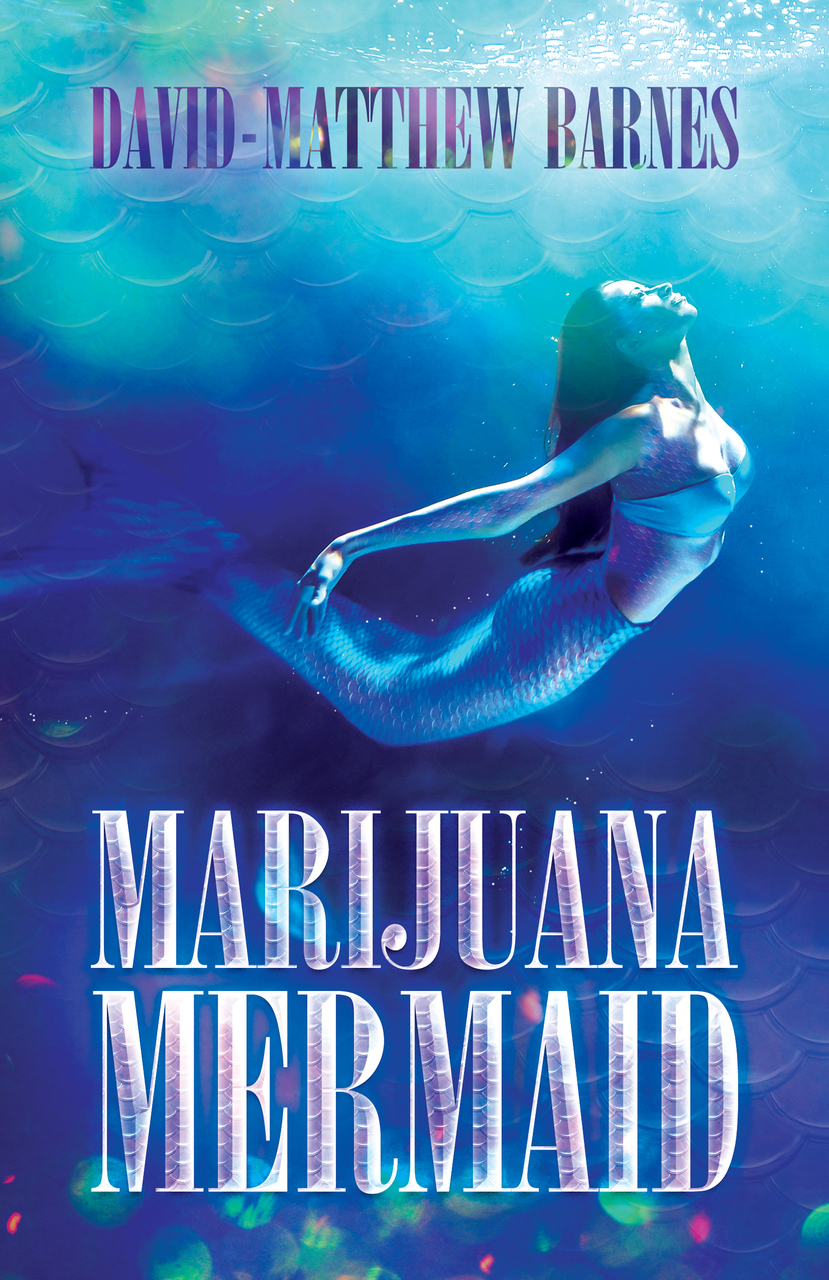

Marijuana Mermaid

The Aquarium

My mother barely spoke to me during our stop-and-go drive to O’Hare. Traffic was bad. She muttered a few profanities under her breath, frustrated. I realized her anger was directed at the other drivers, but I also knew she was still pissed at me. Rightfully so. I remained a silent passenger, convinced if I opened my mouth, I’d say the usual wrong thing and add to the damage I’d caused.

It wasn’t until she pulled up to the curb under a sign that said Departures that my mother said, “I really hope you don’t screw this up, Leah.” To dig the knife in deeper, she added, “Your father didn’t have to agree to this, you know.”

I reached for the door handle, anxious to escape. “I know.”

Realizing this was the last face-to-face conversation I’d have with my mother for the foreseen future, I wrestled with the heavy need to say something more, but the words wouldn’t come. What could I possibly say to her after what I’d done? I’m sorry you have such a screw up for a daughter. Forgive me for the fire and the Vodka. I don’t want to leave you. Chicago is where I belong. I promise not to be so awful to you. Please let me stay.

Once out of the car, she fished my suitcase from the trunk. I grabbed the handle of it and squeezed. Then, we stopped moving. My mother looked into my eyes. I tried my best to avoid her stare or the fact that she looked much older than she was in my mind when I replayed conversations between us, real and otherwise. “You need to make California work for you.”

I nodded. “I will.”

She leaned in and we shared a very awkward, very obligatory hug. “Have a safe flight.” She turned back to the car. I watched her slide in behind the steering wheel and check her mirrors before inching out into the stream of airport traffic. Then, she was gone.

I wasn’t certain, but I could have sworn there were tears in her eyes.

Later, after checking in my suitcase, printing up my boarding pass, and making it through security, I jumped in line at a coffee shop near my gate. I ordered a large iced caramel chai latte, knowing I would regret doing so later on the plane when I would definitely have to pee.

Like an orphan, I walked alone to the gate, sipping on my drink. People moved around me, rushing to another scene in their lives. I found a seat in the waiting area that faced the glass. Through the window, I could see the plane being prepped by the ground crew. It was just a matter of minutes before boarding would begin. I plugged my phone charger into an available outlet but then felt dumb for doing so. Who was I going to call? Who was going to text me? My mother? She was probably already back home, standing in the center of our apartment, relishing her newfound freedom. My father? Not likely. I suspected he was too busy stressing about my arrival and the years neither of us had made a solid effort to be a part of each other’s lives. My friends? I could count them on one hand.

Then, I drifted back to a memory I’d long forgotten. I was young, around nine. My mother had decided we were going to spend the day together, just the two of us. We started off the morning with a big breakfast at a restaurant on State Street. Then a walk through Millennium Park. We finally made our way to the Shedd Aquarium, which instantly became my favorite place I’d ever been.

We were standing in the Wild Reef section. I was in awe and staring through the glass at the underwater world in front of me, wanting to join the fish and their aquatic world.

“I need to tell you something,” is how my mother began the conversation. To my surprise, she reached for my hand and held it. “Your father and I…” It was a rare moment. My mother was at a loss for words. Never before had she seemed so affected by something. An immediate sense of dread hit me. I let go of her hand.

“Your father and I are getting a divorce, Leah.”

I don’t remember what my mother said after that. I pressed my forehead against the cool glass and begged for the fish to bring me home. They were my new family. My old one was broken.

After the gate agent made the boarding announcement, I unplugged my charger and shoved it into my front pocket. Now in line with the other weary passengers, I clung to my boarding pass like my life depended on it. Outside, the sun was setting. The sky was a mixture of sherbet orange and pale pink.

Already, I missed Chicago – the girl I used to be. I knew she was still somewhere in the aquarium, hoping someone would find her, take her home, and teach her to swim.

The Mermaids

“It’s dark, so it will be difficult to see,” my father said, “but I’m taking you to the ocean.”

His words floated between us in the car. They blended perfectly with the green glow from the dashboard lights and the occasional splash of passing neon signs. Both created the ambiance of a movie-moment. As my father drove us down a winding highway, it felt like someone tucked me inside of a kaleidoscope, with patterns, reflections, and shadows tiptoeing across my skin. The road teetered next to the edges of cliffs I couldn’t see from the passenger window but saw pictures of during an online search of the place two days ago, while still in Chicago.

Someone should film this, I thought. Our first form of father-daughter bonding. At least, that’s what I think this is.

He continued his thought. “I know you’ll love the water as much as I do. That’s why I moved here…really. There’s no other place like Seaside Heights.”

His words made me smile. For a moment, I wondered if I imagined them. I was exhausted. No. It was worse than that. I was on the edge of insanity. I had been for the last six months. But the flight had done me in. It didn’t help that despite a bright moon, I couldn’t make out much from my view in the moving car. Yet, a part of me didn’t even care. I had no choice. Whether I liked Seaside Heights or not, it would be home now. Until I turned eighteen. Then, I had no idea where I would end up. At least for now it wouldn’t be a juvenile detention center in Illinois. I needed California to give me a second chance. Otherwise, I was doomed.

“Now?” I asked. “We’re going to the beach right now? Isn’t it late?”

My father nodded. His smile and excitement illuminated the space between us. I loved his expression—a boyish grin mixed with what was left of his legendary, rebellious youth. It made me love him even more. It gave me hope that my new life might not be so bad.

Unlike the radical skateboard-riding poet he used to be, my father owned a used book store now and looked the part, down to the black- rimmed hipster glasses and thinning hair. We were so different, complete opposites. I was the only brunette in our family, the unofficially elected Black Sheep. I’d been doing my best to live up to that silent expectation, unintentionally, of course.

I looked at him again, trying to imagine what he was like at seventeen. If I wasn’t his daughter and he was just some cool guy I knew from school, would I talk to him? Would we be friends? See each other at the same parties? Have classes together?

I bet you were so fun when you were young. How in the hell did you ever end up with such a hypercritical bitch like my boring mother? No wonder you left her.

“I promised you,” my father said, reminding me about a phone conversation we’d had less than forty-eight hours ago when my fate had been decided for me. “Seeing the ocean was the first thing we would do when you got here.”

“You remembered,” I said, still searching for anything revealed by the moon. A palm tree. A sleeping seagull. A late-night surfer. Nothing.

“Of course, I did.” He almost sounded hurt.

I tried to muster up as much excitement as possible and said, “I’ve really been looking forward to this.”

His grin was back. I could hear it in his voice. “I might even walk down to the water with you.”

His energy, now amped up, was contagious. I couldn’t help but smile, despite my tired state. “Are you always this adventurous?”

He shrugged and continued to beam.

For a second, I imagined us with the windows rolled down, wind in our faces, sharing a bottle of century-old tequila, laughing at some cheesy song on the radio, exhilarated by the fact we were both bad asses born to break every rule.

“I don’t remember you being this daring,” I said. “What happened to the well-behaved father I saw two years ago?”

“Strange,” he said. “I’ve been thinking the same thing about you since we left the airport.” The mood shifted. The magic I was sensing disappeared. Some evil force snuck inside of the car and killed it.

That sounds like something mom would say. Did she put you up to this?

“Airports are overrated,” I said. We pulled into a space in an empty parking lot facing the horizon. I stared in awe. Sand and waves. The moon on the water. It took my breath away. “But this isn’t.… Holy shit…Dad…this is incredible,” I said. “This is where I live now?”

My father turned off the car. The sudden hush made me anxious. Silence freaked me out. It always had.

He slid the key out of the ignition and closed his hand around it. “You messed up,” he said.

I kept my eyes on the shore. I nodded and said, “I know.”

More silence. The seat belt suddenly felt tight against my body.

“Your mother doesn’t know what to do with you,” he said.

“And you do?” I asked. “We haven’t lived together since I was nine. Why now?”

“You almost went to jail.” As if I needed one more person to remind me of my not-so-distant past. “You’re all out of options, Leah.”

A life guard stand in the near distance, tall and white, snagged my attention. It looked like a wooden soldier. I wondered if I had the energy left to climb it, to get a great view of the water. I locked my eyes on it, staring at it through the windshield. I imagined some hot guy up there, waiting for me in red board shorts and a white tank. Maybe he was the answer to all my problems. Or maybe he could just teach me how to become a better swimmer.

I turned away from the imaginary lifeguard and my father. I stared out my window at a blue and rusted metal garbage can covered in what I assumed was seagull shit.

“You’re my last resort?”

My father cleared his throat before he spoke. “You’re going to be eighteen in less than a year.”

“Then you’re setting me free?” I asked, wondering if he was counting down the days.

He let out a deep breath as if he’d been holding it in since we left the airport. “I want you to use this year to get your shit together.”

“At the beach?” I couldn’t help myself. I was known for picking the wrong moments to be a complete smart- ass. It was just a talent I’d been born with. One that irritated everyone I knew.

“You’ve got one more shot,” my father said. His words sounded firm. “That’s all I can give you.”

I shifted in my seat, hoping the seat belt would show me some sympathy. “Dad, I know you didn’t plan on having me come live with you.”

He shrugged, tense. His body was rigid like a filing cabinet. Already I missed the moment between us that just passed. “It was the only way the school board would agree not to press charges.”

Frustrated, I freed myself from the seat belt and reached for the door handle. “I’ll try to stay out of the way.”

My father touched my arm. Gently, he was trying to stop me from moving. From jumping. “You’re not in the way,” he said. “I just know…you’re better than this.”

It was the first time in over a month anyone had shown a sliver of faith in me. I thought of my former English teacher back in Chicago and how much I had disappointed her. “You’re such a smart girl,” she said to me in September, when she decided I was destined to become the future winner of a Pulitzer Prize.

Clearly, she was wrong. Smart girls don’t get sent off on a late-night flight to the west coast like some illegal drug being smuggled across borders.

“You should think about becoming a writer,” Miss Rebecca Olivares said right before I did the stupidest thing I’d ever done in my life. “You have a lot to say…you seem to have a real handle on poetry.” I’m pretty sure the only reason why she said this is because I was the only student in eleventh-grade English who actually knew who Emily Dickinson was – not because I was some poetic prodigy. Besides, my father was the real poet in our family. Or at least he used to be.

“Just because I know a lot of big words doesn’t make me a writer,” I said to her.

“No,” she said, “but your love of language does.”

Miss Olivares was right about that. I was once addicted to reading anything I could get my hands on. When I stopped reading, I got into the worst trouble I’d ever been in.

As my punishment, I now stood barefoot in the sand, shoulder to shoulder with my father, staring out at the surface of the Pacific, complete with the reflection of the brilliant January moon.

“It was worth it,” I said to my father. “Getting into trouble. I’d do it all over again.”

“Why, Leah?” he asked. He sounded exasperated. His words were heavy and hopeless. Already I was disappointing him. Without even trying.

“So I could be here,” I said. “With you.”