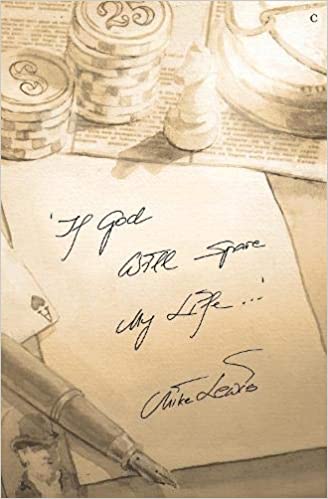

'If God Will Spare My Life...'

‘IF GOD WILL SPARE MY LIFE…’

By Mike Lewis

CHAPTER ONE

Fort Abram Lincon

Dakoter Ter

June 15/76

Deer Will

Wish I cud says I was doin okay but in trooth am findin it real hard.

The day you rode outta heer in that missed we was stood thar wavin an it luked like you solder boys was ridin high into them clouds leastways thats how it luked to us.

Nefer seen nutin like it afore.

Sum folk reckoned twas a bad sign an that nun of you boys was efer comin back alife.

Thar I was wiv an offisers wife aweepin and awailin on ma shoulder an I was stood thar feelin just as bad

1.

Haverfordwest

April 28, 1904

Arthur Nicholas glanced up from his desk as the sound of parting voices signalled Reginald Eaton had opened his office door. Having paused in the doorway to shake his master's hand, two visitors duly emerged, the elder catching Arthur's inquisitive eye.

Living in the port of Fishguard, in the south-west corner of Wales, the young apprentice solicitor immediately recognised the man as Gwynne Austin Roberts, well-known and highly-respected manager of the town's Lloyds Bank in West Street. The face of his tall, angular companion also looked familiar, although Arthur could not quite place it. The second visitor bore the weathered complexion of a man of the Pembrokeshire soil and when they shook hands moments later Arthur noted he bore the callouses of one too.

“Well now, young Arthur, I'd clean forgotten that this was where you worked,” said Mr Roberts, a pleasant, avuncular man in his mid-forties, extending his hand. “This young fellow, Henry,” he said, turning to the other man, “is Mr Arthur Nicholas, the son of a very dear long-time friend of mine, Charles Nicholas, the late blacksmith from Dinas Cross. Arthur, please allow me to introduce you to Henry Rees, of Carne Farm, Goodwick.” The pair shook hands and nodded at one another.

Turning to Rees, Roberts stroked his chin thoughtfully and said: “Come to think of it, it's a damn shame Charles is no longer around to help us in our quest. He knew cousin William well. Shoed his horses on many an occasion and, I daresay, probably had a hand in many of Will's little japes as well!” Rees smiled knowingly and nodded.

The trio made small talk for a few moments, before the two men turned to depart for the town’s railway station. “Please be mindful to remember me to your mother,” Roberts told Arthur, returning a bowler hat to his greying head as the two visitors took their leave.

Arthur was 21 years old and had been working in the Haverfordwest office of Eaton Evans and Williams for five years. Lately, he'd been finding the work, or at least the work Mr Eaton passed his way, particularly humdrum and had even started to question whether life as a solicitor was truly for him.

Working in a stuffy office in which a smoky coal fire needed constant tending left Arthur with a splitting headache most days . And even after five years he possessed the uncomfortable feeling that he did not truly fit in.

His father had worked as a blacksmith all his life and Arthur was becoming more and more convinced he too would be better suited to a manual occupation. And preferably one in the open air to boot. Yet his parents had been so thrilled when he landed a job which they felt would be a significant step up the social ladder that he felt compelled to make the most of it.

The day a letter arrived informing him he was being offered a position saw his mum proudly conveying the news to every soul in Dinas Cross. She had even told Evan Williams, the one-time saddler, though he was as deaf as a post and in a somewhat confused frame of mind. The look in the poor man’s drowned eyes as she relayed her news suggested he was having a devil of a job trying to remember who he himself was, let alone some young chap called Arthur Nicholas.

Two minutes later Arthur was summoned by the head solicitor into what staff termed 'the inner sanctum'. “Take a seat, will you, lad?” said Eaton briskly, clearly in a business-like mood. “I gather you were a bit on the late side this morning. Least said about that the better, I suppose, but I have every confidence,” he continued, as Arthur slid awkwardly into a chair on the opposite side of Eaton’s desk, “that this little oversight will not be repeated.”

2.

“Terribly sorry, sir, I'm afraid the train was delayed by...” Arthur's blurted response was cut short by a deft wave of Eaton's hand. “Spare me the details, dear boy, least said, soonest mended,” he said airily, “I have an important assignment I'd like you to tackle and a somewhat unusual one at that. And the fact that you hail from that charming village of Dinas Cross suggests to me that you are eminently qualified for the task.”

Arthur was both puzzled and curious at this intriguing disclosure. “Assignment, sir? Of what precise nature, exactly?” he enquired.

Sliding a file of papers across the desk towards him, Eaton explained, in his usual clipped manner, that his two visitors were the will executors of one John Clement James, a cousin of Roberts, who had died in Swansea of consumption, that hideous wasting disease, aged 52 in May of the previous year.

Arthur had vaguely known the gentleman farmer who had owned the large farm of Llanwnwr, out on the rugged peninsula of Strumble Head, which protruded like a giant's muscled bicep into Cardigan Bay. A couple of years before, James had officiated the first football match ever held between Goodwick Welsh and Fishguard Rovers, for whom Arthur played as a defender.

Despite being billed as a 'friendly', and the County Echo's pre-match entreaties for 'brotherly love to prevail', the match had turned into something of a bloodbath and Arthur still bore the scars on his legs to prove it. There had been precious little brotherly love displayed on the pitch that day, he recalled ruefully. In fact, Mr James’s whistle had sounded so frequently that it had been a wonder the somewhat breathless, ruddy-faced fellow had not run out of puff.

Eaton went on to explain that, as John Clement James had died a bachelor, it was imperative to establish whether there were any living heirs to the farm before it was sold at auction.

“Four of John Clement James' five brothers are known to be deceased,” he went on. “However, there are question marks over the fate of the fifth.” “How come, sir?” Arthur wanted to know.

Eaton lit a cigar and, rising from his chair, slowly began to pace around the office. “As things stand, William Batine James, possibly the sole surviving brother of the late John Clement James, stands to inherit one of the finest farms in the north of Pembrokeshire,” he explained. “T'is a property I wouldn't mind getting my hands on myself, if truth be told.

“Trouble is, no-one in these parts has seen hide nor hair of the aforementioned William Batine James for well over thirty years. Through letters John Clement James left behind,” he said, indicating the file in front of Arthur, “we know his brother travelled to Canada in the March of 1871 and from there to the United States a couple of years later. The last missive John Clement James received came from a town called Opelika, Alabama, down in the Deep South of the country.”

“Do we know what occupation William James pursued out there, sir?” asked Arthur. Eaton flopped down opposite him with a weary sigh and shook his snowy head.

“Unfortunately not,” came the reply. “Infuriatingly, from our point of view, the letters he left behind tell us precious little about Mr James' activities, let alone his current whereabouts if, that is, the gentleman is still in the land of the living. William James would only be in his mid-fifties by now, however, so it is perfectly feasible he is out there somewhere. The question is where exactly and how the deuce do we set about finding him?”

“Is there any firm evidence that James is in fact deceased?” queried Arthur. “The mere fact he has not been heard of in over thirty years suggests to my mind that he might well be.”

3.

Eaton drew long and hard on his cigar before tilting his head back and releasing a stream of blue smoke into the veritable fog already suspended over his desk.

“Well, John Clement told his will executors that he'd received notification of his brother's death many, many years ago. He said one of the letters he dispatched to America was returned with the word 'deceased' written thereon. Suffice to say, the letter imparting that information could not be found among his private papers, so as things stand we simply cannot verify William Batine James's reported demise.

“Of course...” Eaton looked at Arthur and smiled, “if one were of a cynical nature one could argue it would have been in John Clement's interests to put it about that his elder brother was no more. John Clement stood to inherit Llanwnwr, after all, and it could be argued that the last thing he'd have wanted prior to being handed the keys to that fine property was brother William turning up from North America unannounced and somewhat queering his pitch, shall we say?

Eaton took another drag on his cigar. “John Clement, a long-time sufferer of poor health, spent his final years living out there on Strumble,” he went on, as Arthur swallowed hard in an attempt to stave off a coughing fit. Prior to that I gather he lived and worked in Swansea for a time. On his death he left a considerable amount of money to the Welsh Terrier Club, of Swansea, but no apparent heirs to Llanwnwr, which his family have owned for well over a century.

“Terrier club? A somewhat unusual beneficiary, I’m sure you’ll agree, sir,” observed Arthur.

“The gentleman evidently loved his dogs,” Eaton nodded his head and rolled his eyes. “I have it on good authority,” he continued in a bored tone of voice, “that the late Mr James was never happier than when holding court on the merits and intricacies of the breed to anyone unfortunate enough to be within earshot; hence his decision to donate to the Welsh Terrier Club a generous sum of money. Each to his own, I suppose.”

Eaton sat back in his chair and frowned. “Brother William remains a true mystery man, however. We don’t even have so much as a photograph of the fellow to go on. Apparently left for Canada in considerable haste by all accounts, which makes me wonder whether he may have committed some form of foul play.

“The James family were respectable, God-fearing farmers who were well known in Fishguard and Dinas, yet I’m told seemed to suffer some form of collective amnesia whenever the name of William Batine James popped up. They didn’t speak ill of the fellow, you understand; just didn’t speak of him at all,” Eaton again shook his head, perplexed. “What particular skeleton did this chap have in his cupboard, I wonder?” he said, examining his well-manicured nails. “Gwynne Austin Roberts, who was very young when James departed for Canada, suspects he was, as he put it, the black sheep of the family who farmed Pencnwc on the Cardigan side of Dinas Cross, by the way.”

Having grown up in the village, Arthur was well familiar with Pencnwc, a large farm perched above the Gideon chapel in the shadow of Dinas Mountain. As a small boy he and his friends had habitually collected conkers in its nearby woods whilst running the gauntlet of the reclusive and belligerent elderly farmer who lived alone there. His angry shouts as they scampered back towards the village across his fields, pockets bulging with conkers, had been an entertaining part of such youthful adventures. The fact Arthur had no recollection of the James family was unsurprising as he would duly establish that had vacated the farm a good twenty years before he was born.

4.

Eaton removed his cigar and stabbed a nicotine-stained forefinger at Arthur. “So this is where you come in, young man. I want you to make inquiries into the possible whereabouts of William Batine James, or at the very least seek to establish whether he still walks the Earth.

“Unless we can learn his ultimate fate, or at least be seen to have moved Heaven and Earth in order to try and establish the full facts, the future of Llanwnwr will technically remain unresolved, which is obviously the last thing his brother’s will executors want.

“You're a smart fellow, Arthur, with a good head on your shoulders, who to some degree reminds me of my younger self,” Eaton beamed at his young charge, “I have no doubt that you will excel at a little Sherlock Holmes-type of detection and, should you be successful,” he paused, squinting slyly at the apprentice, “why, I might even be minded to rustle up a little pay rise, plus...” he continued, raising his voice a couple of octaves, “I could even be prepared to overlook the fact that you rolled up for work well over an hour late this morning looking like a man who'd slept in a hedge!”

Eaton returned the cigar to his mouth with a curt nod of his head.

“Yes sir, thank you sir, you can rely on me sir,” stammered Arthur. “Please rest assured that I will leave no stone unturned. I'm more than happy to accept the challenge and shall begin my quest for William Batine James forthwith. And I can assure you, Mr Eaton, that you will not find me wanting!”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

5.

“Call me Ishmael…

“Look, having arrived at my destination a tad sooner than expected I'm happy to give full chapter and verse. And I won't take offence at being deemed guilty of spinning a web of falsehoods ‘cos, if truth be told, I can scarce make head nor tail of it all myself...”

Powder River Depot, Montana Territory, June 8, 1876; (17 days out from the Battle of the Little Bighorn)

“Huna blentyn ar fy mynwes Clyd a chynnes ydyw hon; Breichiau mam sy'n dynn amdanat, Cariad mam sy dan fy mron; Ni chaiff dim amharu'th gyntyn, Ni wna...”

“Letter for Sgt William B James!”

When I think back on those distant days of childhood I remember the toy sailor, wooden rocking horse, tatty tin soldiers with flaking paint, the Noak's Ark, chipped painting of Lord Palmerston and vast, blue-patterned bedspread.

But what I can't recall for the life of me is the name of that sweet Welsh lullaby Mother would sing softly whilst tucking us all in...

Whatever it was called was cut short by that crude shout exploding in my head. It caused me to tear my heavy eyelids open and sit bolt upright in my blanket with a start, right hand fumbling for the Colt.

The piercing cry seemed so loud and so near that I'd have sworn someone was sat plumb in the middle of that foul-smelling US Army tent with us. I stayed motionless for a jiffy, blinking foolishly at the cream canvas like an owl shaken awake on its roost, slowly taking stock of all around me.

All I could hear over Ogden's snores was the buzz of those infernal mozzies that made camp life such a misery, the chomping of the horses and the picket's call of “All is well!” from way over yonder. As I came to my senses I lay back with a weary sigh as it dawned on me where I was. The letter I yearned for so badly existed only in my dreams.

They say the howl of a coyote is the most lonesome sound out on the prairie; a sound that penetrates right into the heart of a fellow's soul. Lying in our three-man pup tent next to the gurgling Powder I wasn't about to argue. The critter was perhaps a good few miles distant, yet his mournful refrain steadfastly kept me from returning to my slumber.

That and Ogden's snoring which seemed to have gotten worse in the three weeks since we'd ridden out of Fort Abraham Lincoln past lines of weeping soldier wives as Custer's band played 'The Girl I Left Behind Me'. T'is queer how a man can feel so alone when he has 1,200 men of war and hundreds of horses and mules all seeking to rest their weary heads around him.

All the boys could sense a battle looming even if it went largely unspoken. We enlisted men were never told when or where we were going; those officers would just say they'd tell us once we'd gotten there. Yet being soldiers we could feel something was coming in our bones.

The same kind of feeling you get afore a prairie storm blows up. Fellows who talk much go real quiet and those who don't normally say boo to a goose just won't hold their tongues.

6.

We knew not even those will o' the wisp Indians couldn’t run and hide forever and although we'd reckoned on finding them in the Badlands a week or so back there was now barely a fellow among us who didn't anticipate a pretty hot fight and that old Chief Sitting Bull would think he was in the middle of a hornets' nest once the fighting Seventh caught up with him.