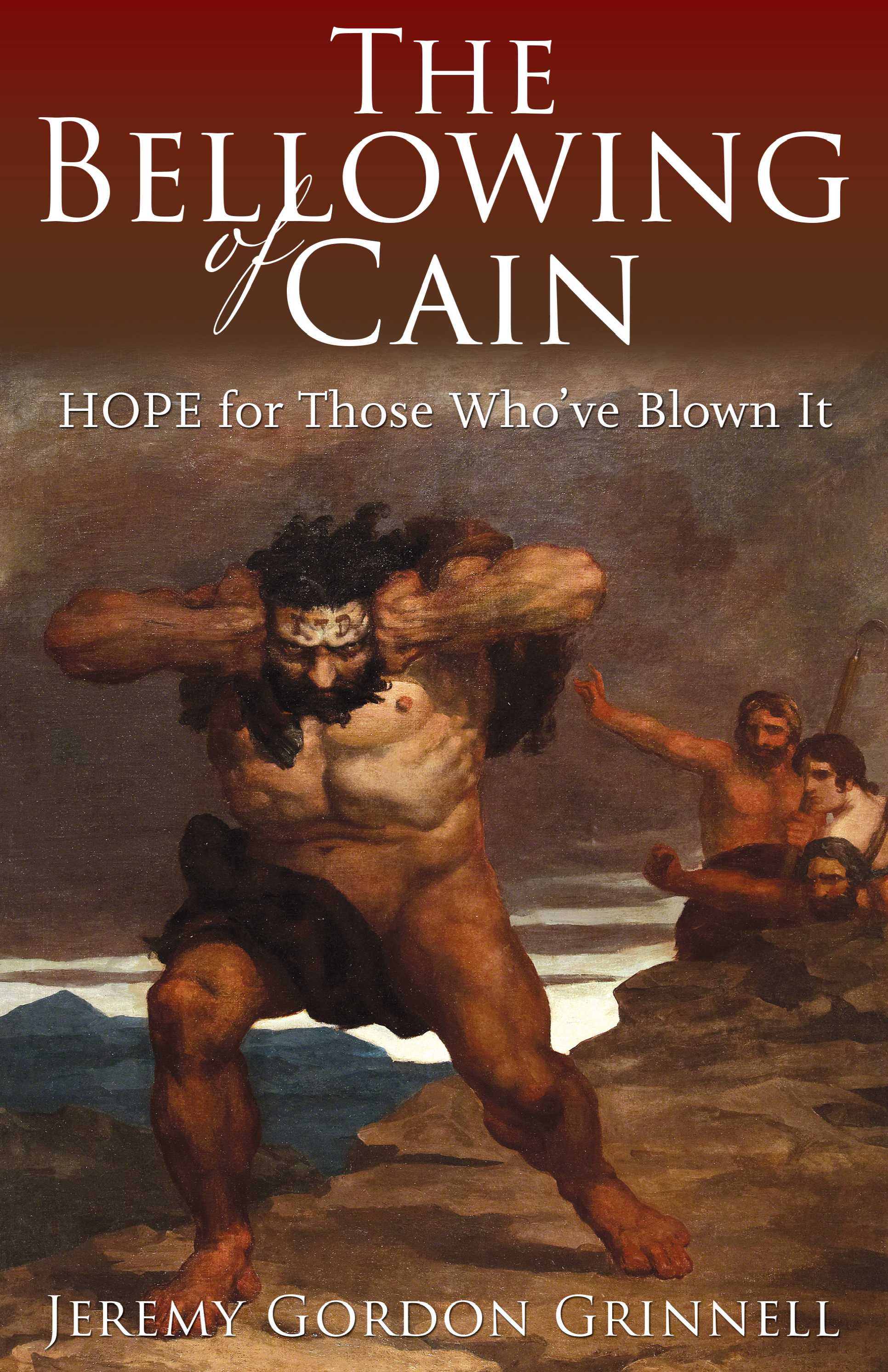

Introduction: Cain Speaks

Once upon a time there were two brothers. The older’s name was Cain, and the younger was called Abel. Now, in the course of his life, Cain experienced a great disappointment with his God, and in the midst of the agony of his soul, he decided somehow his brother was the cause—or at least a constant reminder of it. So it came to pass …

Cain said to his brother Abel, “Let us go out to the field.” And when they were in the field, Cain rose up against his brother Abel and killed him.

Then Yahweh his God said to Cain, “Where is your brother Abel?”

He said, “I don’t know; am I my brother’s keeper?”

And Yahweh said, “What have you done? Listen; your brother’s blood is crying out to me from the ground! And now you are cursed from the ground, which has opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. When you till the ground, it will no longer yield to you its strength; you will be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth.”

Cain bellowed, “My punishment is greater than I can bear! Today you have driven me away from the soil, and I shall be hidden from your face; I shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth, and anyone who meets me may kill me.”

Then Yahweh said to him, “Not so! Whoever kills Cain will suffer a sevenfold vengeance.” And Yahweh put a mark on Cain, so that no one who came upon him would kill him. Then Cain went away from the presence of Yahweh and settled in the land of Nod, east of Eden.

—Genesis 4:8–16, adapted from the NRSV

I used to teach systematic theology to seminary students. It doesn’t matter what systematic theology is—at least it seldom mattered to my students. They only wanted to know whether I could answer their questions about Christianity and the Bible. If I could explain hard things in simple terms. They wanted to know not if something was true (although that occasionally mattered) but whether it was useful. While this is bound to annoy a professional theologian, in fairness to them, it is possible for a thing to be both true and irrelevant.

I spent a lot of class time working with the stories in early Genesis—the creation of the world and humanity, the fall into sin—for exactly these reasons. While students sometimes struggled with how these stories could be true, they seldom questioned that they were useful. They are the Christian explanation for most of our human experience.

First, they reveal why so many things in life are good and beautiful. A good God made all these good things so humans might use and enjoy them in ways that display God’s glory in the world. Second, these stories explain why the world we inhabit is so filled with wretchedness and sorrow. Humanity rebelled against this good God, shattering both themselves and all that had been entrusted to their care—which was everything. Further, these stories even speak of redemption. God declares that broken things can be restored—promises, in fact, that they will be restored, not by mere human efforts but by that same good God stooping down to work through human hands. This is the first hint of a redeeming Messiah.

I rehearse all of this because this book is specifically about the difficulty we have moving from the second to the third movements of the story—from Fall to Redemption.

My students were usually more interested in the transition from the first to the second movement—Creation to Fall. They would ask how Adam and Eve’s eating an apple—admittedly a small thing—could cause the whole world to go to heck in a handbasket. The punishment seems so much greater than the crime. Our hearts stiffen under the idea that small mistakes can bring such great destruction. It doesn’t seem just. I understand the question, and while I believe good answers exist, I admit that on the surface, it chafes.

But our expectations about justice are fickle. Not once in my fifteen years of teaching graduate theology and many years of pastoral ministry did anyone ever ask the same question of Cain’s fall from grace. I have heard Cain called a whiner. I’ve heard him labeled impenitent. I’ve even heard him called fortunate because his punishment should have been harsher. In his first epistle, St. John even makes Cain, rather than his father, the ultimate foil to Christ. Following John’s example, early church writers use Cain as the archetype of the Fall at least as often as they so speak of Adam. He is even considered by some the father of an entire line of evil descendants, standing against the righteous line of his brother Seth. In this view, the children of righteousness are always persecuted by the children of evil—in other words, the unredeemable children of Cain.

I do not dispute the truth or usefulness of any of this. I don’t wish to downplay the evil Cain did in any way. I don’t question whether his punishment was just. But I am intrigued by our lack of curiosity about what became of him, of his emotional and spiritual journey after his banishment.

He goes “away from the presence of Yahweh” and is an outcast. That is the end of our knowledge of and interest in him. We don’t care if his heart ever changed. He is just an outcast. We’re not curious about any lessons his banishment may have taught him. He is just an outcast. We’re not concerned about the nights of solitude, shame, and sorrow that were his. We don’t care, because he’s just an outcast. He may bellow his grief and misery at a cold and indifferent sky, but no one is there to hear. He is the archetypal perpetrator of evil and as such lies beyond redemption.

Yet Cain’s journey matters desperately to me, for I am like Cain. I, too, have cause to wonder whether I really can move from Fall to Redemption. For all our pious rhetoric, I wonder, is redemption really available for people like Cain—people whose wounds are entirely self-inflicted?

I also bellow and get no reply.

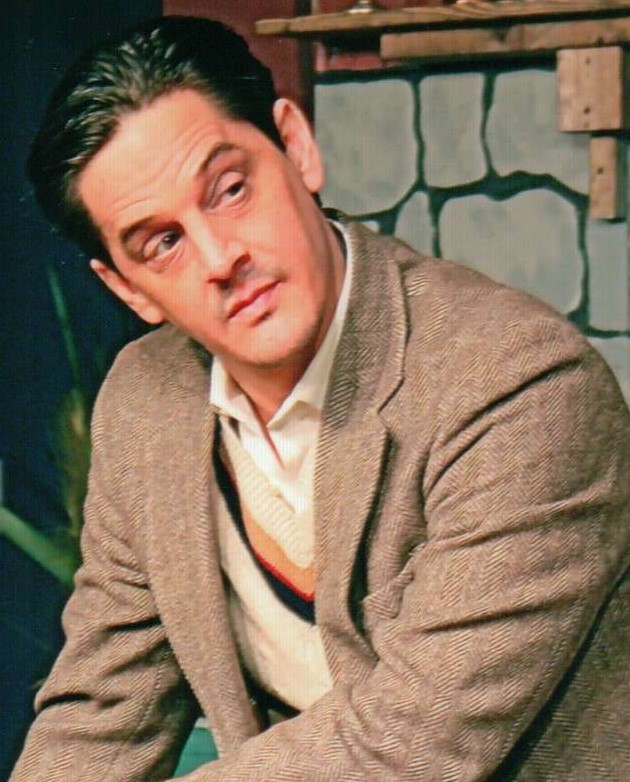

A Son of Cain

I no longer teach at a seminary. I no longer pastor a church. I’d like to say the details don’t matter, but they do. If all you knew about Cain was his exile, you would wonder, Exiled for what? And you’d be right to wonder. Cain’s crime was not a small thing. It does matter. So I will lay out my failures here at the beginning (with more detail to come) so that you can understand why Cain now matters to me.

In 2013, I was justly convicted of surveilling an unclothed person.

That’s right. I’m a peeping tom.

If it reddens your cheeks a little bit to contemplate a seminary professor and respected pastor doing such a thing, I’ll understand. I’m still surprised by it myself. It’s not the sort of thing a younger me would have expected to be part of my biography.

Sadly, however, it is not the worst thing I did. Oh, in a legal sense, it was, insofar as I broke no additional laws. But in a moral sense, the ten months preceding that choice were far worse. That was the season of the premeditated emotional affair, wherein I betrayed my wife, my children, my students, and my congregation. I lived a tortured double life—a life I both hated and freely chose. The first part of this book is the story of how I ended up there—how I became like Cain and “murdered” the closest relationships in my life.

Naturally, there is more to the story. There always is. But I don’t want any of the subsequent context—a word often used to deflect one guilt—to imply that I was not responsible for my actions. This is a record of my choices and my failures. The context is only important for understanding how we get ourselves into the position where such self-destructive choices seem viable. The context is the warning. It’s the school room in which, if we pay attention, we can learn the lessons that will prevent such failures in both ourselves and others.

Regarding this larger context, I think I made my best attempt at articulating it several years ago. A major Christian publisher had expressed interest in publishing my dissertation. That was gratifying. But I also knew it was no good trying to go forward without their knowing my backstory. I crafted a delicate email knowing that hitting Send would cause them to retract the offer. Nevertheless, I wrote …

That you are prepping a contract for my dissertation is a significant step forward for me. I have told you I left the academic world under a cloud, and so long as I was only doing [uncredited voiceover work for your publishing house], the details of my story didn’t seem relevant.

But we’re entering a new phase wherein our reputations will depend on each other for success, and after much prayer and conversation with my wife Denise, I think it is important to give you more details lest you ever think I’ve not been forthcoming with you.

In 2013, I endured a ten-month clinical depression in relation to a woman Denise and I were attempting to help through a home foreclosure and legal battle. I lost track of personal boundaries and became fixated on her and her family’s needs. She further encouraged this obsession. It nearly destroyed my marriage and my health.

Ultimately the depression and obsession led to an indiscriminate invasion of privacy (a David-like case of being in the wrong place at the wrong time and not walking away when I should have). It was not done by design, and I attempted to resolve it with both a confession and a placing myself under the discipline of the elders, and even offered my resignation of my pastoral responsibilities at the church. Exercising her legal rights, however, she decided to press charges. The press got hold of the story, and I was publicly shamed. After which I also resigned my professorship from the university. Ultimately, rather than prolong the agony for my family, I took a plea deal, and the judge, apparently realizing the convoluted nature of the case, gave me only probation. But the public record remains … and is ugly.

The depression mercifully broke, and my marriage was restored, but it was the beginning of two very dark years of almost total isolation. To go from a career in ascendance to unusable and unwanted was almost more than I could bear … But God is good …

This is what I wrote then and have included here as written except for the name of the publisher and certain personal details about the woman, who for the sake of her privacy, I will hereafter refer to as “Lorelai” after a television character to whom she bore a vague emotional resemblance. Even as I reread this account, I don’t think I could improve on it for brevity or emotional distance. Of course, such a story would sound very different coming from Lorelai, or from the elders of my church, or from the dean at the seminary, or from Denise—especially Denise. I admit this. But all stories must begin somewhere. The rest will come as needed.

Why This Book?

So now I’m a child of Cain. I don’t mean I’ve ceased to be a Christian, nor that God’s love for me has slackened, nor that I feel I am beyond forgiveness. I mean that like Cain, I, too, was thrust beyond the sphere of human society because of my sin. I have bellowed at the consequences of my choices—both those that were organic and expected and those that seemed beyond the realm of the bearable. And so I ask again, when we speak of the third chapter of the biblical story—the redemptive chapter—does it exist for people like me? Am I alone in such questions?

I don’t think I am.

One of the most shocking things about my journey is that in the first three years following the implosion, I had more people tell me about their own comparable journeys than in the fifteen years preceding it. I can explain this only by means of a gently cynical observation that once you’re damaged goods, other people feel you’re a safe person with whom to share their own failures. After all, who am I to judge?

I’ve had people confess to me they’ve done exactly what I was convicted of, only they’d never been caught. I’ve had pastors, missionaries, and schoolteachers confess their own emotional (and occasionally physical) indiscretions and their overwhelming ulcer-inducing fear, knowing if anyone ever knew they would be out of their positions and unemployable forever. I’ve listened to wives and husbands going through the same feverish obsessions over everything from losing their youth, to losing their respectability, to losing their legal freedom. I’ve seen their fear. The fear of being found out, of forfeiting everything. They live in terror of someone asking, Where’s Abel? because they know each repetition of the lie upon which their survival depends only deepens their guilt and shame.

I’ve seen the hunted, lost look in their eyes because they know that when it all comes out, it won’t matter what demons they’ve struggled with. It won’t matter how long they’ve fought to keep those demons under control. It won’t matter that they did everything in their power to do the right thing even as they were also doing the wrong thing. It will make no difference at all. In the eyes of everyone, they will be the perp, and all sympathies will be with the victim. They will be cast aside.

They are not wrong to fear this.

This is what will happen.

They will be like Cain.

If you have such skeletons hiding, or if they’ve been dragged out and put on display on your front lawn, you know the terrors of which I speak. This book was written for you—the perpetrator, the shamed, the fugitive, the outcast. I wrote it so you may know that you are not alone. There is hope. Others have walked this road … and have survived.

Why Focus on Perpetrators Rather Than Victims?

Now, if you’re a child of Cain like me, you’re probably suspicious. Who has sympathy for culprits and malefactors? Most books on surviving trauma deal with the victim. They ask how to survive the troubles that come from without—the diagnosis you received, the abuse you endured, the layoff you didn’t deserve. Such books want to help a person grow through injuries that are not their fault.

But that’s not you. That’s not me. Our wounds are self-inflicted. We’re the ones people blame for their pain. We’re the ones people shun because we are at fault. Abel is dead, and we’re the ones with blood on our hands. Why worry about us when there are victims to be comforted?

The question is fair and right.

This is one of the hard truths we have to accept as a starting point. Our choices have forfeited people’s sympathies. They are correct to sympathize with victims. Their attention is on Abel.

And it should be.

Cain’s losses are what he deserves, and it is just. I cannot disagree. Cain is guilty.

Yet even after I’ve agreed with God that Cain’s punishment was just, a leftover remains. Even after I’ve remembered that Abel lost far more than Cain. Even after all the pain Cain caused his parents, his brother, the human race, and his God is accounted, a drunken sentiment still staggers around my heart crying, But poor Cain.

And now that I know Cain’s feeling from the inside …

Now that I know his need to bellow at the weight of his punishment …

Now that I know the hideous shame standing behind that cry and all it tries to hide, I cannot turn my back to it. Nor can anyone who has ever made a horrible choice and lost precious things.

We must write books such as this. We must write to perpetrators as well as to victims. Not the same books, perhaps, but Christ’s death was not only for victims. The cross was a criminal’s death, meant to atone for criminals’ deeds. A gospel of reconciliation demands a place on the shelf for this book next to all those that offer help to victims.

No book—certainly not this one—can release Cain from what he did. He did it. He must own it. Rather, the goal of a book like this is to put words to Cain’s cry—and to yours—so you will know you are not the first to bray uselessly at the universe and, in that knowledge, find hope.

Final Comments Before Beginning

The following chapters form a kind of chronological development in three parts or movements. Part 1 offers reflections on the various defenses breached in the run-up to self-destruction. Part 2 discusses what it’s like to watch your world crumble around you and how to face the immediate consequences—the short game. And the final section, Part 3, offers hopeful thoughts on rebuilding a meaningful life after all the immediate furor has died down—the longer journey.

As this implies, I’m addressing two types of people. First and primarily, the person who, like me, once worked in a “Christian organization”—the former pastor, church staffer, missionary, teacher, university employee—and is reeling from self-inflicted damage that has cost them their career. As you read the first section, you may well ask, Why is he rehearsing the run-up to destruction? It’s too late for me. That’s not what I need. I’m sorry to disagree, but that’s actually the first thing you need. It’s not about just standing back up where you are. You also need to think about how you ended up on the ground. The first section of this book is just as important to you as the others, because you blew up your life for a reason. Something caused it. If you don’t figure that out, you’re in for an encore performance.

The second reader I’m speaking to is the ministerial student, the commissioned missionary, the serving pastor, or church/parachurch staff member. For you, this book is a crash course in prevention—particularly the first section. I want you to know the warning signs, both in you and in others. I want you to avoid Cain’s fate. The later sections on rebuilding should have pastoral value as you work with Cain’s children in your communities.

But there is a third possible reader—the victim. Are you one of those hurt by Cain—the spouse, the friend, the congregant? In no way do I intend to marginalize your suffering. It is real, and I would not detract from it in the least. Your wounds are of central importance, but I hope you can acknowledge even through your pain that yours are not the only wounds that need the gospel. Though our wounds are different, Christ’s healing work was for all of us—victims and perpetrators alike. So please understand that this book was not written primarily to you and parts of it will be painful to read. But if you’ve still determined to read it, my prayer is that it will give you a glimpse into the soul of the one who hurt you. That can sometimes facilitate healing.

To restate the central question, then, What’s Cain to do? Can he find his way back into the human fold, or does he bellow in vain? Tragic literary figures may deserve what they get, but they are still tragic. Is redemption a mere idea or a real possibility? Is there hope for Cain?

If in the end redemption does not exist for the worst of sinners, it exists for no one.