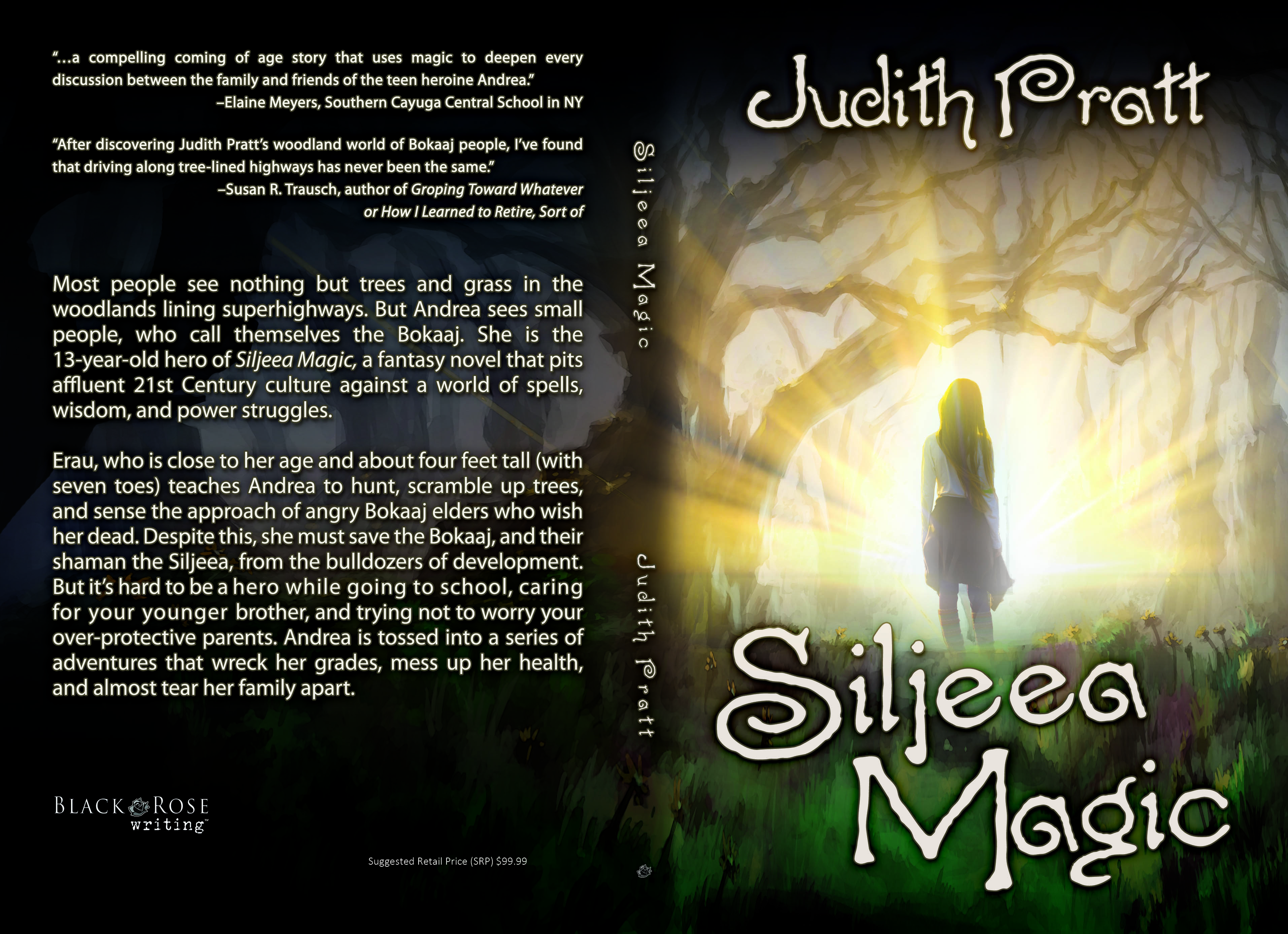

Siljeea Magic

Andrea, 13, finds small people in the woods, making friends with Erau, a Bokaaj boy. Then new road full of houses begins to chew up the woods. Andrea must keep the Bokaaj safe, while managing a new school, overprotective parents, and a bratty younger brother

Chapter 1

We were driving along a four-lane highway when I first saw them. Small brown people, standing in the woods that bordered the road.

I had just turned seven and had been imagining myself on a beautiful palomino horse, whose smooth gallop kept magical pace with our car. I used to do weird things like that when I was a kid. Suddenly, instead of the fantasy horse, I saw real people standing among the bare trees. They were child-sized, but I knew they weren’t children. They were the color of the dried oak leaves and pine needles under their feet, so they should have been almost invisible. But I could see them.

At first, they felt like part of my daydreams, like I’d flicked from one fantasy to another. When I was young, I was always fantasizing about something—wizards, flying horses, dragons. Having adventures. Becoming a hero.

But the next time I saw the people, our car was now going the other way on the same giant road. I couldn’t help saying, “Look!”

“What, dear?” said my mother from the back seat, where she sat to make sure my baby brother Jake didn’t get bored in his backward-facing car seat and begin to scream.

“Small people,” I said, pointing. “They must live in those woods!”

“Yes dear,” Mom said. My stepfather Craig frowned at me—I sat next to him in the front seat—but he frowns a lot. Mom says he works too hard.

Jake said something that sounded like “Hah ba ba ba ba,” and my mom said, “Yes! Bear-Bear!” He certainly did love his fuzzy bear toy; it was always covered in drool. Jake must have been about eight months old that summer, not talking, only babbling. Too bad that didn’t last.

“Where do those woods go?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” Mom said. “Usually there are houses or industrial parks behind them.”

“Why are they there? I mean, why don’t people live there? It’s a waste of space.” My stepfather sometimes called people a “waste of space,” and I liked the phrase.

“They’re buffer zones,” Craig said. “They keep the highway away from the houses, so children who live in the houses won’t run onto the highway.”

“I wouldn’t run onto the highway,” I said virtuously.

Then Craig’s phone went off, and he talked into his headset, while Mom played with Jake and I stared out the window at the buffer zone waste places, looking for more of the small brown people.

Every weekend, as we drove on the giant roads to visit my grandmother in her condo, or go to parties with friends of my parents, I looked for the small people, the Buffer Zone people. It needed a lot of concentration, and some kind of inner shift, like seeing a pattern in a random collection of dots, like the ones in the comic pages of the newspaper. My birth father loved the comics printed in the Sunday newspapers. He used to read them to me when I was too young to be able to read them myself. Before the divorce. I still read the Sunday comics. My parents read the opinion pages and worry about the state of the world. I have more fun than they do.

At first, in those random dot things, the picture just looks like scribbles. But if you hold the page at your nose, and slowly move it away, it comes into focus as a 3D boat, or a word, or something. Seeing the small people was kind of like that.

Trying to see them made my head feel fat like I’d been too long on one of those merry-go-round things they have on playgrounds. Looking back, I wonder if I hadn’t spent my first four years in a city apartment, and the last three in a big old house in Newton with a tiny yard surrounded by fences, would I have seen the small people? Maybe I would have thought they were deer, or squirrels, or even foxes. But the biggest animal I’d ever seen, outside of a zoo, was a squirrel. For whatever reason, I knew perfectly well that I was seeing people, not deer or foxes. Or squirrels.

Then one day, when we were stuck in a line of traffic getting off the highway, I spotted four Buffer Zone people very clearly. They were sitting in the bushes that grew under the trees.

“There they are again, “I announced. “Those small people that live in the woods. In the buffer zones. What do they eat? Do they have houses? How do they live when it gets cold?”

My stepfather turned his head to frown at me. “Andrea,” he said, “those are just fantasy people. Like in all those books you read.”

“No, they aren’t,” I said, frustrated. “These people are real!” We turned off onto one of those ramp things, going even more slowly. “Right there!” I pointed. The Buffer Zone people were gathering something from the ground. “Don’t you see them?”

My stepfather sighed and shook his head; then glanced at my mom in the rear-view mirror.

That glance told me that something was wrong, but I didn’t find out what until a few days later when Mom came into my room one evening. After she had married Craig Kimball, we’d moved to a house in Newton, where I had my own bedroom. It was tiny, with spectacularly ugly turquoise wallpaper with pink poodles on it, but it was mine. In the apartment that Mom and I had together before Craig and after the divorce, we had to share a bedroom.

“How are things, Bug?” asked Mom. When I was a baby, Mom and my birth father, Mike, called me Bug because, Mom said, “I crawled constantly, exploring every corner of the apartment.”

“Good,” I said, looking up from my book.

“What are you reading now?”

I showed her. It was one of the Narnia books.

“Is it a story about woodland people?” Both Mom and my stepfather are totally clueless about the books I like to read. Mom writes marketing materials, and Craig had started his own computer development company. They read what my stepfather calls “non-fiction.” He says it as if “fiction” is kind of silly.

“No,” I said. “I haven’t found any books about them yet.”

“So you made them up all by yourself,” Mom said, admiringly.

“No,” I said.

“Honey, you know they aren’t real, don’t you?”

I did not know that. I’d seen them. I’d learned how to see them. But Mom had that little wrinkle between her eyes that she’d had so often before she married Craig Kimball.

Now, I think about all the time I wasted, when I could have maybe found a way to meet the small people. But before Mom married again, it was just the two of us, and she had that little wrinkle all the time.

My birth father, Mike Jernigan, left before I turned three. After that, he’d visit and take me to the park. I loved the worn grass and spindly trees. I was a city kid and didn’t know any better; didn’t know anything about forests full of huge trees. Mom was working, so I was always in daycare and nursery school and after-school programs. They didn’t have grass or trees. They playgrounds all had that spongy stuff underneath instead of grass.

Even when I was only four years old, I knew that Mom worked too hard and that she was unhappy. Then Craig came along, and we moved to Newton, and that little line faded out of Mom’s face. I didn’t want to bring it back.

So, when Mom said the woodland people weren’t real, I said: “I guess so.” She smiled and left me with my book, and I never mentioned the buffer zone people again. I still saw them. Sometimes they were sitting under the trees, watching the cars whiz by. Now and then I’d see them in those little hollows that the off-and-on ramps circle around.

I started to look at maps, so I’d know where we were when I saw them. I kept a secret locked journal using a code: “7/4/14 Rte 3 Taunton 3 sitting.” Which meant I saw three buffer zone people on our way to Taunton for a party with my parent’s friends. Or “11/22/14 Nana 4 running,” meaning that I saw four buffer zone people running through the woods along the highway when we were on our way to Nana’s condo for Thanksgiving. I still have the journal. It’s still secret, and it’s still locked.

Chapter 2

One day in early June, when I was sitting in our back yard, in my special place under the pine tree, reading and wondering what I’d get for my 12th birthday, my parents both came home from work early.

“Put down your book,” Mom called to me, as she got out of the car. “We have wonderful news.”

I was at the most exciting place in the book, so she had to call me a couple of times, until Susanna, who took care of Jake and me after school, came out to say goodbye. “Your mama wants you,” she added, sternly. I hadn’t finished the exciting part yet, but I draggled into the kitchen, where Mom and Craig were sitting at the table looking at a bunch of drawings.

“We’re moving to a brand-new house!” Mom told me, eyes sparkling. “With a bigger yard, and a playroom, and a wonderful new school!”

I hated the idea. I’d gone to the same school all my life. In the second grade, I made friends with Kathy O’Keefe because she was the second-best reader. I was the first best reader. Kathy has red curly hair and zillions of freckles. I never had freckles, and when I first met her, I thought her freckles were amazing. I wanted some. But I have sallow skin that tans a little bit, with never a freckle.

When Kathy and I started third grade, a new girl, Sally Bacon, came to our school. Before anyone could laugh at her last name, she said, “Most people call me Crispy!” She has light brown skin and gorgeous black curls because her father is African American. Kathy and I became friends with her and made up nicknames for ourselves. Kathy was “Teeth,” short for “O’Keefe,” and I was “Germ,” because my last name is Jernigan. We thought those names were hilarious and kept it up even after we knew how childish it was.

If we moved, I’d have to leave Kathy and Sally. We walked to school together every day. We ate lunch together. I liked visiting them. Kathy’s mother seemed hardly a mother at all. She didn’t care if we made a huge mess doing our projects. She even let us use her iron to put fall leaves between waxed paper. My stepfather would have freaked if he knew I was using a hot, dangerous iron when I was only ten.

“Our house is fine,” I said. “It’s perfect. Besides, I can’t leave Kathy and Sally. They’re my best friends.”

“You can write to them,” Mom said. Before I could announce that she did not understand anything, she said, “Look, these are the house plans.” She pointed somewhere on the drawing. “See, this is your room. It’s huge. And you can pick out the color of the walls!” Since I hated the turquoise wallpaper in my bedroom, that should have made me happy. It didn’t. My mother didn’t care about my friends. She was ruining my life.

“How about black?” I said. Then I stomped upstairs and sulked in my ugly turquoise bedroom.

A couple of months later, on a Saturday, we all went out to see the new house. The drive took more than an hour. We drove along a big highway to another big highway to Tillens Farm Road, wound around a couple of curves, and turned onto Whippoorwill Lane. I thought Whippoorwill was a dumb name. Much later, I heard an actual whippoorwill bird and realized that’s just how they sound: “chirp-ooo-WILL.”

The house was immense. Our Newton house could fit into this place three times, I thought, grumpily. Everything echoed, the walls hadn’t been painted, the floors were plain plywood, and the yard was all dirt.

“It’s a mess,” I said.

Craig grinned at me. Craig never got excited about anything, but he was excited about this. “It’s not finished yet,” he said. “It should be ready by August, just in time for you to go to your new school.”

I did not want to go to a new school. “It smells funny,” I complained.

“Fresh plaster,” Craig said. “Sawdust.”

“Come upstairs and see your room,” Mom called.

Jake, now an obnoxious five-year-old, liked the echoes and started to run around screeching. “Stop that this minute, young man,” Craig yelled. Glad to get away from the resulting argument, I thumped up the stairs, making even more echoes.

The walls hadn’t been finished. They were all open frames, so I could see through them to the rest of the upstairs. But I could tell that my new room was twice as big as my Newton bedroom. My furniture would be lost in it. So would I. “Look at the size of this closet,” Mom said, walking through a wall to show me how big it was going to be. I ignored her. I had never been interested in clothes. The last thing I needed was a giant closet.

Mom tried again. “What color would you like on the walls?”

I hated everything. I did not want to move. I did not want to leave my friends. “I don’t care,” I said, turning my back on the open walls and the not-quite-closet to look out the window.

Behind the house, a stretch of dirt stopped at a chain link fence. Behind that fence lay a forest. A huge tree hung its branches over the fence to shade the yard.

“What’s behind those woods?” I asked.

“What?” said Mom. “Oh, probably the highway we came in on. It’s very convenient for your Dad’s commute.”

Buffer Zone people lived along the big highways. Buffer Zone people could be living right behind our new house. If I lived here, I could find a way to meet them.

“They’re pretty, those woods,” I said, suddenly all cheerful. “Could we paint my bedroom yellow?”

Now, when we visited our new house so my parents could decide about colors and bathroom tiles, I got as enthusiastic as they did. They were thinking about the house; I was thinking about the small reddish brown buffer zone people.

We were supposed to move in late August, in time for the new school year, but for some reason, the house wasn’t ready, so we couldn’t move in until March, just after my Newton school let out for spring break. My stepfather spent all those months yelling at people on the phone, asking them if they could plan their way out of a paper bag, and saying words that Jake copied until Mom explained, while glaring at Craig, that only grown-ups used those words.

When we finally moved in, the pale yellow walls in my new bedroom looked great with my old black-and-white striped comforter. Mom let me keep my bed, but insisted on buying a new desk, which I loved, and a new chest of drawers, which she was excited about and I wasn’t. My clothes took up just two of the four drawers, but the top was a good place for some of my books. After I had made several disorganized piles of books on the bureau and the floor, Mom bought me an actual bookcase.

The first night in the new house, I woke up at 5:17 and couldn’t go back to sleep. I’d slept in the same room in the same house for six years. This place felt too strange. In Newton, you could hear cars going by, and, in summer, people chatting out on their porches. In this new house, the silence hissed at me. After trying to read myself to sleep and failing, I went to the bathroom for water. While sipping, I looked out the window into the woods. It had just started to get light, although the trees and bushes made the forest all shadowy.

One of the Buffer Zone people was standing in the woods, right at our fence.

At first, I told myself it was some neighbor, then I told myself it was a homeless person. But I knew it was a Buffer Zone person, even though I’d never seen one so still, so close up. Small, smaller than a human. Wearing old, slightly ragged clothes. Bare feet, one of them curled onto the fence, like he—okay, it could have been a she, I had no idea—like he or she was thinking about climbing it. The person seemed to be staring right at me. I could see the gleam of eyes. And I shivered. This Buffer Zone person hated us. Probably wanted to kill us.

I discovered that I’d crouched down below the windowsill, hiding from that fierce stare, tucking my head between my shoulders. This is stupid, I thought, as I curled up on the bathroom floor, how can I be scared of someone so small, who’s safely behind a fence. Because he might climb it, my thought answered itself. In sudden terror, I stood up. But when I looked out the window again, the person was gone. And I felt shaky all over. My Buffer Zone people hated me, hated our house, and were evil and terrifying. I ran back to bed, turned on a light, and pulled the covers over my head.

The next morning, I convinced myself it had definitely been a dream. Only in dreams do you think someone is evil when you can hardly see them.

Comments

Cute start!!

I loved this. :)