The John Diaries

If you want to read their other submissions, please click the links.

Introduction

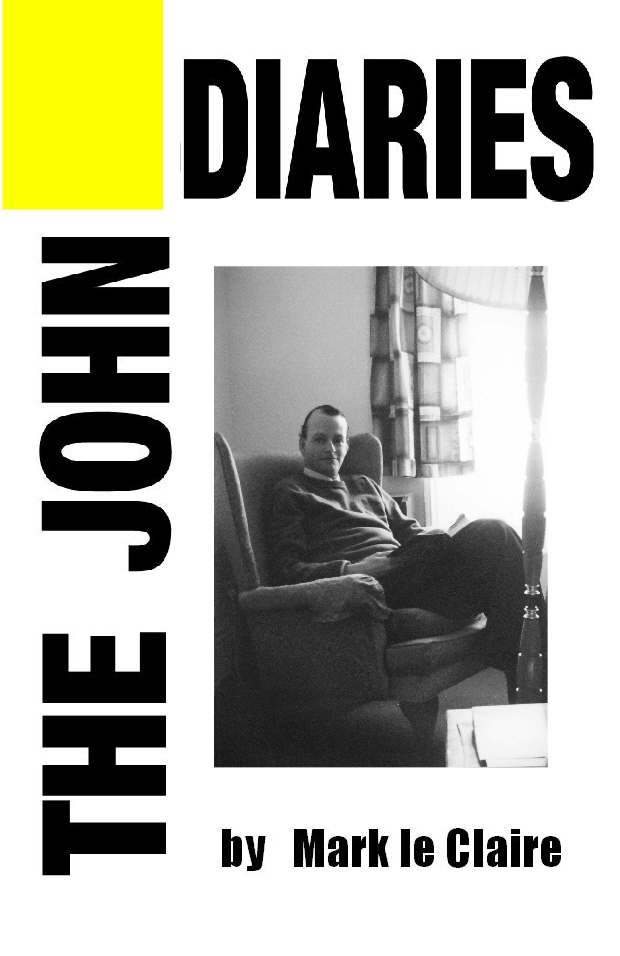

The John Diaries. And yet I referred to him as John Heal, certainly for the first ten years of this diary. Among all the various acquaintances one makes in life there are always a few peculiar characters that one somehow comes to know, people not to be taken seriously, but whom one tolerates and indulges in a condescending sort of way, despite their evident deficiencies. This was certainly the case with John. Most people found him peculiar and a bit of a joke - someone to snigger at behind his back - and I did too. Coming from the land-locked Midlands and having already lived in Folkestone for about ten years, it struck me that sea-side towns seemed to attract more than their fair share of society’s odd balls and misfits, something which I suppose is hardly surprising, given the role sea-side towns have in catering for visitors from elsewhere, some of whom are bound to end up staying. John was another of those slightly odd looking characters one would notice now and then, in John’s case his shambling mid afternoon gait clearly suggesting he was feeling somewhat the worse for wear, doubtless after an extended liquid lunch somewhere, I would knowingly surmise. Fond of a drink myself, this rather predisposed me in his favour. Not that I was in the same category myself, of course. True, I, too, had come to Folkestone and stayed, but I, on the contrary, was not an oddball or eccentric but a talented, artistic person destined for great things; someone who could well afford to accommodate one or two bit part players in his life, like John. Little did I ever dream that one day - stricken with ill health though he was - I would end up needing him more than he needed me.

Tall and gangly, John was fairly normal looking, although there was always something slightly disjointed in his movements, whether tipsy or sober, and a dated look to his habitual black trousers and black shoes, his shirt, tie and pullover, worn with blazer or checked cloth sporting jacket, and with a full length coat in winter. His black hair thinning and teeth in a sorry state, John’s face bore a perennial pasty

1

indoor pallor, and with his dark, grave, unblinking eyes there was a rather spectral air about him, especially at night. Overall, John could hardly have been described as wondrously handsome, although his polite manner and soft spoken, minor public school voice - as well as a droll, ironic sense of humour which he would unexpectedly prove to have - did temper the initial off putting impression he made. He was in his late twenties and I in my early thirties when we finally met, one afternoon on Folkestone’s Leas clifftop promenade. I think I invited him for a drink at the Over-Seas Club, the bar in the nearby flat of my friend, Roy Johnson, with whom I lived. John was an extremely private and reserved person, whose personal life and affairs continued to be something of a mystery even after one knew him. In due course I was to learn that he had come to Folkestone to live with his grandmother, who had died some years earlier. He now lived alone in their flat, which no one ever visited, seemingly, and which was now dustily and airlessly sealed off from the world, as I would be witnessing for myself. Though he obviously had little social contact, I knew John wasn’t a recluse. One saw him out with his shopping bag, or ambling about the town and on the Leas, and neither was he completely friendless, referring, as he sometimes did, to one or two individuals he knew locally. I assumed that he must also have been used to the social proximity of the people in the wine bars he frequented, though whether he interacted with them was another matter. Somehow one pictured him sitting there, his fourth glass of wine at his elbow on the counter, with both he and those in close social proximity around him refraining from striking up any lively conversation. John’s background was genteel, and one got the impression of a person of modest financial independence. He had in fact worked for the Saga holiday company in Folkestone for a while, I learned, but by the time I met him his days of having any such conventional employment or career were over. Although he had his grandmother’s flat to live in, he was in

2

fact living in constrained financial circumstances, and his income - unbeknown to me at the time - consisted of anything he could derive from his own schemes, usually involving pyramid selling, door-to-door canvassing, or the buying and selling of collectables like stamps and postcards, supplemented by support from his long suffering family, in Wiltshire, who several times had to bail him out financially.

Was John autistic? Something was slightly amiss, but one couldn’t quite put one’s finger on it, though like many autistic people he had surprising talents, like remembering people’s telephone numbers, and he had an uncanny memory for past events and conversations. Once, after not seeing him for a long time, I arrived late at his flat to stay the night. We had a two hour conversation over a drink or two and then I went to bed, to wake in the night to hear him pacing about his flat, repeating the whole two hour conversation to himself, word for word, which rather spooked me out at the time. Some years later, by which time I was living in Spain and John was trying to get by on the income from two or three newspaper delivery rounds, and was living a scrimped existence in his flat on a diet of boiled potatoes and biscuits, he had a breakdown and was diagnosed with schizophrenia, after which - with help forthcoming from the state - the questions of his employment and income were finally settled.

When I met John I, too, had no conventional employment and income. Having dropped out of art college, I’d been on my way to Paris to become a renowned artist. I was having an interlude in Folkestone on the way, which, like John’s liquid lunches, had become extended. There I was, thumbing a lift back from earning a few quid strawberry picking over at Challock one day, when I was given a lift by Roy in his Alfa Romeo sports car, with the result that I had pretty soon moved into his flat. I worked as a sign writer in a supermarket, and as a steward on the cross channel ferries, then still not having gone to Paris I

3

decided I’d better start being a painter, a resolve that Roy was happy to assist me with. In return for that, inclusive of accommodation in his flat, and food, and the use of a car - not to mention a room rented for a studio - I did the occasional day’s van driving work for his timber merchant business in Chilham. In short, Roy was supporting me financially, although I tried not to abuse that generosity unnecessarily, and so like John I had very little money. The thing John and I did both have was time - lot’s of time. For years our time was our own, with the freedom to choose whether to go and work on the current oil painting, or go and make door to door charity donation collections, or not. Frequently we chose not and went on an outing and bit of a booze-up somewhere instead, me with a little cash to donate and John putting the lunchtime bill on his credit card and mounting total debt. Or, with the pubs and bars closed for the afternoon by the licensing laws of the time, and while most people - or those fortunate enough to have jobs as Britain emerged from the economically gloomy 1970’s - were gainfully employed at their work, we would while away the time at the Over-Seas Club, me maybe mixing up some cocktails from a bottle of rum that John had brought with him, and with Roy always looking somewhat disgruntled when he came back from his gainful work at Chilham at 6 pm to find us there. The Over-Seas Club was normally open in the evening, when members - i.e. our friends - were free to visit at any time. Behind the bar I enjoyed being the cocktail shaking barman, and the feeling that Roy and I were generous hosts, with any amount of home brewed beer or lager to dispense, along with supermarket spirits, and litre bottles of plonk, lugged back on our regular day trips to France. It was a happy, carefree time for me - I had Roy to rely on, and a circle of friends, and all the time in the world to be an artist. I also had this odd drinking pal called John Heal, who had come out of his shell a bit since I'd first met him and was now being quite sociable. Everyone I knew thought he was very peculiar, but I

4

got on with John alright - why, I could practically consider him a friend of mine, couldn’t I?

Yes, it was all good fun we were having - and pretty innocent fun at that - and meanwhile I continued with my diary, which I’d started a few years earlier. I’d been inspired to begin it after reading the journals of Evelyn Waugh. I knew my diary wouldn’t be recording any stylish high society events like his, but something in Waugh’s writing style - clear and objective and briskly matter-of-fact - and the also conventionally literate style of other English novelists I’d been reading, like George Orwell and Aldous Huxley – Cyril Connolly, too, and his Palinarus - influenced my diary writing and also the style and tone of my future novel, Vapour Trails in the Blue. Aside from a love of Scott Fitzgerald’s doomed romantic writing from the twenties, I’d also read American authors prominent during the 'sixties of my youth, like Mailer, Heller, Roth and Vidal, and in fact my principal cultural influence had always been the nineteen sixties; its album music, fiction and poetry, all culminating in that decade’s counter culture, as expressed in the magazines, Oz and the International Times, heavily influenced as that whole movement had been by the 'fifties beat poets and writers - Ginsberg, Boroughs and Kerouac – still revered as the trail blazing, iconic heroes, or anti heroes. If I hadn’t become an out and out hippy myself, I retained hippy-ish ideals, and when I began my diary I decided that if it wouldn’t be recording any stylish high society events, or in fact be recording any other notable worldly matters and events that might feature the laudable exploits and achievements of myself, it would simply have to record the events from a lowlier strata of society - my localised arty and hippy-influenced world - but still written in a studied, educated literary way - more Aldous Huxley than Henry Miller - aspiring, as far as my abilities went, to what Connolly had referred to as a mandarin rather than vernacular style.

5

While writing my diary I always felt acutely conscious, as most of us surely do, at times, of the fact that my life hadn’t been bound to take this particular path I was writing about. I could have become a celebrated artist, or an odd job man, or magazine editor, or probation officer, or have been on probation myself, or have been and done any one of a million other things. This thought only reinforced the detachment with which I wrote, a detachment which might seem a little heartless to the reader, but even if had taken a different path, I would still have viewed it in exactly the same way, and I suppose it is this fatalistic outlook on life that has always prevented me from changing direction. What is certain is that you can’t change the past, and we’re all bound to take a path of some sort, and afterwards all we have is the memory, and perhaps a few photographs, and sometimes a diary too. So is this the sole reason to keep a diary in the first place - to help recall the past? Without a memory like John’s, it can be hard to remember what happened last week, let alone the events of a decade ago. In addition to that primary function, though, a diary does help to clarify the diarists thoughts and come to a decision on things. At the time of writing, a diary can almost seem like a best friend, someone - or thing - to confide in and get things of your chest. Then there is the question of posterity and the prospect of it one day being read by someone else, one's descendants, maybe, or a wider readership - the great reading public, no less! a thoughts which does cross diary writer’s mind from time to time, and which is likely to prod that person’s ego and vanity into watchfulness. We all like to present our best - or preferred - side to the world, and a diary let’s you to do that. The diarist enjoys the luxury of recording and judging everything from his or her own personal point of view, with no one around to argue with you. This will justify my life, is the diarist's secret hope. Vanity is usually the ultimate reason for keeping a diary, which is doubtless true in my case. The reader may wonder what I had to be vain about - unrenowned, financially dependent and hangover incapacitated self professed artist that I was - and I, too, knew full well that the often unenthralling doings of my younger or not-so-young years were hardly likely to arouse much envy or admiration, but I fully expected to be compensated for this one day, when my diary did, indeed, become a record of my later fulfilled, successful, glamorously interesting life, at which point the inconsequential earlier years would be looked on not with disdain but with compassion and understanding - approval, even. See, how he matured and put all that behind him and went on to great things! people would murmur. Amazing, isn’t it, what those rich, talented, celebrated people can get away with?

So the years rolled on, with me continuing to record my life, rich and famous artist (or writer) or not. As well as Waugh - and especially since becoming a diarist myself - I have enjoyed reading various other people’s dairies, including, in whole or in part, those by WNP Barbellion, George and Weedon Grossmith (authors of the fictional Charles Pooter diary), Chips Channon, Virginia Wolf, Anais Nin, Joe Orton, Alan Clarke and Gladys Langford. I recently read A Life Unknown, an investigative account by Alexander Masters of a diary that was found in a skip. It was from a diary that was a world record fourteen million words long. Mine continued to grow, but it was never in that league. It might be over a million words long, I calculated one day, when I was idly pondering on what might, in fact, be destined to become of my own diary. By then I was in my sixties - probably it was sometime after the failure of Vapour Trails in the Blue - when the terrible truth dawned on me. . . that my diary, too, was probably destined for the bin.

7

Unless I did something about it, I could clearly see. Among those diaries I’d read and enjoyed, some of their authors were just about as little known as I was, like Gladys Langford, or the Grossmith’s kindly, fictional Pooter, of Highgate Hill, whose very obscurity and deluded self importance was the whole point of the diary, something which exposed the fallacy of my reasoning about my own diary’s worth. I hadn’t put my past life behind me and gone on to greater things, but so what? Couldn’t my diary still be published as it stood? In fact, I had already published a selection of my diaries, covering the years when I was writing and publishing Vapour Trails in the Blue, but as far as the bulk of it went I knew it couldn’t be published in its entirety; a longer edited selection was called for, and having known John for thirty years, from the age when I was thirty-three to sixty-three – the principal chunk of anyone’s life – I decided to publish a selection of my diaries from that period, consisting of every diary entry with any reference to John in it. I resolved to be faithful to this idea and include every such entry, whatever the context or subject matter. It has meant I’ve had to include some entries that I would rather have left out - usually containing some painful, embarrassing personal detail - and leave out others that I would have liked to include, that probably showed me in a better light. To this end, I have used my acquaintanceship - my friendship with you, John - to publish this present volume. I don’t know what you would have had to say about it - me going and blowing your privacy, like this - but even when you were here, I would like to think that you wouldn’t have minded so much, after all, or would at least have forgiven me. I hope you do, John, and that you accept my apology . As for anyone else, who considers it plain wrong of me to have gone and done such a thing, I’ll just have to plead guilty, as charged, and live with the shame of it and their censure.

Mark le Claire, Belsize Park, 2021

Comments

The John Diaries

I had no space to include any of the actual diary.