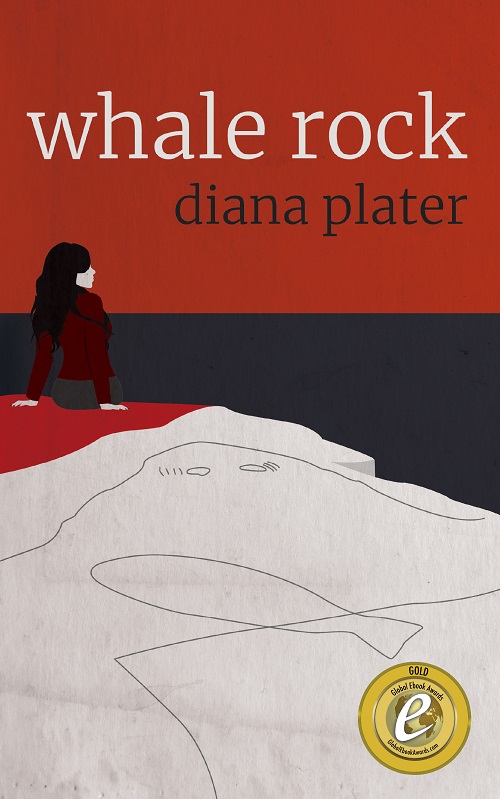

Whale Rock

Chapter One

“If Tom had died they would have brought me casseroles,” Shannon said to herself, knowing full well her lips were moving. “But when you split up with your husband the neighbours don’t give a damn.”

She was standing at the coffee machine, which sat on a huge wooden bar, a slab of polished timber that felt connected to the earth. But she didn’t feel connected anymore. Not to the ground. Not to most people. And certainly not to her customers. None of them cared about her personal situation – they were more interested in their next social gathering or whether the surf was up. Her life wasn’t going to affect their choice of a latte over a flat white on an April autumn’s day at Shannon’s Café perched on top of a hill between the beaches of Tamarama and Bondi.

Well, she didn’t care what people thought. It was her café, and she’d talk to herself if she wanted to. The yummy mummies and their designer-dressed babies, scary real estate agents and bronzed surfies could all go about their exciting lives partying, working and swimming in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. So long as they paid for their cappuccinos and carrot cakes, they could do what they liked.

“You still have the café,” that’s all Tom had said as she’d agreed to move to their upstairs flat after the tenants left. He’d stay on at their Paddington terrace. Shannon’s was not a particularly imaginative name but that’s what she’d christened the café when she started running it two years before. Her five minutes of fame. It was tiny; there was just enough room for four tables inside and two long benches and a table out on the street but it was big enough for her. It used to be a groovy little place, wedged next to a post office, where wannabe Hollywood stars photocopied their latest scripts and sent their resumes to agents. But sadness had descended on it. And the customers seemed to feel it.

She brushed her long dark-brown hair out of her eyes as she packed the coffee. Her style hadn’t changed in the two decades since she was a teenager. She cut her fringe herself in the hope she could put off the inevitable trip to the hairdresser. She didn’t want to be talked into dyes and foils and perms and curls, but the other day she’d found her first grey hair. The clock was ticking. Whatever happened, she’d never change her uniform of jeans, sloppy jumper, a scarf on cool days and walking boots.

Tom had suggested she tame those waves. “Do something with your hair, Shannon. Other women look after themselves, why can’t you? And wear something feminine for a change.”

She’d wake up next to him, her eyes red from night-time crying. He was way over the other side of the bed, deathly quiet.

Stop nightmare dreaming. Better to check out the latest less-than-enthusiastic assistant, Nick. How did he wear his apron so casually chic, overlapped and tied at the front? But that’s where the sexiness ended. His white T-shirt revealed more rib than muscle and his skin was pale. His longish black hair curved into his tattooed neck, and a wispy beard didn’t quite cover his chin. He came to her in need of a dollar, saying he was an experienced barista but his froth came out like runny yoghurt. And when he tried to do designs with the chocolate on top it turned into a mushy mess. But she told him he could keep the tips if he learnt quickly.

“Here you take over, Señor Barista,” she said. At least the young female customers liked him, with mutual flirting and winking at times brightening up the sombre atmosphere.

She pulled her powder-blue woollen scarf up around her neck; the café felt the ocean winds. The colour of the sea that she could smell in the air. Fringed by 1930s red-brick flats and yellow bungalows, the road the café was on led down to parks and a coastal walk past ancient Aboriginal engravings, which overlooked the ocean. The parks were filled by six am with skinny women who were addicted to exercise. They ran up and down the volley ball field, did weights and boxed with each other or their personal trainers, who barked orders at them. She used to like men like them. Look at Tom. He was heavily into exercise.

Many of these trainers were her customers; they ordered fresh juices in front of their clients but she’d spotted them chilling out after hours drinking beer at the nearby pub with their tradie mates.

She now preferred her arty clients – filmmakers and actors, who had given her signed photos of themselves, which lined the wall above the counter. On the other walls were black and white framed photos of old Paris and Frida Kahlo prints that Tom had ribbed her about when she bought them at the Art Gallery shop. So what if they weren’t avant-garde?

Today a bunch of exercising mothers were sitting outside the café, their strollers and prams taking up every bit of footpath space. When her five-year-old son, Maxie, was born Shannon had inherited her sister’s old-fashioned pram, which converted into a stroller with one flick of the wrist. Tom had turned his nose up at it; he wanted her to use a super-duper child-mover. She resisted; that old one was so much easier. But these mums had the latest inventions, worth more than her second-hand Toyota.

They ordered babycinos, talking to their toddlers in sweet, high baby voices as they screeched like seagulls at Shannon for their caffeine and chocolate hits. Their voices rose even higher as their spoke to each other and into their mobile phones, so the whole world could hear every word. They were like paddle pop sticks, tanned even in winter with gorgeous hair in every different colour. She couldn’t imagine having to look that perfect all the time.

One of them grabbed Shannon’s arm as she collected their cups. “Shannon, isn’t that girl inside with the blonde pony-tail famous?” she asked.

“A legend in her own lunchtime?” her particularly thin friend commented as they laughed in unison.

“She’s an award-winning actor actually, Jane,” Shannon answered. She knew Jane from Maxie’s school, the local public one. Her older daughter, Clarissa, was in his class. Jane was always the centre of a scrum of mums at the gate at drop-off and pick-up time. They would spend an hour making sure their little darlings were settled in at school, or at least using that as their excuse to have a good old gossip. And then they’d go off to exercise.

At school assemblies Jane’s set would clap like mad for their own children but ignore others like Maxie, whose mothers weren’t one of the clan. And when Shannon picked him up from school she felt as if she needed to be wearing riot gear to run the gauntlet.

She was forever late, and the ones at the gate tut-tutted as she raced past them, finding Maxie alone in the playground. Or she’d be the last one to collect him from after-care. She did have a business after all and what the hell did they do?

“So, Shannon, how is your handsome husband?” Jane asked. “When are we going to see him at canteen duty again?”

“Don’t you see him when he picks up Maxie from after-care?” She didn’t want to explain her separation although she guessed Jane knew all about it. She didn’t want to explain anything to her.

“Oh no, we don’t send our girls to after-care,” her friend, who wore her hair pulled back in a hairband, said. Shannon hadn’t come across her before. Her daughter must be in another class.

“I did see Tom’s mother at school the other day,” Jane went on. “Aren’t you lucky that she’s helping out with babysitting while you run the café?”

Irina? Shannon hadn’t heard that her mother-in-law was now on pick-up duty. Tom had insisted lately that he have Max stay over more often and the two days a week had stretched to six and even seven sometimes.

“Better for you to concentrate on one thing at a time,” he’d said to her.

But didn’t he know women were geniuses at multi-tasking? Shannon turned up the iPod music – a Radiohead album that Nick had chosen – to blot out the mums’ conversations. Now they were discussing what high school their daughters would go to but even the loud music didn’t work.

“Saint Joan’s, I’ve already got Clarissa enrolled,” Jane, who had pulled up her skin-tight top in order to breastfeed her baby, said. “But I’ll get her to do the selective schools’ test just in case.”

“Oh you wouldn’t want her to go to a selective school would you?” her friend asked. “Do you really want her to do all that coaching?”

“She’ll be fine without coaching. I’m so blessed to have an intelligent child. The others wouldn’t get in without it though.”

Didn’t seem too bright to me, Shannon thought. Maxie, in his innocent way, had told her about the dumb questions Clarissa asked in class so she doubted she would get into a selective school with or without coaching. Of course, her Maxie would sail in! Well, she hoped he would.

“Taking places from local children, it’s just not fair,” Jane continued. “Stop it Clementine.” She pushed her toddler away, who had jammed her whole hand in her babycino and was now trying to feed the baby.

Shannon thought the really unfair part was being stuck with a mother like Jane, especially somebody who would call her poor child Clementine. Why did people with nice, simple names come up with such pretentious ones for their children? It wasn’t as if they’d grown up playing banjos in Louisiana. It was time a one-name policy was brought in here; if the Chinese could introduce a one-child policy why couldn’t the Aussies insist on only one name for children – Janet or John perhaps? Or Max, now that was a nice, simple name. But not one Tom had liked that much.

Oh no, she was thinking about Tom again. It had been eight months since, standing at the Paddington front gate, he’d announced he couldn’t live with her anymore. It wasn’t a surprise. He’d hide away in his office when he came home from work and go to bed after she finally fell asleep. She guessed he couldn’t cope with her melancholy.

“Can’t you see how much you’re hurting me?” she’d said to him.

But he didn’t even say sorry.

I am floating above my bed, my mind has left my body. But my soul lingers on. Am I dead?

I can see midwives and the doctor hovering around. Tom is standing next to my body, holding my hand, his usually tanned face now pale.

“We’ve still got Maxie,” he keeps saying, over and over and over again. We still have our beautiful little boy.

The mothers were leaving but Jane wasn’t in a hurry. “I feel like another coffee,” she said to her friend, who reluctantly waited for her, muttering something about being late for book club.

Jane put the baby back in the pram and went inside to order another soy latte and babycino for Clementine.

Shannon was standing next to Nick. “Maybe her breast milk’s soy too,” she whispered after Jane sashayed back to her table.

He rolled his eyes.

She thought of how Maxie loved his treat when he came to the café, referring to it as “my cupofcino”. Was he alone in the playground now munching on his apple, she wondered as she went to the iPod and turned off the music.

“I was enjoying that,” Nick complained, working the coffee machine.

“There’s a reason why this café’s called Shannon’s,” she said, putting her hands on her hips. “I just want silence.”

“Wish you’d make up your mind.”

“Wish I was down at the valley,” she responded, shaking her head and pursing her lips. At the family farm a couple of hours’ drive south of Sydney, away from all this clutter and chaos, walking up hills or jumping from rock to rock in the creek. She loved the peace of the bush, punctuated only by the mooing of cows and bird calls – the Eastern Whip-bird, with its drawn-out whistles and whip crack, and the female’s “chew chew”. They were a pair, those whip-birds, staying together for nearly a lifetime.

Shannon took the drinks out and noticed Clementine kneeling on the bench, playing with the sugar she had spread all over the table. She tried to edge past the double pram to place the cups away from her. But the toddler turned around at that precise moment and leant back to rock the pram, pushing it into Shannon and forcing her to trip and spill the coffee. Soy froth went everywhere. Maybe it was because of her years of dance classes but Shannon was able to plonk the cups on the table without dropping them. Her face was red. “Get those bloody prams out of the way,” she yelled.

“Don’t swear in front of Clementine.” Jane swung round, her hair moving in sync with her head.

“Mummy, my babycinooooooo,” Clementine yowled, putting her hands in the mix of milk and sugar and licking her fingers. The baby was howling now too.

Shannon passed the half-empty babycino to Clementine, trying to soothe her by touching her arm but Jane snatched her away.

“Keep your hands off my daughter,” she said.

Shannon couldn’t contain herself any longer. “Oh go fuck yourself,” she burst out.

The toddler poked her tongue out at Shannon while Jane bundled her into her pram. “We’re never coming back,” she said.

Pain sears through my body. It comes again in a rush of blood. The midwife puts a mask over my face. Gas. I’m starting to go. Is this what it feels like to die in a hospital ward? Ugly grey walls, chrome bed, all so clinical. Is this where I want to die? No, not here surrounded by nurses and doctors who don’t know me.

I want to leave this wretched place, this Earth, when I’m alone far away from other people, deep in the valley, way up my creek, where all you can hear are lyrebirds and water tumbling over the steep rocks.

Shannon felt a reassuring hand on her shoulder. “The Mums and Bubs Club giving you grief?” a stocky man in khaki overalls asked.

She looked up and he gestured at Jane and Hairband retreating with their jangle of prams, toddlers and babies.

Shannon was relieved it was her regular, Colin. “Did you see it all?”

“Sure did,” Colin nodded. “And heard the swearing too.”

“I wish I had some smokes.”

“Now, now. I thought you were giving up.”

“One day.”

Gliding between the double-parked cars and the phone boxes was another labourer, who grinned at her and she felt herself blushing. She tossed her scarf over her shoulder so it wouldn’t trail in the milky mess as she attempted to clean up.

Colin turned to introduce him. “This is my mate, Rafael. He’s working with me on the building site. This is Shannon, the proud owner of this establishment. I convinced him you had the best coffee in town.”

Shannon wiped her hands on her apron, then shook Rafael’s hand. “Sorry about my swearing. We’re really all just one big, happy family here.”

Rafael smiled. “They need a licence to operate those prams.”

“Yes, a truck licence.” She observed something she couldn’t quite make out in his dark eyes. She turned to Colin. “Cap, sir?”

He nodded. “Of course, my dear.”

She loved Colin and his crinkly face, even if it was looking a bit the worse for wear. He must have been handsome once. He reminded her of the Koori boys she went to school with. They were witty, knowledgeable about nature and never wasted time talking about nothing.

“And for you, Rafael?” She guessed he would have to be at least ten years younger than Colin, who was possibly in his mid-sixties. He had a face that had seen a lot of life but he was still good-looking, dark-skinned with long black hair. She liked the look and smell of men who did physical work for a living. Muscular men with strong arms that it must feel good to be wrapped in. She bet Rafael knew how to chop wood, like those Koori boys.

“Short black please.”

“At least I don’t need cocaine to be manically depressed,” Shannon looked up as Jane’s massive Range Rover passed. She was honking her horn as she tried to steer it around a car parked in front of the café.

“She must have got her truck licence,” Rafael joked.

“Truckies and their uppers!” Colin joined in.

Nick looked amused as he made the coffees and passed them to Shannon. “You’re always friendlier to the male customers, you know,” he said.

“I am not.” But she was glad she’d put on her blue scarf that morning. Shannon knew that colour suited her.

She took the men’s order over to their inside table, where they’d divided their newspaper in half. Colin was checking out the dogs at Wentworth Park and Rafael had the foreign news.

“So, Salsa Queen, you’ve recovered?” Colin put down his paper.

She nodded. “But I’ve lost my rhythm, man.”

“It’ll come back, Shannon.” Colin looked fatherly.

“You can dance the salsa?” Rafael asked.

“Yes, I guess.”

“But not like in my country.” He went serious. “Here they are artificial, here they try too many moves but they just look stupid.”

“That’s not very polite, Rafael,” Colin said.

Rafael looked embarrassed. “Excuse me,” he said.

“He’s right,” Shannon nodded. “They count the steps and most have two left feet. Where do you come from, Rafael?”

“Latin America. You wouldn’t know my country. It’s tiny.”

“Maybe not,” Shannon wondered why he didn’t want to mention its name but she let it pass. “Anyway, I believe the world’s divided into those with rhythm and those without. It doesn’t matter what country you come from. I’ve even met black men who can’t dance,” she paused. “Colin.”

“You obviously haven’t seen me on the disco floor, Shannon,” Colin replied, also pausing before her name.

“I’m looking forward to that. Provecho! Enjoy.” She went back to the counter.

“And that, my dear man, is my friend, Shannon,” Colin said to Rafael, taking a sip of his coffee.

“I agree with her theory about rhythm,” Rafael said.

Colin wiped his chocolate moustache and went back to his newspaper.

Shannon had given Nick a break and was working the coffee machine when the men went to pay. Colin pushed back the sleeves of his work shirt as he took his wallet out of his pocket.

“Your ink’s sick, man,” Nick at the cash register said, glimpsing the anchor tattooed on Colin’s arm.

“Got it when I was young and foolish,” Colin said. “And I wasn’t even in the navy.”

Nick came round the counter to show them his latest tat – a cactus – on his skinny, white ankle.

“Cool,” Colin admired it.

“Don’t encourage him, Colin,” Shannon said.

“What about you?” Nick looked at Rafael.

“None for me,” he shook his head. “Tattoos are only for gangs in my country.”

“I’m with you on that one,” Shannon said, ignoring Nick’s expression.

“Let’s go, clean skin,” Colin led Rafael out, waving as they left the café.

“Can you take over again, Nick?” Shannon went out the back door to grab some soft drinks from a crate. Most of her customers wouldn’t be seen dead drinking such sugary drinks but she needed to be prepared. But then she forgot why she’d come out there; she felt confused and annoyed with herself.

The midwives in their drab blue cotton tops and baggy pants pull my legs wide open. Something is half out of me. It’s a baby’s bottom, then her tiny legs and arms and her head.

“It’s a girl,” one midwife says.

The other takes a photo of her. “Perfect, she’s perfect,” she says.

Perfect? How can she be? She’s struggling. To breathe. She was only in my womb for twenty-one weeks.

I whisper: “Don’t go, don’t leave us yet.” I stretch my arms out for her but the midwife turns away and places her in a tiny crib. The doctor shakes her head. Tom walks to the window, stares out.

“Shannon, I need some help,” Nick’s voice broke through the fog.

“Soft drinks, that’s right.” She found the crate of Coca Cola and lemonade and came inside to stack the fridge. Then she turned the iPod on again. She found a Rubén Blades number, filling her space with the sound of salsa. And she moved in time to the music.

Chapter Two

As Vesna awoke and turned over in the crisp, white sheets, she could hear whistling coming from the bathroom and it dawned on her she wasn’t in her own grotty bed. She was alone as usual but this time in somebody else’s place. Tom, wasn’t it? She thought she remembered his name.

She’d been woken by a dog’s incessant barking. Why do people have dogs if they don’t look after them? Her mind was still half left behind in a dream about a pack of animals roaming the streets of a Kosovo village as crows flew overhead. And why own a dog when you’re living in a city? What was it about Sydney people that they had to have everything?

She surveyed the bare room, dominated by a fireplace with a marble mantelpiece. Once coal was used to heat the house, now a gas heater was inside the fireplace. She gathered it was a terrace house that had undergone a major renovation. A few Aboriginal prints hung on the wall. Desert art by the look of them. That’d be right. Bloody dot paintings. What a trendy! And a clean one too. The place was spotless. He must have a cleaner, who wouldn’t have much to do – there was no clutter at all. Quite a contrast to her own slovenly digs; she was never home so why bother with housework?

It was almost claustrophobically warm; that gas heater really worked. French doors led to a balcony and she guessed rows of courtyards, each with their own pacing dogs probably.

She heard the toilet flush and the memory of the night before returned. She saw the glass of water next to the bed and downed it. How much had she drunk? At least eight wines? Her head was throbbing and she felt dizzy. The evening had started at Sweeney’s just around the corner from her city office and ended in some trashy joint at the Cross. It was all coming back to her. The waiter had insisted: “You have to eat if you want to have a drink here.” So she ordered garlic bread. So demanding for such a dive.

The door swung open and a tall, slim, swarthy man, wearing only a towel around his hips appeared. Vesna was reminded again how much she’d admired his body when she first saw him in the bar and now she was admiring it even more. She didn’t like to think of her own flabby tummy or her bats’ wings. Or as one unkind personal trainer had called them, her tuckshop arms. No wonder she only lasted two sessions. She pulled the sheets and the Laura Ashley doona up to hide them. She really hated her chubby body but she couldn’t be bothered doing anything about it. She made sure the bed linen covered the tattoo of a rose on her chest. Her early forties was perhaps too old for a tattoo but she’d got it when she was young and wild.

“Oh you’re awake,” the man said, not in the friendliest manner.

“Yep. I’m Vesna, how are you?” She let one pudgy hand emerge from under the sheet.

“Tom,” his fingers were long and thin. He shook her hand but didn’t smile.

“Yeah, I know.” Their encounter in a bar with her slipping off the stool came back to her.

“Look I don’t do this …”

“What? Get pissed in a bar and end up with a stranger?”

“No, well.” He looked uncomfortable as he searched his wardrobe for a shirt. Hanging in a perfect line, they were all as clean and crisp as the sheets.

“Why not? Too many knock backs?” she asked from the cosy bed.

He didn’t laugh.

“Look, it’s fine.” Vesna thought she might have gone too far but still stared at him as he dropped his towel and put his clothes on. “Takes two to tango, as they say. My turn in the bathroom?”

He nodded and she swung out of bed, grabbing her clothes along the way, hoping he wouldn’t notice her wobbly bum. She closed the bathroom door. Kids’ toys were on the edge of the gleaming bath and a Thomas the Tank Engine towel was hanging on the rail. Oh no, not an ankle biter, Vesna thought. Ah well, beggars can’t be choosers, even if the man has baggage.

There didn’t seem to be any sign of women’s products though, no fancy shampoos, or moisturisers. No makeup or tweezers even. Or maybe they were hidden away. For a moment she almost stopped herself opening the bathroom cabinet door, but a recent comment by one of her fellow sub-editors came back. He accused her of not digging enough. “What kind of journalist are you anyway?” he asked her. So she looked but found nothing much inside, just some razors and blades and men’s deodorant. Not even tampons. Aha, a packet of condoms – phew, he was separated or divorced. He hadn’t offered to use them last night though. Thanks a lot!

She picked out a clean, fluffy towel from a pile on the shelf, the sort that good hotels provided and that she never owned. The only woman’s touch was a sachet of lavender on the top of the pile. She climbed under the shower carefully avoiding any glimpse of herself in the mirror; the boiling hot water helped drown some of the hangover. Spotting a razor on the shampoo shelf she dragged it through her hairy legs, hoping Tom hadn’t noticed how bad they were.

Outside, Tom was pacing the room, continuously looking at his watch. He had to go to work, and Vesna was using enough water to flood the bathroom.

But Vesna was blissfully unaware of his impatience; she felt slightly better as she emerged, dressed again in her work clothes. “Where’s your kid?” she asked.

“My kid? Well if you have to know, he’s at my mother’s for a couple of days.”

“Oh your mother? So that’s why your place is so clean. And your wife?”

“Wife?”

“You’re wearing a wedding ring,” she took his hand, noticing how perfectly manicured his nails were compared to her ragged ones. “And don’t tell me your mother gave it to you.”

“My finger’s swollen, can’t get the damn thing off.” He pulled away from her. “We’re separated, if you have to know.”

Oh great, a bitter divorce coming up. “What happened?”

“Hey, you’re not a journo are you?”

“Good guess. My interviewing techniques must be showing.” She looked inside her handbag for her brush, dragging it through her thick, dark mane, then depositing the brush back into her bag, complete with her strands of hair.

“What do you do?”

“Lawyer. Where do you work? SBS?”

“Oh God, just because I have a wog name. No, aust.com.au. What do you specialise in?”

“Immigration mainly.”

Tom didn’t offer her coffee or breakfast or mention a future rendezvous. But Vesna wasn’t going to let him get off that easily. “Immigration! You’re kidding. You’re just what I need at the moment.”

“Why, what are you working on?” Tom looked again at his watch.

“I’m doing some Muslim stories, you know how they’re being harassed all the time.”

“Doesn’t sound very digital.”

“I had to convince the features’ editor.”

“You can be convincing.”

“Oh ha ha.” Vesna liked his tone hoping it meant he could be convinced again. “Have you any contacts that could help?”

“I know an interesting Lebanese woman,” he finally answered. “Her name’s Amany. She’s a social worker at the hospital. I’ll email you her number. What’s yours?”

“Oh great,” she tore a piece of paper from her notebook and scribbled down her email address and phone number. “And yours?”

He slowly took his business card out of his wallet. “And by the way I’m a wog too.”

“Yeah, I can see,” she glanced at the card. His last name was Markovik. “Well Kraljevic Marko, your faithful horse, Sarac, awaits you.”

“And you must fly away, Vila Ravijojla, my fellow Saturday Serbian School victim,” he replied.

But Vesna knew only too well the power of ancient Serbian poems and folklore. She well might have been a Vila, a nymph that haunted the woods and springs. She too was not unfriendly to earthly beings but she also could be jealous and capricious. And hungry.

As she opened the door to leave she turned to Tom: “Is there a Macca’s around here? I’m starving.”

Chapter Three

Shannon wiped down the benches and started the coffee machine, the gorgeous smell of roasted beans filling the café. She felt good, for a change. Maybe it was the weather – a warm autumn day with no clouds. Maybe that dark stranger – Colin’s friend – would come in for a coffee, she laughed to herself. That would give her the necessary eye candy to keep going.

A motorbike roared past, its driver in a world of his own. Didn’t matter if there were kids walking to school or mothers pushing prams. If he ran over somebody it would just be collateral. He was on his way somewhere and nothing was going to stop him.

A couple of surfers in wetsuits and tousled, dripping hair stopped just outside the café. They looked bemused as he tore past. “What funeral is he rushing to?” one asked, his skin glistening with drops of salt water.

“Not mine, I hope,” the other, a girl, said and laughed.

Their surfboards still had sand on them. The morning waves were rough and the lifesavers had closed the beach. But that never stopped surfers. A “do not swim, danger” sign was like a red rag to a bull to them. All the more reason to jump in. And it also meant there were no kids playing in the water or yuppies training for their next marathon to stop them catching the wave of the day.

Shannon signalled as she opened her door. “How’s the water?” she asked. “Freezing?”

“About fourteen degrees,” the girl said. “Bloody beautiful.”

Inside, Shannon took out some pastries and bread and turned on the sandwich maker to make a toasted sandwich for her breakfast. As she was popping it into her mouth a familiar car – a black BMW – pulled up. “Oh God,” she groaned. “Knew it.” Just when life was looking good, there had to be somebody to come along and spoil it. Tom. She peered out to see if Maxie was in the back seat, her heart beating. She hadn’t seen him for a couple of days and she was dying to hold his warm, little body. But the seat was empty.

“Where’s Maxie?” she asked Tom as he came through the door.

“Good morning to you too.”

She gave him a questioning look.

“He’s at mum’s. She’s taking him to school. How about a coffee?”

“So now your mother is doing my job?” She threw the sandwich in the bin, filled the jug with milk and steamed it for his usual flat white, wishing she could add some hallucinogenic drug to it. God, he was so straight, in his lawyer suit, boring tie and white shirt. He dressed badly when she wasn’t around to help him choose something just that little bit different from all the other corporates. His mother had probably bought him the shirt.

Such a city boy. Not a wimp. He was fit. He looked good in Lycra, heading off from home on his bike to Centennial Park at the crack of most dawns. But he was a lawyer, an office man in a glassed-in space high up in the city. Not the valley for him, but work lunches, meetings, consultations, cocky tails. An art lover, of course. Member of the Art Gallery. Drinkies amongst the Archibalds.

“Hideous, ugly paintings of hideous, ugly people,” Shannon told him once, but he wasn’t amused. “Come on, let me see your perfect teeth. Have a laugh.” She’d taunted him when he didn’t laugh at her comments. She’d showed off in front of his friends in their suits and ties and cocktail dresses. She knew the names of the painters, their style, their history – she had friends who went to art school when she was a dance student.

The café was filling with people, and a young woman came up to the counter to order, asking what sort of muffins they had that morning.

“The bloody usual,” Shannon snapped.

Tom grimaced. “I think that looks like apple and cinnamon,” he tried to help. “Would you like one?”

“Thank you so much,” the customer said.

“You’re welcome so much,” Shannon said, glaring at Tom as he sat down at a table, staring out the window. She bet he was probably thinking that she was a bad investment. She’d lose the café if she kept putting her customers off like this. Tom’s frown was normal but Shannon noticed something different about him. Was it his smell? He always wore cologne, but not today. He was a bit sweatier than usual too. Or shiftier. That’s it. He looked shifty. As if he had something to hide. And it wasn’t just about keeping Maxie. Must be screwing around. That’d be right, couldn’t keep his prick in his pants. Ah well, the marriage was over. She knew Tom thought she was mad and just too much hard work. Maybe his mother was right, she was a bit crazy.

Her phone rang and she took the call. One of the greenies she knew from the valley; they were organising another sit-in to protest against the cutting down of trees for the new highway.

Maxie kept begging to go down to the valley. The old farm house was close to the rainforest, the nesting ground of lyrebirds whose sounds mimicked those of the calls of all the birds in the forest, weaving a tapestry of song through the trees. She’d taught him the names of the birds. Already he could pick them out from an ancient book she’d kept for him. He loved the satin bower-birds the best, with their crazy bowers next to moss-covered rocks or fallen logs. He’d put out blue bottle tops and pegs just to see if the bower bird found them and ferreted them away to his bower.

“Sorry I can’t make it down this weekend,” she told the greenie. “Next time, OK?” She felt slightly guilty as she served the woman customer her coffee and muffin and brought the flat white over to Tom, pulling up a seat and sitting down for a minute. Well, she couldn’t be everywhere.

“Don’t forget to bring Maxie on Friday,” she said to Tom. “It’s my weekend.”

“Ah, that’s why I’m here. Shannon, I think he’s better off at mum’s. He’s having a good time there. And it’s dad’s birthday on Saturday.”

Shannon’s face dropped. She knew the day was looking far too benign. Something just had to happen. She turned away; she didn’t want Tom to see how easily he could affect her. And why wasn’t she invited to the old man’s birthday? They got on well; she liked him and he liked her. “What do you mean? My lawyer said …”

“Your lawyer?”

“Yes Tom, my fucking divorce lawyer.”

“Don’t swear Shannon, calm down.”

A couple of women with blue-rinsed hair sat at the table next to Tom. Where was Nick when she needed him? Late as usual. She noticed the women look up at the raised voices, but she didn’t care. “Tom, it’s my weekend.”

“Next weekend, OK?”

“Tom!”

“Your customers, Shannon, keep your voice down,” he whispered.

“Don’t tell me about my customers.”

“Look, I think it’s better for him to stay there most of the time,” he stirred his coffee. “I’ve had to work late a lot.”

“Well, bring him back here. For Christ’s sake, I’m his mother.”

“You’re still not coping.”

“I am. I’m much better. I can manage.”

“Just give it a little bit longer, Shannon.”

“How much longer? Come on, Tom.”

“A few more weeks.”

“No! I want him back. You’re in breach of the arrangements. You’re a lawyer, you should know.”

“Yes, Shannon, don’t forget, I am a lawyer.”

“Yeah, a fucking Immigration lawyer.”

Rafael was smiling as he came in the door of the café but he stopped at the sound of the argument. He turned around quickly and went back outside.

Shannon saw him. “Tom, I do have to look after my customers. Do you mind?”

“OK, but please be reasonable.” Tom gulped down the dregs and scuttled out the door.