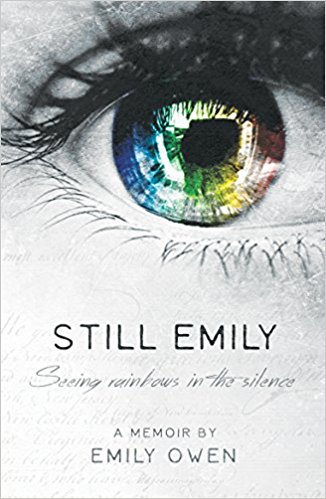

Still Emily: Seeing Rainbows in the Silence

Prologue

I picked up my flute and walked into the examination room.

The examiner, unsmiling, pointed me to a music stand in the middle of the room.

He told me to begin.

Placing my music on the stand, I raised my flute to my lips.

Inner voices jostled for my attention.

My child-self: “I want to learn to play the flute”.

My music teacher: “You’ve got real talent”.

My conscience: “You should have practiced more”.

The impending scales, my nemesis, mocked me.

The approaching aural tests, ‘free points’ for me, reassured me.

As did the sight-reading.

The examiner cleared his throat, “Begin your first piece whenever you’re ready.”

I was always ready as far as music was concerned!

And so I began to play.

After a few weeks, the results arrived: I’d passed.

More than passed, I’d done well.

But not as well as I should have.

Next time, I told myself.

Next time I’ll practice…..

One day, 5 years later, I woke up in a world of silence.

……

At the end of 1978, a young woman discovered she was pregnant.

“Dear God,” she prayed, “Please don’t give me a disabled child. You know I

wouldn’t be able to cope.”

In May 1979, her baby was born.

Gazing down at the healthy child she held in her arms, she realized that God had

answered her prayer.

She looked up and whispered, “thank you”.

The woman was my Mother.

The baby was me.

.............

I was 5 years old when my parents decided to follow a family tradition by

sending me for piano lessons. I remember sitting on the piano stool, legs

swinging, feet that didn’t touch the floor. Little fingers that could hardly span the

keys but that would grow to span an octave plus three notes, something of which

I would be very proud!

I loved playing the piano but I wanted to play pieces I wanted to play, not the

exercises my teacher gave me to practice at home. But that was okay; after a

quick half hour at the piano before I went to my lesson, I was able to play the

exercises and my teacher never knew that I didn’t practice much.

Or so I thought.

When I was 8, the teacher took my Mum aside and told her that I could go far if

only I’d practice….

.............

Mum introduced me to music and Dad introduced me to sport. He loved running

and so, I discovered, did I. It became a regular thing for Dad and me to put on

our running shoes and go for a run around the local park together, him slowing

his pace and encouraging me to keep going.

...........

The summer I was 12, I was enrolled on a daily riding course for a whole week.

This was a big deal.

Partly because I would finally get to ride but more because of the expense.

With four children, money was tight in our house and yet my parents managed to

scrape together enough for me to go.

I had a great week. Over dinner every night I would give my family minute by

minute accounts of all I’d done. I talked about the grooming, the saddling up, the

cantering, the jumping….but I never mentioned the bullying.

The bullying started on day one and it baffled me.

I wasn’t rude to anyone.

I didn’t hurt anyone.

I kept myself to myself.

So why pick on me?

As well as being baffled, I was hurting.

Those bullies were really mean.

Every day they goaded me, taunted me, pushed me.

But I didn’t tell anyone.

How could I?

My parents had saved so hard for me to ride.

So I kept the bullying to myself.

I didn’t tell my family that I was greeted with ‘shut the door in front of you’ when

I started to board the bus that took my group from the drop-off point to the

stables.

I didn’t tell them that no one would sit with me on the bus.

I didn’t tell them that I dreaded getting to the stables.

I just told them that I loved being there.

Basically, I started compartmentalizing.

I would have imaginary boxes in my mind and choose which one to try and focus

on. I still thought about the bullying, of course I did, but only sometimes. The

rest of the time I did my best to keep the bullying lid firmly on the box and focus

on the ‘horse box’ instead.

This ability to compartmentalize has proved invaluable in my life, particularly

when circumstances threaten to overwhelm me.

As well as enjoying sport and music, I enjoyed school. I loved learning. Except

for maths. Numeracy was never my thing, much to the despair of my maths

teacher father! Apart from maths, I was in that rather strange group of people

who are actually pleased when the teacher announces an exam, relishing the

opportunity to test myself.

When I was 14, I began studying for my GCSE exams alongside playing in the

school band and orchestra and being a member of various sports teams:

running, hockey, gymnastics…

During one gymnastics competition, I slipped off the balance beam, ending up in

hospital again. I didn’t really mind not being able to complete the competition. I

was too tall to be a good gymnast anyway, and had only really been put on the

team to make up numbers.

But that slip was another unheeded warning sign.

Around this time, I joined a Philharmonic Youth Choir which was being

established in my city. I had sung in choirs and singing groups from an early age

but this one was different. We sang a wide range of musical genres to a very high

standard; we performed in amazing places and concert halls, we sang in

competitions and we went on trips. One of these excursions was an outing to

London. Our current repertoire involved songs from Andrew Lloyd Webber’s

‘Starlight Express’, so it was a great excuse for us to go and see the show. And

what a show it was! I remember being particularly amazed by the cast whizzing

around on roller skates, up and down the aisles amongst the audience.

One of the songs contains the lyrics, “There’s a light at the end of the tunnel”.

As I sat in the theatre and listened, I had no idea that I was soon to enter a very

dark tunnel indeed, let alone whether there was light at the end.

................

As I was walking away from the sandpit, a man hurried over.

He introduced himself as a talent scout, said that he’d seen me jumping and

would like me to join his athletics club.

To say I was amazed would be an understatement.

I stood there, sand in my shoes, and looked at him.

................................

Then and there I decided that I was definitely going to study English Literature at

Durham University. Probably I would go beyond degree level, I’d take it as far as

I could. And then I’d maybe teach, or lecture…

I had a plan!

From an early age, ‘knowing the plan’ has been very important to me. I am not a

big fan of surprises, preferring to be prepared. In fact, my catch phrase, as my

friends and family often teasingly repeat back to me, is “What’s the plan?!”

Now, as I made the decision about the direction my future would take, it felt good

to know where I was heading.

Or so I thought.

..............................

The Consultant arrived.

He was tall, wore a grey suit and a tie adorned with pink panthers.

I remember telling him that I liked his tie before he proceeded to put me through

the same tests that I’d just completed.

At the end of them, he turned to me and said,

“I’m afraid you’re not going anywhere.

I need to admit you to hospital.

You need a brain scan.

Urgently.”

I was sent straight up to the Acute Admissions Ward where, in a bit of a daze,

Mum and I waited until a bed could be found for me on the correct ward.

As we waited, I noticed the lady in the bed diagonally opposite me turn grey.

And greyer.

And greyer.

Until she died.

Right in front of me.

Curtains were hurriedly pulled round her bed and a few minutes later she was

wheeled away, covered by a sheet.

But I’d seen.

My first experience of being in a hospital ward was one of death.

............

The consultant came to talk some more, the rest of his entourage having melted away. He reassured us as best he could, the pink panthers playing their part as far as I was concerned: they gave me a focus. Then, just as he was leaving, he put a name to the diagnosis. I had a condition called Neurofibromatosis Type 2. Neuro… what? I couldn’t even pronounce it, let alone spell it. And yet I had it.

..........

There was only one option: Surgery. Removal of the tumour on the left side of my brain. They’d remove the largest first, leaving the smaller one, the one on the right, still in my head. For now. The surgeon proceeded to outline what surgery would mean. Possible damage to my facial nerve and of course, as I knew, I would be deaf on the side where they operated. Only I didn’t know. Because no one had told me. Until that day, I never understood what people meant when they said, ‘It was such a shock that the room spun.’

................

[Had Operation]

Then, after three days [in ITU}, came possibly the worst words that any parent could hear, or a surgeon have to deliver: ‘We don’t think your daughter is going to make it; we think she has had a stroke in the brainstem.’ ........My parents looked at each other, facing the loss of their daughter. They were confronted, unwillingly, with a decision that no one should ever have to face: what would they say if asked to turn off life support?

.....................

The machine kept me alive, kept me existing, but I needed needed more than that. I needed to learn to live.

..............

I would not be able to walk the couple of miles there and back as I had done before my hospitalisation. This necessary arrangement highlighted for me that I was not, in fact, returning to full normality. Every day I would watch from the car window as the route I had once walked sped past. Tantalisingly close. Devastatingly distant. It looked the same but I was not walking it any more. I was viewing it through glass.

................

I needed more brain surgery. My barely resurrected return to normality sank back into the ashes.

...............

I was handed a mirror and, despite myself, I took it. I raised it until it was level with my face and forced my eyes to look. And I recoiled. For once the best efforts of my imagination hadn’t prepared me. It was worse than I’d envisaged. The entire left side of my face looked as though it had slipped away from its moorings.....To me, it felt as though I had actually lost my face, not only its movement and feeling. My face was no longer a harmonious whole. It was simply discordant parts – eyes, nose, mouth, cheeks, chin.....This loss of my face resulted in the loss of my confidence.....Inwardly I cried.

...............................

Things had changed so much. Who was I and who was I becoming? I refused to let NF2 define me but I could no longer pretend it was not part of me.

....................

I wasn’t failing. I was not yet fully succeeding. As I struggled with life in general, the difference between ‘failing’ and ‘not yet succeeding’ was crucial. As crucial as acknowledging, again, that success comes in many forms. I was thankful for the lesson learned all those months before, when my mum lifted my chin over a nearly full bowl of Weetabix and said, ‘Well done.’

With my daily eye and balance problems I was no longer able to ignore NF2, so I decided to defy it instead.

.............................................

My ‘hearing time bomb’ was ticking. Belatedly and somewhat futilely, I wanted to attain the potential Marguerite had recognised in me all those years ago. I realised that I’d let my talent lie latent and I was angry with myself for doing so. I’d always assumed I had time. Now, the arrogance of that assumption haunted me. I played under its shadow. Every time. But I still played. Maybe my ear could be so filled with music that there'd be no room for the other tumour to grow?

.............................................

I remember, as clearly as if it were yesterday, one misty autumn day. I was fourteen. Playing hockey. Whack! Someone hit the ball and I began to chase it. Began to run. I reached the ball but something inside made me keep running. Voices called me to stop. Yet still I ran. I was no longer chasing the ball, I was chasing… what? I didn’t know. Chasing my past? Running from my future? All I knew was, I had to keep running. Now, albeit on a cross trainer, I had to keep running.

..................................................

Help me say, “Goodbye.”’

As I listened, little did I know just how soon those words would become more than part of a story I was watching develop on stage. ‘“Wishing I could hear your voice again…”’

Those words would become my story.

....................

‘We have two choices: Either we operate and you lose your hearing or we don’t operate and you lose your life.’ The future I’d been denying was suddenly very present.

..................................

My parents and I walked out of the hospital, trying to absorb news we’d hoped was a long way off. As we stepped outside, the heavens opened and soaked us. Rain.....My gaze travelled unseeingly upwards until, in the grey sky, I saw a rainbow....Despite the grey day, the bad news I’d received, the dread of more brain surgery and a silent future, the rainbows were there. I reached out. And I grabbed them. I still look for rainbows: A smile from a baby, chocolate, a lunch date with a friend, a letter in the post. Anything that brightens my day. I find the rainbows. And I cling on.

..................................

How does one prepare to become deaf? I didn’t know (I still don’t). There were no guide books on the subject. I was lost. Deafness was my destination but I had no map to show me the best route to take.

................................

Soon, I’d no longer hear like me. But I was determined to still sound like me. NF2 had stolen my face and my hearing, I would not allow it to steal my voice, too. I was already different enough.

............................

‘I love you.’ I squeezed their hands one last time and then let go, my eyes stinging as I was wheeled through the doors that led to theatre. ‘I love you.’ Those words were the last I’d ever hear them say. Never again would I hear the voices that had been my supporters, encouragers, companions, defenders and playmates since I was born. ‘I love you.’ The doors swung shut behind me. ‘Wishing I could hear your voice again. Knowing that I never would…’

................................

Finally, I truly appreciated my hearing. All my life I had accepted hearing as just a part of who I was. But part of me had been taken from me. Appreciation came too late. My hearing had gone. Forever. And I didn’t recognise this person whose ears didn’t work. This person surrounded by sound but hearing nothing. Nothing. I was terrified.

..................................

Without my hearing, I felt I had lost control. Not only of what was happening all around me. Of what was happening to me. I was incredibly frustrated......Despite it all, I did begin to make progress, although I had no real idea what this progress meant. No idea whether or not I was ‘doing as expected’.

.............................................

The world whirled around me. Living life. And I found I didn’t want to be part of a reality which was no longer mine

...................................................

No journey can commence without the first step being taken. Each journey is made up of integral parts; some large and some small. My first step to that post office was the start of my journey back into life.

.....................................................

Letting go of hopes and dreams can be hard. Even more so when you have little or no control over why you need to let go. But I discovered that it can also be tremendously liberating. I was eleven years old when I began playing the flute..... I well remember the feeling of amazement and sense of rightness the first time I put a real flute to my lips and blew softly, producing a warbling note.....Though now living silence, each in our different ways, that flute held memories of music once shared. Memories I clung to......I slowly put my flute back into its case, nestling it among the red velvet casing for the last time. From now on, I would listen to the music in my heart. I was ready to let go. I was ready to look forward, To face new challenges.

..........................................................

Dear NF2,

I wish I couldn't write that. I wish I'd never heard of you.......Yes, NF2, I hate you, but I thank you.........I know......there will be more days when I am surrounded by the shipwreck you make of my life.....but I will be clinging to a piece of that shipwreck......Love is Stronger, (Not) Yours, Emily

............................................