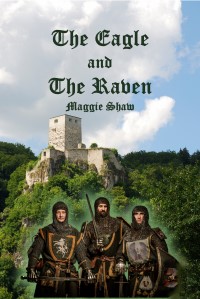

The Eagle and The Raven

Chapter 1

The Messenger

A fist pounded urgently on the tavern door. We travellers looked up from our bread and stew to watch the ostler check the bolts on the door were fast. It was evening, and this remote roadside inn at the base of the long moorland ridge of Rabenwald was not the place to welcome strangers after curfew.

‘Who is it?’ the ostler demanded.

‘It’s Thiemo. Help me, please!’

‘Let him in, Herman,’ said the widowed innkeeper, Frau Engel. She was a plump, homely woman dressed in a practical beige linen tunic. She looked more than capable of taking care of herself in her sometimes tough line of work.

Her son, the lean ostler, drew back the bolts and cautiously opened the door. He checked to make sure the caller was who he claimed and pulled the thin young man inside. Thiemo dragged himself to the bar. His ragged clothes were muddy and he looked bruised and bloodied from a fight.

‘What’s happened to you, Thiemo?’ Frau Engel asked.

She put a motherly arm around his shoulders and offered him some food. He shook her off.

‘Not now, Frau Engel. Is there a messenger here?’ he demanded.

The five travellers shook their heads, not wanting to get involved. I saw the pain on the young man’s sallow, bearded face and sensed he sought to send a message rather than learn one.

‘I am Guide Gendal. An it be important, I will take a message for you, lad.’

‘Heavens be praised – at last a rider willing. For my master’s sake, leave your meal, and ride to the Iyver tavern on Rabenmoss. There seek out Count Bertram.’

‘Hold, young sir. Oft have I ridden Rabenwald, but never has the Iyver welcomed me. It is a local spot.’

‘Aye, but the name of Count Bertram and the message will gain you entry. For Raban is dead.’

A knife clattered. Frau Engel blushed.

‘Heaven save them and him,’ she whispered.

‘How did it happen, Thiemo?’ the ostler demanded, his mouth agape in dismay.

‘Not now! Precious time is being wasted!’

‘Aye, but my horse could use a little rest after our hard day,’ I said, my mouth full. Whatever his urgency, I needed more than a mouthful of sopped bread to face Rabenwald’s night. ‘If I am to ride with such heavy news, I should know more. Count Bertram is sure to question me.’

Thiemo nodded and sat at our table. My tall, blond companion Rehlein Hirschmann moved his plate to give him room. The ostler gave the young man a tankard of ale.

Thiemo eyed my black brigandine with some interest. He recognised the studded velvet jacket lined with overlapping metal plates, as the coat of someone who was used to handling trouble on the road. He noticed too the seals on my rings: the splayed eagle of a free imperial knight, and my own splayed eagle overlaid with a butterfly. They seemed to give him confidence in me as he embarked on his tale.

‘Last week, Duke Nicolaus’ men arrested Raban and took him to Aunsberg. They tortured him to learn about the rebels. He said nothing and would have died by their hands. A soldier who was a secret sympathiser helped him escape. As they came south across Danuvia for Rabenwald, the Duke’s men overtook them. They killed the traitor and mortally wounded Raban. He fell at my door and died in my arms. With his last breath, he charged me to send word to Count Bertram, and gave me his ring. I ran to find a messenger. Thank you, stranger, for stepping forward.’

‘Yes, and stepping right back again,’ said Rehlein. My well-dressed friend was broad-shouldered with flabby muscles. Life had been kind to him, but that had been some time before he had joined me on the road. He warned, ‘Cara Gendal, I have no mind to go gallivanting on fell tops at the witching hour after a day’s ride.’

‘What, do you fear I will take your soul?’ I scoffed. ‘Forsake not your soft warm bed, friend – a messenger carrying this message is better off alone. Meet me at the Rabenwald Iyver tomorrow sunset, should Count Bertram let us stay there the night.’

‘He will, I promise you,’ said Thiemo: ‘All Rabenwald will respect you for your service.’

‘Are you also one of them, then?’

Thiemo leapt back, ale spilling, fearing me to be Duke Nicolaus’s spy.

‘Calm yourself, friend Thiemo,’ I said: ‘I am neutral in this region’s politics. As a true messenger, I will say naught about the sender elsewhere. My reason for asking is this. Though I know I do not support the cause, should the Duke’s men arrest me, they might not believe me. If your mission is innocent, forget my question and forgive me. If it is not, tell me, lest I forfeit my life and the message doesn’t get through.’

Thiemo nodded, settling again. He took Raban’s ring out of his pocket and looked fondly at it before handing it to me. It bore the Raven seal of the Count of Rabenwald.

‘Raban was my greatest teacher and my truest friend, though I was but one of many to him. Our pennons will skim the ground for him.’

He paused, but then broke down and wept, not selfishly but like a lover separated forever. His tears moved me.

‘Ostler, saddle my horse. I ride.’

Herman hurried to obey. I checked details of Rabenwald’s dangers with one of the other travellers, who had come off the hill that day. The man was short and portly with a greasy red face and dark beard. He wore expensive clothes for the class of inn where he had chosen to stay.

‘Be warned,’ he said in an accent that was not local: ‘It is a foolhardy mission. No self-respecting messenger would take it.’

‘Aye?’ said I: ‘Well, I have little respect, good sir, but I do have pride.’

I donned my cloak and strode out into the night-darkened stable yard. Rehlein followed and embraced me.

‘Welcome back, friend,’ he said as I opened the saddlebags on my black horse, Finstar. Rehlein recognised the ethical mountain I had crossed when I had weighed the political dangers and still said I would go.

I packed my brigandine and put on my padded leather gambeson coat instead. Though it would afford less protection in a straight fight, it was much quieter than the rattling plates of the brigandine. To ride out again after the curfew hour required more stealth than strength.

‘Nay: there is no change,’ I said: ‘This is still Eregendal, adventuring.’

‘Not to ride out tonight. Till tomorrow, at the Iyver.’

We clasped hands. I threw the reins over the pommel of the saddle, checked my longswords in their saddle scabbards, and mounted my horse.

‘Do you want a lantern?’ asked the ostler.

‘Nay: the rising moon is still near full. But you should take care. The travellers who rode off the hill today may well be the Duke’s men. One tried to warn me off.’

‘Thank you, friend, but they can do little here. This is Eiswald, not Danuvia.’

‘Perhaps. But what are ducal marches when Nicolaus is cousin to the King of Rome?’

I saluted and rode off into the night.

Chapter 2

The Message is Delivered

Rabenberg is an awkward mountain to travel even during the day. It grows out of the Eiswald plain as a wooded foothill spur of the Bavarian alps. I was glad of the moon’s early light to guide me through my memories of its paths. I rode its base westerly for three miles to pass the long side of treacherous ghylls, and at length climbed the safest ascent from the Eiswald plain, a worn sandstone-tipped granite spur stretching out from the forest into the fields. Its aggressive square-edged boulder cliffs slowed my ascent. Several times I had to lead my horse, hoping I would not lose the little-worn path in the moon’s cold light. At length I reached the brow of the spur and remounted to ride to the top of the fell’s last rounded bluff. When I rounded the bluff, I could see far: east across Eiswald to the distant Beyerischer forest, north towards Aunsberg, and south across the wetlands of Rabenmoss. I should have seen the lights of the Iyver to the south, but the bog was in darkness. I assumed the inn keeper slept.

The Iyver stood in the heart of Rabenmoss, on a small central island in a peat bog held in the bowl of mountain rock. Three main routes crossed the bog to the island, marked by whitewashed boulders. The easiest route of the three started from a sandstone outcrop which marked the entrance to the morass.

I doubled back along the lip of the mountain bowl for about four miles east to the sandstone outcrop. When I got there, I looked for the first white guide stone showing the way into the bog. It had vanished.

I did not know whether to set foot across the morass. What was more important: my safety, or the urgent nature of the message I carried?

Small lights gleamed in the near distance against the darkness to the north. As only Danuvia lay north, the lights could only be the lanterns of Duke Nicolaus’s men. It was after curfew time. If they found me abroad, they would give me no quarter.

I dismounted and led my horse into the bog, glad that I had refused the ostler’s lantern. Though the moon was setting, making it much harder fo see my way in the darkness, I could easily conceal my cloaked body and my black horse among the clumps of sedge.

Rabenmoss shuddered with an odour of earthy decay each time I placed a foot off the path onto the quaking peat. I recalled past ordeals crossing bogs and marshes, and used a technique I had learned from them, tapping the tarry surface with the toe of my riding boot until I found firmer ground. After a few steps, I stumbled over a reed clump and landed with my arms around a white boulder. What joy it was to find the guide stones had not gone, but were just hidden! I led my horse on across the bog in greater confidence.

Lights gathered by the sandstone outcrop marker at the edge of the mire. They were now only about three hundred paces away. The still night air carried the sounds of men’s voices speaking in an Italian dialect. My heart fell.

The only Italians that far north had to be Condottiero mercenaries, contracted to Duke Nicolaus to protect Danuvia. I had let myself become trapped in the Rabenmoss by professional solders; and already there was no going back.

‘These bastard bog dwellers,’ swore one of the Italians. In the still air, he sounded closer than I had thought. His voice had a distinctive roughness, which alerted me to be very wary of him.

I turned my head towards his voice, and my food slipped from the path. I fell into an earthy, wet hollow. The hungry peat engulfed my body up to my hips.

I grasped the roots and stems in the earthy wall above me as I tried to pull myself out. The stalks snapped and broke in my hands. The heavier soil and stones were soon engulfed by the hungry mud. As I sank with them, I felt my panic rise. To calm it, I recalled the time hell had discarded me in a similar highland bog, and prayed.

The setting moon shed a cloud. Its faint beams lit the scabbard of my heavier longsword hanging above my head.

‘Finstar,’ I whispered: ‘Lie down.’

It was a command I had given him before, but then I had been standing at his shoulders and holding his reins, ready to guide him to the ground.

He bent his head towards me. His reins dropped a little. I called to him again, reaching out my right hand. He seemed to grasp my predicament and knelt down on his forelegs. The scabbard hung over the edge of the hole.

I reached up and grabbed the scabbard with both hands. When my grip was secure, I urged Finstar to stand again. He rolled a little as he took my weight with the additional pull of the greedy bog. One foreleg unbent and then the other. The uneven tug of war between the horse and the hungry peat bog stretched my shoulder muscles as I tried to hold on. My grip held, my horse pulled, and together we forced the mire to relinquish its hold on me. The mud fell away from my legs with irritated reluctance. Once free, I dragged myself out of the hollow and hugged Finstar’s neck in silent gratitude. Then I gave thanks to God in wordless prayer.

The mercenaries fell silent. They had heard the quagmire battle across the moss, and peered into the darkness, looking for the source of the noises. I stood still, tense with fear, my arm around my horse’s withers to quieten him. The peaty smell of the bog clung to my body. The night chill crept through my wet clothes.

‘It must have been a bog man,’ a soldier said in Italian. He told the others some Will o’ Wisp tales with a bloodthirsty zest which unsettled the more superstitious ones. Once their thoughts were engrossed with myth, I thanked God again and led my horse on across the bog.

After some time working my way across the mire, I calculated that I should have covered the distance to the Iyver, but my feet had not yet found the firmer ground of the island. I had not got lost along the peat-turfing side tracks. Bewildered, I stood in the darkness, looking for the outline of a building that obscured the starry sky.

Across the bog, the soldiers had ventured onto the path I had taken. When one missed his footing, all leapt back from the mire, unsettled after the bogman tales. With no master to witness their daring, they were not hasty to risk their lives for possibly little gain. They agreed to wait at the sandstone outcrop for dawn’s light to show them the way. A stirring of the air warned me they would not have to wait long.

My horse pulled me forward along the path. We felt firm ground beneath our legs at last: the island I had been seeking. The tension fled from my body after the danger of the crossing. A sapping tiredness replaced it.

After a brief rest, I walked around the edge of the island looking for the Iyver. I found it when a large silhouette blocked out the sky’s low light. I tried the doors of the inn. They were locked and barred.

I did not want to wake the soldiers as well as those within by knocking on the door. Instead, I picked up a pebble and threw it through the view hole in the window shutter.

Arms took me from behind. A hand filled my mouth to silence me. Another gripped my waist to lift me off the ground. The people bundled me into the Iyver stables and threw me into a straw-strewn corner. Someone led in my horse and shut the door. Then the night shade was taken off a coaching lantern near my face. I shied back from the dazzling light.

‘Who are you? What do you want?’

The man was massive: six foot six, broad; pure muscle. I saw beyond his peasant clothes and his unkept black curls and beard; forced to respect. Six other people gathered round him. They had all been sleeping fully clad with their weapons beside them, ready for a fight.

‘Who I am matters little. I…’

He struck my face, throwing me hard against the corner.

‘Facts, not puling, stranger!’

‘Give the traveller a chance to speak,’ said a woman with a hard beauty. She was dressed like a man in riding breeches, and her long black hair was tied back with a fine scarf.

‘If I must, Cara Rea,’ he replied.

Her name brought to mind my early days as a messenger and guide. I had escorted the young Cara Rea shortly after she had earned the right to use the Celtic title Anam Cara, soul friend and advisor. Our journey had taken us through the dangers of Flanders around the time of the Battle of Courtrai. I stood up and gave her a courteous bow.

‘Cara Rea,’ I greeted: ‘Do you not remember me?’

‘No,’ she rebuffed. ‘Who are you?’

Her question surprised me. I had not expected her to forget me after such a perilous journey, despite the intervening years.

‘Gendal the Guide. I took you through the fields of Flanders.’

She drew a deep breath, as if realising her mistake.

‘And what are you doing here?’ demanded the big man.

‘Thiemo sent me to play messenger, to Count Bertram.’

I hoped that if the massive man was the Count, he would not bridle at my not realising it. To my surprise, he paled. His voice dropped low.

‘I am Bertram. What is your message?’

‘Raban is dead.’

Count Bertram shook. Cara Rea paled. She asked me for details. I handed Bertram Raban’s ring and repeated Thiemo’s tale. As they listened, one of their companions shook his head in doubt. He was a brave, stocky man, with bushy red hair whose name I learned later was Gawin.

‘Lies! Duke Nicolaus tries to demoralise us! Throw this bog reject back into the bog he escaped from.’

Cara Rea shook her head. ‘Guide Gendal does not look the sort to lie.’