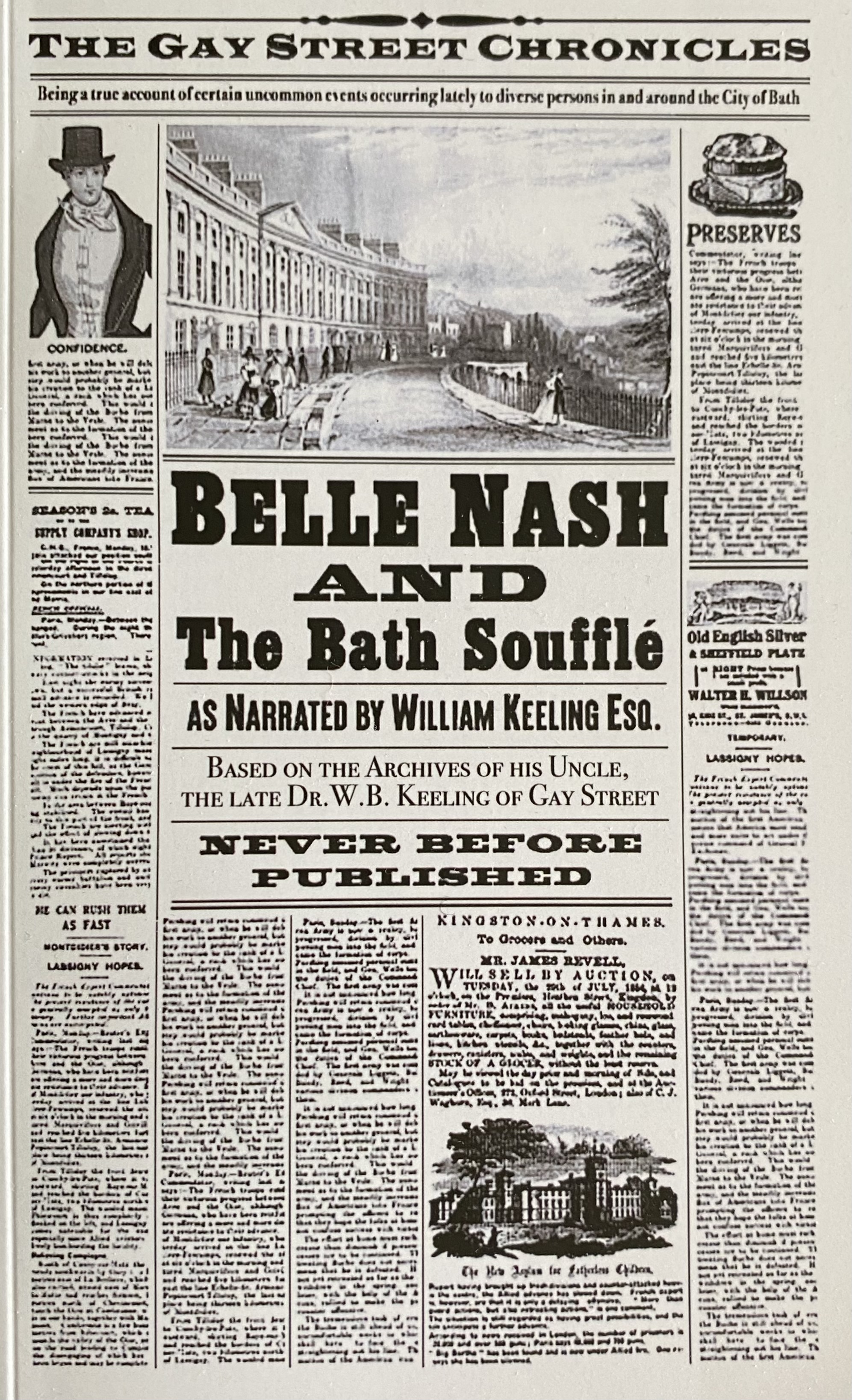

Belle Nash and the Bath Souffle

A true tale of how a sunken soufflé came to reveal a festering quagmire of corruption and bigotry in genteel Bath in 1831. Mr Belle Nash of Gay Street, bachelor and dandy extraordinaire, joins forces with a bevy of disgruntled ladies to campaign for justice. Killer crumpets, a political kidnapping, and a royal intervention from Princess Victoria follow – and what started out as a culinary catastrophe quickly becomes a matter of life and death.

THE ROYAL CITY OF BATH, 1831

PACKING AWAY a dead man’s clothes is never a joyous task, the worse when the man concerned was the husband whom you loved. But a year had passed since Hercules Champion had died and his widow Gaia felt in her heart that the time had come to recognise the past tense and say goodbye if not to the memory of the man then to his garments.

The decision was made in the knowledge that this is what her husband Hercules — rationalist, lawyer and businessman — would have desired. Abiding by her late companion’s will one last time was small comfort, though Gaia Champion too was unsentimental in nature. To delay the task would only have been to sustain unnaturally Hercules’s presence in the house.

She did, however, feel anger at his death. Hercules and the happiness they had shared had been cruelly taken from her by cholera. The epidemic in England had been indiscriminate, felling rich and poor, saints and sinners, alike.

‘The Church would have us believe that there is a benevolent God,’ Gaia said to her young maid Mary as she passed over a shirt to be packed away. ‘But in that case, either God is as indolent as the men He created or in full-blown retreat from the Devil below.’

The maid was an uncomplicated girl, better suited to lighter topics.

‘Are you saying that there is no God?’ asked Mary in a troubled voice. She had been taught by her parents never to question the ways of the Almighty, let alone His existence.

‘That’s not what I’m suggesting,’ replied Gaia, who realised the concept of atheism might be a step too far for Mary. ‘I simply wish that He wasn’t male. A female God would never have allowed cholera to take hold and would know how to put the Devil in his place.’

Mary was always shocked by Gaia’s willingness to challenge convention but never surprised. After Hercules Champion’s death, it had been anticipated that the size of the household would be reduced, with a smaller, more modest abode better suiting a widowed status.

Gaia, however, adored the grandeur and elegance of Somerset Place, which ranked among Bath’s finest crescents, and the house deserved a full complement of staff, and it was not her style to discard her loyal staff on the flimsy grounds of social expectation.

Returning to the chest of drawers, Gaia lifted out the last of the shirts, white cotton but with a dark red stain across its chest. At first, she wondered why Hercules had kept it, then recalled the occasion of their tenth wedding anniversary and the party they had thrown at the Assembly Rooms. Wine had been drunk and not a little spilt. It had been a memorable event for the best of reasons.

As, she hoped, the evening ahead — a birthday dinner she was holding for her closest friend — would prove to be.

‘Oh, Hercules, I miss you so,’ she said, momentarily hugging the shirt to her bosom.

Raising it further to her face, she breathed deeply, identifying the smell of his cologne.

*

MEANWHILE, BELLEROPHON ‘Belle’ Nash, the putative great-grandson of Bath’s most famous Master of Ceremonies, Beau Nash, was busy tying his cravat in his bedchamber.

His home, a townhouse on Gay Street by the corner of Queen Square, had an elevated elegance that matched the man. His task of dressing for the party, however, had been complicated by his companion, Gerhardt Kant, monopolising the bedchamber’s full-length mirror.

‘Do you für mich love have?’ said Gerhardt, staring at his beauty and untroubled by the unbeauty of his words.

The nephew of the late Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant of Königsberg had hit upon the question that for millennia has troubled humans more than any other, although not one that bothered his new ‘cousin’ just at that moment.

‘I wish you’d finish with the mirror, Gerhardt.’

‘I asked, if you for me love have, oder … ?’ repeated Gerhardt in what would have been perfectly fluent German had he not been at pains to translate his question into perfectly clumsy English. He gazed at himself dreamily in the mirror. ‘I see in the Spiegel a Spiegelbild but how know I it me is? Heiaha! So funny.’

Gerhardt’s ramblings broke the near silence of a still evening. From the bedchamber window, there was a majestic view of the city looking eastwards to the River Avon.

‘You and your Spiegel, Gerhardt: you are a flibbertigibbet,’ Belle protested. ‘Like young Narcissus, your reflection is your truest love. I shall have to start this knot again.’

Gerhardt did not care. Overwhelmed by his own image, he reached down to caress his hips and marvel at his yellow knee-breeches made of knitted silk.

‘Look at meinen body. Is it not a beautiful body, hein? But what is beauty, ja?’

It had been eight months since Belle had travelled to Berlin to add to his prized collection of Königliche porcelain. He had, instead, returned with a ‘second cousin once removed’ ten years his younger, whom he had met in the gardens of the late King Frederick the Great’s Sanssouci Palace.

Belle and Gerhardt had met on the terraces of the palace, walking on opposite sides of one of the long lines of trellised vines. Looking through the vine leaves, Belle had glimpsed a man of delicate features and elfin charm in effusive conversation with himself, and had pushed aside a trailing vine, heavy with over-ripe fruit, to make his acquaintance.

‘My,’ he had said, ‘what a lovely bunch of grapes.’

Sensing a mutual self-interest, they had explored the garden’s greenhouses together where oranges, melons, peaches and bananas grew in thick abundance. An hour in each other’s company had turned into days, days to weeks and weeks to seasons as Gerhardt returned with Belle to England. It was fair to say, however, that their relationship was not entirely tranquil.

While Belle largely enjoyed the younger man’s company, it had been awkward explaining to others how he shared a relative with Immanuel Kant. Living with Gerhardt also introduced him to an unwelcome new constant.

‘Belle, you love me, nicht wahr?’ Gerhardt asked again, viewing himself at different angles in the mirror, his eyes sparkling with obsessive energy.

Belle sighed.

‘Gerhardt, you beautiful creature, you’re becoming a bore. I have to put up with the company of city councillors all day, not to mention the vile beast in the magistrate’s court. Guildhall is ghastly enough; please don’t add to my woes at home.’

‘So, you love me not. Keine Liebe. I knew this.’

Belle’s second attempt at tying the cravat was nearing completion.

‘I said nothing of the sort, and I won’t pander to your nonsense. We have a party to attend, and Gaia will not want us to be late.’

‘So interessant a name: Gaia. Such a name have I hitherto heard not.’

‘Her parents clearly had ambitions for her. As did mine for me; it is no small burden being named after the slayer of the Chimera. No matter. We all have to live with the consequences of our parents’ whims. Now hurry up and put on your wig.’

Gerhardt, however, as was his wont, continued to gaze at himself.

*

GAIA HANDED HER husband’s wine-stained shirt to Mary, who placed it alongside the others in a battered trunk that had been pulled down from the attic. The two women had been clearing the room for three hours and the task was complete.

‘My husband did like a drink,’ commented Gaia.

‘He did, Ma’am. That was always the way with our Mr Champion.’

As she closed the chest of drawers, Gaia turned to peer at the stained shirt one last time.

‘I wanted to turn that shirt into rags, but he wouldn’t hand it over. And this is where he hid it,’ she reminisced. ‘Oh well, one shouldn’t become maudlin about a stained shirt. A pauper will be grateful for it.’

‘Are you sure, Ma’am?’ asked the maid, uncertain whether to shut the lid of the trunk.

Gaia was firm. Love, loyalty and friendship she embraced but she abhorred sentimentality.

‘It’s hardly the Shroud of Turin, Mary. I’d rather it clothe an unfortunate in the workhouse than have it feed the moths here. When you’re done, call one of the footmen to take the trunk away. Then go to the bedchamber and lay out my clothes for dinner.’

Mary nodded, but with some reluctance. She did not always agree with her mistress. If it had been her husband who had died, Mary would have kept the shirt for eternity, along with a lock of his hair. And while the maid had great respect for Gaia, she would certainly have waited the customary two years of mourning before touching his garments.

‘Are you thinking of any particular dress, Ma’am? The black silk … ?’

Gaia raised her hand. She had something else in mind.

‘No, Mary. I have decided that the period of mourning for Mr Champion is over. It may have been just twelve months, but I care not for the strictures of Cassell’s and nor would he. He would have wanted laughter in the house, not tears. Unless I marry and am widowed again, never more will I suffer crêpe against my skin. Dinner tonight is in honour of my dear friend Councillor Nash. It is the occasion of his thirty-fifth birthday, so something with gaiety and colour will be in order.’

As ever, Mary was shocked by her mistress’s flouting of social rules but also delighted. A broad smile broke across her face. She, too, had tired of black and grey and longed for her mistress to return to the colourful end of the wardrobe.

‘A party, Ma’am?’ declared Mary. ‘With Councillor Nash?! I had heard rumours but had not believed it!’

Gaia raised a hand again.

‘Not a party as such, but an evening for celebration. Councillor Nash has been working all hours in Guildhall preparing for the forthcoming visit of Princess Victoria, who will open our city’s new park. He needs an evening of light relief from his fellow councillors, so let us choose a dress with a touch of spring in it to match the season. But not too colourful. I have no wish to compete with Councillor Nash for flamboyance, let alone with Herr Kant.’

Mary’s mind was already working through the options. She knew Councillor Nash liked to dress up and that his Prussian relative had a reputation for sartorial excess. It would be a challenge to find Gaia an outfit that was colourful but sober. Not insurmountable, however, such was the extent of her mistress’s wardrobe.

‘What about jewellery, Ma’am?’ she asked.

Gaia hesitated. Out of practice for a year, she had forgotten how complicated getting dressed for a party could be.

‘Let me think. Lady Passmore of Tewkesbury Manor is among the guests, and I would not wish to compete with her pink diamonds. I suggest we stick to pearls this evening.’

With her spirits raised, Mary patted down the shirts into their new resting place and closed the lid of the trunk. The thought of once again having Gaia’s full wardrobe available filled her with excitement and she quietly blessed her mistress for forgoing a second year of mourning.

‘I hope you don’t mind my enquiring, Ma’am, but who else is attending the dinner?’ Mary asked.

Until Hercules Champion’s death, the house at Somerset Place had been renowned for dinner parties that routinely seated twenty guests. Gaia had enjoyed playing host and her skill had benefited her husband’s interests as a lawyer. Tonight, however, would be less lavish.

‘It will be a modest affair,’ explained Gaia. ‘Mrs Pomeroy of Lansdown Hill and Miss Prim of Gay Street are the other guests, so there will be six of us. Mme Galette is at work in the kitchen preparing Councillor Nash’s favourite dishes: cheese soufflé followed by rib of beef. I believe she also plans a steamed sponge pudding for dessert.’

Mary’s feet could not help but shuffle in excitement.

‘A soufflé, Ma’am! I do so love a soufflé. There’s always such a rush to get it upstairs to the dining room before it sinks and …’

‘Now Mary,’ interjected Gaia, ‘we seem to be finished here, so go to the bedchamber and lay out my clothes. Off you go.’

Mary did a little curtsy and hurried from the room, closing the door behind her, leaving Gaia standing alone.

*

‘THE WIG, Gerhardt.’

Gerhardt threw his hands in the air.

‘Mein Gott, the wig. I have the wig to prepare forgotten. Why reminded you not me?’

Gerhardt’s failure to take responsibility infuriated Belle.

‘Because, unlike you, I have moved on from the eighteenth century and don’t care to wear a wig. You really must speed up. It is not acceptable in England to be late to one’s own birthday party.’

If Belle thought he could hurry Gerhardt he was sorely mistaken. An unusually large, voluptuous wig was removed from a box and liberally covered in a cloud of Cyprus powder scented with clove and rose oil. A process that might have taken thirty seconds now stretched to fifteen minutes.

Belle opted to lie on the bed and read a book. Organising a royal visit to Bath was a lot easier than helping Gerhardt to dress. After a chapter of Ivanhoe, his companion had finally donned the wig.

‘Gut. This is now fine,’ said Gerhardt.

‘Well done,’ replied Belle, swinging his legs off the bed and thinking for an instant they might be ready to depart. ‘So, are you set to go?’

‘What do you think?’

Belle smiled.

‘You look beautiful, of course,’ he said.

Gerhardt studied himself in the mirror anew.

‘Natürlich. I always perfect look. I am perfection. I am the Konzept of perfection.’

‘Apart from one thing,’ Belle noted. ‘You’re not wearing any shoes. And now you’ve got that ridiculous wig on your head, you can’t bend down to put them on.’

Gerhardt stared at his stockinged feet in dismay. Having behaved like a petulant peacock for the past hour, he needed help.

‘Schnoodle doodle, das ist crazy. You must it for me do, Belle. Help me meine shoes to on put.’

‘You’ll have to ask more politely than that to get my help. And more idiosyncratically.’

‘Are you mad? I have already zwei hours getting dressed spent!’

Belle placed a hand on his companion’s shoulder in an effort to calm him.

‘Manners, Gerhardt. Say please and I may just do it.’

His Prussian companion stared at him in astonishment, teetering on the edge of rage. Then, remembering that it was Belle’s birthday, he acquiesced.

‘So, tonight am I the Arschkriecher to be. OK, very well: bitte Belle, please me with meinen shoes to help.’

‘I’d be delighted,’ said Belle, dropping to his knees.

‘Und while you are down there,’ Gerhardt added, running his fingers through his companion’s hair. ‘Happy Geburtstag, dear friend.’

*

GAIA HAD STOOD in her late husband’s dressing room alone. Alone: a solitary word, like ‘widow’, that clings to and defines the bereaved.

With the closing of the door and the departure of jolly Mary, her spirits had fallen. For all the talk of the end of mourning, the maid’s absence had left a shadow. Gaia had found herself staring at the closed door.

‘When someone dies, there is always silence,’ she thought. ‘How I wish it would end and happiness return.’

She walked to the window that looked over the Royal City of Bath. It was a splendid view. She wondered how many times Hercules had stood in that very spot taking pleasure from the beautiful buildings of honeyed stone. Here on top of Sion Hill, she could see the roofs of Royal Crescent and, to their left, the outline of Bath Abbey, on whose edifice sculpted angels climbed to heaven.

Standing where her husband had stood ten thousand times, she moved her face closer to the window and for a moment imagined raindrops outside. But the evening was clear, and they were not raindrops she saw but tears reflected in the glass. Tears cascading down her cheeks.

‘Hercules, how could you have left me?’ she said, weeping openly. ‘Look at what’s happened. Thirty-six years of age and I have nothing. I never gave you children, but we were together and now I am left without husband or purpose in life. Come home, Hercules. I want you to come home.’

She leant on the sill for support, blinded for a moment by loss. At that moment, Mary knocked on her door.

‘The first guest, Ma’am, has arrived early,’ she said. ‘Miss Prim. With her knitting. And the footman says Lady Passmore’s carriage has been seen waiting in its usual place. The Champagne has been opened, so we had better hurry and get you dressed for the dinner.’

Drawing air into her lungs, Gaia recovered her composure. She was not a person to be easily defeated. Far from it. And, as is so often the case, out of the depths of misery, resilience grows. When she looked up, the reflection in the glass was the handsome face of a woman of granite determination.

‘The silence of death is bad enough,’ she said sternly to herself. ‘I’ll be damned to let melancholy occupy my husband’s place. What you need, Gaia, is a plan of action. It’s time to get on with life. There are friends to care for. And a future to be faced.’

With those words, she dried her cheeks, turned and, with a firm stride, left the room.