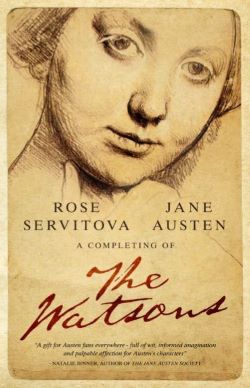

The Watsons

Chapter One

The first winter assembly in the town of Dorking in Surrey was to be held on Tuesday, October 13th and it was generally expected to be a very good one. A long list of county families was confidently run over as sure of attending and sanguine hopes were entertained that the Osbornes themselves would be there.

The Edwardses’ invitation to the Watsons followed, of course. The Edwards were people of fortune, who lived in the town and kept their coach. The Watsons inhabited a village about three miles distant, were poor and had no close carriage, and ever since there had been balls in the place, the former were accustomed to invite the latter to dress, dine and sleep at their house on every monthly return throughout the winter.

On the present occasion, as only two of Mr Watson’s children were at home, and one was always necessary as companion to himself, for he was sickly and had lost his wife, one only could profit by the kindness of their friends. Miss Emma Watson, who was very recently returned to her family from the care of an aunt who had brought her up, was to make her first public appearance in the neighbourhood. Her eldest sister, Elizabeth, whose delight in a ball was not lessened by ten years’ enjoyment, had some merit in cheerfully undertaking to drive her and all her finery to Dorking on the important morning.

As they splashed along the dirty lane, nestled together in the old chair, Emma was eager to learn more about her dear siblings, the friendliness of neighbours and the likelihood of agreeable gentlemen attending the ball. Elizabeth, wishing to oblige, delighted in the opportunity to instruct and caution her inexperienced sister.

“I dare say it will be a very good ball and among so many officers you will hardly want for partners. You will find Mrs Edwards’ maid very willing to help you with your hair but whatever you do, do not permit her to place flowers in it. I made this error once and appeared as the Hanging Gardens of Babylon for the evening. It is almost winter now so you should be safe. I would advise you to ask Mary Edwards’ opinion if you are at all at a loss for she has very good taste. If Mr Edwards does not lose his money at cards, you will stay as late as you can wish for; if he does, he will hurry you home perhaps, but you are sure of some comfortable soup.”

Emma nodded to indicate she was taking note of Elizabeth’s advice.

“I hope you will be in good looks. I should not be surprised if you were to be thought one of the prettiest girls in the room. There is a great deal in novelty. Perhaps Tom Musgrave may take notice of you but I would advise you by all means not to give him any encouragement. He needs very little and generally pays attention to every new girl. He is a great flirt, however, and never means anything serious.”

“I think I have heard you speak of him before,” said Emma. “Who is he?”

“A remarkably agreeable young man of good fortune, a universal favourite wherever he goes, first and foremost with himself and then with any young ladies present. Most of the girls hereabout are in love with him, or have been. I believe I am the only one among the ladies to have escaped with a whole heart and yet I was the first Mr Musgrave paid attention to when he came into this country six years ago. Very great attention did he pay me too but he never captured my heart.”

“And how came yours to be the only cold one?” said Emma, smiling.

“There was a reason for that,” replied Elizabeth, changing colour. “I have not been very well used among them, Emma. I hope you will have better luck.”

“Dear sister, I beg your pardon if I have unthinkingly given you pain.”

“When first we knew Tom Musgrave,” continued Elizabeth, “I was very much attached to a young man of the name of Purvis, a particular friend of Robert’s, who used to be with us a great deal. Everybody thought it would have been a match.”

Emma, unsure how best to respond, remained silent but her sister after a short pause went on:

“You will naturally ask why it did not take place and why he is married to another woman, while I am still single. But you must ask her, not me; you must ask your sister Penelope. Yes, Emma, Penelope was at the bottom of it all. She thinks everything fair for a husband. I trusted her. She set him against me, with a view to gaining him herself and it ended in his discontinuing his visits and soon after marrying somebody else. Penelope makes light of her conduct but I think her treachery very bad. I shall never love any man as I loved Purvis but that is not to say that I shall never love any man. I hope I shall, for I must. But Tom Musgrave – why he should not be mentioned with Purvis in the same day!”

They rode on for a few minutes in near silence, Elizabeth occasionally pointing out some feature in the landscape and enquiring of Emma if she remembered it. The concern with which Emma felt in relation to the previous discussion, however, meant that she must return to it and with furrowed brow began,

“You quite shock me by what you say of Penelope,” said Emma. “Could a sister do such a thing? Rivalry, treachery between sisters! I shall be afraid of being acquainted with her. But I hope it was not so. Appearances were against her, I am sure. Loyalty and unselfishness is what I think when I think of family; those happy beliefs keeping me warm all these years. A family may be crossed by circumstance or by others but not by each other. There is no stronger bond.”

“You do not know Penelope. There is nothing she would not do to get married. Do not trust her with any secrets of your own. I never shall again. She has her good qualities but she has no faith, no honour, no scruples where she can promote her own advantage. How surprised you look Emma. I do not wish to alarm you and yet I wish with all my heart that she was well married. I declare I had rather have her well married than myself.”

“Than yourself! Yes, I can suppose so. A heart wounded like yours can have little inclination for matrimony.”

“Not much indeed, but you know we must marry. I could do very well single for my own part – a little company, a pleasant ball and a glass of mead every now and then would be enough for me. But our father cannot provide for us and I dread relying on the good humour and fortunes of our brothers. No, we must marry, if at all possible, for it is very bad to grow old and be poor and laughed at.”

Their father’s old mare, Lady Macbeth, clanked and clanged along the bad road, instinctively avoiding all the worst parts. The girls were, therefore, thrown about less often than they might have been by a more ambitious horse.

“Not that I can ever quite forgive Penelope, but for all her meddling in other people’s affairs, she has had her own troubles,” continued Elizabeth. “She was sadly disappointed in Tom Musgrave, who afterwards transferred his attentions from me to her and of whom she was very fond, but he never means anything serious. When he had trifled with her long enough, he began to slight her for Margaret and poor Penelope was very wretched. I am glad you were not with us then for she screamed and scolded dawn till dusk.”

Emma’s spirits continued to sink at such contrary domestic scenes to those she had long imagined. Elizabeth continued,

“And since then Penelope has been trying to make some match at Chichester. She won’t tell us with whom but I believe it is a rich old Dr Harding, uncle to a Miss Shaw she goes to see. She has taken a vast deal of trouble about him. When she went away the other day, she said it should be the last time and said it with such a look that I could not help but feel sorry for poor Dr Harding. His fate is sealed, whether he is aware of it or not. I suppose you did not know what her particular business was at Chichester, nor guess at the object which could take her away from Stanton to Miss Shaw’s just as you were coming home after so many years’ absence.”

“No indeed, I had not the smallest suspicion of it. I considered her engagement to Miss Shaw, just at that time, as very unfortunate for me. I had hoped to find all my sisters at home – and would have assumed that they would have been unless something of a very urgent nature took them away – to be able to make an immediate friend of each.”

“Perhaps in her eyes it was very urgent, for I suspect the doctor to have had an attack of asthma and that she was hurried away on that account. It would never do to lose a husband before he had become one. The Shaws are quite on her side – at least, I believe so, but she tells me nothing. She professes to keep her own counsel.”

“I am sorry for her anxieties,” said Emma; “but I do not like her plans or her opinions. I shall be afraid of her. She must have too bold a temper. To be so bent on marriage, to pursue a man merely for the sake of situation is the sort of thing that shocks me. I cannot understand it. Poverty is a great evil but to a woman of education and feeling it ought not, it cannot, be the greatest. I would rather be teacher at a school (and I can think of nothing worse) than marry a man I did not like. Anything is to be preferred or endured than marrying without affection.”

“I would rather do anything than be teacher at a school,” her sister said, laughing. “I have been at school, Emma, and know what a life they lead. You never have. I should not like marrying a disagreeable man any more than yourself but I do not think there are many very disagreeable men. I think I could like any good-humoured man with a comfortable income. The more comfortable his income, the more good-humoured I shall find him. I suppose our aunt brought you up to be rather refined.”

Elizabeth smiled while Emma, eager to defend her upbringing, said, “Indeed I do not know. My conduct must tell you how I have been brought up. I am no judge of it myself. I cannot compare my aunt’s method with any other person’s because I know no other. She raised me as she judged best. Perhaps I am a little reserved from want of company.”

“But I can see in a great many things that you are very refined,” continued Elizabeth. “I have observed it ever since you came home and I am afraid it will not be for your happiness. Penelope will laugh at you very much.”

“That will not be for my happiness, I am sure. If my opinions are wrong, I must correct them. If they are above my situation, I must endeavour to conceal them but I doubt whether ridicule… Has Penelope much wit?”

“Yes. She has great spirits, or rather cunning.”

“Margaret is more gentle, I imagine?”

“Yes, especially in company. She is all gentleness and mildness when anybody is by but she is fretful and irritable among ourselves. She loves gossip. It is what she lives for. Poor creature! She is possessed with the notion of Tom Musgrave’s being more seriously in love with her than he ever was with anybody else and is always expecting him to come to the point. This is the second time within this twelvemonth that she has gone to spend a month with Robert and Jane on purpose to encourage him by her absence. I am sure she is mistaken and that he will no more follow her to Croydon now than he did last March. He will never marry unless he can marry somebody very great – Miss Osborne, perhaps, or something in that style.”

“Your account of this Tom Musgrave, Elizabeth, gives me very little inclination for his acquaintance.”

“You are afraid of him. I do not wonder at you.”

“Not afraid, indeed. I dislike him.”

“Dislike Tom Musgrave! No, that you never can. I defy you not to be delighted with him if he takes notice of you. I hope he will dance with you and I dare say he will, unless the Osbornes come with a large party and then he will not speak to anybody else.”

“He seems to have most engaging manners!” said Emma. “Well, we shall see how irresistible Mr Tom Musgrave and I find each other. I suppose I shall know him as soon as I enter the ball-room. He must carry some of his charm in his face.”

“You will not find him in the ball-room, I can tell you. You will go early, that Mrs Edwards may get a good place by the fire, and he never comes till late. If the Osbornes are coming, he will wait in the passage and come in with them.”

“Then I shall be surprised if he notices me at all.”

“I should like to look in upon you, Emma, for I believe it will be a marvellous ball and the neighbourhood, for not having had one for months, will be inclined to find it excellent. If it was only a good day with my father, I would wrap myself up as soon as I had made tea for him and James should drive me over so I should be with you by the time the dancing began.”

“What! Would you come late at night in this chair?”

“To be sure I would. There, I said you were very refined and that’s an instance of it. I care not a jot in what fashion I appear.”

Elizabeth laughed again and Emma, for a moment, made no answer, then at last she said, “I wish, Elizabeth, you had not made a point of my going to this ball. I wish you were going instead of me. Your pleasure would be greater than mine. Your laughter more deserved. I am a stranger here and know nobody but the Edwardses. My enjoyment, therefore, must be very doubtful. Yours, among all your acquaintance, would be certain. It is not too late to change. Very little apology could be requisite to the Edwardses, who must be more glad of your company than of mine, and I should most readily return to my father and should not be at all afraid to drive this quiet old creature home. Your clothes I would undertake to find means of sending to you.”

“My dearest Emma,” cried Elizabeth, warmly, “do you think I would do such a thing? Not for the universe! But I shall never forget your good nature in proposing it. You must have a sweet temper indeed! I never met with anything like it! What a fine thing to learn, at last, that I have a sister, without trick or self-interest. And would you really give up the ball that I might be able to go to it? Believe me, Emma, I am not so selfish as that comes to. No, though I am nine years older than you are, I would not be the means of keeping you from being seen. You are very pretty and it would be very hard that you should not have as fair a chance as we have all had, to make your fortune. No, Emma, whoever stays at home this winter, it shan’t be you. I am sure I should never have forgiven the person who kept me from a ball at the age of nineteen.”

Emma expressed her gratitude and Elizabeth put her arm around her and gave a short and fond squeeze.

“The next turning will bring us to the turnpike. You may see the church-tower over the hedge and the White Hart is close by it.”

Such were the last sounds of Elizabeth’s voice, before they passed through the turnpike-gate and entered on the pitching of the town, the jumbling and noise of which made further conversation most thoroughly undesirable. Old Lady Macbeth trotted heavily on, wanting no direction of the reins to take the right turning and making only one blunder, in proposing to stop at the milliner’s, before moving on towards the correct row of houses. Mr Edwards lived in the best house in the street and the best in the place, if Mr Tomlinson, the banker, might be indulged in calling his house at the end of the town, with a shrubbery and sweep, in the country.

As they approached it, Emma could see that Mr Edwards’ house was higher than most of its neighbours, with four windows on each side of the door, the windows guarded by posts and chains and the door approached by a flight of stone steps.

“We have almost arrived,” said Elizabeth, “and by the market clock, we have been only thirty minutes coming, which is quite a wonder when one considers Lady Macbeth’s reluctance to move at all. Is it not a nice town? The Edwardses have a noble house, you see, and they live quite in style. The door will be opened by a man in livery, with a powdered head, I can tell you.”