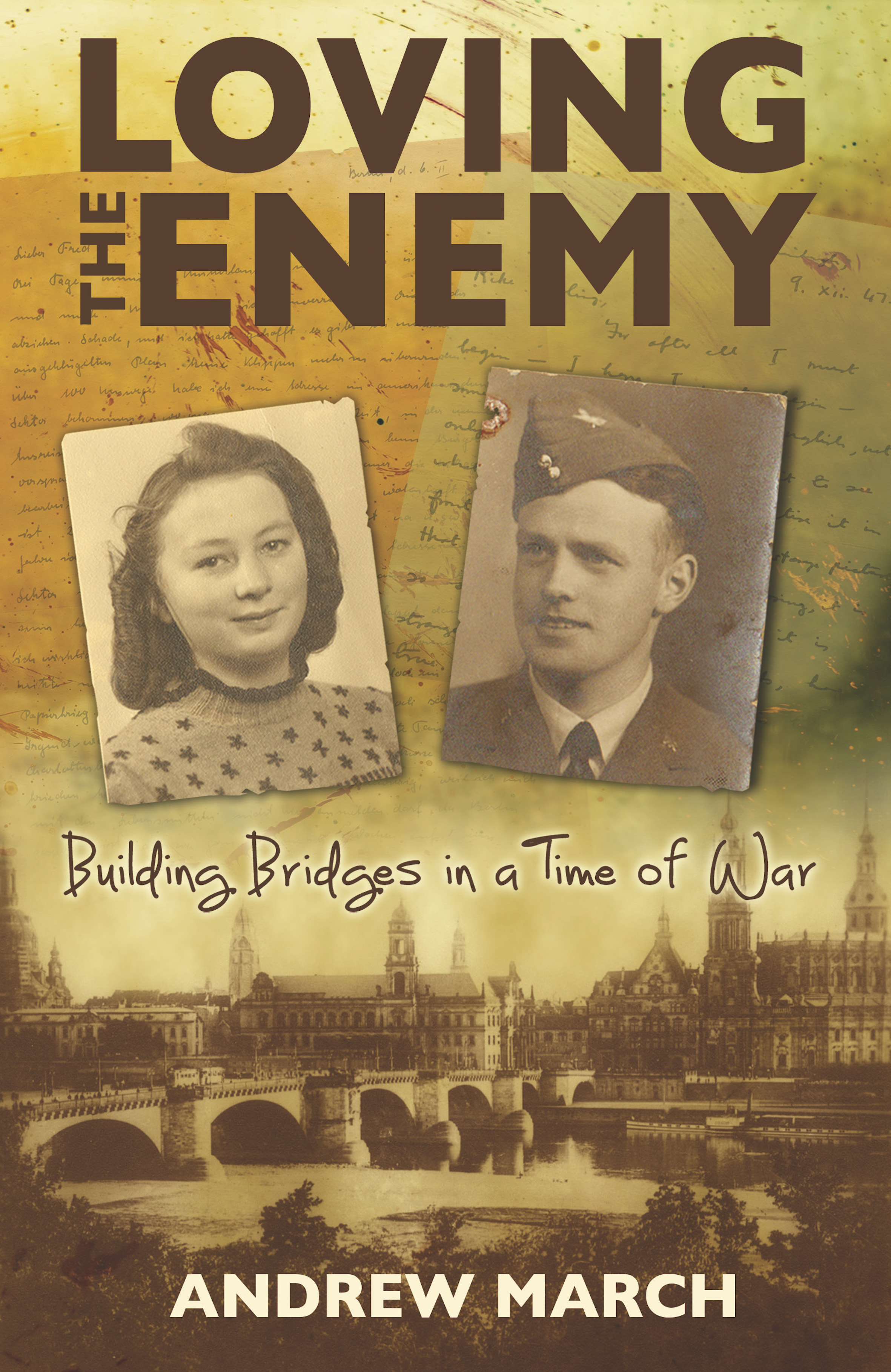

Loving the Enemy - building bridges in a time of war

It was May 1934. Frederick William Clayton, small, slight with sharp blue eyes emphasised by a splash of jet-black hair, was twenty, a year younger than the rest of his cohort, when he completed his final paper for his undergraduate degree in Classics. He already knew what his next challenge would be whilst waiting for his Masters to begin in the autumn; he skirted round the freshly mown lawn, flicking through the pages of the German textbook, delicately balanced on a dictionary he was cradling in his arms. Here was an opportunity to get to grips with another language and culture, to discover new worlds, to read the works of Goethe, Hegel, Schleiermacher, and other Romantics in their native tongue. Here was an opportunity too to gain an understanding of this new movement, this revolution, spreading like a disease across Germany. Little did he know this decision would shape the course of his life.

Fred had begun life at King’s College, Cambridge in 1931 and his time there had coincided with an increase in political tension all around a world still reeling from the impact of the Great War and from the Great Depression. In Germany the wounds and recriminations still festered, leading to the rise to power of Adolf Hitler, who promised to restore Germany’s national dignity. Meanwhile, in the East, a Red Beast rose up, with Soviet Russia claiming that it was the only country that had rid itself of the war-mongering clique that had been responsible for the Great War in the first place. There was no escape from these issues, not in the debating chambers of Oxford or Cambridge, whether in the dining hall, in fellows’ rooms over lunch or tea, or on the lawns, where the rise of National Socialism and Communism and their various merits were topics of hot debate. Indeed, while the Oxford Union voted in February 1933 to ‘never again fight for King and Country’ causing uproar in the national newspapers, with the Daily Telegraph announcing, ‘DISLOYALTY AT OXFORD: GESTURE TOWARDS THE REDS’, a substantial number in Cambridge turned to Communism as the only safeguard of peace.

In contrast to his peers at King’s and the other colleges in Cambridge, who hailed from Eton and other public schools, Fred had been brought up in a semi-detached house in Mossley Hill, on the outskirts of Liverpool and educated in a state grammar school, the Liverpool Collegiate School. Whilst his peers’ relatives were overwhelmingly wealthy, his father, William, was a headmaster of a small village school near Liverpool, his mother, Gertrude Alison, was a housewife and among his relatives were post-office workers and shopkeepers. Fred’s older brother, Don had been prevented from pursuing his own dreams of university because his parents were unable to afford the costs involved, instead working for the Pioneer Assurance Company in the city. Fred could hide all this, pretend he wasn’t so different, until he opened his mouth. His Scouse accent gave the game away. At King’s he was a fish out of water, a novelty and, he suspected, a figure of fun. He hadn’t been entirely happy at first, being made aware of his Lancashire accent and his being ‘different’, even by people meaning to be kind. Someone even suggested he change his name – people called Fred didn’t go to King’s – Francis or Hilary (weren’t those girls’ names?) were proposed as acceptable substitutes.

It had been a heady time, socially as well as academically. Despite his initial feelings about not fitting in, thanks to his precocious academic brilliance, the red carpet was laid out for him and he was welcomed into the cabals of the intellectual elite. Here he made good friends, people to whom he was passionately attached. He dined in refined company such as the world-renowned economist, Maynard Keynes, and literary giants, E M Forster and T S Eliot. Keynes had invited him to dinner once and lunch twice in his rooms in Webb’s Court, which had oak panelled walls dominated by eight extraordinary murals by painters Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell depicting the muses of arts and sciences.

Fred wasn’t much of an arts aficionado himself, but he knew that Keynes was and had the good sense to ask about the work that Keynes himself had commissioned. At the second lunch, Keynes had invited Fred along with Basil Willey, an English Literature fellow of Pembroke College and T S Eliot. Though he had been greatly anticipating socialising with someone so renowned, Fred was disappointed; Eliot hardly said a word, which Fred had thought strange, only to learn later that this was not uncommon. This particular lunch was turning out to be an excruciatingly awkward social occasion and Willey managed to escape early. In desperation, Keynes turned to the topic of Fred’s dissertation, and much to everyone’s relief, Fred entertained the remaining guests as he shared his passion for his subject.

‘Did I conquer King’s by being so novel—so naive but potentially promising?’ he was later to wonder. He never attempted to deny his origins, developing a good-humoured critical awareness of English class snobbery, chuckling at the naivety of the elite classes as much as his own. He enjoyed telling how, at a dinner party given by Keynes, he was faced with a plate of oysters for the first time in his life. Fred was visibly embarrassed, not sure what to do with this disgusting looking delicacy especially when his host asked ‘Well, Clayton, which are you, a swallower or a chewer?’ The uproarious laughter of his fellow diners made him suspect there was more than a hint of innuendo in Keynes’ question. Ignoring this, he tried to focus on the task in hand, deciding to go for swallowing, as it would surely go down quicker, trying not to think of all those faces looking at him. Later on, he would be able to see the funny side of this incident, even if he didn’t at the time.

Though he eventually got used to the teasing, Fred was irked more by the way that his background made him a target for those who wanted to enlist him in their political cause. He experienced this one evening in November 1933 when he was having drinks with his new friend and fellow Kingsman, Alan Turing in the Junior Common Room of Trinity College. Fred had first got acquainted with Turing through rowing. Though he wasn’t sporty, his slight size did give him certain advantages and he became cox for Turing’s boat. They quickly became friends, discovering a mutual recognition and understanding of their intellect and their shared experience of being outsiders – Fred, because of his diminutive size and working-class background, and Alan, his sexuality. Fred was very interested in exchanging views and emotional experiences, and was drawn to Turing, who was always very frank and open with Fred about his homosexuality, sharing stories about his experiences at public school. Fred was in awe of Alan’s confidence in this area, as he himself felt more than confused – he’d been told by a Fellow he seemed ‘a pretty normal bisexual male’, but this was completely out of his experience. He didn’t know what he was and besides, even if he felt drawn to his own gender, he knew he would never be able to explore this; not only did it seem culturally impossible for a man of his background, but it was also illegal. To make matters worse, Fred had almost no access to or experience of any woman other than his mother. He felt he’d never had the opportunity to be attracted to women – any he’d come across seemed either formidable and frightening, or seemed to barely acknowledge his existence, probably because he was too small, a boy in their eyes.

Fred was an avid reader, devouring Havelock Ellis’s Psychology of Sex and Freud, and also made discoveries in the classics which he would convey to Turing who was a mathematician and knew little of Latin and Greek. Fred was in the middle of sharing his latest discovery with Turing in the Common Room bar when they were approached by a man with movie star good looks wearing a striped suit jacket, spotted tie, and cream trousers – ostentatious, even for Cambridge. He nodded to Alan, and focused his attention on Fred. ‘Hello, I don’t believe we’ve met. Can I get you a drink? I’m having a Gin Fizz – would you like the same?’

‘Oh, thank you – no, half a mild, thank you.’

‘Right you are.’ The man sauntered towards the bar.

‘You’ve caught someone’s eye,’ Alan muttered. ‘Believe me, I can tell.’

‘What do you mean?’ Fred protested. ‘Oh stop it, Alan.’

Turing raised his eyebrow, but before the conversation could continue, the man returned to the table. ‘Mind if I join you?’ and sat down without waiting for an answer. ‘So, you’re clearly not from around here.’

‘No, I’m from Liverpool.’

‘Liverpool? How interesting! I’ve heard things are terrible up there. Thousands of people unemployed. It just goes to show that the capitalist system is utterly bankrupt. I’m sick of it and so are a lot of us, I suppose that’s what took me into the Party. They’re a great bunch. There’s a demonstration happening at the weekend for the Armistice Day celebrations by the War Memorial. Why don’t you join us? I’ve heard you’ll be there, Turing, won’t you?’

Turing nodded.

‘Well, I, err, I’m not sure what my plans are yet,’ Fred replied.

‘Oh, right,’ the man responded, seemingly affronted, ‘Anyway, I must be going.’ He proffered his hand, ‘Nice to meet you – ’

‘Fred Clayton.’

‘I’m Burgess. Guy Burgess. I’m sure we’ll meet again.’

Fred felt perplexed by this encounter. At first, he was flattered by the interest shown in him, but he wasn’t sure what it was about him that had piqued Burgess’ interest. Over time, though, he came to realise that because of his modest origins, it was assumed that he would be naturally sympathetic to the burgeoning Communist movement, but it wasn’t quite that simple for Fred – things never were. He found it galling that upper-class public schoolboys, Old Etonians, like Burgess, were trading on their style and charm and sounding off about the working class, whilst knowing very little. They pressed Fred very hard in their attempts to convert him. But he distrusted their dogmatism, the extension of Marxism to all the spheres of life, and sometimes their remarks seemed plain daft. He couldn’t get over his suspicion that he was a target so that he could become the token working class member of the Communist party and he also didn’t like their tactics. He didn’t like being encircled.

Another day, Fred was sitting with Turing on the Bodley’s Court lawn (it was a favourite spot that year as Turing’s room was on the 3rd floor of Bodley’s building; they would often make their way over there after dinner). They were sitting on the impeccably cut lawn, enjoying the evening sunshine, looking out to the trees by the river, when they heard the familiar clipped voice. ‘Turing. Clayton. Together again. Thought I’d find you here.’ Without waiting for an invitation, Burgess sat down and continued, ‘You know, Clayton, of all the people here you really should join the British Communist Party – we understand the sufferings the oppressed working classes, I’m surprised at you, really, coming from where you do...’

Fred and Turing exchanged exasperated looks; Fred had lost count of the number of times Burgess, Blunt and their associates had attempted to recruit him. Until this point, he had joined in their discussions, good-humouredly batted their attempts away, but after Burgess ignored his polite refusals a second time, something snapped.

Fred stood up. ‘Look, Burgess. I know you’d like me to be your poster boy and you go on as though you really know what it’s like for us poor backward people in the depressed North. You pontificate about the working classes and lecture me on their sufferings, but you don’t have a bloody clue what you’re talking about. I doubt you even know anyone in the working class – and no, I don’t really count, do I? You think that Communism is the sole safeguard of peace on earth, but refuse to look at the atrocities that are being done to opponents of Stalin and his cronies in Russia – the only peace for those who don’t toe the line there is in the grave. Quite frankly, I’ve had it up to here. I won’t be joining you, now, or ever.’

Fred glanced over at Turing who could barely suppress the grin on his face. ‘I’ll see you later, Alan, I’m going back to my room.’ He swept off, leaving Burgess with a stupefied expression on his face, for once, speechless.

Despite this resistance Fred was a political animal. He was a convinced pacifist, but he wouldn’t pin his beliefs to one particular political mast; he refused to be boxed in. He distrusted the national stereotyping that was painting all Germans as villains, and he never lacked the courage to weigh into the political debate and air his own political opinions, however controversial. Thus, when he was appointed editor of the important Cambridge Review – the youngest ever, at only 20, as well as the first to come from a non-Public School, he was determined to shake up what he saw as a rather grey, dull, publication. He excelled at the job, but it made him sick with worry. He never re-read what he wrote, hoped it was good, and was always rushing on to next week, all the while trying to write his fellowship dissertation, which, after all, was what he’d got the grant for.

As well as the staple of reviews of theatrical performances and new books, Fred saw his tenure as editor of the Cambridge Review as an opportunity to raise awareness of the political debates that he found himself embroiled in, publishing articles first criticising then defending Marxism. Then, inspired by his own experience, in February 1935 he penned a satirical article entitled, ‘Conversations with Communists’. This alluded to the way that Communists would manage to relate every topic and conversation to the class struggle. The article envisages a new parlour game:

The object of the game might be described as not so much to keep the ball rolling, as is done in orthodox conversation, as to roll it on to the class-struggle. It is assumed by your opponent, for the purposes of the game, that a point is scored whenever the class-struggle emerges naked and unashamed on to the carpet. I say ‘for the purposes of the game,’ because it is doubtful whether any further end is served.

The article then continues to give advice about how one might play the game successfully and concludes:

How cynical you are allowed to be is a difficult question. I think it should be considered a foul to say ‘Blast the masses!’ On the other hand, some players consider that all's fair in this game. My own opinion’s that, if used at all, this species of body-line should be reserved for when your opponent threatens to produce ‘the facts’. But, even then, may I say, here and now, that I consider it in the worst of taste?

Fred knew he was stirring a hornet’s nest and he continued to do so a fortnight later by publishing letters on the subject as well as an article that defended Communism and criticised him:

Only a self-conscious and intelligent writer like F. C. must realise just how much he is rejecting. He is saying, in effect: the suffering and oppression of the majority of men does not interest me; I refuse to allow it to interest me; I shall laugh at the idea that it interests anybody; and it certainly has no relevance whatever to anything that I may think or do.

In the same issue of the Cambridge Review, he published an article about the forthcoming visit to Cambridge of Sir Oswald Mosley who would be attending a dinner of the University Branch of the British Union of Fascists. Warning of the dangers posed by Fascism in Britain, contributor Colin Clout argued,

It is hardly necessary to point out the disaster that would overtake English culture if Fascism should gain the ascendency in England. The Fascist state has no use for advanced culture. It cannot utilise the inventions of scientific workers. It does not want highly trained critical brains, but dull-witted brawns that will serve its interests and fight its wars without criticism or question.

As yet Fascism in England is only a small cloud on the horizon, no bigger than a man's hand. But in times of storm and crisis such a cloud may swell until it darkens the air. Let this be a warning to all those who have the interests of culture at heart, who are concerned for the future of Cambridge and all it stands for.

These articles in the Cambridge Review were provocative both to Communist and Fascist students and staff and also those dons who didn’t seem aware of the strong wave of somewhat startling, very radical opinion that was sweeping the university. At first it was fun, as he enjoyed imagining the raised eyebrows in Senior Common Rooms across the city; however, it became less so as he realised he had pushed it too far, ending his tenure as editor having offended both sides of the argument and a threatened libel on his hands.