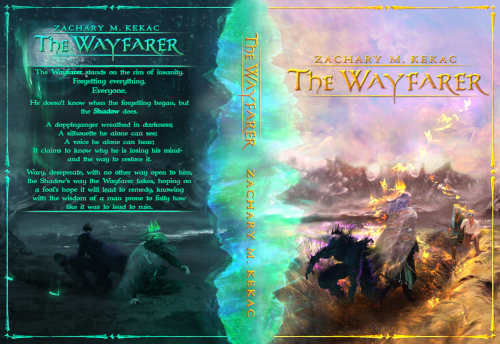

The Wayfarer

The Wayfarer stands on the rim of insanity. Forgetting everything. Everyone.

The Shadow, a doppleganger he alone can see, claims to know the way to remembering.

Wary, desperate, the Wayfarer follows the Shadow, hoping it will lead him to remedy, knowing well how like it was to lead to ruin.

Chapter I: Arkym

• Stirring of Spring •

The Wayfarer stood on the rim of insanity, smirking. His insanity was a thing of forgetting, his smirk a thing of many meanings. It was an arrogant expression, taunting madness to take what mind was left to him; it was grim, a solemn understanding of how little left there was; it was weary, wreathed with the sorrows of a man desperate to remember.

His attention lingered within his mind, the rim on which he stood the threshold of his forgetting. He looked over, down into the descending asylum of hidden self below, where the threads of his memory were hoarded, struggling to peer through the darkness, perceiving nothing.

Above the pit of his forgotten past, in the conscious region of his mind, lingered the few threads of self that remained, each flickering with soft, shifting light, the wistful hue of memory. But they too were fraying, being dragged down into the dark unseen hollows of his unseen self. He was losing himself to himself, knowing that he knew not at all why. That memory was gone too, first of all things forgotten. He knew it was there, at the bottom of the asylum, in the abyss of his mind. He knew too that the only way to retrieve it—the only way to the truth—was the Shadow’s.

Drawing his attention from within, the Wayfarer returned it to the world without. Here he stood not on the rim of insanity, but the rim of the sea. It was night, moon limning the dark with silver. He was perched atop the cliff of a crescent-shaped cove. The waters beneath were calm, the sea feeding the cove through a small channel between the crescent’s tips was not. It hammered into the half-moon wall of black stone, waves so immense they shook the bones of the land as they struck, making it seem as if the world itself tilted with them.

The Wayfarer focused on a black mass at the center of the cove. A small isle of stone.

There on that isle stood an asylum, not of his mind, but of the waking world. Not a place for common folk, afflicted with common ailments of the psyche. There were fairer places for them: kinder, more understanding. No. It was a place for rare folk whose nature it was to unravel the world around them. A place where they could unravel nothing but themselves. It was an asylum not for the sanctuary of those within, but to spare the world without.

Arkym.

The Shadow spoke, naming the asylum. The Wayfarer turned to face it as it stood beside him, a wraith wearing his likeness, a doppelganger wreathed in darkness. He called it the Shadow because to give it any other name, any true name, would be to give it a sense of reality that might well unravel the reality of him. It was a silhouette he alone could see, a voice he alone could hear—his own silhouette, his own voice, lilting and wayworn.

It wears me well.

It turned to him, knowing his mind.

Do not linger.

The Wayfarer knew the Shadow’s mind as well. Inasmuch as one can know a thing born from one’s own madness. Inasmuch as one knows anything of themselves at all. The wraith was a thread of himself. He knew this, though he knew not how. He imagined it was a part of his inner mind hallucinated into existence. A sickness of the psyche. Rare, but not unheard of. He had no proof, nothing to substantiate his belief but the feeling in his bones. It was a part of him. Perhaps the part seeking self-preservation, guiding him to salvation. Perhaps the part desiring to deceive the self, to devour it, for no reason other than having the ability to do so.

Needless consideration. The Wayfarer would go the Shadow’s way no matter what it was or what it wanted. It had led him this far. It would lead him further. To the truth—to the end. Or so it claimed. He did not trust it. He had no choice; no time to wager with, no other option to hedge against. If he hesitated, he would lose the last of himself. He would wander witless in a world which would forget him as effortlessly as he was forgetting it. So, with no other way open to him, the Shadow’s way he went.

The way led here, to the cliff overlooking an asylum for madmen unfit for the world. The message was clear: his madness was linked to one once imprisoned on the isle. A man he himself had put there. A man he once named friend, dearest of all. A friend he’d betrayed to preserve everything else: his family, his world.

A thought slid into his awareness. He looked to the sea, the sky, the asylum, realizing he had no memory of arriving. It was unsettling, but unsurprising. That was the way of forgetting. On the wind of the first thought came another. Did I say farewell?

His eyes grew distant as his inner eye wandered within his mind, searching for his wife, his son, a parting embrace as he began his journey. That memory wasn’t there. In place of it he felt something in him stirring, rising up, rising out. He looked up, wild-eyed, to find the Shadow staring, seeing everything that was surfacing the same as he was.

It was another memory, forgotten, returning. It consumed his awareness. He felt the Shadow step into it, a crooked warden swaggering into the asylum, swinging a skeleton key. A thing of his madness, his madness a thing of forgetting, the Shadow was, paradoxically, a thing of remembering too.

The Wayfarer watched in his mind’s eye as a memory returned to him, the Shadow narrating as it unfurled.

Her voice came over the garden hedge, singing in the spring winds, a song she sang of memory, of love, of you:

…Fair few still walk the ways of old,

Those trails tread by foolhardy souls,

Who wandered where none had before,

Through grove, and moor, and silver shore.

For in those elder days they say,

To wander was the only way,

In lands untouched, in lands unknown,

In wood, and vale, and hall of stone.

Their journey roved and wrought a word,

For leaf, for moon, for bone, for wyrm,

Each name a thread in stories told,

Each tale, each myth, worn ancient old.

Of dragons dark and brooding lone,

Of forest eaves ‘neath dusken gloam,

Of havens hewn from argent white,

Of realms beyond the seams of light.

All memory scrawled upon a page,

All fable passed from Age to Age,

From ash to ash and shade to shade,

A shade of dreamer’s distant days,

For even ash of Ages gone,

May grow a wood, a world, a home.

Where tale and myth may find yet still,

A youthful and foolhardy will.

To follow those wayfaring ways,

To know now and forever say;

Far into dusk their trail does go,

Far into dusk their trail does go…

Her song ended. She spoke. “Do you understand what that means? ‘Even ash of Ages gone, may grow a wood, a world, a home?’”

“I think so.” His tone said he didn’t, despite his words; words of a child trying to appear wiser than he was, ashamed of his own ignorance.

You could hear the smile on her lips and the twinkle in her eyes. “Well, in case any of our rabbit or raven friends in the garden don’t, I’ll say anyway.”

He was too old to believe that foolishness, too young to own up to his own. So he let her speak, and in listening he learned. “Even from ash—the stuff of nothingness—can come the stuff of somethingness, with a little time. It’s the way of the world, Tärin. Of ours, of others.”

He lit up. “Other worlds Da’ has been to, too?”

You smiled, answering, “Others Da’ has been to, too.”

“Aëros!” They both turned, eyes alight. Her voice held the slightest rasp, a subtle sultriness under all the spring sweetness, a wit and wryness sewn into the seams of world-weariness she worked hard to hide. But you saw those seams, saw all of them, all of her, and loved her for everything you saw. She was your person; you were hers. Your Aūriel, her Aëros. She saw your shadow in her periphery and turned, giving you her eyes, her smile, her vulnerable, enduring love.

She leapt into your arms. You breathed her in—lemongrass, lavender, mint leaves. You smelled like…well, like you’d been on an adventure: like old smoke drifting from dying embers, like worn muscles and weathered skin, like heavy rain had been your only shower. She didn’t mind. It was a familiar scent. It was you.

“Da’!” Tärin. His shifting-silver mane reflected father and mother both, his face hers, his eyes yours—solemn, curious, keen.

“Aha! Aūriel, Tärin! How I’ve missed you!”

“We’ve missed you too, my love.” Her words whispered in your ear, your soul, filling you with sorrow and joy. Love, a thing of duality.

Tärin took off running as he remembered something he was proud of. Then he remembered he had to tell you what it was first. “Da’! The range!” He frowned, focusing. “My arrows!” He stumbled, frowned deeper, focused harder, too roused for the measured thought of the man that was waking within him. His mind still ran away from his words as swiftly as most men run from both. “I have to show you something!” Near enough.

He wore a bow over his shoulder—yours. The earliest of your own artifice, not well made, but well-worn. You doubted if a day had passed where it hadn’t seen the range. He was so proud of it, for it was an artifact of his father, a thing all sons long for, indifferent or ignorant to its imperfections. Sons do not see such things until they are fathers themselves. Such is the slow way of wisdom.

“Tomorrow, son, I promise. It’s dusk, and I have to speak with your mother.”

He stamped, pouted, rolled his eyes. Youth.

You waved him along, laughing. “Run on!”

He huffed, and relented. His will was hardening, but yours was stronger still and he bent beneath it, defying it only with words. “You’re just making excuses because you’ll fall asleep after you finish, old man!”

“Tärin!” Aūriel did her best to bite back her own laughter, red embarrassment rising into her cheeks and the long tips of her ears, which peeked through slits in the brimless knit cap she hardly ever went without wearing.

“I’m going, I’m going!” He darted off, ducking under vines and leaping over hedgerows as he went. He ascended a trellis, dove from its crest, was gone. Your son, threaded through.

“Your wit is showing in him, Aëros.” She sighed, wistful. Her eyes held all the shifting hues of an aurora, flickering and iridescent, twisted with threads of teal and turquoise and bright, burnished gold.

Your smile met your eyes—silver moons, full then, long ago, now fading crescents, hollowing away. “You say that as if my wit isn’t the reason you married me.”

She stole your smile for herself, wore it with familiarity. “I married you because you don’t fall asleep after you finish.”

“Is that right?” You wrapped yourself around her, pulling her close, eye to eye, delicate. Then you tugged her knit cap down over her face, flustering her. “You’ll be on your way to disappointment swiftly then.”

You scooped her up, walking to the stairs, toward the bedroom. She giggled, squirmed, and relented, nestling into your arms. She lifted the brim of her hat back into place and looked up out of one aurora-hued eye, wondering. “What’d you need to tell me?”

You kicked open the door, tossed her onto the bed, leapt after. “It can wait.”

She laughed as you tussled, the wistfulness in her eyes finding its way into the crooks of her mouth, the whisper of her words. “I would be happy if I died today, my Aëros.” It was her promise, the oldest of them. A promise that would seem strange to most. A promise that endeared her evermore to you.

“As would I, my Aūriel.”

You fell into one another—you, wearing the smile you wore when first you met; her, the smile you would see her wearing at her death.

Aëros blinked, returning to the waking world. The Shadow returned too, standing before him, eyes meeting his. Silence. He spoke, hesitant. “Was that now? Was that just now?” He shook his head, knowing. “No. That was… long ago. But…” What he’d seen was memory, mostly...

The smile you would see her wearing at her death.

It was nonsense. It was nightmare. Yet there, nested within it, was a wretched feeling of familiarity. His eyes fell to the ring on his left hand, joining his soul to his Aūriel’s. It was the key to his promise, to his journey; the key to many things. It was of worked Argynt, the silver metal weaving about his finger like the roots of an underwood, a narrow band of wyrmstone worked throughout it, hoarding the moon’s silver light like a dragon its trove, refusing to reflect it. It was inscribed with her wisdom, written in the language of the First of the First, taught to her by him, her husband, the Wayfarer—last of the Last of the First: Always forward. Always on.

He often found himself muttering the mantra in his mind, as if afraid that silence would steal its memory away. Foolish. So long as he had the ring, he’d keep his promise to return to his family. As a man, not the shadow of one. He wondered to himself again if he’d said farewell. His home wasn’t far. A few days’ trek. I have time.

No.

Aëros measured the Shadow, the wretched feeling of familiarity now warring with a feeling of wrath towards the wraith and its obfuscation. He ground his teeth, growled. Madness brought the Shadow, and the Shadow brought memories. That would seem a boon to one who was forgetting—it was not. Regardless, he knew the Shadow was right. He’d said his farewells. I won’t feed my madness. I won’t submit to hysteria.

The sea rolled into the cove, and the Wayfarer watched the waters tilt, heave, hammer into the half-moon as if their only desire was to sweep over the cliffs and drown the thing they were protecting. Arkym. A place of protection itself. Aëros knew that even drowned, the memories of that island, of his friend’s internment on it at his behest, would remain vivid. They would linger, and in the end, were likely to be the last thing he would forget. The mind had a way of holding onto its grief.

Arkym marked the beginning of his betrayal. Dún—a crypt in the midst of the necropolis named the Barrows, where the bones of his friend were buried in a sepulcher of carven crystal—was the end, far off, far away.

The Shadow spoke, shearing the silence.

Move on.

The Wayfarer considered the beginning, and the end. His journey would take him from here to there, from Arkym to Dún, just as his betrayal had. For it was there, in the grave of the man he named friend, the man bound up in the meaning of his madness, that the memory of how and why rested. It was, of course, buried in his mind too. But it could not be retrieved without first standing where it was formed—or so the Shadow said.

It made sense; in returning to the place of the first thing forgotten he would return to the rest. He could only hope a fool’s hope until his journey’s end, and it was far yet, his way long and winding, with much betwixt and between here and there.

Here the Wayfarer stood on the cliffs of Crescent Cove, the Verdant Fells stretching out behind him—the western grasslands of hills and valleys, peaceful, serene, unfurling their vastness far beyond sight. A star was falling within the night, drifting from the forever-shattered moon, radiating pale, silver light. It wisped over the Fells and vanished, finding rest in the darkness beyond the southwestern horizon, in the direction of his destination, in the direction of Dún. He turned from the sea, the asylum, the beginning, setting foot and mind toward the end.

The Shadow strode ahead of him, its silhouette stalking through the dark, darker still. Grass rolled underfoot, gentle on his soles, bare as they always and ever were, weathered to roughness from a lifetime of adventure. Spring rain stirred in the eve, thin and scattered. He drew up the hood of his Shräud—a cloak drawing night down around him, the material threads of its fabric woven with the immaterial threads of Dräu, making him difficult to discern. Not invisible, but as a shifting, shapeless shadow on the edge of perception, easily missed. It was of his Aūriel’s artifice. He found her scent on it even now: lemongrass, lavender, mint leaves.

Though night encircled him, he drew a crystal-framed lantern from Nowhere and illuminated it, limning his silhouette in silver and hiding him from the dark. Lúmoths drew around the artifact, fluttering, adding their natural light to its own.

The Wayfarer walked, went on, was silent. Silent so as not to disrupt the night-song of the Fells. Silent to search for answers in the miasma of his mind. Silent to mark the stride of the figure that was stalking him; there was more in this world to worry over than madness.

Haze thickened overhead, veiling moon and stars and darkening the Verdant Fells until they were half-hidden. The Wayfarer dismissed the betraying radiance of his lantern, the lúmoths dispersing as its light faded and the dark swallowed him.