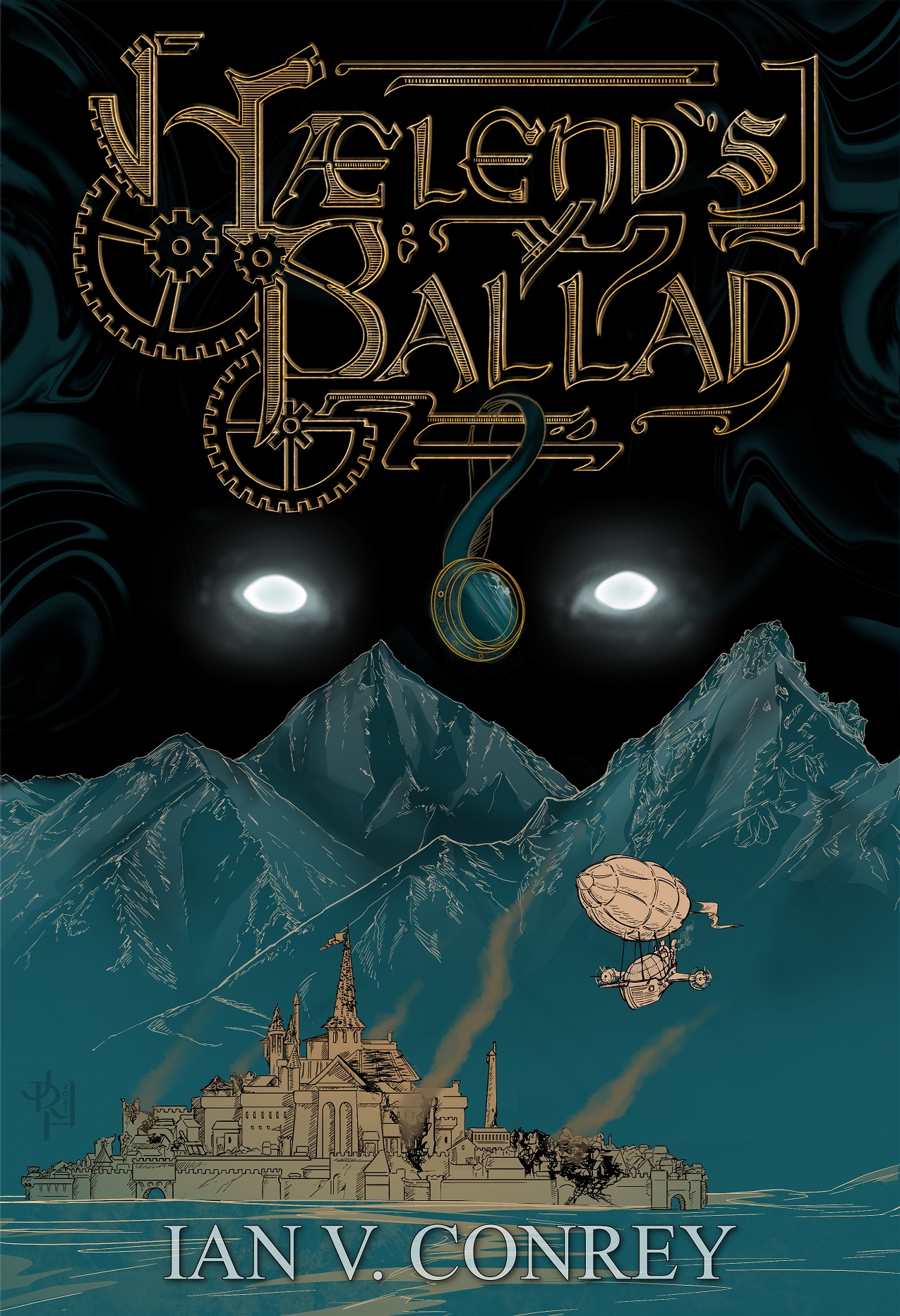

Haelend's Ballad

Dark Horses

As the breeze blew the tails of Eilívur’s coat behind him, he peered across the Llynhithe port docks to the rising tides of the Swelling Sea. He pulled the letter from his pocket and fiddled with the corner as his gaze wandered to a group of sailors, gesturing and shouting while they raised the sails upon the foremast of a great ship. A boatswain pointed toward the outhaul, and several men gripped the rope, tightening the sail which billowed out in the wind.

“Blasted air’s gone chilly again,” came a voice from behind.

Eilívur turned as Commander Jótham approached in his black uniform, which only seemed to accentuate his pale skin, even by Daecish standards. “Llynhithe isn’t so bad,” he replied. “At least you can see the sun.”

Jótham grinned, revealing his ghastly brownish-gray teeth—unfit for an officer. “With all due respect, Commander Tyr, you haven’t been here but two days. You’ll grow to hate it, too.” He pointed to the letter in Eilívur’s hand. “Are those my orders?”

Eilívur faintly nodded and scratched his cleanshaven face. His eyes wandered to a row of crooked wooden buildings. Gray thatched roofs sagged around the seemingly rotting beams beneath them. “Anywhere we can get a drink?”

Jótham let out a hack, which Eilívur assumed was meant to be a chuckle. “A drink? Commander, this isn’t Everwind.”

Eilívur didn’t bother replying.

Jótham rolled his eyes and pointed down the road. “There’s a tavern not far from here.”

Stepping through the open entryway, the smell of sour milk and lantern oil filled Eilívur’s nose. Several Sunderian men, clothed in brown leather tunics and jerkins, sat at the bar. As with just about everyone else in Sunder, they looked like poor farmers. One man, with a leathery face, smiled, revealing his toothless gums. Another man chewed on something, probably tobacco. Eilívur never smoked, but even he knew tobacco was for smoking in pipes, not chewing raw.

Jótham motioned for the barman to bring them a drink as they sat at the table situated beside a hand-blown window wrapped in a rotting frame. Gazing back at the port docks, Eilívur could almost make out the reflection of his graying blonde hair in the glass.

“I’ve about had it with this country,” Jótham whispered as he glanced over his shoulder at the men at the bar.

The barman brought two mugs of ale and set them on the table. “You want to go back to Daecland?” Eilívur asked before taking a sip of ale. He frowned as he forced the liquid down his throat. Jótham was right. This tasted little better than bilge water. A hot cup of tea would have been nicer.

“I don’t know,” he replied with a sigh. “At least out of Llynhithe. But anyway,” he pointed to the letter again, “what have you got for me?”

“Greystrom’s arrest papers.”

Jótham raised an eye. “Lombard Greystrom? Has he been found?”

“A scout found him and his family nearly forty leagues due west of here in the Western Plains, just north of the Arglen Valley.”

“The Western Plains? We should have known.”

“We’ve always been pretty certain. But finding a homestead in the vastness of the plains isn’t easy.”

“Well, it’s about time,” Jótham replied. “This Black Horse will wish—”

Eilívur lifted a finger. “Dark Horse, you mean?”

Jótham waved his finger away. “Whatever you want to call the leaders of the Slithering,” he rolled his hand for the word. “The Slithering—”

“The Silent Hither?”

“Yes, that’s what I said.”

“Anyway,” Eilívur interrupted, “I had planned on arresting Greystrom myself, but as soon as I arrived in Llynhithe, I was asked to take on a series of training courses for the Nautical Armada, effective immediately.”

“You’re a man of many talents, aren’t you?”

Eilívur sighed. “Unfortunately. So, I must find a replacement for arresting Greystrom.”

“And that would be me?”

“I thought you would be a good fit. And you did mention that you’d like to spend some time outside of Llynhithe.”

Jótham laughed. “I’m not so sure the Western Plains were what I had in mind.” He interlocked his fingers, cracking his knuckles. “But I guess it’s better than nothing. When do I depart?”

Eilívur pushed the letter toward Jótham. “Next week.”

Jótham slid his mug out of the way and unfolded the letter, reading through its contents. “Certainly gives me enough time to prepare. Do you already have a team lined up?”

“Three men, fully armored and equipped, as well as yourself. You shouldn’t have any problems.”

“Sounds reasonable for the arrest of one man. And the family?”

Eilívur threw Jótham a stern look. “The family is to be untouched, obviously, unless you’re using self-defense.”

Jótham nodded but said nothing as he continued reading.

“That’s very important, Jótham. We don’t need the blood of women and children on our hands.”

“Of course not,” he replied, waving his hand in the air.

Eilívur sat back. “One other thing,” he said. “One of your men will be Ulnleif.”

Jótham glanced up, a cocked grin on his face.

“It’s his first mission outside of Llynhithe.”

“Look,” Jótham said, “it isn’t a secret that you’re protective of your brother. You want me to give him a special role or something?”

“No, no,” Eilívur replied. “Treat him like the others. I just want to be sure everything is done right. He’s still young.”

Jótham took a last draught of ale, tipping it up as he finished. “Don’t worry, Commander. Your brother will do fine, and we’ll have Lombard in the gallows before you get back to Everwind.”

* * *

Although the sun lay hidden behind the hills, it still managed to cast a thin light against the fleeting darkness. Lombard gazed across the rolling landscape, dotted with sparse withered plants. A sad memory lay in those hills as if they could remember when the land once stood green and lush before it faded into a barren death. But maybe it was his own conscience that made it seem that way—a reflection of his own life. It was a constant internal battle, having to fight off the temptation to wonder whether his hiding in the Western Plains was a punishment from Theos.

It had been five years since the Fellhouse Cellar was sacked by the Daecish, breaking the backbone of the Dark Horses. Landon was murdered, Galvin fled to Denhurst, and Porter and himself were hiding out in this wasteland. The Silent Hither in Everwind was now at its weakest. And as much as he didn’t want to admit it, he regretted leaving Wesley in charge. It was a foolish act of sympathy, and he should’ve put a stronger man in his place—someone who knew how to keep the Dark Horses going in Everwind—to keep the cause of the Silent Hither alive. Hopefully, Drake and Morgan would keep the poor fool straight.

Lombard couldn’t help but let out a low groan. He needed to get back to Everwind as soon as possible.

Approaching a wide depression, he knelt down. Arnon squatted beside him as he notched a cedar arrow on his bowstring. His dark brown hair, as straight as the arrow in his hand, reached down to his lower jaw. Like himself, Arnon was a Sunderian in the fullest sense. It was said that Sarig blood even ran through their clan’s veins, and he was proud of it. He pat Arnon on the back. During these early morning hunts, he had more in mind than just teaching his only son how to kill a deer. He was teaching him how to survive. How to be a Dark Horse when he was gone.

Arnon lifted his bow and drew back the bowstring, his back muscles tightening. Gazing through the tall grass, Lombard caught sight of a doe rising from her bedding, seemingly unaware of the hunters in her midst. With both eyes open, Arnon looked down the shaft of the arrow and let it go with a deep twang as it hissed through the grass and pierced the deer just behind the ribcage. Stumbling, it bolted out of the grass and over the ridgeline above. Lombard pulled the long grass he’d been chewing on from his mouth and gave Arnon a solid clap with the palm of his hand. “Barely nineteen and already surpassing your old man!”

Arnon laughed, rubbing his shoulder. “You said that last year. You sure I haven’t always been the better shot?”

Although Lombard smiled, he never could get over the softening accents of the younger generation. “Maybe, but you’ll never be stronger than me,” he replied.

Arnon began to disassemble his bow. “I wouldn’t be so sure. You’ve gotta get old at some point.”

Lombard laughed. “Not even then, boy.”

They began the steep climb up the ridge, following the blood trail. The dried grass crunched beneath their boots as dust whipped in the wind behind them.

“You ever wonder what this place might have looked like when Burgess first arrived?” Arnon asked.

“Well, being thirteen-hundred years ago, I reckon it would’ve been greener. Likely more trees, too.”

Reaching the top of the ridge, they paused as the view opened before them. The wind rushed from the west, blowing Lombard’s bearskin behind him. The Serin Sea could barely be made out as it stretched across the horizon like a thin gray thread. To the north towered the vast, impenetrable mountain range—the Great Fringe, his own people called it. Its icy jagged peaks marched from east to west, as far as he could see. There was a rumor that several new Daecish copper mines were operating nearby where the mountains plunged into the sea, and he made a point never to travel too far in that direction.

Dozens of tales about trekking parties looking for a pass through those mountains had been laid down over the ages. But as far as he knew, they never returned with success, nor without several deaths to show for it. Winds were too strong, and the natural paths went too high. The few returning survivors almost always came back with blackened toes and fingers, which would either be amputated or rot off on their own. His grandfather once told him of a man who returned sickened, mumbling and gripping his head as he coughed up blood before falling into an agonizing death.

Despite the casualties, in the early centuries, his people never gave up their search. They craved to know what secrets were hidden on the other side of those mountains. But it soon brought out the worst in them. Of course, all of that ended when the Daecish arrived from over the mountains, and the mystery turned into resentment.

Lombard shook the thoughts from his mind and looked across the ridge, following the blood trail into another holler thirty yards ahead. Next to a rotting tree lay the dying deer, caught up in briar and blackbrush.

“Why didn’t the Earlonians ever speak of why they left the Southern Kingdoms?” Arnon asked, looking south.

Lombard almost laughed. Could Arnon read his thoughts?

“Do you really think they were running away from something?”

“Aye. When Burgess and our ancestors arrived in this land, they brought with them many tales. But the one thing they swore to never talk about was why they left. I, and other like-minded folk, believe it was something they were ashamed of. Something wrong they did which they hoped to forget. Perhaps it’s why they named this land Sunder?” He tapped the side of his head. “It’s all in the name.”

They continued the trek down into the holler. As they approached the trunk, Arnon pulled the shaft of the arrow from below the ribs of the doe.

“That was a good shot,” Lombard said. “But remember you want to aim behind the shoulder.” He pointed to his chest. “Right in the heart.”

“I know how to shoot a deer,” replied Arnon shortly.

Lombard raised his eyebrows and set his boot on the trunk of the tree, crossing his thick arms.

“Look here, boy.”

Arnon swallowed as if he immediately regretted his comment.

“Don’t get put out. You’re a fine shot, but your pride gets in the way. You need to work that out of yourself.” He peered into Arnon’s eyes. “Pride ain’t strength; it’s weakness. And from it can spring forth all kinds of evil thoughts. All a prideful man shows me is that he cares too much about himself, you understand?”

“Yes, sire.”

“Your grandfather told me the same thing. See, he was a learned man and spoke wise counsel. It’s something we all have to battle.”

“Yes, sire.”

“Good, now grab your knife, and let’s clean that deer.”

By mid-day, they were welcomed by the view of their cottage, situated at the bottom of a low bluff, yet perched on its own little hill. Built of wattle and daub and topped with a thatched roof of grass and willow branches, the cottage didn’t look like much, but he built it himself, and it held strong against the changing seasons. On the west side sat a stable built of a thick layer of sod; it housed two cows, several chickens, and his own bay horse, whom he named Ansel. Out front stood a maple tree with few leaves of a dark and shriveled olive green. Lombard walked up to the front door as Arnon followed.

“Where you heading to?” Lombard asked.

Arnon groaned. “Firewood?”

“Can’t cook without it.” Lombard took the meat from Arnon and walked inside.

* * *

Setting up a hickory log, Arnon swung his ax with a great heave, splitting the log in two. The high sun helped warm the autumn air, but the occasional northern gust from the Fringe pierced through his jerkin. Just as he set up another log to split, he turned, hearing his youngest sister, Hazel, skipping through the tall grass. Her light brown hair whipped in the wind above her woolen gown.

“What’s taking you so long?” She smirked.

“Well, here.” Arnon handed her the ax. “Think you can go quicker?”

“It’s your job.” She stuck out her tongue.

“Then don’t interrupt.”

She placed her hands behind her back and dug her toe into the earth.

Arnon lifted his ax but glanced at her. “I know what you want,” he said, “but I’ve got to finish chopping this wood first.”

“Oh, but please!” she replied with wide blue eyes. Although only six, she had mastered the art of getting her way with him.

“Hazel, I really need—”

“But we ain’t played Burrow Hunt for a whole week. Pretty please?”

Arnon sighed and dropped his ax. “One quick game.”

Hazel jumped as she threw her arms in the air. “Thank you!”

Arnon turned over several logs until he found one with a clean flat top and began drawing out the lines with a piece of charcoal. “Do you have the pieces?”

Hazel searched in her pockets and pulled out a handful of dyed figurines carved from oak. She set them on the log. “I lost a couple more yesterday.”

“It’ll be all right. We’ll just have to improvise.”

As fun as this game was for him when he was younger, it was really pretty dull—just mindlessly moving pieces until one player had the opponent’s fox cornered with no way to escape. It didn’t help that Hazel still couldn’t get the rules right, so it always took longer than normal. And when she did win, which she always did because he let her, she never let him live it down.

Hazel knocked his red fox over. “Ha!” she shouted as she jumped up and jabbed a finger at him. “You lost.”

“Very good, Hazel. Now help me put the pieces away.”

Of course, she didn’t help and just ran back to the house, hollering something Arnon couldn’t understand.

With chopped logs in his hand, Arnon stepped inside the cottage and breathed in the savory smell of roasting venison and smoke. Their family home may have been small, but it had two rooms, one of which was the bedroom on the left side, with a single thick door built from oak planks. Four years ago, his father had felled that oak about a league east of there, and it took him and Arnon a dozen trips to haul it all back to the homestead. In the family room sat a little hearth in the center, with a large trestle table behind it. Arnon tossed several split logs over the hot coals and made his way to his father, who stood salting the venison.

“Give that back, Hazel!” Fleta hollered as she chased Hazel around the hearth. “That one’s mine! You’ve got your own!”

Hazel stopped and faced Fleta. Her face shone almost purple. “You tore her arm off last time!”

“Mama sewed it back on!” Fleta snapped back, snatching her doll from Hazel’s grasp. Hazel broke out in a cry.

“Girls!” called out his mother. “Outside!”

Arnon chuckled and stood beside his father. “Is the pit ready?” he asked.

“Cleaned it out this morning before we set out.” He handed Arnon a thick loin. “But we’ll need to salt and wrap the deer first.”

Arnon stepped around him, grabbing the raw meat. He brushed aside a pile of grass and broken pine needles from the counter, which he assumed was Hazel’s. Reaching between several clay jars of honey and cream, he grabbed the half-empty jar of salt. Above his head hung several bundles of rosemary and basil, which filled the corner of the room with a rich, earthy scent. “This deer will give us enough meat for a while,” Arnon said, massaging the salt into the meat.

“Enough for a few weeks, certainly,” his father replied, laying another strip of meat next to the salt jar. “On the ‘morrow at dawn, we’ll take Ansel to Rock Hill and work on our archery.”

“While riding?” he asked.

“Why else would I take Ansel? One day you’ll be the head of your kin and help lead the Silent Hither among the Dark Horses. You need to be ready.”

Arnon grinned. Nearly every day, for as long as he could remember, his father took him to Rock Hill; whether it was hunting, stalking, building, or survival, he taught him everything he knew, and his knowledge and talents seemed limitless. He happened to also be the strongest man Arnon had ever known.

Flipping over the loin, Arnon began to salt the other side until he felt a bump against his side.

“Excuse me,” came Hazel’s voice from below. She reached up over the meat, grabbing at her pile of grass and needles. “You’re getting blood on the seasoning!”

“The seasoning?” Arnon asked.

Hazel frowned and raised her grass-filled hand toward Arnon’s face. “For our pottage.” She marched toward the hearth.

Arnon glanced at his father, who only shrugged with a smile.

“Hazel!” shouted Fleta from the dining table. “Now look at what you done! You spoiled it!”

“I did not! Mama said I could season it.”

“Not with grass!”

Both Lombard and Arnon burst into laughter.

Myla hurried over to the hearth. “Hazel, dear,” she said, peering into the cooking pot as she held back her long, wavy brown hair. “Thank you very much. I’m sure it’ll taste just fine. Now do me a favor and bring in the milk from the stable. Can you do that for me?”

Hazel stuck her tongue out at Fleta before stepping outside.

“Hurry,” said Myla to Fleta. “I think we can get most of it out.”

With the sun set over the Serin Sea, Lombard lit a lantern as the family gathered around the table.

“Which story will you tell us tonight, papa?” Fleta asked, looking up from her bowl. The lantern light flickered against her green eyes. Even with her black hair tucked behind her ears, he could barely see the faint freckles dotting across her nose. When she was five, Arnon once chased her across their home in Everwind. She slipped and hit her face on the edge of a door frame. A large bump formed on the upper bridge of her nose, and it’d never gone away since. She’d always been self-conscious about it, and one time, when she and Arnon had gotten into an argument, he said she looked like a horse. It upset her so badly she didn’t speak to him for a week. Despite the passing years, he knew it had an effect on her confidence, and he’d never forgiven himself.

“How ‘bout a ballad?” Lombard asked.

Hazel grunted. “I don’t like the singing ones. They’re boring.”

“Hazel,” Myla said, “as you get older, you’ll learn to. Just listen.”

“I like ballads,” Fleta added.

Hazel shot a glare at her.

Lombard crossed his arms and leaned toward Hazel. “It’s the ballads that capture not only the past but the hearts and desires of those who shaped it. But don’t worry,” he laughed, “I’ll only sing part of one.” He then closed his eyes, and in a low, resonant voice, began to hum. His family soon joined in, and together, they sang:

I shall tell ye now a tragic tale

From Ashfirth village on the dale

In the distant kingdoms, south

By the Cymford river’s mouth

When young Brigham of Colgate

Left poor Orla to her dreadful fate

In early spring, at the break of dawn

Before the birds broke out in song

Stood young Orla with curling hair

Eyes of brown and smooth skin fair

Her dress of sage and tasseled ends

Blew against the gentle winds

On the Isen road, her people left

For the north, their hearts were set

To forget a dark and troubled past

And settle a country fair and vast

Yet by the southern river flowing

There poor Orla stood sorrowing

With cunning words and a handsome grin

Brigham had stolen her love for him

But when her womb stirred with life

He would not take her as his wife

To the north, he’d join his people

And leave her behind weak and feeble

She had no means for food or care

So she wept with a pleading prayer

No such journey could she endure

Her coming death was set and sure

Yet still, he left with a heart of ice

And spoke no more of his shame and vice

By early winter, starved and cold

She ventured north, in vain yet bold

To find that man before she died

And plead once more to be his bride

But of his fate, she could not tell

For she knew not where he dwelled

She soon grew weary with aching pain

And searched for shelter from the rain

By the road, she lay down and wept

With tears, all spent, she finally slept

Under a dying weeping willow

Her beating heart began to slow

Early one morn’, a man walked by

And saw poor Orla beneath the sky

He laid aside his hunting bow

And knelt beneath that weeping willow

In his arms, he took ahold

Her body stiffened with lifeless cold

Along the hills and through the dew

He hurried north, for her face he knew

By evening he found her family clan

And laid her body beneath that man

Who left poor Orla and child to die

As his new dame stood by his side

When Lombard finished, Arnon opened his eyes as he let his mind drift back to the room. In Everwind, at their old family home, fast-paced tunes, plucked and whistled with homemade fiddles and fifes, could keep everyone dancing for hours. But old ballads were always sung in the late night after the crowd had quieted down. His father still had an old gourd cut out and fitted with gut strings. He even had a bow made of mule’s hair to go with it. But since they left for the plains, he hardly ever played it anymore. No one even danced much either, except for maybe Fleta, when she thought no one else was looking. But even so, ballads and tales were either told or sung every night, and Lombard always insisted the whole family should sing together so that they would never forget their past.

Fleta sighed as her chin rested on her hands.

Hazel rolled her eyes. “It don’t even make sense. Why’d she go and get herself pregnant in the first place?”

Arnon burst out in an unexpected laugh.

Lombard lifted Hazel’s chin. “She made a terrible mistake and fell too easily for a worthless man who sought only to satisfy himself.”

“If you say so,” Hazel replied.

“It’s all right,” said Myla as she stood up, picking up her bowl. “We don’t all have to—” she began to say but froze at the sound of Ansel whinnying in the stable. Arnon shot a glance at his father. The whole family held their breath.

“Surely, it’s just a wolf or a—” Arnon began to say before Lombard raised his hand.

In the distance grew the thudding sound of galloping hooves.

“Someone’s coming,” Lombard said in a low voice. He slid back his chair and hurried to the door, blowing out the hanging lantern. “Arnon, go out back and stay outta sight.”

“Father, I am not going to leave—”

“Now!” he snapped.

“Listen to your father and go,” Myla whispered as she threw Arnon’s bowl in a basket.

Arnon knew why he needed to hide, but he hated the idea. He climbed through a back window and ran north against the howling wind. After ascending a steep path to the top of the bluff, he positioned himself out of sight but still had a decent view of the homestead below. Four horses galloped along the road, coming to a trot as they paused just in front of the cottage. Their uniforms looked black. Daecish.