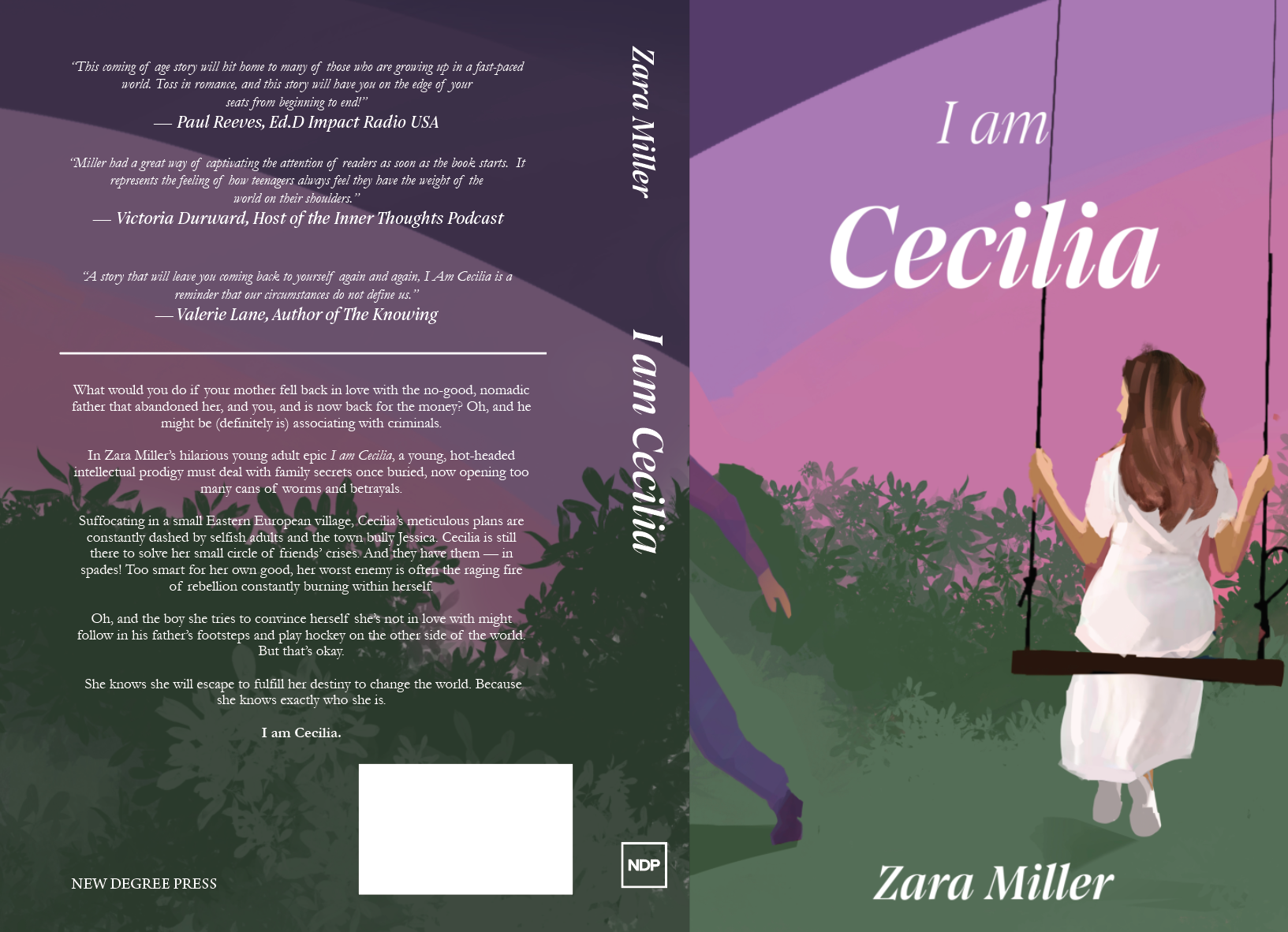

I am Cecilia

An Eastern European girl learns the ropes of life through hardships and limitations put on her by the circumstances of her birth.

Chapter 1

As the loud engine of a roaring bus with a glaring number

eighteen on its windshield lagged its way into the abandoned

bus stop, Cecilia couldn’t wait to slip in and escape

the intensifying chill of the progressing winter. She was

born in January, on a similarly unwelcoming, bitterly cold

evening. Whenever she complained about the climate, so

annoyingly characteristic for her hometown of Kosice, her

grandmother would disapprovingly shake her head and say

something witty like:

“Born in winter, hates winter—you never conform to the

obvious. Always sticking out like a sore thumb.”

Cecilia didn’t know where her mother was dragging her

or why. Still, she knew she couldn’t tolerate another Friday

evening in the company of Russian poets with her grandfather’s

tedious stories about the times he had been in the

service of the Communist Party. Oh yes, the Communists—

the only friends she was meeting in books Friday evenings.

Grandpa would always slip off into the not-so-graceful

slumber accompanied by loud snoring in the middle of painting

the picture before he managed to finish his little etude. So

Cecilia would always end up unsatisfied with bits and pieces

of unfitting edges she had to rub down and conjoin into a

puzzle that made sense in her head.

She was on page thirty-eight of the book about the Velvet

Revolution. All she had learned so far was that her home,

Slovakia, apparently used to be a slightly less miserable place

before it decided to separate its tiny, sparsely populated roots

from the Soviet Union. She wasn’t actually sure, as far as the

clarity went. Grandfather had insisted she read it, but the

book was dragging its writing as gruelingly as this bus was

rubbing its semi-inflated tires down the road.

Still, she wouldn’t let her mother leave her for yet another

weekend, to just disappear. She had tried to ask her grandparents

about Danielle’s mysterious trips, but nobody seemed to

acknowledge there were any to begin with. Both her grandma

and grandpa would wave it off, change the subject, or get so

uncomfortable the air would turn into a toxic gas. Could a

middle school principal from a well-established, respected

family like her mother be committing some ominous crime

on the weekends in her free time?

Being born stubborn and persistent, she managed to convince

her mom to take her wherever she went for those last

few weeks of November 2004.

Danielle was apprehensive about the request. Then Cecilia

activated the ultimate weapon—the upper lip pout. Danielle,

having an unhealthy soft spot for her only child, agreed to

take her.

Danielle had wanted to drive them, but Grandpa’s eyebrows

started to twitch in a nervous tic he’d get whenever

Danielle felt like unnecessarily wasting petrol or wasting

his money in any way. Perks of living with your parents in

your late thirties. Although technically, the car belonged to

Danielle. Parent logic.

Cecilia deducted that her mom’s trips were highly unappreciated

for some unknown reason. But rather than getting

through another one of Grandpa’s hissy fits, she pulled her

mom by the hand, and they set off to go by bus.

The touch of her mom’s hand, always so soothing and

comforting, sent ripples of confusion through Cecilia’s spine,

as they were climbing the impossibly steep steps her legs were

too short for, into the warmth of this conduit-in-disrepair.

Their connection, the outlandish, psychic communication

that confounded everyone who wasn’t in on it, was always

there, much like a duvet studded with juvenile images of cars

Cecilia loved so much.

After all, she was only nine, (almost ten, as she liked to

say) she was still entitled to such memorabilia.

“Dobry vecer,” Danielle greeted the uninterested bus

driver who didn’t bother to say hello back. Cecilia studied

his untidy beard and the acid blue shirt hanging on him like

a dead vine from a parched tree.

She wondered whether bus drivers looked as scruffy and

unfriendly before the Velvet Revolution. After all, it had been

exactly fifteen years since the whole separation incident. Slovakia

ought to have given its public transit officers at least a

decent uniform, she thought. Maybe then they wouldn’t look

like unpaid VH1 audience members.

She followed her mom in, fingers intertwined like vines.

Danielle uneasily wiggled through the narrow alley into the

back of the bus, away from the four dark-skinned women,

chatting in a cumbersome dialect Cecilia didn’t speak.

Cecilia felt repulsed by their bleached blonde hair and

giant hoop earrings flapping around, as the bus hit one giant

bump after another.

They finally sat down, the question burning on her

tongue, as she swayed her legs back and forth while fidgeting

in her seat, fearful to ask. She knew the route eighteen’s

stops roughly, only as far as Dandelion Street in the north

part of Kosice. Her grandpa drove her everywhere she

needed to go, and the northern part was kilometers away

from their house in the countryside called Peres, or from

her school.

Whenever she took this bus with grandma, she would

always end up in an objectionable situation—whether it

was the doctor’s office by the end of Dandelion Street or a

Catholic service in the Saint Elizabeth Cathedral. She would

always end up having to sit through a nuisance she didn’t

enjoy or understand.

The rash covers of the bus seat digging into her delicate

white stockings only reassured her that life would often

throw her into situations she would rather avoid. The itchy

skin only added to her growing anxiety.

Fear of her mother’s annoyance wasn’t what stopped her

from asking where they were headed but the dread of learning

an answer she wouldn’t like.

She preferred blissful ignorance, a silent suffering.

She was acutely aware that Jessica from school would

probably be peeling the flies off of the bus window with her

long, demonic nails, demanding an answer. But she wasn’t

Jessica.

Cecilia would never cause a public scene. She knew better

than to embarrass herself or her family like that. But the bus

either rerouted, or they finally reached the outskirts of town

near the railway station. The moment it turned right and

yawed away from the Dandelion Street allied with birches,

she no longer recognized her surroundings.

The realization of not knowing where she was made the

veiled curiosity drop like an overripe pear from a tree. If her

mother wasn’t squeezing her hand so tightly she was almost

cutting the bloodstream from flowing into her palm, she’d

be terrified.

“Where are we?” Cecilia asked, laying her hand on the

dusty window no one had probably cleaned in thirty years.

She shivered in disgust.

Her mother failed to provide an answer. Cecilia looked

down on their joined hands, admired the long elegant fingers

of her mother, the at-home-made, pink manicure on

her nails, soaking in every gentle crease, every rough fold.

Gentile hands of a teacher, a respectable, intelligent woman.

One day, her hands would grow as big and elegant as her

mother’s.

“We’re almost there.”

Cecilia’s head snapped to the side, averting her eyes and

attention from the poorly lit neighborhood filled with rusty

apartment buildings, to her mother’s loving stare—chocolate

irises drowning in a feeling, which tapped beyond Cecilia’s

vocabulary.

“Grandpa was angry,” Cecilia remarked, hoping to spark

a conversation and maybe squish her mom’s uncooperative

tendencies.

“Grandpa’s always angry,” Danielle said with trepidation.

Cecilia registered that the nervousness didn’t come as a result

of Grandpa’s aggressiveness, but she couldn’t pinpoint why

her ever-transparent mum, who she dearly admired, would

speak so unaccustomed.

Route eighteen finally came to a halt at the final stop—

Underhill. Cecilia scanned the premises. Amid mental somersaults

about her mom’s odd behavior, she failed to notice

that they were the last two people getting off the bus.

Everyone else would have either gotten off three stops

before to shop for a pepper spray, two stops before to buy

weed and coke, or one stop before to get home by walking

the Railway Bridge, effectively avoiding direct contact with

the gypsies.

Anyone who got off at the Underhill stop lived in the part

of town called “The Den of Gypsies.”

Unbeknownst to Cecilia or her comprehension of why her

mother brought her to a place that looked like it had been

ripped straight from the pages of the Oliver Twist book—she

stepped off the bus and onto a curbside ruffled with unevenly

laid concrete.

Cecilia gave her japanned shoes a distressed look. Walking

on this crooked ground would for sure tarnish the heel,

or worse, scratch the platform.

She spun in an uncoordinated pirouette to examine the

place, but the streets were silent as death.

The dawn had already come when they reached the Underhill

after more than thirty minutes of suffering through the

public transport system.

Cecilia was unsure if she believed in God, but since the

church on Sunday was mandatory, in her family anyway, she

might as well thank him for getting her out of that musty bus

alive and untouched by mold.

Cecilia scooched closer to her mother’s side, barely

reaching the hem of her black fur coat. The familiar scent, a

mix of flowers and tobacco, helped manage Cecilia’s spasm

of cluelessness.

“Come on, buttercup.”

The tension in her bones was growing exponentially as her

mother checked both sides of the road before crossing and

pulled her toward the small, ignoble-looking building with

black grating on almost every ground window.

Cecilia could hear her petticoat shuffling underneath her

velvet skirt as she forcedly towed her feet behind her.

When they crossed the road, a man came into her view,

sternly standing by the building’s main entrance with his

hands locked behind his back. Cecilia stopped in her tracks,

ready to grow roots on the spot if necessary to prevent her

mother from dragging her over to the guy currently wearing

a condescending look on his face.

“Don’t be afraid. We’ll just say hello,” Danielle reassured

her daughter. All the agitation Cecilia felt oozing from her

before was gone, replaced with excitement.

Cecilia’s pupils widened in horror. Her arm started to

hurt from being stretched out, her mother pulling in one

direction and Cecilia’s instincts in the opposite one. She

started shaking her head in panic. She overheard enough

stories from her teachers, talking about flaky mothers who

abandoned their children.

“It’s okay, Danielle,” the man spoke. Nothing about the

way he uttered those words seemed okay to Cecilia. His raspy

voice caused her stomach acid to boil and climb all the way

up to her throat. She swallowed hard, biting on her tongue

to stop herself from puking.

“Mom, who is this?” Cecilia asked, insisting on staying put.

Danielle looked over to the man for help, but he left her

hanging, asserting the upper hand by the stoic posture. He

noticed Cecilia’s jolty movements, raking her up and down

with his filthy, slighted look.

Cecilia was familiar with the dark undertone of his skin,

the same shade of creole those women had on the bus from

hell. She knew enough from her grandpa’s grotty, picturesque

descriptions to recognize a gypsy when she saw one.

“This is your dad,” Danielle said proudly. Cecilia yanked

her small hand out of Danielle’s. Her back hit someone’s side

of the car parked by the pavement. Her breathing gained an

uneven pace sickeningly fast.

Danielle gathered her in her arms, picking her up in one

swift, graceful movement. She had two options: act out, run

off, and die in the streets… or comply and regroup later.

Get ahold of yourself.

Her brain started spinning a million miles an hour. She

could recite by heart Pushkin’s work. She learned how to

divide and multiply a long time ago. This new British pop

group Blue was on the rise, and she’d memorized all the

lyrics to all their songs (in a foreign language, nonetheless). If

she ran off into the night now, she’d get murdered, or worse,

have some freakish gypsy curse put on her. Which meant,

all the talent for possibly becoming someone important one

day would go to waste.

So she gave in and let herself be carried with a quiet promise

in her heart. If everything else in this world, in this town

of torment as she loved to call it, were to lose all sense, this

would always remain true. This stranger—who her mother

called “your dad,” would forever stay just that—a stranger.

Chapter 2

Two years later

Cecilia used to think that being born to a small fortune,

accompanied by chrysanthemums on the way from the

hospital and surrounded by exploding fanfares of affection,

would set her up for a never-ending life of lottery wins,

parades without rain, and smooth slides on the slopes of

adoration.

She never realized how slippery that slope of adoration

was. Maybe money was not the root of all evil. Family dysfunction

was.

At least that’s what she had learned over the last two years,

watching the dynamic go from a pianissimo arrangement to a

Piano-Godzilla rock concert. She had been ungainly chewing

on the concept of having “a dad,” (though she never once

addressed him as such) spitting it out and putting it in her

mouth again, only to certify that the word still tasted worse

than Grandpa’s illegally distilled plum brandy. Meanwhile,

her mom blossomed like a cherry tree at a dawn of a spring

afternoon.

“The strive for greatness has ultimately destroyed him…”

She looked up curiously to check whether Miss Francisci,

(or Miss Wet T-shirt, as Cecilia secretly nicknamed

her) still opaquely mumbled through her history lecture or

finally picked up the tempo. The Slovak national emblem, a

double white-red-blue cross skewered on the highest hill out

of the triple mountain chain, lingered on a dusty portrait

behind her head.

Now that she was older, she understood the crippling

obsession these people of Kosice had with God. She never

equated or identified with it.

This town, whose only excitement occurred during May

when the world hockey championship ravaged the streets

with enthusiasm and patriotic spirit, was otherwise so freaking

boring Cecilia felt like stabbing herself with a hot rod

most days.

No wonder folks turned to faith for help. If she believed in

God (now being twelve and having read through the Scripture,

she concluded with certainty she didn’t), she would also

pray three times a day for something to happen in this town.

She longed for drama to disrupt her routine. She ached to

transform into a heroine from those simplistic Latino stories

to pump a new dose of adrenaline into her veins.

“His quest for glory, and riches, it all came down to a halt

eventually…”

And every weekend, when Danielle left for the Underhill,

an invisible thread that attached her to her daughter thinned

down tremendously.

This isn’t forever, she reminded herself patiently, as she

crafted an elegant D with a heavy, lopsided tail in her notebook,

where scribbles about Alexander the Great were supposed

to be. She still wasn’t sure if the D stood for Danielle,

Daemon, or Dysfunction.

She was trapped in a family threesome with her parents

and their unfinished business from the times the Backstreet

Boys were still making hits.