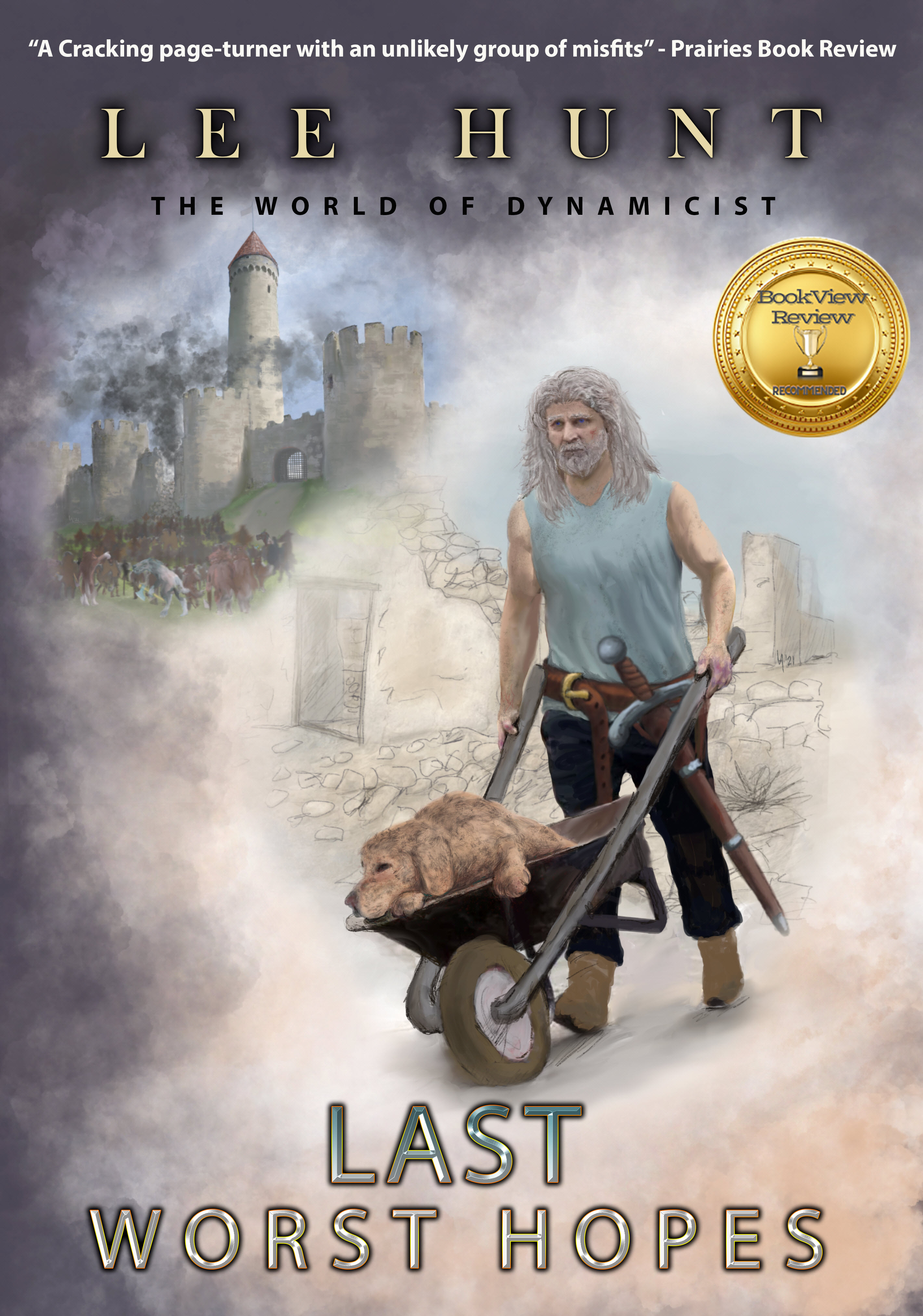

Last Worst Hopes

Prologue. From the Library of Lady Koria Valcourt

Few events have garnered more historical attention than those of the Methueyn War. And fewer still are less understood.

Most scholars have focused on the life of Nehring Ardgour, undoubtedly the principal player in these events. He was the most powerful wizard in history, but perhaps the least human human being there has ever been. As a child, he nearly succeeded in stealing the Methueyn Bridge, that unfathomable device that allows the Methueyn Knights to share heavenly communion and power with the eight Methueyn Angels in Elysium. While still only a young man, he invaded the northern half of Engevelen and held it for a generation, mining it for the secret elements he needed to build a doorway into another, better world. Entire wings of libraries have been devoted to speculating on why he used his hard-fought power to open a door to hell instead, and bring forth the demons Skoll and Hati, and the hordes of skolves that served them. Ultimately, the why of it does not matter.

Other historians have focused on the Methueyn Order, the holy knights connected to heaven, and the reasons that they alone, at first, went to war with Ardgour. And why, acting alone, they spent the lives of their lesser order, the Deladieyr Knights, and the squires to those knights. But for all their power, the Methueyn Knights are an uninteresting subject, for they lacked the ability to change or grow. Theirs was the curse of too much confidence and too singular a focus.

As the war ground on, all these great heroes fell, and in the end, it was a group of misfits and castoffs—my arrogant and literal-minded ancestor among them—who made the difference. None of them seemed adequate to the challenge, but when everyone else was gone or had failed, these last hopes found their purpose.

Only now, two hundred and fifty years after their struggle, have we finished what they started and reclaimed the wilderness and the Bridge that were lost at the end of their war. So many of us died getting here. Thinking of my lost friends, I finally understand how those last worst hopes must have felt, retreating victorious from the rubble of all they knew.

Chapter One. Sleep

Hoping to find sleep, I count my crimes against humanity. Yes, most people count innocuous things like sheep, but I want to tally my crimes and tell myself that I am still human. Many would think that counting the harrowing acts that led to so much misery and death would do the opposite of putting me to sleep, but my strategy works because I did not actually commit the crimes. I am a politician, a diplomat; I do not do the deeds, I enable them, apologize for them if necessary, deny them when I can. In trying to find both my own last best vestiges of humanity and any sleep that might be available, a narrative of honesty surely could not hurt.

What also helps is that I have not been personally involved in any of it. I had not been responsible for talking the Methueyn Knights out of hunting down and killing Nehring when he attempted to steal the Methueyn Bridge as a child. My predecessor had successfully argued for mercy for the folly of the young. That had been a great victory of diplomacy, especially given that hindsight proved the event to have been but a small taste of things to come.

The invasion of Engevelen by a now adult Nehring Ardgour was also before my time. That awful crime stole half of the greatest and most respected country in the world, and at the price of only a little slaughter, though a lot of slavery. Keeping that malfeasance from turning into an uncontrollable war had been a major feat of diplomacy by my predecessor. Promises to never do it again had deescalated the conflict and enabled everyone to sleep better.

Yes, this counting is good for sleep.

But on my side of the ledger are the colossal issues of the present day. The widespread slavery of Ardgour’s people for his … public works projects. An entire generation has been eroded digging in the earth for those inscrutable purposes. Misinformation proved to be the best tool to shovel over that ongoing and arcane awfulness. The summoning of the demons Skoll and Hati was, of course, a far worse problem to deal with. Every wizard across the planet felt the horror of it, but I assured everyone that the two demons would go straight back to hell. I guaranteed it.

But they did not go back.

Instead, Nehring only compounded the horror, bringing across, in their tens of thousands, those devil-like beings we call skolves. Not as bad as Skoll and Hati, but unequivocally bad nonetheless, indubitably an assault on all of mankind. I stood in front of each nation and called it an “accident.” It might even have been one. As previously noted, I do not know these things. I do not do the deed, I obfuscate it.

I may have failed to talk the Methueyn Knights out of declaring war on Ardgour, starting the so-called Methueyn War, but I did succeed in discouraging the other nations from immediately joining in. Now, a few short years later, the war has grown larger. The remains of Engevelen have joined the Methueyn Knights in fighting Nehring Ardgour and his demons. Engevelen by itself proved too weak. Matters had become so bad that the Methueyn Treaty was invoked, and certain forces from each member state joined the war. That was a diplomatic loss for me.

Those were my contributions to the current state of the world. The major ones, anyway. Now I could sleep. It used to be, when I was a little girl, that I dreamt of being a hero. Perhaps, having recounted my crimes, I could now have that dream again.

I may not deserve it, but even a ruined and compromised politician can dream of a better world, one of beauty, joy, hope, and happiness, of the implausible possibility of virtue recovered and heroism rediscovered. However much I had let myself—well, the world—down in waking life, there was always the slim possibility of finding the ephemeral buried treasure of blessed delusion in the world of dreams. Such a fantasy almost never happened. And I deserved the nightmares, after all. Yet, as I descended deeper into unconsciousness tonight, it seemed that this childhood dream would be my unearned reward. I could almost see the little girl of my youth once more speaking truth in the face of lies and entrenched power. There she was. The hero!

But then, like a fickle wind, something on the boundaries of my dream abruptly changed. The little girl disappeared.

Something came for me, for the adult me, the frightened, morally compromised woman of the world me. The criminal against truth, me. Something came for that me, the coward. Something that would require all the integrity that I had already dropped into the refuse heap of my adolescence.

Even if I had not so easily and so fully discarded them, dreams of heroism and a better world would have been no substitute at all for armor, no defense. These delusions meant nothing to what approached. The darkness did not protect me, nor did the veil of sleep, the solid barrier of three-foot-thick cold stone walls, or the alert guards in colder steel who patrolled the halls. Not one of those things mattered at all to what came. With a bare flicker of sound and a complete absence of light, a presence spilt reality and manifested itself at the foot of my bed. A cold intelligence bore down upon me, heavy, unsympathetic, intruding upon my mind as suddenly and unequivocally as it had appeared in my bedroom.

Eyes still closed, I shrieked.

An electric shock made me shudder and involuntarily open my eyes. A darkness flickered at the foot of my bed, somehow opaquer than the rest of the night. Being aware of it was a thing like proprioception, for there was no light at all in the windowless tower, no real difference in the darkness in so far as darkness has anything to do with light. There was a sound though … like a flame might cause … like angry grease burning in a too-hot fire. I had encountered Nimrheal twice now, flickering disturbingly like some murderous and unpredictable black flame, shrieking at painful volume, poorly bound to reality, a violent best representation of something undefinable and outside our world. This presence reminded me too much of the demon. Far too much. Perhaps twenty years spent evading Nimrheal had somehow transformed Nehring Ardgour into a being very like the demon itself.

Garragorah.

It is a horrible new thing, the sound of Ardgour’s voice. It no longer sounds human. It reverberates—crisp but resonating—like something spoken in some great cathedral instead of my bedroom; loud, deep, and intimidating, as if it was from a giant. I feel Madalise go stiff beside me.

She knows not to open her eyes and look for whatever mouth could shape such a sound. There is no mouth to be seen anyway. If his lips move, they are impossible to resolve among the layers of black, flickering shadows. I am not sure if the apparition before me is really Nehring Ardgour, or better put, fully Nehring Ardgour. My lord would have hated the smells of a bedroom, he would not have come here in the flesh. The very earthiness of the place would have offended him, the animal odors, the sweat, the bad breath of the mouth breather. He hated any reminder of our ungodly limitations such as the need for food, sleep, or the release of sex. Ardgour hated the animal nature of humankind, hated humans and their crude coarseness. And since the many battles with Nimrheal, the inexorable loss of the Vymyty—since both Volsang and the Shining Knight of Vercors began stalking him at each hidden fortress, mine, or laboratory—Nehring Ardgour had become a presence unfirmly rooted in time or space. Or in humanity. He seemed to have moved beyond all that now, but the question of what stood before me, specter, man, or something else, did nothing to put me at ease.

“My lord?” I say after licking my lips and reaching over to pull the thick, soft bedcovers up and over Madalise’s head. The blanket is only a pretend protection, but I try to fool myself that it is worth something, and that under the too-thin cover of the thick duvet, she will not feel the sick pressure of Nehring Ardgour’s mind upon hers.

You must go to Engevelen, to the Council of Knights who meet there to decide how best to kill me.

“What?” I ask, dumbfounded. It is an impossible, a ridiculous request, considering our war with Engevelen and the Knights.

Tell them they must take up their bridge to heaven, the thing they call the Bifrost, and bring it to me.

I speak before sense can hold me mute. “But my lord, you tried to steal the Bifrost.” And that was just the start in a sleep-counting-long list of atrocities that Ardgour—we—have committed. In every meaningful way, we have utterly betrayed everyone. We have shown every nation on earth, Engevelen most of all, that we are not to be trusted.

Yes. You must obtain through words what have I failed to take by force.

The incongruity of his orders had me flummoxed, caught between mortal terror for myself and for Madalise, stiff and shaking under the duvet, in utter, unaccustomed confusion over this change in plans. I had thought we were almost ready to execute Nehring’s great scheme, the work of a generation, his apparatus. That I did not know what it was supposed to do was not the point. I understood that he had a plan. This was not it.

“But, my lord,” I say like someone stupid enough to volunteer for her own funeral, “this was not the plan.”

The day had finally come round once more when I was so stunned that I actually gave utterance to what I thought. Since I had been a heroically dreaming child, no one had ever observed such a wonder. It is, after all, a poor ambassador who indulgences her own personal truths.

The other Lords of Novgoreyl have turned against us.

My stomach falls.

No one is with us. No human, anyway. At least we still have Skoll, Hati, and the skolves.

Not a preferable situation, but that infernal army might still be enough.

Skoll and Hati have broken their leash.

“When?”

Some time ago. That news, I suppressed here.

Knights in heaven. Lie on my face, Leylah.

A thought flashes like lightning. The Renet! This is why they attacked.

Fuck. Fuckity fuck fuck. Fuck.

Pull yourself together, woman! I stifle a hysterical, what could have been a fatal, laugh and tell myself this day has been coming ever since the demons arrived. In better, more human days, Nehring had explained how it could happen, but he had planned to start his apparatus before the demons realized the limitations of his power over them.

“So … you have a new plan, then?”

There is no answer. Nehring Ardgour has a limited patience for stupid questions. I need to pull myself together and put my negotiator’s face on.

“May I know your mind, Lord?”

How could you possibly know my mind? Has your consciousness travelled to other worlds, seen gods and monsters, looked through the fabric of reality to the modulii that constrain all possibility? Have you broken the inventive barrier and tripped Nimrheal’s interdiction? I alone have done it and lived. Not once, but eights of times. You may not know my mind. You cannot.

And what on knights’ earth or Nimrheal’s hell do I say to that?

A moment of silence follows as I attempt to answer my own question. I wish it had been a rhetorical one, but I do need an answer. For a few short, long moments, his shadow burns the darkness, crackling disturbingly in the night.

“My lord,” I begin again, filling the silence, forming a tremulous shield of words against his dark and menacing presence, “I only wish to be able to convince them to do what you say and come here.” I risked a look into the dark shadows where Nehring Ardgour’s eyes should have been. That was a mistake. Looking into a bottomless nullity only enhances the feeling of otherness. Looking at the flickering nightmare also encourages the hysteria to return. Insane, suicidal laughter attempts to jump ship from my mouth. I bite down on it, bite my own lip until I taste the copper of blood, before I dare continue speaking. “After all that’s happened, we must gain their trust.”

How would knowing the truth gain anyone’s trust?

I close my eyes, looking for my center, trying to summon wisdom. “Perhaps we have come to the unlikely point where only truth will serve.”

Who understands truth? Deep below this room, down there in the darkened gaol under your castle, a poisonous transformation is happening. It is the splitting of nature, an assault on what you know of fragile matter.

It was this fragile matter that had done in the Shining Knight, had driven off Volsang for a time. “The mine?” I say, thinking of the mirrored breastplate burning and the quiet voice screaming to the heavens.

One of the many mines.

One of the many crimes against humanity that I had facilitated. Many have been consumed by what we have mined. “I don’t understand, my lord.”

That is the problem. Your thinking is insufficient to grasp that one piece of knowledge. One of many pieces. If you cannot speak to this one small thing, how can you possibly understand the breadth of what is happening, let alone describe it accurately? You are an ambassador, a paper-thin politician, a mouthpiece skilled in eloquence, lacking in deep knowledge. How can you speak to necessity, describe its horror, entreat these others to aid in it?

Sure, let’s just mangle the messenger, flagellate her with philosophy, injure her with her inadequacy!

That thought comes from the part of me that became unstuck from reason the instant Ardgour materialized in my bedroom. Insane though it might be, as reckless, poisonous, and dangerous as it is, it is the only truthful voice left in my mind. It is the part of me that wonders if my demon-summoning lord has become a demon himself, or is perhaps something even worse.

Fuck, I cannot listen to that voice. I need to lie. I need to listen to the part of me that wants to survive. I need to speak carefully, like an adult, not truthfully like a child.

But I also need something to work with. “And yet you ask me to do this.”

I tell you to do it.

Such is the hell of my life. I make another attempt at reason. “If I am . . . limited, I am limited like them. They won’t come unless they trust that it will be in their best interest. I will need some kind of story for them.”

A yarn.

“Yes,” I agreed. Please give me something. “A story. What can I tell them, Lord, that will persuade them to trust your request?”

My request? It is no request. Tell them that.

“My lord,” I say, ransacking my cowardice for courage, “that will not be effective. The Methueyn Knights hate you for the skolves. They make war on you for Skoll and Hati.” I swallow. “They will not take your orders.”

Then think on what a generation of my people have done here. Let no ignorance or incapacity stand in your way. Spin your yarn.

Ask Paige - Team Assistant

Ask Paige - Team Assistant