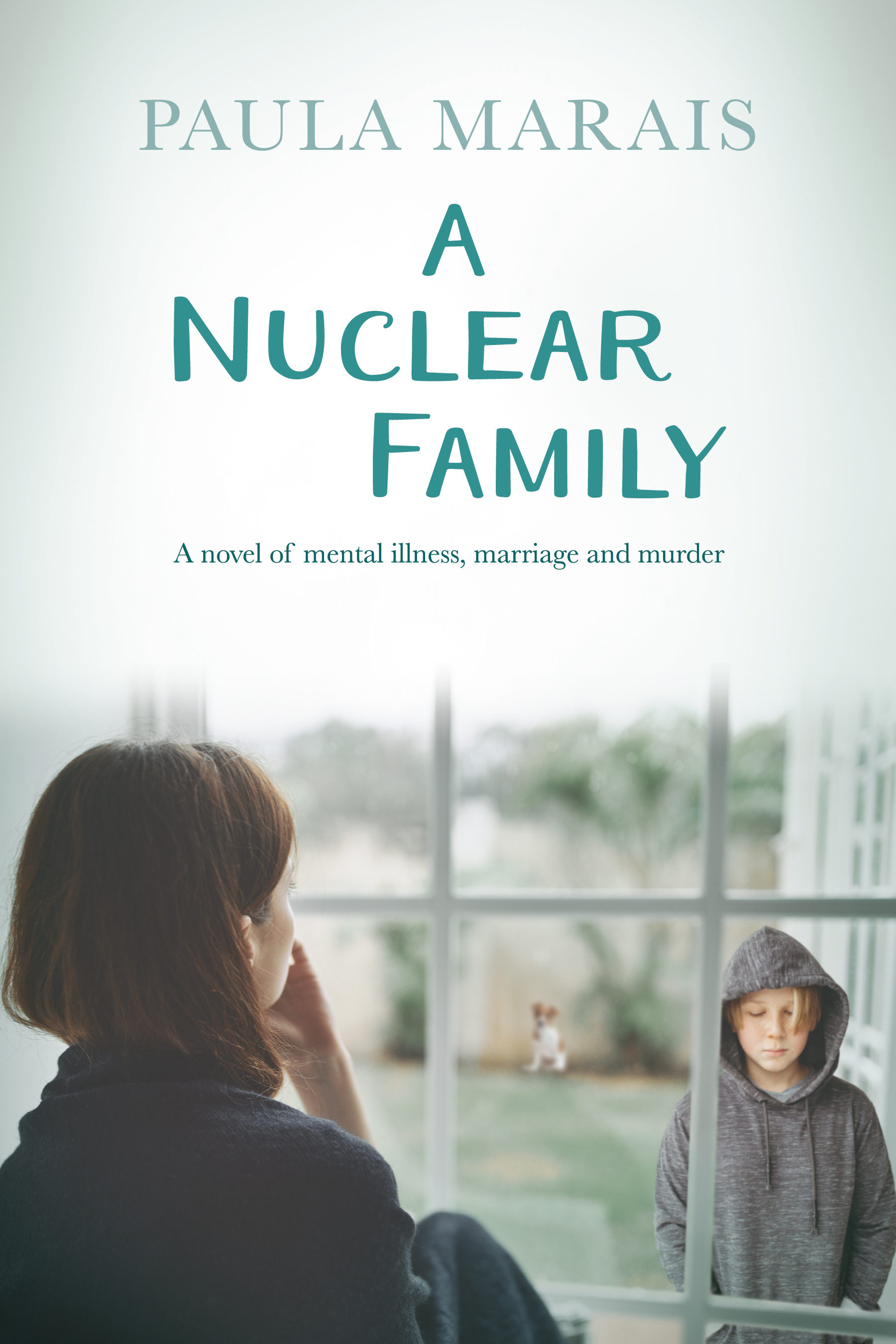

A Nuclear Family

PART I

ALICE

What would I do without you?

Five minutes later would have been too late. Thank God for her forgotten laptop on the dining room table. And the fact she’d realised she’d left it there and turned her car around. Dropping her keys on the kitchen counter, she saw his schoolbag hanging neatly on his ‘Albert’ hook. Alice felt an unexpected feeling of disquiet creeping into her gut. Why was he still here?

‘Bert?’ she called.

There was no reply and she wondered, not for the first time, how well she actually knew her child. To think he’d bunk school, knowing for sure that she wouldn’t have noticed, made her blood boil. But it just wasn’t like him, which made her feel suddenly more anxious than irate.

‘Albert!’ she called.

No reply.

She marched down the passageway to his bedroom; the door was tightly shut, and when she pushed it, found that it was locked from the inside. She beat hard on the door.

Bang! Bang!

No reply.

Albert was an unusual boy, but he was generally more defiant that disobedient. Until today, of course: missing school.

Alice banged one more time and when she again got no response, exited the house to peer in through Albert’s window. And it was then that she saw him, his prepubescent body hanging from the light fitting by his scrawny neck. His eyes bulging. A rope of sorts – perhaps the belt of a dressing gown – holding him. Alice screamed. If she had not heard herself, she would not have believed a scream like that could come from her. But it also pushed a huge surge of adrenaline into her body. When the window pane tumbled before her like a jagged waterfall, she barely noticed the shards of glass burying themselves into her flesh. She tossed the garden chair she’d seized to shatter the window, her feet light upon her crystal carpet.

She couldn’t reach his neck. But she did register where Albert’s scratching fingers had tried to untie the tightening noose. And so she held him, lifting his whole body to ease the pressure where the life had begun to leave him.

‘I’ve got you,’ she said. But how to free him without letting him go? She needed help. Then she glanced around frantically and realised the stool where Albert had been standing was lying at his feet.

‘I’m going to have to release you,’ Alice told her son. ‘Just for a second.’ He shook his head wildly. ‘I need to cut you loose.’ But it was less than a second and his feet were back on the stool that had set him swinging. Alice saw Albert’s nail clippers lying next to his bed and used these to hack at the noose. It may have taken only a few moments, but it felt like hours. Shredded material nicked and ripped to reveal a neck ringed by a welt of crimson. He had a pulse, thank God, and he was breathing. She placed her child on the bed, her own breath echoing in her head. ‘I’m calling an ambulance,’ she told him. ‘But I’m coming back. I love you.’

And when the siren finally wailed increasingly loudly as it came down the road, it was the sweetest sound she’d ever heard.

***

In the beginning, or the beginning of them as a family, Alice had had certain expectations. Bruce was going to be a wonderful father. People liked him. He was sporty. He loved kids. He enjoyed team games. Unfortunately she had not realised that a love for the outdoors and certain qualities of extroversion did not necessarily make a good dad. From the moment Albert was born, Bruce complained about the lack of sleep. He moved immediately into the spare room, leaving her with her little bundle who howled most of the night. Had she had another child to compare Albert to, she might have thought the overly active baby was unusual. But she did not. Because she was inexperienced, she also did not realise that the way Albert spoke full sentences by seven months and could recite all the capitals across the globe by three and a half was not mere fluke. Albert was a challenge. Lithe and energetic, he was hard to exhaust. Bruce thought himself remarkably clever to teach Albert how to turn on the remote for the television and tune into CBeebies. That way, when the little mite exited his bed at five in the morning, he could entertain himself for hours and they got to lie in. Except that what Bruce wanted to do in that time was not what Alice was after. He wanted wild, passionate bonking and equally passionate kissing (preferably with raunchy commentary in between). She wanted an uninterrupted sleep. They fought about it more than she cared to admit. It felt to her that where Albert ended Bruce began and she was left with nothing of herself. When, for instance, had she last read a full book? Or sat on the loo without either Bruce or Albert walking in? At least Bruce didn’t expect to sit in her lap, but she wouldn’t put it past him. It was like living with two toddlers, not one. How was it then that two years later, they would find themselves adopting? It wasn’t that she ever wished she could send Enjoy back, especially after the tragedies the poor girl had suffered. It’s just that, well, Alice was further reduced. And then the dog. A Jack Russell, Malawi, with short legs and a bad temper, that dug up her garden and howled if there was thunder, which didn’t happen often, that was true. But still …

She didn’t have much time to think about her choices but when she did, Alice thought that perhaps she’d settled too young. Too inexperienced. Despite being a competent draftsman (draftsperson?), she wished she had studied further, not followed her future husband across the country where he did his postgraduate studies in electrical engineering. And then, of course, his scholarship to the US, where she was not allowed to work and so spent much of her time doing various courses on the internet, which added up to something but nothing (interior decorating; fabric design; furniture restoration; paint effects; découpage). And it wasn’t that she didn’t enjoy their time in the States. They’d considered living there, after all, and not coming back. But the thought of raising a family without a support network had drawn them home − that and the consulting position Bruce had secured in green energy, which wasn’t even the rage then. But now, now Bruce’s company was doing so well “people were throwing their credit cards at him”, as he so tactfully put it. Their house was already completely off the grid. Why give those corrupting bastards a chance to have a hold on us − which was especially useful, as the dam levels sank lower and lower and people were flushing their toilets with buckets of grey water saved from the bath (while their own grey-water system had been doing this automatically for several years). From anybody’s viewpoint, they had a good life. They hadn’t lost parents yet, although hers were far away living in Edinburgh (so much for family support), and his mother, Janet, now remarried to a professor of audiology, spent a great deal of time travelling with him to medical conferences. A retired tour operator, she had very little interest in being at home, or spending time with their children. The message was clear. She’d done her time and it had been a burden. As soon as Bruce and his brother were out of the house, she’d dumped their father – a quickie divorce, during which she pretty much gave him everything and told him not to contact her – and went to teach English in Japan. The TEFL course she’d been doing had been a preparation for this exit. Bruce’s father, an unassuming and rather grey financial director of an insurance firm, had not seen any of it coming. Janet had always been moody, even flighty. Prone to giddy excitement and wallowing self-pity. But it appeared, this time, that things were different. Bruce and his brother Gabriel had been left to pick up the shattered pieces of their wrecked family, while their mother cheerfully waved from the airport, blowing enthusiastic kisses as she went through customs. That first exit, she’d apparently not returned for two years; not even for Christmas.

It was not really surprising, then, that neither Bruce nor Gabriel wanted their mother, or her new husband, around. Though Alice did not know them very well, and didn’t particularly like Janet, she did like Janet’s husband with his booming laugh, affable manner and ability to speak to children. Bruce’s father, Albert, after whom their son was named according to tradition, had only become greyer, working long hours, drinking expensive wine before bed (a bottle a night, on average) and very occasionally dating women much younger than him. Albert (senior) infrequently invited them to Kelvin Grove for Sunday lunch and a game of tennis. It wasn’t a completely dispiriting affair. Albert also attempted levity, but his in-between-relationship loneliness was almost palpable and made Alice pity him. When he looked at her across the table, she sometimes had a sense of looking at her own husband twenty years on, which gave her a disheartening sense of foreboding. Would she make Bruce that unhappy too? It wasn’t as if she was about to jump on a plane and leave her family behind, but when she thought about it, she could almost understand Janet’s actions. Not, of course, that she’d ever admit it. Freedom was something she’d never really experienced. She’d met Bruce very young, at fifteen, at a swimming gala, where she was serving hotdogs to raise money for the SPCA. He was already in Matric, captain of the swimming team and insatiably hungry. After the fifth hotdog, which he’d bought shirtless, dazzling her with his tanned chest and manly arms, she was already smitten. Bruce had helped her carry the trestle table to her mother’s car, lifting it in with one hand while he grinned at her. In those first moments of their meeting, she’d hoped he’d ask for more than her name, but he hadn’t. Nevertheless, she knew where he went to school and made it her business to attend every gala after that. She was gratified, at least, that when he saw her again, he remembered her name. It was a sweet meeting, as she recalled it, and he touched her shoulder, a moment she can still recall with such clarity that she wonders now if perhaps it had become more in her head than it actually ever was. The jolt to her shoulder. The smile. His casual mention of a movie, if she was interested. It was called Dances with Wolves and there was a crowd of kids. It wasn’t a date, as such, but she’d dressed and prepared for it like it was. Her mother dropped her at Cavendish and walked with her to the cinema.

‘I’m fine, Mom,’ she’d said, trying to slip away with as little fuss as possible.

‘I’d like to see who you’re going to be with,’ her mother said, the Scottish burr still obvious after twenty years in South Africa.

When Bruce appeared from the ticket booth, he walked casually over to her. ‘I bought all the tickets,’ he said. ‘So we could sit together. Hello, Mrs Macdonald.’

Alice’s mother smiled. ‘What time, darling?’

And when she’d left, Bruce tapped on Alice’s arm. ‘Follow me, the other guys are there already.’

She followed him nervously. Going to a girls-only school had transformed boys into strange unknowable beings. Her little brother Jake didn’t count. But Bruce’s friends weren’t only boys, and a few of the girls she knew by sight. They nodded at each other. It wasn’t nearly as intimidating as she expected it would be. When the lights turned off and the music started, she was almost relaxed. Bruce was next to her, holding a huge carton of popcorn, which crunched grittily between his teeth. On the other side was a boy whose name she did not know but later learnt was Bruce’s best friend Oliver. (Later he would be called Martini in some weird corruption of Oliver to Olive to the drink – men’s nicknames were strange.) It was hard to concentrate, however, knowing that Bruce was sitting next to her, and being a person who usually filled empty air with chatter, she found her own silence unnerving. When Bruce offered her some popcorn, she took it gratefully, appreciating the distraction of the cracking kernels. Later, she would remember very little about the movie. The Civil War, some Indians (Native Americans?), beautiful scenery, a love story. Mainly it was the first time that Bruce slipped his hand into hers, squeezing it so gently that she almost wondered if it was really happening. And when the movie finished and he let her go, she thought she might have imagined it, that, except for the gentle heat from her palms. They went afterwards to the Spur and drank cream soda floats. They were sweet and filling, and she wished she was sharing hers because it was just too much for her. She wondered if she would look like a killjoy if she didn’t finish it. The conversation flowed around her and she knew she was quiet. How was she supposed to make an impression on Bruce when she couldn’t even speak? And why could she think of nothing useful to say? She spooned ice cream from the float into her mouth. The saccharinity was cloying. She needed to pee, and how was she going to get past all these people she didn’t know when she was sitting at the end of the bench? Shifting a little, she glanced at Bruce but he seemed oblivious, laughing with his friends about some prank they’d pulled at school. Something to do with marbles that she didn’t think all that hilarious. She took a decision. Nothing of any use to her was going to happen at this table. It was enough for one night. She was making no impression on anyone in this state, and she didn’t foresee that changing soon.

She patted Bruce on the arm.

‘I’m sorry, but I have to go,’ she said softly when he turned to her.

He blanched. ‘Hey, it’s still early.’

‘I know but–’ The fact was she couldn’t think of an excuse. She was bored? Left out? Hoping for something more than this cluster of inane chatter? Needing more attention? She picked up her handbag. ‘Sorry, guys, I need to slide along. Won’t disturb you for long.’

Bruce stood up quickly. ‘Seriously? Let me walk you at least.’

One of the girls in the group glared at Alice, making her feel vaguely powerful.

‘You sure?’

He nodded.

‘Let me just dash to the loo.’ She hated how that sounded, but the truth was, she was fairly desperate.

When she exited the ladies, Bruce was already waiting at the entrance to the Spur. He looked caught off guard.

‘Not your vibe?’ he said idly.

‘It’s not that.’

‘No?’

‘I’m just a bit shy. Not good in … crowds.’ She thought how pathetic she sounded. If she wanted to put Bruce off, she was certainly doing a good job.

But he seemed unperturbed. ‘So, if I were to say, let’s go and sit somewhere on our own, you might be keen?’

She smiled at him. ‘I think your friends will miss you. Candice, was that her name, was already giving me daggers.’

‘Cands does that with everyone she doesn’t know. A bit, well, protective.’

‘She likes you.’

He shrugged. ‘Just friends, Alice.’

***

Bruce was her first and only. She suspected, when she was feeling morose, that she was not his first and only. His first perhaps, but not the latter. It was the comments he sometimes made. ‘I didn’t sleep with her,’ when referring to an ex, when Alice was supposed to have been the only person he’d had sex with. It had certainly been true when they first crossed that threshold. If this was worth saying, then there had to be a reason to say it. Defending the indefensible. After all, they’d been together since that movie night. No break-ups, no drama. They’d even survived the long-distance year when he had been studying in Bloemfontein. She’d been at UCT, in her first years of architecture. And then the sudden move to the US, giving up her own career for a life with Bruce. Did she regret it? Occasionally. She felt like she’d merged her life with his without giving real thought to what she actually wanted. She felt she was somehow worth more than what she amounted to. A mother. A wife. An interior decorator/draftsperson. A daughter and daughter-in-law. A sister. And her family, it turned out, was not what she’d hoped for. For one thing, her own childhood had been stress-free, loving parents in a loving marriage. Financial stability. An older sister, Claire, who was a bit wild, but settled eventually (the dramas later were irrelevant; Alice wasn’t living at home anymore). Jake, her little brother. The problem was that she and Bruce had different perspectives on just about everything. Discipline: she was lenient; he was dictatorial. Money: she was casual; he was miserly. Sex: she was restrained; he was uninhibited. Children: she gave too much; he gave too little. Time: she had none of her own; he protected his, doing whatever he wanted, whenever he wanted. The only thing that seemed to align for them was their love for each other. So while they disagreed, there was always that one inevitable truth − whatever happened, it was them against the world. Well, that is certainly what she thought, until Albert tipped the world off its axis.

***