The Tenth Floor, A Christmas Parable

When 10 year-old Jill meets an elderly man in a wheelchair who must get to the top floor of her apartment complex, she has no idea that their journey up ten stories will evolve into an adventure of a lifetime.

With their arms limp and shoulders slumped, not even the bundling of winter clothing could conceal the disappointment of the ten-year-old girl and her mother as they stood at the aisle’s endcap, gaping at four empty shelves.

“I’m… I’m sorry, Jill,” her mother stammered. “The ad said they’d have ’em in stock. The only store in the entire world, as far as I can tell.”

Jill sniffled jerkingly and motioned to the blank display before smacking her open palms back to her sides.

Above the shelves, a banner colored in the shades of the season—reds, greens, golds—fluttered under a heater vent, its left corner hanging limply where an eyelet tore loose. “Last Chance, 1970! Christmas Eve Sale!” it declared alongside the picture of a Super Fashion Princess Doll in its pyramid-shaped box. However, this image above the barren shelves remained the only indication of a pyramid.

“They lied,” Jill accused, speaking directly to the empty shelves, as if they could answer for the sin. “They lied to children, to get us here so we’d buy something else. Something we don’t want.”

Ashamedly, Jill’s mother nodded. “I just…” she paused and cleared her throat, “this… this was my last hope to find one, baby.”

“The world is awful!” Jill shouted at the empty shelves.

Jill’s mother tried to shake her head but couldn’t muster it in the moment. She reached for her daughter’s shoulder and said, “I’m sorr—”

But Jill jerked away.

“Daddy’d figure it out,” the ten-year-old shot at her. “I wish he was here.”

Jill’s mother deflated at the words, and she blinked back a tear. “Well, he’s not here,” she forced. “And you could stand to watch your tone,” she added.

Her daughter sniffled again with a harsh nod. “I’m sorry,” she whispered. “But maybe,” she began and hesitated before continuing, “but maybe Santa…”

With that, her mother’s shoulders sank even lower. “They’ve been impossible to find for months,” she confessed, and followed in almost a whisper, “I don’t even think Santa could find one.”

A last, shuddering whimper tried to fight out of the girl, but she kept it down. Jill then buttoned her double-breasted coat—a pink hand-me-down in the style of Jackie Onassis—and pulled a matching beret over her ears. She then bent slightly at the knees to grasp the bags at her feet before turning and heading for the exit of the shopping center. Her mother likewise buttoned her fur-collared coat and picked up her load, twice as many bags at her sides, and followed her daughter towards the street.

Glassy ice covered the ground and hung from trees following a short rain that fell while the two ladies shopped, and with the sun setting in the interim, the temperature fell to below freezing. Steam billowed from a sewer grate, and ice melted and then reformed under the bulbous gas lamps, since converted to electric, lining the sidewalk.

Jill stepped onto the walkway, and her lace-up boots skidded and the flares of her jeans fluttered as she rotated on the slick cement.

Her mother lurched to grab Jill from falling, but her own knee-high boots almost slid from under her, sending her arms flailing and the pleats of her dress fluttering.

“Oh my gosh!” Jill breathed to her mother, reaching out with a bag dangling from her wrist.

Jill’s mother helplessly reached for her also, not quite making it. She inched towards her daughter until they grasped fingertips and pulled one another closer across the ice, the steam of their breath swirling before their faces.

“What happened?” Jill asked.

“Ice storm!” her mother gasped.

Holding hands while negotiating their bags, the pair inched down the sidewalk to the curb.

Jill’s mother spotted a taxi slowly nearing them with its light glowing above the windshield. She waved, and the driver waved back and flipped off his light as he pulled to the curb.

With a surefootedness unhampered by baggage, though, a grey-haired man and a makeup-painted woman whisked past. The tails of their black trench coats fluttered and then settled as the woman grabbed the taxi’s doorhandle and jerked it open. The man never looked back as he slid his fedora over his face while ducking under the roof, but the woman momentarily met the eyes of Jill’s mother before following him inside.

“What?” Jill’s mother screamed, throwing her hands in the air and immediately yelping as her feet threatened to slip from under her.

The cab trailed a wisping cloud of exhaust as it pulled past, the two occupants averting their eyes from the mother and child left out in the cold.

“Back-stabbers!” Jill’s mother screamed in their wake.

Jill similarly disapproved with a staccato of “Awful! Awful! Awful!” at the disappearing cab. Yet, with little more hesitation than that, Jill turned and waved wildly to a second yellow cab that crunched to a stop in front of them. The little girl nodded a hard nod of approval as the car’s trunk popped open even before it settled to a halt.

“Good job, baby,” her mother breathed and continued to inch forward, albeit faster this time. She took the bags from her daughter and tossed them into the trunk while Jill opened and waited next to the rear door, her teeth clattering in the cold. Her mother then slammed the trunk and dove into the backseat with Jill quick to follow.

The cab’s interior didn’t feel much warmer than outside. Nevertheless, it smelled of fresh coffee, and the sound of Smokey Robinson and the Miracles singing “Jingle Bells” brought some comfort against the temperature. The Ford’s front defroster whirred hard to keep the windshield clear, so that from front to rear, the windows gradually faded into fog and flecks of ice until they became impenetrably opaque behind Jill’s head.

“Hey, how ya doin’ on this Christmas Eve?” the cabbie asked, turning slightly in his seat, his face almost hidden beneath a set of bushy muttonchops that extended into a similarly colored turtleneck.

“Can’t complain too much,” Jill’s mother laughed, unhooking the top button of her jacket. “Cold, but good!”

“Yeah, I guess I picked the wrong shift,” the cabbie chuckled before stealing a drink from his steaming mug cap. “Where to?”

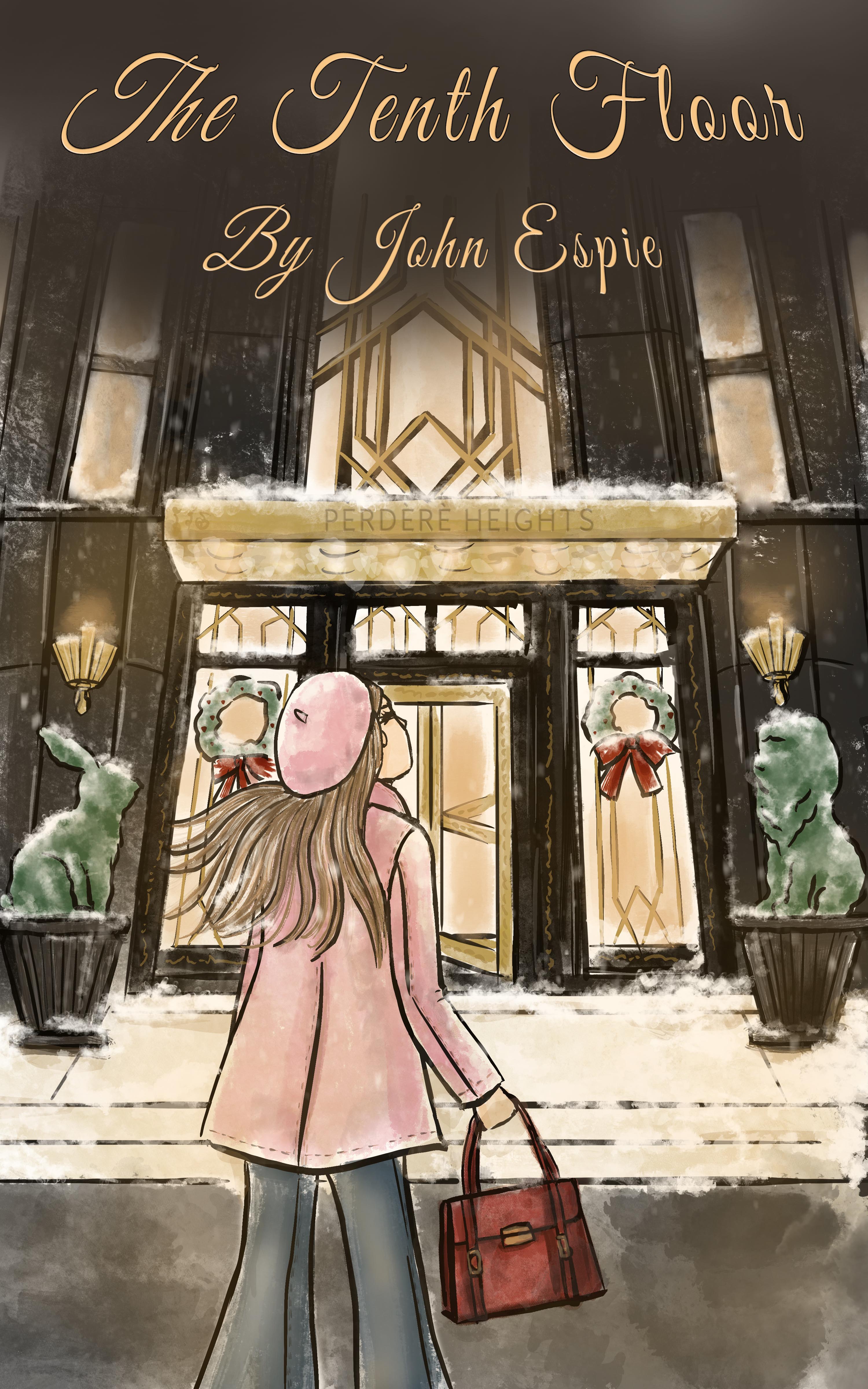

“The Perdéré Heights, please.”

“You got it,” the cabbie said as he slipped the column shifter into drive and the engine rumbled his taxi into the street. “You like that place?”

“I’d like to get out of that place,” Jill’s mother sighed while unconsciously withdrawing a tiny cross pendant from her jacket and kissing it. “It gives me the creeps, but anything better seems impossible with the way rent is these days.”

“Yeah, and it’s only gonna get worse,” the cabbie grumbled, glancing left and right at the blare of an inexplicable horn. “I hear the top floors are nice, though.”

“That’s what they say,” Jill’s mother replied, then rubbed her palms together and blew into them. “Can you turn the heater up a bit?”

“Sorry,” the cabbie said, patting the dashboard, “but the old girl needs to give it all to the defroster or I won’t be able to see out. I think it’s to do with the humidity or somethin’.”

Jill’s mother nodded jerkily and gave Jill a sideways glance with a shrug.

“I’m good, mom,” Jill said with a forced smile as she pinched the collar of her jacket around her throat. “It’s only a short drive. We walk it in the summer, remember?”

The little girl then turned her attention outside. Through the window’s condensation, the high rises were nothing more than blobs whose lights dispersed into each other like drips of watercolors on a matte canvas. Jill wiped a swathe with her arm, and the blobs suddenly sharpened into the flickering pinpoints of windows, and the blinking letters of neons, and the steady spotlights of billboards. The sidewalks appeared almost devoid of people, except for a few doormen under awnings, shivering in their winter coats. Some wore boots, but most were slipping and skidding in their patent leather wingtips as they rushed to cab doors, or grabbed bags from trunks, before escorting their guests inside.

Jill pressed her cheek to the window, shocking with its impossible coldness, and she watched her breath stream downward from her nose and across the glass. Her attention shifted outside once more when their apartment building came into view, just as “Jingle Bells” ended and John Lennon’s voice began to sing about how we all shine on, and she recognized the hunched shoulders of her superintendent as he cast salt onto the sidewalk.

Just like every other time when she approached their apartment, Jill lowered her eyes to the rows of hedge topiary at the base of the building, formed into barely recognizable lions and rabbits and dogs. She then counted the windows from the ground level up, hesitating at the fourth story to spot her own apartment, but the art deco face of the building refused to relent in the repetitiveness of its geometry, one window indistinguishable from the next. She continued counting all the way to the tenth floor—the last floor—now needing to contort her neck to see that high, where a window washing crane dangled its platform over the side like a lifeboat swaying off the flank of an enormous cruise liner.

Jill strained her neck in an effort to soak in the top stories for as long as she could. She’d heard the gossip, mumbled in countless elevator rides, about how the uppermost floors were luxury apartments rented by the unthinkably rich. Some of the apartments were former ballrooms, and so huge they occupied an entire side of the building with vaulted ceilings that encompassed the full height of a second floor. Or, at least, that’s what the folks from the lower levels believed.

Jill fantasized about what the tenth floor must be like, of the people who could afford to live that high, and how it must be so much better than her awful life. I bet there’s a little girl up there, she thought wistfully, and she’s got a custom-made dollhouse, with a picket fence and a horse stable, and it’s full of Super Fashion Princess Dolls...

With that vision in her mind, and while still gazing upward, Jill spotted a single star peek through the clouds, and she squeezed her eyes shut. “I wish, I wish with all my might,” she whispered, “that I could be on the tenth floor tonight…”

The Ford’s brakes squealed, and the cab ground to a stop next to the old hunch-backed super in his frayed parka. He offered a toothless grin as he paused his shoveling to glance through the side-window, and he almost stepped forward to open the door… until the focus of his eyes shifted and said that he recognized Jill as a lower floor tenant. With that, his lip curled under a thick mustache as he snorted a glob of snot into his sinuses, and he thrust the shovel into the corrugated trashcan and cascaded another wave of salt against the side of the Perdéré.

While Jillian’s mother fumbled with a crumple of cash from her purse, the cabbie released the rear trunk lid, its rise barely a shadow through the fogged rear window.

Jill lifted the door handle and pushed without effect. She threw her shoulder into it, and the seam released with a pop that nearly sent her tumbling into the cold that stung her cheeks. “Oh, my gosh!” she gasped, “I guess the heater was working!” Tentatively, Jill stepped over the gutter and onto the sidewalk before turning and offering a shivering hand to her mother, who took it and pulled herself out of the cab.

Jill’s mother then slammed the door and carefully stepped around to the trunk, the thick salt of the sidewalk crunching to powder under her feet. As Jill’s mother stepped into the unsalted gutter, though, her shoe slipped, and she grasped for anything to break the fall, one hand slapping the trunk lid down to its latch a moment before she landed face-first in the slush of the street.

The old Ford’s engine revved and shrouded Jill’s mother in a mist of muffler steam as the cab pulled into traffic.

“No, stop!” she screamed, struggling to rise before slipping back to her knees, “Our bags— stop!”

At first Jill rushed to cover her mother’s legs, her skirt pleats having flipped up to reveal winter leggings, but then a grip of horror seized her with the realization that their Christmas presents were accelerating down the road. Jill frantically waved at the foggy rear window, yet the cabbie was already off to his next fare.

Jill’s mother struggled upright and ran after the cab, slush flinging off her limbs as she waved, and then she shouted over her shoulder, “Go upstairs— I think I can catch him at the light!”

“Oh, Mom...” Jill groaned, watching her continue down the street, occasionally saving herself from another slip on her heeled boots. Jill glanced back at the sludge of mud and crushed ice where her mother’s purse lay ruined on the asphalt. She picked it up by the strap, shaking off a few gobs of mud, and then turned to find herself staring into the narrowed eyes of her building’s superintendent.

He slowly shook his head, snorted in another wad of snot, and returned to digging his shovel into the trashcan.

“Thanks for the help,” Jill mumbled as she trudged past the barely recognizable animal hedges and into the grand entrance of her home.

The Perdéré Heights’ art deco appointments in black lacquers, and red drapings, and gold platings, and various contrasting species of parquet woods belied its more ordinary standing as an apartment complex. Previously known as the Perdéré Grand Hotel, it never recovered from the fall of 1929, and World War II eventually snuffed out its remaining financial reserves. In that conflict’s aftermath, the city subsidized the hotel into full-time apartments as a means of luring skilled veterans for its post-War boom.

Yet the lobby, etched in time as an artistic landmark, remained as elegant as ever.

Wrapping around a permanently empty check-in counter, the grand staircase wound the height of one floor upwards to a viewing platform along the window front, and then the stairs continued their graceful spiral another story skyward until they disappeared into the round and square geometries of ceiling tiles that resembled the golden bursts of a thousand suns. Back at ground level, and opposite the staircase, awaited the Perdéré Grand’s opening day masterpiece: a single elevator with its sliding, nickel-plated door exquisitely etched into an exploding sun to match the ceiling tiles into which it ascended.

In the 1920s, Architectural Digest hailed this elevator as a marvel of both functionality and art. Its “functionality” would soon be called into question, however, as the local newspaper reported that the hotel’s staff often joked that, if the elevator managed to bring a new guest up to their floor, they were doomed to never leave it again.

And, thus, on this Christmas Eve five decades beyond the Perdéré Grand Hotel’s opening night, Jill found herself staring at a hand-scribbled “out-of-order” sign taped to the most awe-inspiring door she had ever encountered.

Jillian’s shoulders wilted, and she dropped her mother’s ruined purse to her feet. Feebly, she pushed the “up” button, unlit and unresponsive, and groaned aloud.

Next to her, a throat cleared into a judgmental harumph, and Jill glanced downward to an old man so small, he seemed to be swallowed by the wheelchair in which he sat. He wore a brown suit with a wide lapel and flared pants. A paisley tie offered the only color on his body, with the exception of his tortoise shell glasses. While his hair probably started the day combed over his bald spot, it currently stood at end, as if he’d been attacked by an electrical cord.

The old man cocked a brow at her and then motioned to the grand staircase with a hand that trembled with age. “If you think you’ve been betrayed,” he said in a gravelly voice, “how do you expect me to feel?”

Jill winced at the sight of the stairs, her Girl Scouts’ creed of To help people at all times enhancing her concern over an elderly man in a wheelchair… but then the wince was also a bit about herself needing to climb those stairs as well. “I’m sorry,” she said to him, her voice trailing the last word, as if this would make the sentiment sound more real. “Maybe I could help? I live on the fourth floor.”

The old man harumphed again and shook his head at the closed elevator, beaming at it with eyes that would have melted the nickel if only for a bit more effort. “I’m going all the way to the top,” he growled.

Jill’s mouth gaped open a bit. “The tenth floor?” she asked.

The old man shifted his body sideways and downward as he lifted a previously unseen package to his lap: a pyramid wrapped in green paper with red ribbon bordering the edges and tied in a fancy bow at the tip. “I’ve got a gift to deliver,” he said, “to a little girl. Has to be tonight.”

Jill’s eyes widened at the sight of the pyramid-shaped box, and she crouched alongside his wheelchair to get a better look at it. “A little girl’s on the top floor?” she asked with anticipation. “And this is for her? For Christmas?”

The old man looked over each of his shoulders, his chin trembling at the end of both glances, and he harumphed again. “Sounds like an echo in here.”

“Well, she’s gotta get it!” Jill nearly shouted while jumping to her feet. “This has got to get delivered!”

“And how’s that gonna happen?” the old man breathed, motioning to the broken elevator, and then throwing his thumb at the stairs again. “Those don’t look any better, at least for me and this contraption.”

“Perhaps…” Jill thought for a moment, biting her lower lip and then perking up, “Maybe you could hand it to me, and I could run the gift up for you?”

The old man smiled subtly at the thought. “That’s a nice offer, kid,” he said, “but I need to deliver it myself. It’s a personal thing…”

Without hesitation, Jill nodded and patted his arm. “I understand,” she said. “Doing a proper job matters.” She then trotted to the bottom of the stairs and looked up them, thinking to herself. She turned to the old man and asked with a raised voice, “I’m sorry, but… can you…”

“Am I stuck in this thing fulltime?” he asked.

Jill nodded.

“No,” he said, “I can walk. Just not good.”

“So, maybe I can help you up the stairs?” she asked. “I could take your arm, and we could climb each flight together, one by one. Between each floor, I could come back for your wheelchair while you rested.”

The old man chuckled to himself, but his eyes lit up a bit. “All the way…” he said, taking off his glasses and incredulously pointing one of its temples at the ceiling, “to the top?”

“My dad says that the longest march is conquered one step at a time,” she replied matter-of-factly. “And he also says that if there’s a will, there’s a way. So if you’ve got the will, I’ve got the way.”

The old man rotated his wheelchair towards the stairs and grinned at her, package resting on his lap. “I suppose he’s also the one who says that ‘doing a proper job matters?’”

Jill nodded fervently, again without hesitation.

“You know, I like you, kid,” the old man breathed and pointed his glasses at her, “but shouldn’t you be getting home?”

“My mom told me to ‘go upstairs,’” Jill said, alighting the first step of the grand staircase while outstretching her hand to the old man, “so let’s go upstairs.”

The old man glanced at the present in his lap. He pursed his lips with determination and nodded to himself. “Alright,” he said, impetuously thrusting his eyeglasses back onto his face. “A man should test his mettle sometimes. Let’s do it.”