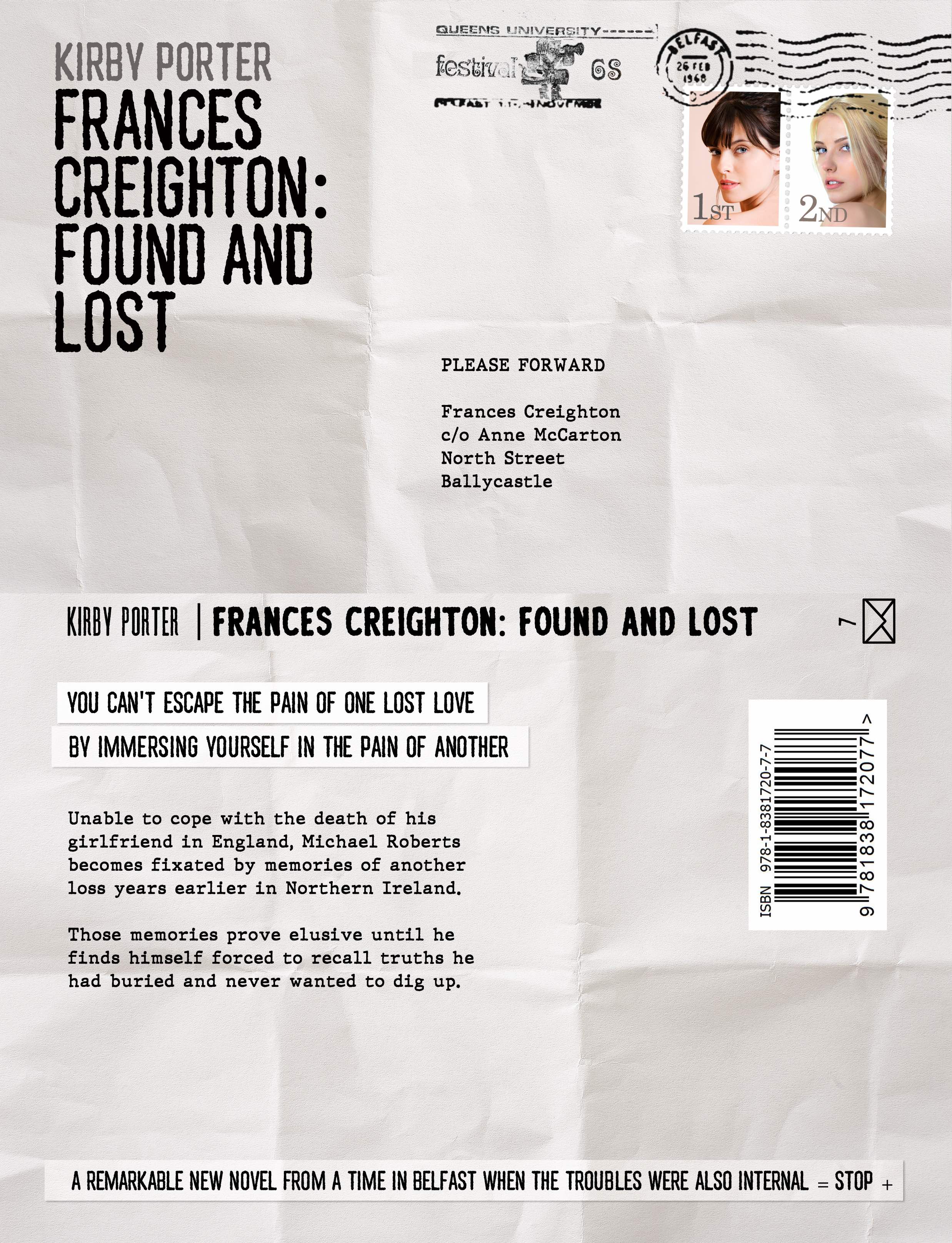

Frances Creighton: Found and lost

Unable to cope with the death of his girlfriend, Michael Roberts tries to find comfort in memories of another time and another place when he was in love for the first time. But that first time was as a schoolboy in Belfast, at the start of The Troubles in the late 1960s, and in a culture dominated by divides that weren’t just sectarian.

142 days. It sounds longer, somehow when I say it like that. 142 days. Rather than just less than four months which would have been another way of saying it. From 3 May until 22 September. Not a long time, no matter how I say it. Not long enough. Not nearly long enough. That’s what I thought, anyway, as I stood in the rain with all the other embarrassed mourners in that North London cemetery, trying like them to avoid looking into the open grave for fear of what I might see there. They hadn’t wanted to come, probably, as I hadn’t, but came just the same. For the sake of appearances—a duty that couldn’t be avoided. I wondered why they had come. There were only a few who had any real right to be there, those who’d loved her and who’d never now be the same again. Her mother and father clinging together for support, as they’d once clung together in her moment of conception, never thinking it would end like this. Her brother and sister still too shocked at her death to understand what it would mean for them. Others too that I didn’t know, whom I had heard her talk about only in passing, in reference to events I expected I’d catch up on later, when there was more time, when the present could give way safely to the past. And me I suppose, though I had only been with

1

her for those 142 days, had only been in love with her for that short time. Me more than all the others.

I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: and whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die.

Words of comfort which brought no comfort at all. I’m not even sure that they were used that day. I was too far back to hear properly what the clergyman was saying. When I got home later that evening I looked the words up in an old Church of Ireland prayer book that I’d won as a prize for good attendance at Sunday school when I was ten and that had crossed the Irish Sea with me when I was twenty-five. Don’t ask me why. I didn’t even know what religion Angela was or what she believed in. I was standing too far back, lost in the crowd of second-divison mourners, also-rans in grief and sadness. All I could hear was the sound of the traffic roaring past the cemetery gates, cars and lorries all going too quickly so that they could spend more time in the inevitable holdups that they would find when they got there. I couldn’t understand it at first, all that noise. It was a graveyard, for goodness’ sake. It should have been quiet and peaceful, a place apart, cocooned from the noise of life and the living—separate. Stupid I know, like reading the words of a funeral service that had not been spoken. But what else do you think about when you’re trying not to think at all, when you’re trying to shut everything out and pretend that it hadn’t happened, that you’ll wake up soon and it will all be all right, that even if it isn’t a dream it won’t really matter and you’ll still be able to survive. Perhaps that was why it was so easy to start thinking about you again. Just random thoughts to keep the fear at bay, not to bring you back to me again.

2

At some point I must have moved closer, unconsciously claiming the role I had never before chosen to profess. The clergyman had stopped talking. The brother came forward, stiff and proud. I could hear now. He read a poem; her favourite, he said, though I’d never heard her speak of it in that way—one that I had read to her as we lay in the close confines of my small London flat after an afternoon of wine and love-making. How had he known it was her favourite when she had never told me, when she’d said only that it was the sound of my voice she enjoyed listening to and that I was like no one else she had ever met?

One side of the potato-pits was white with frost— How wonderful that was! how wonderful! And when we put our ears to the paling-post The music that came out was magical.

The light between the ricks of hay and straw Was a hole in Heaven’s gable. An apple tree With its December-glinting fruit we saw— And you, Eve, were the world that tempted me.

To eat the knowledge that grew in clay And death the germ within it! Now and then We can remember something of the gay Garden that was childhood’s. Again

The tracks of cattle to a drinking-place, A green stone lying sideways in a ditch Or any common sight the transfigured face Of beauty that the world did not touch.

Perhaps that’s it as well. A sense of exclusion, of thinking that I didn’t really know her at all, that there hadn’t been time, that we were still only exploring how much we loved each other. I don’t know. I don’t think I know anything anymore.

3

The ceremony was over. People were moving away, purposeful once more, glad of the opportunity to be doing something to take them away from the uncomfortable closeness of death. I didn’t know what to do next. I knew that I should speak to her parents. I should have spoken to them already—as soon as I heard of her death, that awful afternoon when the office went quiet and the woman on the switchboard started to cry and the pain in my head just got worse and worse. When I was sick in the toilet and had to be taken home and was told over and over again how sorry, how very sorry, everyone was. I should have gone then. Explained who I was, joined the family circle of grief, explained that I was more than just someone who knew her from work, offered up some words of condolence. But I didn’t know what those words were or how I would have said them. I wanted to go to them now and say: ‘I’m Michael. I loved your daughter. I loved Angela. I was going to marry her one day. One day. Help me. Comfort me.’ But the words seemed to belong to someone else, as though, by dying, Angela had stolen them from me, as though they didn’t mean the same thing anymore. I was a stranger again, as foreign as I became in England after leaving Belfast. Nothing in my earlier life had prepared me for this moment. The formalities of speech that I would have used there seemed out-of-place here, out-of-place and unwanted like me, even though I now speak of London as home, even though it’s years since I’ve been back to where I grew up. Perhaps that’s it as well. Perhaps that’s exactly it. I pushed myself forward and said something, anything that came into my mind. I told them my name and said how sorry I was, hoping that that would be enough, that they would see me and realise that I was the person Angela used to talk to them about, and how sorry they were that we had not managed to meet before, and how glad they were that I was there. I don’t think they heard me. No one was really there.

4

They were simply going through the motions, lost in thoughts of their own, trapped, like me, in places where things like this didn’t happen to people like them. I held out my hand and her mother clutched at it as she looked over my shoulder at somewhere far, far away. ‘You’ll come back to the house of course,’ her father said. ‘Angela would have liked that. She often spoke of you.’ Her mother nodded absently. I wanted to feel validated by this, as if I’d been recognised, as if they knew that we had met at work and fallen in love, but it was obvious from the way he looked at me that neither of them had any idea who I was, that he had been saying the same thing to other friends of hers all equally unknown to him. And I didn’t want to go back. I wanted to be by myself because that seemed to be the best thing to do. I didn’t want to have to be polite to anyone, to talk at arm’s length about everything except the one thing that everyone was thinking. I couldn’t escape though. Her mother’s cold fingers had locked onto me in a hold I couldn’t break. Her husband was probably right in any case. Angela would have liked it. I allowed myself to be pushed towards one of the cars that was going back to the house. I didn’t know whose. A relative, a friend of her father’s, perhaps: someone who had known her as a child. ‘You’ll take Mr … . You’ll take him back to the house, Tom. Angela would have wanted it.’ Tom said he would and we exchanged greetings as I slipped in beside him. ‘Rotten weather,’ he said before lapsing into silence. And that was that. Back to the random thoughts that were the cause of it all, as we pulled out of the cemetery and headed off down the main road and past you—Frances!— though even in that moment of recognition—Frances?—I knew it couldn’t be you.

5

You were standing in a shop doorway looking quickly from side to side as if you wanted to go somewhere but were unsure which direction to take. I only saw you for a moment before Tom’s car moved on, speeding me away from you again. There was really nothing remarkable about the sight. Just a girl in a doorway, a girl who could just as easily have reminded me of Angela as of you, but as I didn’t want to think about her, it was easier to hold onto the image and try to burnish it into being you. Not that I could. It had all happened too quickly and the image quickly drained away, leaving not emptiness, as I had expected, but another image— another girl in another doorway. And this time there was no mistake: it was definitely you. Frances. After all these years. Do you remember? It was when you worked in that pet shop on Donegall Street on Saturdays and during school holidays. When it wasn’t busy or when the noise and smell of the animals became too annoying or when you had tired of the constant talk of the other assistants, you’d go outside to see what was happening. I often saw you there, standing in the doorway. It always gave me such a thrill, the thought that you might be waiting for me. I suppose that’s why I thought it might be you today. I would come round the corner and hope that you would be there, stopping briefly to prolong the agony of expectation so I could look at you peering hesitantly up and down the street through eyes that must have been shortsighted though I never saw you wearing glasses. And when you did see me your smile more than made up for all the disappointing days when you weren’t there but were locked inside with your animals, with no time for more than a quick hello before you shuffled me outside again with promises of seeing me later. And then you too were gone. It seemed all so long ago. Before we had really grown up, before our Belfast streets had slipped into uneasy war. Frances. I had forgotten all about

6

you, put you away with all the other forgotten things of yesterday: the toys and games and people I thought I no longer needed. But now, here in London, you had come back and for a moment I was back in the city centre, keeping a close eye on you until the pet shop got so busy that you had to slip inside with no time for even the briefest hellos. I smiled as you disappeared but something else was wrong. Why today? Why today of all days? What were you up to? What was happening to me? I suddenly felt cold and gave a shiver. I didn’t want to think about you anymore. But that only brought me back to the thoughts of Angela I so wanted to avoid. I turned instead to Tom. ‘I’m sorry,’ I said. ‘I don’t know the family very well. Are you related to Angela?’ He glanced at me quickly before looking back to the road. ‘I’m her uncle,’ he said, with some difficulty. ‘She’s my sister’s daughter. Such a lovely girl. I remember the day she was born, I remember her going to school, and how her parents worried. Parents worry about their children when they’re young. How they’re going to cope. Whether you’re doing the right things. And then before you realise it they’re out of your reach and you think your job is done. You don’t have to worry anymore because they can look after themselves and you haven’t done so bad a job after all. And then this. You never think of them dying before you do. How could you? Such a waste, such a terrible waste. And the bastards who did it didn’t even stop. Didn’t even stop to see if there was anything they could do.’ There were tears in his eyes as he spoke and it was only then that I noticed how he gripped the steering wheel, as though he needed something solid to hold onto in case he fell to pieces when he had to be strong for all their sakes. I realised too that I did not know the Angela he spoke of—the

7

baby, the young girl, the teenager—or how they related to the Angela I thought I knew. And that now seemed unbearably sad. My Angela was someone whom I alone knew, a part of a picture that would never be completed. It was almost as if I was at the wrong funeral, had come to say goodbye to someone entirely strange to me, whom I knew only in passing. The funeral was all about them saying goodbye to their Angela, leaving me with no one at all. I cried then as I had not been able to do before, Tom’s grief seeming to reinforce and expand mine. I don’t know why I cried. For Angela. For myself. For you too in a way. For the hopelessness of it all. For the waste. For the sheer stupidity. The tears ran down my face as I stared out at the rainswept streets, not knowing where I was or where we were going. Not caring either. Tom beside me said nothing. Perhaps he thought it strange that I should react as I did but he took one hand off the steering wheel nonetheless and laid it gently on my arm. I felt its soft pressure for a moment and then it resumed its original position. Strangers, we mourned together someone whom we both had loved, a shared grief which brought its own comfort to something we didn’t understand and would never accept. I went back to the house with him and stood around drinking sherry and eating shortbread, laughing too loudly at jokes that no one thought especially amusing, talking about nothing in particular with anyone who would pretend to listen, eager to be away but not sure when to leave or how to make my excuses. The moment gone forever when I could explain who I was and how much Angela meant to me. I shook hands with her mother and said again how sorry I was, seeing in her eyes a reflection of my own fears, of wanting so much to be alone yet dreading the very thought of it. Then I went back to the sherry, hoping to overwhelm the numbness that was threatening to envelope me. It must

8

have given me the courage at last to go when everyone else was still chatting nervously and clinking glasses, glad at least that no one had questioned my right to be there or demanded to know who exactly I was. I set off for home, not really sure what direction I should be taking. All the time it kept on raining and raining until I was soaked through and miserable. I didn’t care. I walked aimlessly along roads I had probably walked along already. I was lost and I had drunk too much but I was also avoiding going back to my flat. There was nothing for me there. When the effects of the sherry started to wear off, I was left feeling cold and depressed. I tried to keep my mind blank. I didn’t want to think about Angela, about Angela’s being dead. My mind couldn’t grasp the significance of it. I couldn’t understand this total absence of her. I wanted to keep on pretending that none of it had happened, that she hadn’t visited her friend in Dorchester but had stayed with me, that she had been safe indoors instead of on the open road when the car had come speeding round the bend. That I had been with her to protect her, to keep her safe. Feelings of guilt added to all the others. My mind wouldn’t stay blank. All I could think about was her and how I had let her down. ‘It’s only for the weekend, Michael. I’ll be back early Sunday evening. Come round about seven and we can go for a drink or something. You know you could still come with me if you liked. I’m going on Friday evening after work. I’m sure Susan wouldn’t mind. Think about it anyway.’ You can see why I needed something else to think about. Something to crowd out the dark thoughts of death that had taken hold of me and wouldn’t let go. And so I thought of you, my girl in a doorway, back from a long holiday. It seemed such an easy thing to do, a long slow slide into the softness of memory. A mistake. A very big mistake. I can see that now but how was I to know? I should have walked away while I still

9

had the chance. That’s what I would normally have done. Walked away, just walked away. I started again with the image of you in the doorway, fixing it in my mind like a frayed poster of coming attractions outside a cinema long closed. Then I tried to see what was happening in the pet shop, to smell the animals again, to conjure up old Mrs Kelly who owned the shop and who had told me my fortune the first time I met her and said I would marry a girl whose name began with the letter F. But the images jarred and shifted and were lost to me as if, with your defiant smile, you had decided to keep me standing in the rain waiting for you to speak. As though you only wanted to be remembered: nothing else. Eventually I stumbled home, glad now to be out of the rain, glad that I hadn’t met anyone in the hall or on the stairs who would ask me how I was and say how sorry they were about Angela. And so young too, so much to look forward to, it’s hard to understand sometimes, isn’t it? I changed my wet clothes, put the whole lot into the washing machine at one go, did not worry about whether colours might run or fabrics shrink. I ran a bath for so long that the water spilled over the edges when I got in, and I stayed in it until it went cold and was no longer a comfort. Then I got out and put on my pyjamas and a dressing gown even though I didn’t want to go to bed. I didn’t want to do anything. I poured myself a glass of Midleton from the bottle Angela had bought me for my birthday even though I had told her not to and which I had been keeping for Christmas or a special occasion. I’d meant to drink it with her and teach her to appreciate its golden smoothness and let it help her through the dark winter months.