, indicating with a shrug that I was pursuing a different kind of tale.

That was true. Anticipating an encounter with Heiko after so many years was daunting, exposing conflicting emotions I had not yet fully come to terms with. I was managing to get on quite nicely, not knowing for sure where he was or what he was doing.

Yet, on this particularly cold clear wintry day, he once again took center stage in my ongoing interior monologue. Yet, like anything you want too much and ultimately never fully attain, selective memory has its own seductive appeal.

Time passed with no sightings. I was beginning to worry he might have made a quick purchase—toy, video, lube—and left in the time it took me to backtrack.

It was beyond frustrating yet consoling to know that some patrons are wont to stay out of sight, lost in these labyrinths of lust for hours on end. Then suddenly emerge, vaguely disoriented, adjusting garments, heading toward the exit.

Not so many years ago, I periodically whiled away hours in such places. Now I just wanted to see if it were Heiko or not Heiko. Even in reluctant memories, my old Ossi comrade commands full allegiance.

I was about to call it quits when, finally, the object of my pursuit emerged through the door of a shadowy video cabinet. He moved briskly away down the dim corridor. I followed, heart racing.

The murky lighting and the awkward perspective made partial facial features hard to distinguish. The height was right though, and so was the hair texture: that thatch of thick tangled locks he was forever cutting and styling, streaking and frosting.

I wanted to call out his name but held back, fearful that if it were Heiko, he would not have appreciated so artless a singling-out.

Maneuvering around a partition, I attempted to meet him head-on. When I got to the other side, he was gone! Somehow, during the brief time-lapse he slipped out of sight, perhaps going into yet another video booth.

I was intrigued more than ever, even while convincing myself I had to be mistaken. It couldn’t possibly be he. How could it be? How could he be resurfacing all these years later? Maybe he never really left Berlin. Then again, why did he have to live in Berlin anyway?

He could be living in Brandenburg, Hamburg, or some other German ’burg. Anywhere! Abroad! Paris for that matter! So maybe he’s here on a visit. Still, how does one substantially disappear without trace in the age of DNA and electronic paper trails?

Yet, that is how it appeared: Heiko had simply vanished.

(Italics end)

SEDUCTION

In the mind’s eye, snapshots of cherished moments crystallize and become iconic: tableaux vivant minutely etched in memory. That’s how it is with Heiko.

Memory easily recaptures the first time he entered my consciousness: blithely striding into a crowded café near Alexanderplatz. Animated in lively discourse with two mates, yet clearly keeping an eye open for places to sit.

Perhaps it was the flowing locks, glowing complexion and long vintage military overcoat draped dramatically across his shoulders. In that first glimpse, he was luminous. Natural and charismatic, oblivious to impressions he made, or so it seemed.

That was my maiden trip to infamous East Germany, the first of many visits as it turned out. It was years before the infamous Berlin Wall would come down. I arrived days before in what world press had long dubbed “The Divided City.” It was my first trip to Europe.

The oppressive Cold War fortification was solidly in place. Lives were still being lost in attempts to breach it. I found the city’s parallel histories fascinating. It made me eager to get on the inside and embrace the romance that had drawn so many others before me.

To know truly a foreign country, understanding the language seemed imperative. To that end, I took a crash conversation course in German only to discover that most people I eventually encountered spoke better English then I did Deutsch.

The first days wandering West Berlin were haphazard with no particular plan. What struck me was how Americanized the city looked and felt. Sartorial styles, international-brand advertising, fast food restaurants were all too familiar.

Ironically the two meat dishes American food culture embraces had origins here—frankfurters and hamburgers, and particularly notable because not only are the names adopted from German cities of origin but, essentially, the forms—sausage or wurst and meat patty or boulette, as the lumps of ground meat are dubbed locally.

Both served with a roll or bun making them convenient takeaway. Classic German Street fare regurgitated for US consumption, now repackaged, and reintroduced to the Fatherland by Mickey D and The Burger King. The budget bites had come full circle.

The woman who managed the pension where I was staying told me to definitely visit the Empress Sophie-Charlotte’s Summer Palace, and in a museum nearby, see the celebrated bust of Egypt’s legendary ruler Nefertiti.

I hit the museum first and was startled to discover a grave robber’s trove of impressive artifacts and antiquities displayed along with the Nile queen’s iconic headdress, but most alarming was seeing the actual Gates from the ancient City of Babylon! How in the heck did they get those? I wondered aloud.

Instead of touring the massive stone pile where German monarchs once summered, I opted to wander the expansive garden out back. There were others taking brisk strolls and one or two joggers.

The grounds looked neglected and the plantings probably not as elaborate as they once were. Certainly, nowhere near the lavishness of Versailles but more than adequate for a seasonal royal residence.

My energy ebbed as daylight dwindled into dusk. I found myself yawning. Still jet lagging, I headed back to my room to grab a nap.

Hurling my weary body onto the fluffy duvet and big soft pillows of the rented bed was unanticipated luxury. At modest prices, too. Once comfortably positioned, I easily drifted off . . . but woke with a start.

For a moment not sure where I was. Enveloped in inky darkness I groped around for a lamp switch. Whatever I was dreaming was gone leaving no trace. Yet it gave me an unsettled feeling—and sudden pangs of hunger. I had barely eaten all day.

I jumped out of bed, pulled on shoes, and went outside looking for something to eat. At the nearest street corner snack wagon, I gobbled down bland currywurst sausages and oily French fries, chased with local brew.

The night air was damp, chilly even. Seduced by the Ku’Damm’s glittering display of luxury goods and services I drifted up the broad thoroughfare idly window-shopping.

It was late and traffic was light. Several strikingly attractive young women lingered in doorways or leisurely strolled curbside. They were stylishly dressed and wholesome looking. Slowly it hit me they were “working girls” discreetly offering themselves to potential clients in passing vehicles.

The women gave me hardly a second glance, street-savvy enough to recognize my orientation, I imagined. Here indisputably was a commercial street tendering to the full spectrum of consumer goods!

Before leaving the States, I collected from various friends and acquaintances phone numbers for three, possibly four, local contacts. As it turned out, the first I tried had moved away—or at least the line was no longer in service if I understood the German message correctly. “Kein Anschluss unter dieser Nummer!”

Listed next was Holger. He was the one-time romantic partner of Lorenzo, someone I knew hardly at all. Lorenzo was a genial Venezuelan of Italian ancestry who hit on me one night in a crowded Westside bar. I mentioned my upcoming trip to Berlin.

He boasted of living there the year before, assured me I was definitely going to like it. He suggested I look up his former lover.

“Holger Bambeck,” chimed a melodious baritone on the second ring.

In halting German, I introduced myself and explained how I got the number. The voice on the other end quickly pooh-poohed my awkward phrasing.

“Don’t stress out,” he said. “I speak English.”

His tone was matter-of-fact, not at all condescending.

“I’m never going to get any practice if everybody speaks English!” I pouted.

I mentioned the Lorenzo connection prompting the call.

“Lorenzo!” he gasped giddily. “Where did you see Lorenzo?”

“He’s living in New York.”

“Really?” He sounded surprised. “I thought he went back to Caracas. Who can keep up with that sexy empanada?”

“I have a feeling you did,” I kidded.

“Well we’ll just have to compare notes,” he retorted coyly. “Where are you staying?”

I told him the name of the pension.

“You’re practically in the neighborhood. Come over for coffee now if you want,” he gamely suggested. “I’m off today.”

“I’d love to.”

He told me how to find his place on foot. His directions easily followed. When the ornately carved door of his flat swung open, a great bear of a man greeted me with playful hug and double cheek brushes.

Stepping back to look me over, he smiled and shook his head approvingly.

“With your beautiful skin and big brown eyes you are going to have lots of fun in Berlin,” he assured me.

He led me down a long corridor into a bright spacious kitchen flooded with afternoon daylight.

“This place is huge,” I gushed.

“Yes” he said, “These flats from the Kaiser’s time are wonderful but expensive to maintain.”

While fresh coffee filtered into a clear flask, he arranged packaged cookies—the kind thoughtful hosts keep on-hand for unexpected guests—on a colorful plate.

Picking up the coffee pot, he told me to grab two mugs from an open shelf. We settled at one end of the long dining table. He poured. The coffee was stronger than my usual brew. I added more milk.

“So what’s Lorenzo up to these days—that mad Latin stud?”

“Well, last time I saw him, actually the only time I saw him: he was doing great, a very agreeable guy.”

“South Americans are good company; and so good in other ways,” he beamed. “Did you and he get acquainted?” no mistaking the inference.

“Technically, no, we never got that far,” I sheepishly confessed.

“Well, you missed out. We had great times when he lived in Berlin. Let’s just say he has natural gifts—and he keeps on giving!” Holger gushed.

While we chatted, Holger’s flat mates floated in and out, some saying hello, others completely ignoring us. He explained that this was a ‘WeGe’ or ‘wohngemeinschaft,’ a cooperative living arrangement as it were. He shared household costs and chores with five others.

“Two lesbians, two other gay guys, Yolanda—she’s transitioning—and I make six,” he tallied. “It’s much better than living alone. I could never afford a flat like this on my own.”

To pay his share he jobbed as a home health attendant for housebound retirees, quickly adding, “My real love is music. Weekends I lay down tracks at dance clubs around town. You come hear me work my magic sometime.”

“Yeah, definitely, I’m open for anything.”

“I can put you on the guest list,” he offered.

“In Berlin, do as the Berliners do! Put me down.”

“So you’re a photographer, I believe you mentioned?” he asked somewhat awkwardly.

“Not exactly, I do photo research and archiving.”

“Sounds like a great job: sitting around all day looking at pictures.”

“Well, I like to think it’s a little more complicated than that, but basically you’re right!” I conceded. “Some days I can literally slog through thousands of images looking for the right ones.”

“Well, you came to the right place. Germany is full of picture archives. You think you might stay and work here for a while?”

“Who knows, I haven’t given it much thought yet. Anything’s possible.”

“It’s easy to get flats. Rents are cheap. Checkout Kreuzberg, it’s sort of our East Village. Factory spaces converted to studios. Used to be mostly Turkish guest worker families, but artists and musicians are moving in. There’s even a cruisy café to check out the local action. If you stay longer you might want to get a place.”

“At the moment I have no plans other than a visit,” I assured him.

The next day I followed Holger’s lead and took my first Berlin subway ride to visit Kreuzberg. The rundown tenements and former commercial buildings certainly had scruffy charm to match any gentrifying Manhattan neighborhood. Rather than Hispanics, swarthy, hairy, heavily bearded Turks set the ethnic flavor. They created a Little Ankara with thriving businesses offering the specialties and services of their homeland. Heavily veiled women in traditional burkas were common sights.