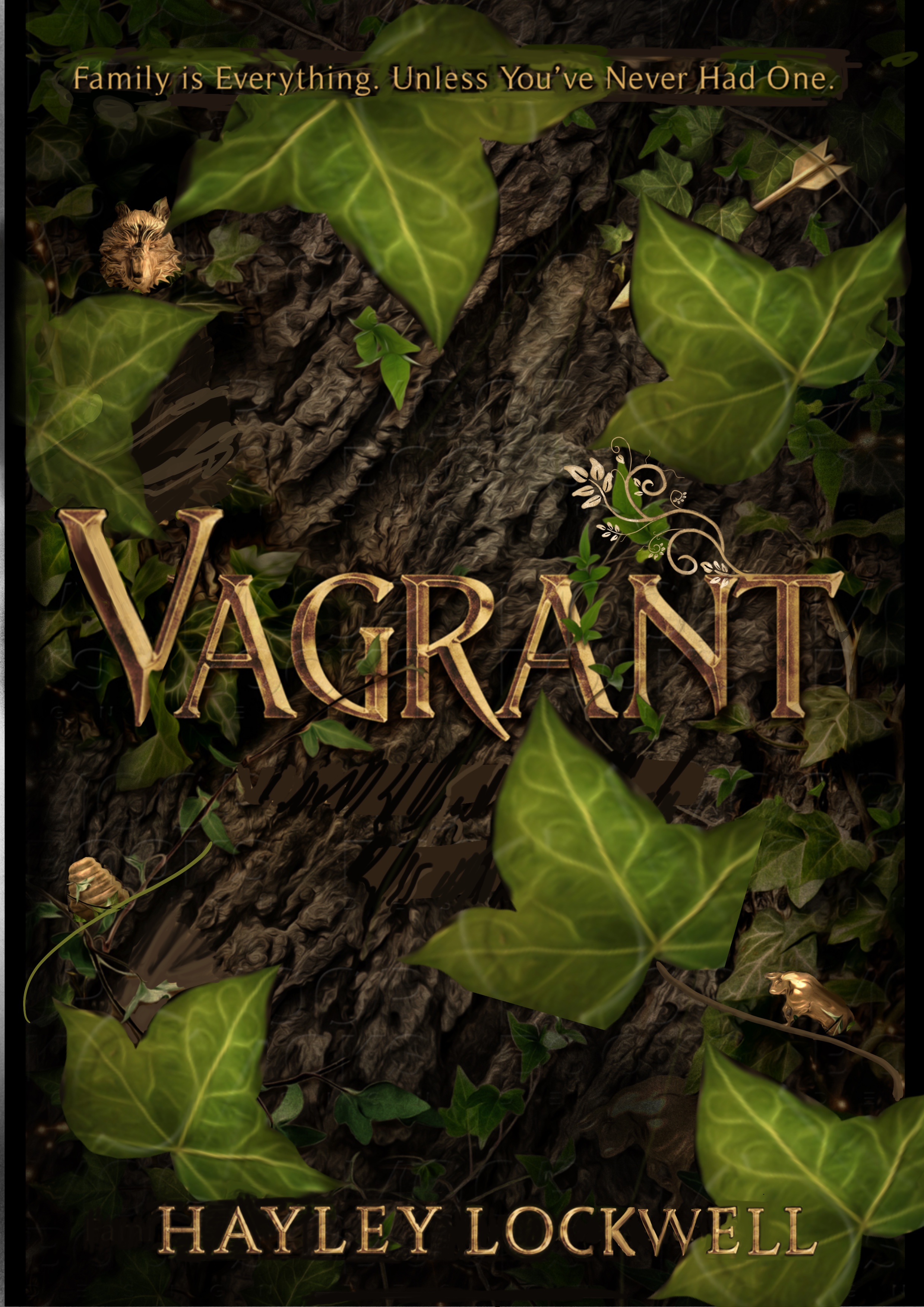

Vagrant

I had never been considered a heroine, and today confirmed it.

I doubled over clutching my hand, knife and half-skinned rabbit tumbling to the ground. I shook my fingers with a grimace, sending a trail of red droplets hissing into the fire.

That rabbit was a stroke of luck I hadn’t expected: a flash in the woodland, and my arrow was fitted – and fired – before my heart finished its beat.

I allowed myself two breaths with my eyes shut before I brought my hand up to look.

My palm gaped open. Whether it was down to my blunt knife – in desperate need of sharpening – or fingers too frozen to work properly, it was a costly mistake.

I hesitated, wondering what to do, blood dripping from my fingers. I looked down into the valley at the circle of huts. I bit my lip. I tucked the rabbit inside the door of the hut and set off reluctantly towards the tribe’s camp, the icy morning air biting my cheeks, my breath coming in puffs of cloud. Out of habit, I scanned the horizon, then caught myself and shook my head.

Not yet.

I trudged down the hill, blood dripping steadily onto the ground leaving red dimples in the snow. The worn soles of my leather boots slipped on the ice as I walked down to the meadows past the river, which snaked along the landscape like a massive grey serpent writhing through what would become lush, green pastures in spring. For now, the skeletons of trees stretched out on silver grass, rigid with ice, as far as my eyes could see.

Somewhere in that direction was the next tribe’s camp, our closest neighbours. Not that I’d been. There was too much to do here. I couldn’t get it all done as it was.

I reached the outskirts of the village and picked my way through the round stone huts of the camp, their roofs low to the ground to save on stone, like a giant ring of stocky grey mushrooms.

The tribe leader, the warriors, the families of importance, all held the coveted inner-circle status. Then came the craftsmen, the blacksmith, the farmers. On the outskirts of the ring were the ones just getting by, the ones clinging to the tribe for protection.

Our tiny, solitary hut was a very long way away.

I kept my head down as I passed women and daughters sitting in their doorways chopping roots and meat for supper. I ignored the whispers, the sly looks. I had heard it all before.

I stopped outside a squat hut with cooking smells wafting from the doorway. ‘Craven?’ I didn’t like him but I wasn’t sure what else I could do.

The chink of cutlery. A long-suffering sigh. ‘Enter.’

I ducked under the doorway and stood awkwardly in his round hut.

Our camp healer was an old man with fat, sweaty fingers and breath that smelt of old beef. He sat at one end of a large person-sized oak table, half-eaten dinner and a tankard of ale in front of him. At the other end of the table, his surgical tools, saws and knives were laid out – some clean, some not.

‘Yes, er …?’

I cleared my throat. ‘It’s Gelda.’

‘Right.’ He watched the blood drip onto the dirt floor as he mopped up gravy with a hunk of bread. ‘You’re bleeding on my rug.’

I stepped hastily off. ‘I’m sorry to interrupt your supper, but I slipped with my knife.’ I held out my hand.

Craven heaved himself out of his chair, navigated his way around the table and bent over my palm. Or at least as much as he could before his rotund belly hampered his investigation. My skin crawled at his touch. ‘Looks nasty.’

I gazed at him anxiously, waiting.

He straightened up. ‘It’ll need stitching. What do you have?’

Surely he could see the problem I had? I shook my head, confused.

He rolled his eyes skyward at my incomprehension. ‘Medicine is not cheap, erm …’

‘Gelda.’

‘Gelda, and as much I desire to offer my services without charge – out of the goodness of my heart – there is no such thing as a free lunch, as it were.’ His gaze wandered back to his supper, now rapidly cooling.

‘Oh! To trade? Well, I have …’

My precious catch. But meals were pointless if I couldn’t use my hand for weeks.

‘A rabbit?’ I offered. ‘Meat and the fur? It’s already gutted. I’ll even skin it for you if you like?’

‘Someone’s already given me a bear skin for the amputation I did yesterday.’ He sighed, clasping his hands around his belly. ‘Nasty business. That poor, unfortunate warrior.’

I grimaced. I had heard the screams all the way from my hut.

He shrugged. ‘Ah well, lose the leg and save the warrior … not that he’ll be much use as a warrior now. Marauders didn’t used to be so brazen. You need to take care, up on that hill, all by yourself.’

I stared at him. ‘I’m not by myself. He’ll be back any day now.’

He leaned closer. ‘Don’t you get lonely?’

‘No.’ I racked my brains for what I could trade. ‘What else would you take? Potatoes?’

He shook his head, his jowls wobbling beneath. ‘I already have plenty.’ He leaned closer, his gaze travelling slowly down my body. ‘But, you see, I get lonely too, so you might have something else I’d be interested in.’

I looked up from trying to hold the fleshy edges of the wound together, wondering what on earth I had to offer.

His smile creased into an extra jowl.

My mouth dropped open. He wasn’t serious—

I walked out of the hut a heartbeat later, trailing droplets of blood behind me, not caring if I got some on his precious rug. Dirty, dirty old man.

On my way back, I debated trying to stitch it up myself, but when I imagined piercing flesh with our old darning needle and string, I wasn’t sure I could do it.

I squatted down by the river and washed the wound clean in the frigid water, and wrapped my hand in an old rag from my pocket hoping that it wouldn’t get infected. My stomach growled as I used my uninjured hand as a cup, lips numb from the bite of the ice. If blood fever set in like that warrior’s leg, the price for a decent amputation would be high, and there was no way I could afford it. If it came to that, I would have to chop it off myself, which I doubted I’d be able to do. Either cowardice or infection would kill me, which seemed a fitting end to the tribe’s outcast.

I called out a greeting as I passed old Alma’s hut. She, too, lived out on the outskirts of the tribe between us and the village. She sat in the doorway of her hut spinning, creamy wool in giant balls around her, fingers gnarled with too many winters. Few of the tribe acknowledged her – only when they needed a new winter shawl or blanket, of course. She couldn’t see me, eyes milky from age, completely blind, but she nodded, fingers never stopping from their work. I would take her some of the rabbit once I had cooked it tonight; she had no family to look after her.

I glanced over my shoulder, hoping to see him through the trees but instead, a flash of rust caught my eye as a squirrel dug frantically in the earth at the roots of an ancient oak. He caught sight of me and scampered up the trunk, sitting on a bough to chatter obscenities, shaking his bedraggled tail like a fist.

My lips twitched. ‘I’ve been called worse, you know.’

His tufted ears twitched angrily.

I bent down and scooped out the beechnut lodged in the frozen ground and placed the nut onto one of the lower branches. ‘Here. A present – from one frozen creature to another.’

I turned as I reached the brow of the hill to see a tiny furry body hurtling back up the tree, nut safe. I sighed. ‘May we both survive this never-ending winter.’

The rabbit was gone when I got back to the hut.

I bit my lip; I felt an ache in the pit of my stomach as I stacked more wood on the fire and huddled down next to it, not caring about the smoke in my face. I pulled yet another woollen layer on, fingers catching in the holes in the sleeves as I dragged it over my head, then brought my hands up to my mouth, ignoring the ash covering them, and blew into my fists. My fingers were speckled with tingling red lumps.

It didn’t matter how little you had; there was always somebody who wanted it.

***

My axe jammed again.

I flexed my clumsily bandaged hand, rubbing my fingers against my trousers, and stood up, braced my foot against the log and levered the rusty axe head out. I could barely straighten up this morning; my bones had seized overnight. My breath hung in frozen clouds around me as I worked but at least the movement was keeping me warm. I would be fine as long as I kept moving.

My stomach growled as I swung my axe. I had survived sixteen winters, but I had only just made it through this last one. With no fat under the flesh, my skin appeared almost translucent against the sparkling snow, the backs of my hands nothing but skin pulled taut over sinew like a toad’s webbed foot and blue blood vessels running like icy branches up my arms. Each summer, I tried to add a layer of reserves over my ribs, and each winter the fat leached from my body a little more.

I gave the trunk an almighty smack, trapping my fingers in the splitting handle of the axe, and the blunt head stuck again. I gritted my teeth and placed one foot on the bark; the other was sunk up to my ankle in the mire. I heaved, wrestling with the axe. It released just as Demara walked by, arm in arm with her bosom friends, the twins.

My foot slipped and I flew back, losing my footing, axe head burying itself in the mud less than a handspan from her fur-lined boots and spattering dirt up her trousers.

Ailis and Aine shrieked, eyes bulging in horror.

Demara’s brows snapped together as she stared from the blade by her foot to me. ‘Watch out, idiot!’

The twins nodded in agreement. Their family herded goats, and I often secretly thought the twins looked like goats, complete with protruding ears and buck teeth.

Despite the cold, my face went hot as I gazed up at them from the ground. ‘Demara, I’m so sorry …’ Cold mud was soaking through to my underwear and I scrambled to my feet, grasping what was now just a wooden handle.

Demara glared at me. ‘You could’ve chopped my leg off! What do you think you’re playing at?’

Demara was about my age, maybe a couple of winters more, but she couldn’t have been more unlike me. She was the most beautiful girl anyone had ever seen. Everyone said it.

And Demara agreed.

Strong tanned arms; huge brown eyes; and never a strand of glossy dark hair out of place. She never made mistakes and she probably never bit her perfect oval nails – she could have any warrior she wanted with a snap of those immaculate fingers.

My eyes were the colour of water. Not the deep blue of lakes on sunny days, blue skies bouncing off the surface, but the colour of the pond outside camp mid-winter, where nothing would grow except grey algae. My scruffy straw-coloured hair looked like someone had dumped an untidy haystack on my head. And it refused to grow past my shoulders, probably because I was always hungry.

I retrieved the head of my axe from where it had buried itself in the sludge, painfully aware I looked ridiculous with my hair plastered over my face and mud splashed liberally up my tunic.

‘My father will be furious when he hears you nearly crippled me!’

I winced. There were twelve Northern Tribes, and her father was the tribe leader of this one – although considering his self-importance, you would think he ran all twelve.

‘I really am sorry,’ I said, my teeth chattering as the cold soaked through my trousers.

She huffed. ‘I can’t believe you manage here all by yourself.’

‘I manage just fine.’

Her lip curled. ‘You’ve got trust issues.’

‘Believe me, trust issues are the least of my problems.’

‘Did you just talk back to me?’ Demara drew herself up straighter, her shoulders rigid. ‘Do you have something to say, Gelda?’ she said sweetly.

I bit my lip to stop myself from saying anything I might regret. It would only come back to bite me. I shook my head, wiping the muddy blade on the one remaining clean patch on the front of my trousers.

‘My father will hear about this.’

‘I’m very sorry, Demara.’

She looked over me, taunting. ‘Has he finally had enough of you?’

The twins snickered through their buck teeth.

I avoided her gaze. ‘No.’

‘How many moons is it? It must be at least six, surely?’

I swallowed. She laughed, a light tinkling sound the twins were quick to join in with, then turned on her heel and gestured for the twins to follow her. I flicked clods of earth off my clothes. I could still hear their voices as they made their way back to camp.

‘Do you think she cuts her hair with that axe too?’

‘Cuts it? It looks like one of the asses chews it!’

Their shrieks of laughter floated back to me.

My chest tightened as I examined my axe. Tonight I would re-attach the head to the handle. It desperately needed sharpening; soon, it would be quicker to gnaw through the wood with my teeth.

***

It was past sundown by the time I eventually heaved the last few branches up the hill to the hut, arms aching, injured hand throbbing. I massaged my neck, wishing I had Araf to help me haul the wood. But, of course, he was with Merrick.

I lit a fire. It was the only time I stopped, kneeling next to the flames while I cooked supper, holding my fingers out to the warmth, the knuckles protruding on the backs of my hands. I squinted at the cloudy horizon, scanning the south as the sun disappeared somewhere beyond the mountains.

Where was he? When he was here, we sat by the fire in silence while we ate supper, but at least there was someone to sit with.

***

I tugged the heavy plough blade to Jatarn’s hut, my newly sharpened axe over my shoulder.

Demara sat outside on a wooden bench, chopping vegetables at an oak table. She lifted her eyebrows as I approached, a sly smile playing on her lips. ‘Still muddy?’

I ignored her. ‘Where does your father want this?’

‘Put it around the back.’

I heaved it along behind me.

She was the daughter of the tribe leader and that gave her identity and status. She knew exactly her place in this world. Who was I? Who should I have been? Without parents, I had no heritage.

No identity.

She didn’t know how lucky she was.

As I leaned the blade against the stone wall, a heavy hand landed on the back of my neck. I jumped and the axe slipped out of my grip as I turned, raising my arm to protect my face.

The warrior in front of me leaned an elbow casually against my throat. ‘Where is it?’

‘Hello, Madog.’ I tried to keep my voice calm.

Three winters older than me, Madog was a tribe warrior and was supposed to protect the camp. In reality, he spent much of his time swaggering around after the camp women, half drunk.

‘You said I’d have the next one.’ His face was in mine. ‘So where is it?’

The stone digging into my back prevented me from retreating any further. ‘Geese are scarce this time of year – I just need a bit more time—’

‘Spare me the drivel.’ He shook me.

‘I’ve shot nothing – they’re not back yet!’ The words jerked from me.

‘How do I know you haven’t already eaten it?’

‘I … I don’t know. But I’ve eaten nothing but roots and nettles in weeks, I swear.’

‘I can beat you black and blue right now and no one will raise an eyebrow. No one cares what happens to the tribe outcast. You think Craven’ll bother patching you up after I’m done with you?’

I swallowed, heart hammering. ‘Merrick wouldn’t let …’

‘But Merrick isn’t here, is he?’

‘Please, just give me seven days and I swear I’ll …’

His grip tightened. ‘One.’

‘Two?’ I said, breathing fast. ‘Please?’

He raised his fist and I cowered away. ‘Alright! I’ll get it.’

‘Tomorrow,’ he snarled, his teeth a handspan from my cheek, ‘or else.’

‘I’ll get it!’ I said, arms covering my face. ‘I’ll get it.’

My knees buckled under me as he let go.

He bent and picked up my axe. ‘I’d make sure you do. Better be careful, Gelda,’ he said, running his finger over the newly sharpened blade. ‘Wouldn’t want anything to happen to that ugly face of yours – you wouldn’t be able to afford the bandages.’

He slung the axe over his shoulder with a wink, and strutted away. I leaned against the wall, my legs shaking, until my heart returned to normal.

What would I do if there weren’t any geese by tomorrow?

Merrick would be back any day now. He had to be.