Award Category

Screenplay Award Category

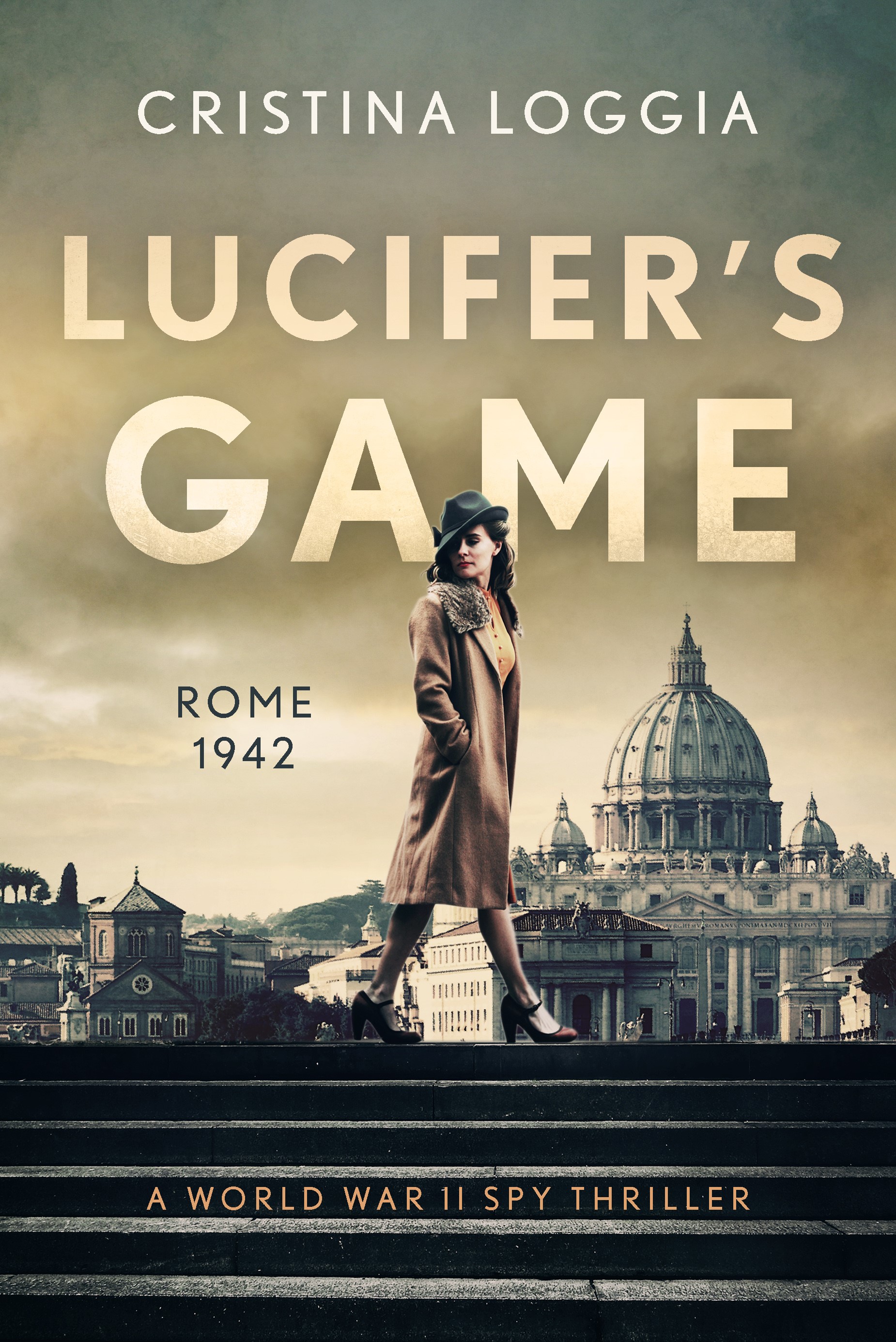

Cordelia Olivieri, in an effort to protect her Jewish heritage and secure safe passage out of Mussolini's Fascist Italy, forms a dangerous alliance with the British secret service, who wants her to steal crucial intelligence that will push the Axis out of North Africa once and for all.

This submission is private and only visible to judges.