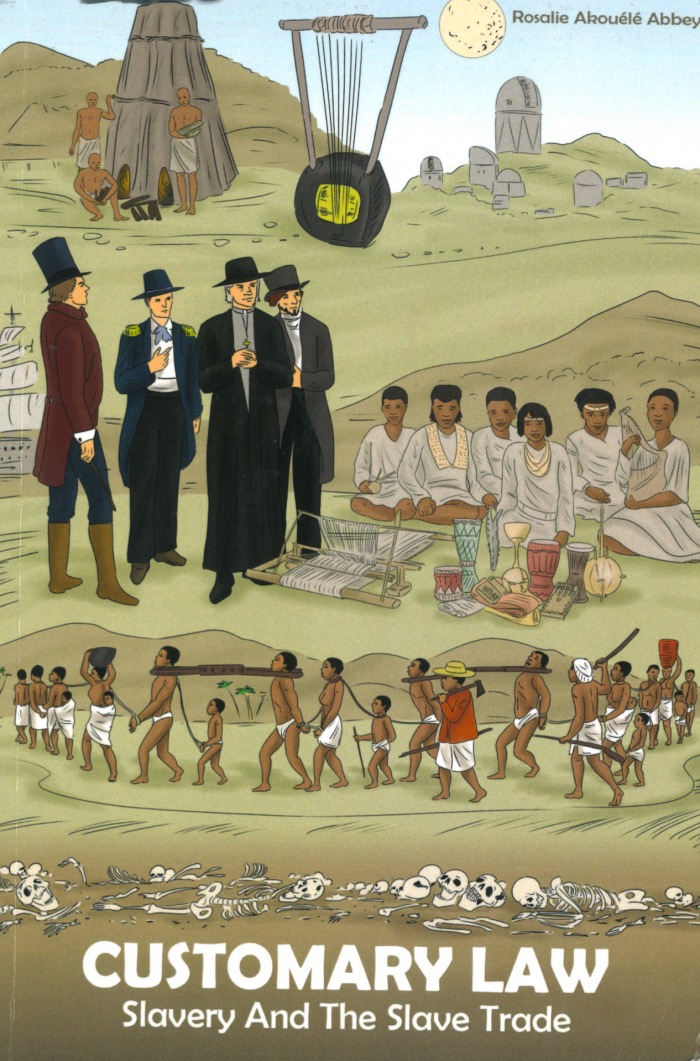

Customary Law: Slavery and the Slave Trade

Customary Law: Slavery and the slave trade Rosalie A. Abbey

INTRODUCTION

To understand West Africa's conflicts since the independence's period, one must confront an aspect of its past, which was marked by the casual selling of men, women, and children. One must confront the slave trades and the concept of slavery. But does CustomaryLaw recognize the definition of "slavery" as it is known and accepted still today, which seems to fit Africa as a glove fits a hand?

Should one forever accept the definition of slavery, as conveyed to the rest of the world by Arab chroniclers and by European traders since the 10th century? Or must one also listen to the hesitations of some other less interested, neutral witnesses that are West Africa's institutions?

Is the land, in fact, by its innumerable and bloody conflicts, trying to tell us that a gross and terrible mistake had been made of the meaning of its institutions, particularly of slavery; mistakes made by the aforementioned early chroniclers and explorers, which had allowed Africans themselves to help transform and debase these institutions, thus creating gaping wounds which refuse to heal? In other words: besides the Horse and the Gun, what and where were the failures of Customary Law?

What caused Africans, kings or ordinary individuals alike, to make a habit of trading other Africans for years and centuries?

The answers to these questions lay, at least partially, in the dusting off of Customary Law. This legal structure which originated from events as told by the various versions, partial or complete, of the " myth s" (ll, used religion to create and preserve the social order it desired.

Indeed,Customary Law, an unwritten law, had identified this human aspiration, which is freedom to do whatever pleases oneself, and invented a mechanism to thwart it, or in any case to control it. West Africa's sense and meaning of slavery is precisely this instrument of control. As a tool for exclusion, it had helped choke attempts for changes, which surfaced in past centuries or perhaps millennia, within West African societies. The spirit of customary law, thus, having its roots in this desire to suffocate the will to change, to progress, is

-5-

organized around the principle of division. Principle which forbids interactions between communities and clans, unlike the mixing of populations brought on by the slave trades. The tool, thus invented, had helped maintain established order. It was, therefore, an important piece of the legal indigenous apparatus.

However, like most of the regional institutions to which customary slavery is linked, this native institution showed its limits and revealed its risks when it found itself confronted with the challenges brought upon it by the coming of Arabo-Berbers and the arrival of European traders a few centuries later. In the face of these dangers to their communities, African rulers failed to act and reform this legal and religious apparatus.

On the contrary, on their watch, there were to be failures. The tool that helped quell the curiosity of innovators (astronomers, astrophysicists, blacksmiths, botanists, electricians, masons, etc.) by controlling their right to be free and by keeping them on the margins of society, ostracized. This ,same tool helped sell men, thus espousing, almost perfectly, the new definition of slavery.

Because of its position at the core of the legal systems, the failure of this major tool had multiple repercussions on the rest of native institutions. It also ripped open, once again, one of the supports of Customary Law: the past.

The tribal, and ethnic and religious strife of today; the grave, gross, and repeated abuses of human rights in West Africa; are the results of these drifts and failures of the Customary Law. They are also the results of past conflicts and ill-thought choices that the slave trades, both Muslim and Atlantic, rejuvenated. As they formally took control of West Africa, colonial lawmakers tried, however, to set up novel legal systems on patches of land under their control, which they seemed to be discovering only then.

In reality, as well aware as they were of this part of the continent's tragedies, these legislators proceeded with caution in carrying out their endeavor. Caution, though, was not to be among the concerns of West Africa's legislators, who replaced the former in the years following the region gaining political independence in the 1960s. Various reasons are invoked to justify this eagerness and this boldness of

-6-

the new legislators to make it their task to finish the project left behind by colonial powers.

Indeed, African legislators were radical, no attempts were made to take into account the past, even as they were aware of the muffled resistance some communities already offered the imposition of Islamic Law. The stated goal was the imposition of the legal systems introduced by Colonial Powers, on all the communities of the region. [21

These legal systems, in their spirit, intent, and objectives are opposite to that which inspired the inventors of Customary Law. Has this latest transplant been successful? Or should one also see in West Africa's conflicts a sign that this operation failed?

Would it not be wise r and more helpful to first turn to Customary Law in a search for possible explanations and solutions for the wars, the conflicts, unabated throughout the region, and explore the attachment West Africans s till have for the archaic legal apparatus? ls it not time to confront customary law before dismiss ing or discarding it?

After all, the law is a reflection of history l3l a n d an expression of the kind of order society wants to establish for itself.

Only then, perhaps, would one be able to start to understand why Africa remains stagnant and ravaged by conflicts, horrendous conflicts. Only then, perhaps, the transplants necessary to keep up with the march of the rest of the world would fare better and truly drag the continent on the road to demonstrating true consideration for human rights, therefore allowing its people a sense of security and freedom for a " better tomorrow."

PART I

Theoretical Issues

CHAPTER I

West African Customary Law and Social Sciences

Customary Law's meaning here is to be taken as a whole, not only in its aspects, which did go through some changes during colonial times. There fore, its other characteristics, which were " contrary to the values of civilization" left unexplored by colonial powers, must

also be put under scrutiny _[4l •

One must not forget, as J. Fage reminded, that one of the goals stated by European powers for the formal colonization of the continent in the 19th century, was to bring peace to it. Suppress practices contrary to our values of civilization, as many colonial administrators saw it [5l, a euphemism which also meant to acknowledge the tragic consequences of the slave trades.

Thus, Customary Law in this work focuses on most of its aspects that are not dealt with by jurists, and rarely by historians, particularly traditional slavery (which seems to persist in the form of domestic slavery) and some other seemingly striking features recognized among all West Africa's communities, that is, the status of land, rules of filiation and kinship in general, and their implications.

The meaning of traditional slavery, which emerged through examination of events from the past, as it is hoped to be shown, came to merge almost completely first with the Arabo-Berbers' view of the concept at first, which added numbers to it. With the Europeans' arrival the numbers of enslaved Africans expanded as the Atlantic slave trade took off.

. Ironically it is traditional slavery, the institution ignored in legislative renovation by colonial authorities, which will, in revealing

itself , prove the key for a better understanding of Customary Law as a whole.

Important still, it is this very feature of the law that provides the

main tool for a most credible reading of the region 's past.

Section I - Remarks

I - Concepts, Notions, and Definitions

A - Some Early Social Scientists

Although this study limits itself to the examination of West African Customary Law, and its possible connections with traditional slavery and later on with the slave trades, the discussion below will go briefly through some of the notions, concepts, and definitions first developed by social scientist s because of the considerable impact they have on the study of traditional institution s.

The nineteenth century's generation of social scientists, led by Lewis H. Morgan and H. Spencer, for example, made no mystery of their approach to the study of primitive societies, which was based on the Darwinian theory of evolution. (P.A. Erickson & L.D Murphy: "A History of Anthropological theory," p. 70). Thus, in his " Systems of Consanguinity...of the Human Family," Lewis H. Morgan, shortly after the middle of the 19th century, brought to scholars ' attention his description and understanding of kinship through comparative philology of North America Indians and the way they organized themselves into systems and structures l6l .

Besides the notion of kinship, this late st observer introduced additional concepts such as a "classificatory system of relationships," "matriarchy," and " hordes." His definitions of these concepts are now part of the standard tools of analysis in social sciences.

About the same time, E.B. Tylor, in " Primitive Culture," sought to study all aspects, mental or intellectual, of primitive life while H. Spencer focused, for his part, not on aspects of life in society but on society itself, viewed as an organ with different parts and at various stages of evolution. (" Principles of Sociology ," vol. II , pp.240-43, 311).

Among the variety of concepts, of which H. Spencer is the main proponent is that of "undifferentiation"on a political and social level (see for example, vol. II pp. 288-289, pp. 306, 308-310).

The generation of social scientists which follows these early figures pursues aspects of these previous analyses mentioned above.

From E.B. Tylor and A. Lang in "Myth, Religion, and Ritual," for example, to J.G. Frazer in his various volumes of the " Golden Bough," comparative studies of myths and religion of the ancient Western world and those of primitive communities around the world were conducted with the goal of retracing the early steps of western civilization[71_

Perhaps the most eclectic of these three, J.G. Frazer also adopted the previously discussed theories and made the connections between the rules of marriage, prohibitions and non-prohibitions of it, depending on the communities involved, in what has been the grand theory of religion, or lack thereof, among primitive communities - totemism. ("Totemism and Exogamy, Vol. 1, for example p. 3, 15, 101, 148; and as far West Africa is concerned, see the second volume of the same, Chapter 14, p. 542- 608).

Among the other aspects of these investigations are E. Durkheim's focus on the cause for the existence of these rules of exogamy or the act of incest ("La prohibition de l' inceste" in l'Annee sociologique 1897, 1, p.10-11).

In his "The Division of Labour in Society," E. Durkheim also sought to explore the implications of the concept of undifferentiation developed by H. Spencer's view of society as a living organism (p.129-130).

One of the other themes developed by E. Durkheim in "The Division of Labour in Society," was the examination of the consequences for the Law, which this division of labor, itself a consequence of un differentiation or differentiation create or does not create within prime or ancient societies; as in modern societies, as well (p.68-69). In doing so, he sought also to validate conclusions, some attributed to Sir Henry Maine rs1, that primitive law is essentially directed to the repression of crimes.

For a considerable period of time Sir Hem-y Maine had been the sole voice among jurists who stayed away from this field while social scientists were elaborating on modern concepts, ideas, and their definitions.

B - Social Sciences and Customary Law

Indeed, while jurists kept to the "dogmatic" definition of the law,in the sense J. Carbonnier defined this word ("Sociologie Juridique,p.21), Sir Henry Maine, also a colonial civil servant, conducted investigations of India's customary law, which he compared with early European law. ("Dissertations on early law and customs," see for example pp.3-4, 43-44, 36-38, 93, 162).

By the time jurists such as Roscoe Pound began to add their voic es to those pleading for a cooperation (American Journal of Sociology vol.18, May 1913 no 6, pp. 756, 760, 763) between the two discipline;concepts, notion s, and definitions elaborated by social scientists had already firmly taken root. As a result, jurists interested in Sociology or Anthropology and colonial servants made these too ls their own in their attempts to understand Customary Law.

Colonial times were, in deed, an interesting time for jurists to observe how two philosophies of mies could cohabit; to see if rules borne out of different way's of approaching society's problems and setting norms to govern whole communities could eventually merge, or if customary law would not tole rate changes. These were confusing times, too.

Section II - Impact of Theories on the Understanding of Customary Law

I - Theories and Facts

A - Erroneous Mixture

The dawn of colonial times saw the continued growth of social

theories, fed by information collected in the field by early colonial B civil servants, who, in turn and in many instances, tried to match the facts on the ground with existing notions and concepts, even though,

in many instances, neither these facts nor rules of Customary Law coincided with these assertions.

The study of the region's (West Africa) religious ideas stimulated this mutual feeding of ideas.

In a mixture of observations and interpretations, theories of fetishism, on naturism, even of monotheism , and above all, that of totemism (9)l, all find applications on the ground based on reports coming from travelers who visited various primitive communities .

Thus, Le Herisse, for example, explained the religious ideas of the peoples of Dahomey (today's Republic of Benin) by citing "... monotheism," "fetichism," " naturism" ("L'Ancien royaume du Dahomey," p.96- 101, 108-110).

Observations also emerged about West Africans' belief in a higher spiritual power, which they place above all their divinitiesl(10).

Yet the discussion ignited by Arab chroniclers and taken up by Europeans remains unabated, as to whether or not those primitive communities could think in terms so abstract as to imagine the existence of such a higher power.

As Sir J. G. Frazer explained:

" . .. the rudest savages as to whom we possess accurate information, magic is universally practiced , whereas religion in the sense of a propriation or conciliation of the higher a power seems to be nearly unknown... " ("Toternis m & exogamy," vol.Ip. 141).

This work by Sir J. Frazer is based, in part, on observations he obtained through colonial servants on the ground, such as A.B. Ellis,

M. Delafosse, C.H. Harper, and Tautain whom he abundantly cited for the part in which this author dealt with West Africa.

These field observers made valuable remarks, but in their observations, a great many of the same often lacked the sagacity displayed often by A.B. Ellis, J.D Clarke or M. Delafosse, for instance.

B - "Facts" Made to Fit Theories (More Examples)

For example, M. Delafosse, whom Sir J.G. Frazer cited himself (see for example, vol. II, pp.552, note 1), remarked with some validity

on a related topic to the one discussed by Sir J.G. Frazer.

In dealing with conditions and rules of marriage among a number of upper West Africa's communities, M. Delafosse wrote, in one of his volumes of " Haut-Senegal Niger", these lines:

"... endogamie et exogamie" .- Among most of the peoples who practice the custom of the diamou or clan names (Mande, Tukulor, Songai, Senufo, Voltaic, ), marriage was allowed, originally, only between future spouses who belonged to different diamou

(...)' this was because, initially, all those who bear the same diamou were, in reality, part of the same family and were related; this still occurs in small villages, where people of the same diamou are more or less cousins; thus one can still hear that such man cannot marry such young woman because both of them bear the name " Diara"; in reality, there is not, here, exogamy resulting from a system of totemic clans, the obstacle to the marriage simply originates from the kinship [that links the two]." ("Haut-Senegal-Niger," T. Ill, p.80).

Thus, their views and those of the theorists, still influenced by their own religious ideas, were not free of biases, as illustrated by Sir

J.G. Frazer's approach, which is to take this information literally as reported and insert it in their works; an inefficient method, for this could not and had not brought out the realities of West African religious principles and practices and their ideas about this phenomenon termed " totemism" ; religious principles and practices, which in part, sustain Customary Law.

M. Delafosse's quotations above mean that totemism plays no role in the rules of marriage, which is true to a certain extent, but he did not give his understanding of the notion of kinship or diamou.

Another instance of theory about facts and rules on the ground, which will be touched on only briefly here because of further analysis shortly (pp. 16-29), is the wholesale transfer to the continent by A.R. Radcliffe-Brown of Lewis H. Morgan's theories which give marriage as the origin of kinship; thus linking kinship and marriage and therefore linking together rules governing both of these institutions.

Comments

Missing rubrics

I believe I am supposed to add a copy of my book cover and a photo. I will shortly. Thanks for your patience.