Part 1: Sunshine and Clouds

Chapter 1

Clouds

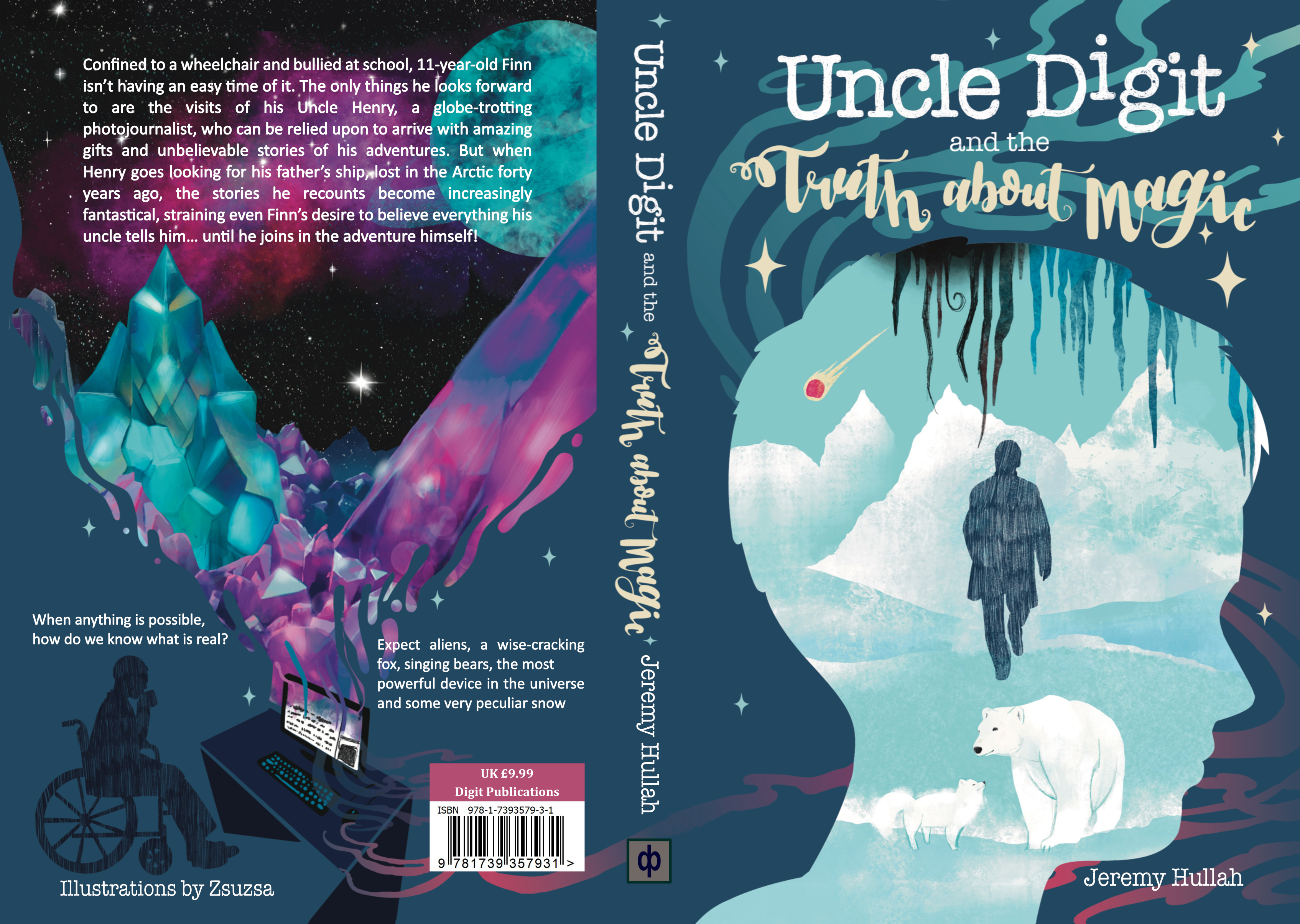

This is a story about stories and the magic of stories.

This is a story of singing bears who speak in dreams and of beings made of light and darkness whose battle for power could destroy the world.

Although I become a part of this story, it’s not my story; it’s the story of my uncle – Uncle Digit.

The story happened more than forty years ago when I was a boy, in a time when there was no internet or social media, and if anyone mentioned ‘climate’ and ‘change’ in the same sentence, they were probably talking about the leaves turning red in autumn.

Even after all this time, I can close my eyes and smell the sharp tang of fresh oranges being squeezed for cakes. I can hear the clatter of bowls and pans in the kitchen as my mum cooked, and I can feel the youthful excitement of an eleven-year-old boy, as he sat in his wheelchair, listening to his uncle telling him incredible tales from around the world.

Our home was a large, terraced house full of our family history. My grandparents had moved there after they were married, just before the Second World War. There were photos of them on sideboards and mantelpieces throughout the house: Alfred and Lily on their wedding day; Alfred in his Petty Officer’s uniform before being shipped out to war; Alfred and Lily holding a very tiny Uncle Henry; Alfred with a kit bag on his shoulder as he left for an expedition a few years after the war – an expedition from which he would never return.

When Lily died suddenly at the age of fifty-five, Mum and Dad came to live in the house and I was born a few years later – Finnegan Starling Wake, or Finn for short. My father was Richard Wake and the Starling came from my mother, Tibby Starling. Mum said that Finnegan was only meant to be a ‘working title’ while she was pregnant, as it was a joke about some famous book. In the end though, they decided they liked Finn better than any other name and I was stuck with it.

A lot of the furniture, books, ornaments and vases in the house were remnants from Alfred and Lily and they had their own stories that Mum would tell me over and over. There were books that Mum read to me that her mother had read to her as a child. An old oak settle in the hallway that had belonged to Lily’s father used to be Mum’s favourite hiding place when she was a girl and some of the vases had little labels on the bottom, with tiny writing, showing where and when Alfred and Lily had bought them.

Mum and Dad’s stuff nestled inbetween the older furniture and artefacts in a cosy jumble of styles that hadn’t changed for as long as I could remember. Photos of Mum and Dad’s wedding, holidays and me, sat alongside photos of Lily and Alfred or Uncle Henry.

There was a good-sized sitting room downstairs, but that was only used to watch telly as we spent most of our time in the kitchen.

The kitchen took up half of the ground floor with a large range, hanging rails for pots, pans and ladles, and shelves full of jars of dried ingredients and spices. There was a huge dresser, jammed full of glasses and crockery, and a table in the middle of the room big enough to seat ten people.

Mum spent a great deal of time in the kitchen and it is there that my fondest memories lie; among the smells of the herbs and spices simmering in saucepans, and the light shining through the flour in the air as Mum baked bread, pies and sweet puddings.

She was always calmer when she was cooking. It was in the kitchen, more than anywhere else, that I heard her laughter, like the sound of glass bells, brightening up the room. It was cooking that allowed her time to relax, and to forget that my dad had been taken from us and I’d been left paralysed by a car accident when I was four. To forget that we had very little money, because she was only able to work part-time and occasionally had to take in lodgers to make up the shortfall.

The lodgers stayed infrequently, but when they were there, they cast a shadow over the whole house I couldn’t escape from, even in the kitchen or my own bedroom. Most of them were pretty decent, but some weren’t very nice at all. I remember one running out of the house, clutching his bag and a bloodied nose, screaming something about fetching the police and that Mum should think herself lucky someone was prepared to even look at her, considering.

“Considering what?” I asked Mum, confused. But she just gave me a big hug and sobbed into my shoulder. Those were the worst times. I would try my best to cheer Mum up by writing little stories about each lodger after they’d left. There was Awkward Andy, who broke things, and Skinny Simon, whose knees creaked and cracked as he walked. Then there was Huge Harry, who loved his little sports car more than anything in the world. But the car was too small for him and I wrote about him trying to fit in it with everything popping out and flying everywhere. That made mum laugh for a week.

The other thing that cheered her up was her brother coming to visit. I could always tell when he’d arrived, as Mum let out a little squeal of delight when she opened the door.

He would burst into the kitchen to say hello and I would almost jump out of my wheelchair with excitement. It was like the sun coming out after a month of rain. You forgot what it was like to be wet and miserable, and just enjoyed the bright sunshine and warmth.

My uncle talked endlessly about his adventures, making grand gestures with his arms as I sat motionless in awed silence.

Mum would laugh, saying, “Oh, for goodness’ sake, Henry! You’ll have Finn believing you’ve actually done all those things.”

He’d always smile broadly and wink after telling his stories, and this confused me – I didn’t know if it meant he was making them up or not. He would look at my puzzled face and laugh as if it were the best joke in the world. But once or twice he would tap his nose when Mum had left the room and whisper to me, “You know that the wink’s just for your mother, don’t you, Dear Boy? It’s all true, every word of it, but I wouldn’t want her to get upset thinking I was actually running around doing mad things all the time, eh! So, just between you and me, okay?”

If he wasn’t telling me his real-life adventures, we would be making up stories and sketches of our own. Like the spitfire pilots, meeting up after the war in reduced circumstances, always trying to show each other that everything was still ‘tickety-boo’: “I haven’t sold the Jag dear boy, I’ve just lent it out to some film types who needed it for a shoot.” And I was as likely to be called ‘Dear Boy’, ‘Champ’, or ‘Sport’ after the characters in these stories as by my own name.

Every time he came, he would bring something for me from his travels; sand from inside the great pyramids that no one had walked on for five thousand years, or bits of fossilised trees from the lost forests of Namibia, now nothing but dried-up waterfalls and deserts. He told me he tried to bring me something far more precious; that on the coast there were dunes where the diamonds lay on the surface of the sand and you could see them clearly at night as they glistened in the moonlight, but they were heavily guarded and he was chased away before he could get one.

Once, he brought me a squashed-up bullet that had missed him by two inches when he was covering a war in Lebanon, which he told me I must never show to Mum.

Each present was the starting point for one of his fantastic stories, which I would listen to with eager ears and wide-open eyes.

When he left, I would be sad for days. Mum would have to work extra hard to cheer me up, even though I’m sure she’d have loved him to stay for longer as well.

“Can’t you come and live with us?” I asked him. “You always give Mum some money when you leave, so why don’t you just stay here all the time and look after us properly?”

“I couldn’t do that, Finn. I’m just not reliable enough,” he said. “I’m never around. There’s nothing I’d love to do more, though. You know that, don’t you? But I need to earn a living as well.”

He was a photojournalist. At the time I didn’t really know what that meant, or how a photojournalist made a living. I knew he did, of course, because of the extra money he gave Mum. Once, this was quite a lot and Mum stood there looking at the roll of notes in her hand.

“Henry, this is far too much,” she protested. “What are you going to live on?”

He folded her hand gently over the money, saying something about selling a lot of pictures.

Sometimes he would look like he hadn’t eaten or changed his clothes for a week, but he would always have something for Mum.

Then came the day it all started.

I’d just had an argument with Mum and she’d stormed off to answer the front door, leaving me in a mood that lifted only slightly when my uncle put his head around the kitchen door a few minutes later.

His beaming smile faltered when he saw me struggling to raise one of my own.

“What’s up, Champ?” he asked, putting a magazine down on the kitchen table.

“It’s nothing,” I said, knowing he wouldn’t believe me.

To avoid meeting his eyes, I looked at the cover of the magazine he’d put down. It was a photograph of a young girl standing in front of some ruined buildings.

“Did you take this?” I asked.

“Yes, I did.”

“It looks so unreal; like it’s another world.”

“In a way, it is another world, but it’s very real, I can assure you.”

“Why do you have to go so far away?” I asked, with more frustration than I meant to. “Why can’t you just take photographs around here?”

“I wish I could,” he said, kneeling down in front of me. “But it’s not as easy as that.”

“Why not? If you were here, Mum wouldn’t have to take people in,” I blurted out, sinking down into my chair, as if this would make me invisible.

It didn’t matter that there weren’t any lodgers at that time; word got around school and there were always the occasional taunts, especially from Percy Simmons and Jasper Anderson in the year above. They called me ‘Spinny’ and delighted in seeing how long it would take before I started shouting at them, knowing that I couldn’t get out of my chair to give them the thumping they deserved. But that day I didn’t say anything.

“How much do you think Spinny’s Mum charges the lodgers, Percy?” Anderson asked Simmons casually as they walked past me in the playground.

“Well,” said Simmons with a pretend look of shock on his face. “I’m sure I can’t guess. My mum says it depends what additional services she offers.” And they both creased up laughing.

I had no idea what they found so funny, but I knew it wouldn’t be anything pleasant.

“Or maybe,” continued Simmons, as though thinking hard about something. “She just needs the company.” He jutted his bottom lip out in mock sadness and pretended to cry. “She’s been so very, very wonelee since she lost her husband.” And they fell about again.

Before I knew it, I was charging towards them as fast as my hands could turn the wheels of my chair. Simmons and Anderson were too busy laughing to notice and I got right between them and knocked them over onto the hard tarmac surface.

Simmons was the brains of the pair who never got his hands dirty. He was looking shocked and was backing away on his bottom with one of his hands, the other feeling the blood oozing from a graze on his head. Anderson was the henchman and would think nothing of stamping on someone’s foot to force them to give him their Mars Bar. He picked himself up straight away and launched himself at me, toppling me over and getting caught up in the wheels in the process, before the playground teacher came and separated us.

Mum was called in for a ‘chat’ after school. When we got home she let me know exactly what would happen if she was ever called in again.

Uncle Henry was looking at me, but I was staying stubbornly silent.

“Your mother tells me you got into trouble at school today?” he said, eventually.

I was shocked. Why had Mum told him? That made everything so much worse. I imagined sinking even lower into my chair, falling through the house and through the earth, into some lost world of caverns where nobody could find me. But it was no use; I could still hear my uncle talking. “Don’t you want to tell me what happened?” he said.

No, I didn’t.

“Didn’t Mum tell you?” I said, my head firmly lowered onto my chest.

“Yes, she did, but I want to hear it from you.”

“Why? It’s not going to change anything, is it?” I shouted, right into his face, unable to stop myself. “They deserved it. They were saying horrible things about Mum and the lodgers!”

He pulled up a chair and sat down, letting me calm myself for a minute until I felt bad for shouting at him.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to shout at you. Sometimes I just want things to be different and I’m angry when they’re not. Is that wrong?”

“It’s not wrong to want to change things, Finn. It can be a good thing that helps you develop and become a better person. But it’s also important to know what you can change.”

I didn’t say anything for a while, allowing his words to sink in and calm me further. I found myself staring at the photo of the girl on the magazine cover. Her dark hair was matted and covered in dust, her clothes were frayed and torn, and she was holding a doll tightly to her chest. The most striking thing about her were her searing blue eyes, which were looking straight into the camera, challenging you to an impossible staring competition.

“Who’s the girl?” I asked.

“She’s a princess,” replied my uncle.

“She doesn’t look like a princess.”

“Really?” he said, looking at the picture as if for the first time. “Yes, I see what you mean. But look closer and you’ll see the camera shows more than just dirt and torn clothes. What else can you see?”

I looked again, but I could only see the buildings and the girl.

“What was the first thing you noticed when you looked at it?” he asked.

“I think it was her eyes,” I said.

“When you look at her eyes, what do you see?”

“She looks angry.”

“Yes, and anything else? Does she look afraid?”

“Not really; she looks defiant, as if something’s burning inside her, like fire.”

Uncle Digit smiled. “I couldn’t have put it better myself, Dear Boy. I got to know this girl a little and I got to know her fire a bit more. It was her courage, her strength and her heart that made her a princess.”

I was still looking at the photo, wondering at a life so different from my own.

“She reminds me of a fairy tale your grandmother used to tell me and your mother when we were young,” my uncle continued. “She called it ‘The Truth About Magic’. I’d ask her to tell it to me whenever I felt a bit like I think you do now. Has your mother ever told it to you?”

“Not that I remember, no.” I wasn’t sure how a fairy tale was going to help me.

“Do you want to hear it?”

I shook myself out of my doldrums, reminding myself that even though this wasn’t going to be one of his amazing stories from his travels, just listening to my uncle talk made me feel better.

“Yes, please,” I said.

And my uncle told me the following story.