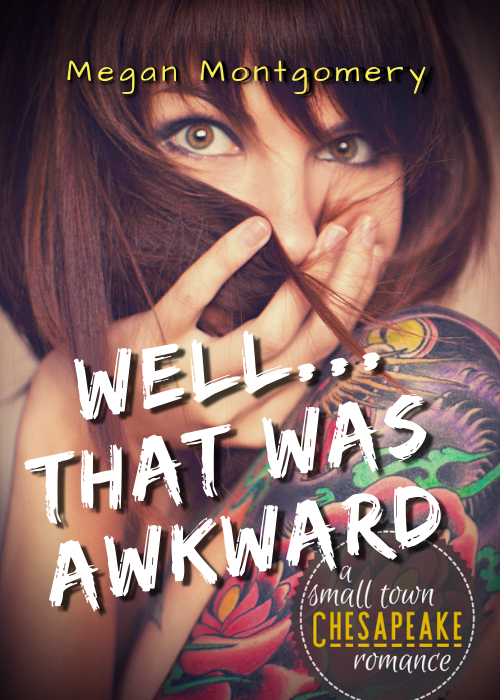

Well...That Was Awkward

I was elbow-deep in vintage cookie cutters and stacks of pink Pyrex casserole dishes when I realized the Three Harpies of the Chesapeake were arguing about me. That is, me as in “the situation in need of remedy.”

My brain throbbed against its confines. If I had to listen to one more comment about my looks, needs, or ought-tos, I was going to close up shop and move somewhere they appreciated outcasts and recluses.

I stood, collecting my dust rag, and heard Mrs. Sylvia Rae Andrews chastise her friend. “I don’t know why you bother, Lorraine. All those tattoos and those clothes with the holes. She’s never going to get a nice man to want her looking like that.” Yep. She was talking about me, alright. No doubt she thought she was whispering, but when deaf old ladies don’t turn their hearing aids on, a whisper becomes a stage voice.

“Hush up, Sylvia Rae,” Lorraine snapped. She needn’t have bothered. I’d heard it all before. In fact, Sylvia Rae repeated her assessment of me nearly every time she came into the shop. I don’t know if it was due to dementia or some latent passive-aggressive tendencies.

I pretended I was completely engrossed in my task of sorting the rolling pins according to size into giant glass jars until they’d moved on to other gossip. When the coast was clear, I quietly resurfaced from my hiding place between a kitchen hutch and a bureau with a rippled maple veneer. I made a mental note to inject some glue between the pieces of wood and clamp it together tonight. It wasn’t too far gone, but nothing was leaving this shop in less than optimal condition. Or as optimal as a two-hundred-year-old piece of wood can be.

I brushed the dust off my hands. I certainly didn’t need to feel guilty for performing covert operations in my own shop. Not if it yielded a necessary repair.

I couldn’t help but listen in again when Lorraine raised her voice, exasperated with her friend. “You can’t expect John to work the high tea fundraiser, Sylvia Rae. It’s nothing but old women like us attending.”

“You’d think he’d volunteer for everything being that he doesn’t have a wife,” Sylvia Rae said. Oh, good. They’d found someone else to marry off. Maybe this poor, wifeless guy would divert their attention away from me and my tattoos.

“Just because he goes to Mass doesn’t mean he’s looking to get married,” Lorraine said.

“Now, Lorraine,” Phyllis jumped in, “You know that I rarely agree with Sylvia Rae, but this time, she’s right. Why else do handsome, single men suddenly start going to Mass every week? And eight o’clock Mass, too? ‘Cause they’re looking to catch themselves a good Catholic girl who’s gonna be a good Catholic wife and raise up some good Catholic babies.”

“I never see you in church, Emerson.” Sylvia Rae turned back around to me. Delightful.

“I’m not looking for a good Catholic boy,” I said, resigning myself to join them as they dispensed their complimentary coffee from the air pot and settled into a Victorian settee in the center of my shop.

“She’s not even Catholic, you idiot.” Lorraine always had my back.

Sylvia Rae didn’t respond and Lorraine automatically repeated, “I said, SHE’S NOT CATHOLIC. Turn your ears on.” Lorraine shouted into her friend’s ear.

“Alright, alright.” Sylvia twisted the tiny device in her ear canal.

“I knew you didn’t hear me ‘cause I got the last word.” Lorraine was almost as grumpy as me this afternoon. Thankfully—or perhaps not—there were no customers in the store.

In an attempt to lure any and everyone off the street to come in and swipe their cards in my store, Blue Heron Antiques in Solomons Island, Maryland, I’d taken to offering free coffee and pastries to my customers. The pastries were things I tried to recreate after dates with my brilliant blue-eyed boyfriend, Paul Hollywood. Okay, my “dates” were technically Netflix binges of The Great British Baking Show during which I pretended to know the correct proportions of a Bakewell tart and drank too many IPAs. And I was alone, except for my mutt, Rousby. But it all yielded some fairly impressive results that brought in:

Precisely. No. Customers.

In fact, my brilliant attempt to ply tourists with deliciousness to boost the store’s business only hindered both my own personal grocery budget and my peace of mind. While the coffee hadn’t exactly attracted customers, it did garner groupies of a different, more octo/nonagenarian distinction, the exact sort that loved to gather daily to gossip about their friends, remark about the placement of vintage luggage stacks on desks, and find potential husbands for single, tattooed, holey-clothed, antiques saleswomen in their early thirties. Too bad only one person around town fit that description.

“You ain’t Catholic?” Mrs. Gordon accused me with a dramatic flair of her eyebrows. Apparently, I had been pulling the wool over her eyes all these years.

“No, ma’am. Presbyterian. But that’s more of a technicality. Dad’s a lapsed Catholic. Mom’s more of a ‘spiritual’ type of person. She floats through religions with the tides, picking up the stuff that sounds like blessings and leaving anything that sounds like work. The worst was when she was Seventh Day Adventist for a few months, and she threw out all my jeans and forced me to wear dresses. The second worst was when she discovered yoga and we had to stop eating bacon.”

Bacon and jeans. That was my religion. I wanted little to do with any other higher power.

“Girl,” Phyllis intoned. “Why do I always see you at the church helping out at the spaghetti dinners and pancake breakfasts—”

“And bingo,” chimed Sylvia Rae.

“I assumed I never saw you at Mass because you went Friday nights,” finished Phyllis.

“It’s good business to help out the community.” I shrugged. “And…they asked.”

Maybe that wasn’t entirely accurate. Maybe I did feel a bit beholden to Our Lady, Star of the Sea, the church that dominated the horizon on the Chesapeake side of the island. After all, I had been raised hearing its bells tolling the hours and almost everyone I knew worshipped there. Maybe I was a sucker for being needed. Maybe a part of me felt robbed of the experience of not having grown up in the parish that was now in my backyard.

Only a small part, though, because still…bacon and jeans.

“I don’t think you’ll do at all for John then,” Sylvia Rae said.

Phyllis and Lorraine both admonished her with “hush” and “keep your mouth shut,” but I knew they were thinking it too. Sylvia Rae was the only one with the guts to say it aloud.

I didn’t even have to know this John to know that they were wrong. Whatever guy who manipulated and groveled his way through church attendance in order to shop for a “good girl” was undoubtedly a misogynist, and the problem wasn’t that I wouldn’t do for him. It’s that he wouldn’t do for me.

At five o’clock on the dot, I threw the lock on the front door and turned off the showroom lamps. I was itching to start the restoration of my newest treasure, an eighteenth-century Queen Anne high boy. Mixing up a batch of wood cleanser, I spread it like frosting on the grimier corners and crevices of the cabinet. While I waited for it to eat into the centuries of grime, I found my favorite metal playlist and cranked up the speakers.

I only worked for an hour or so before I couldn’t look at another brown corner or brass handle in the dim light. The stale air and the fumes worsened my headache, and my legs ached from crouching down in a squat. More importantly, my best bud and furry-coated business partner, Rousby, had been looking at me with sad, sleepy eyes for the past twenty minutes.

Rousby and I raced home. My stomach complained loudly that I’d missed lunch, so after doing all the usual coming home stuff, like the dawdling around, the dropping of the keys somewhere, the kicking off of the shoes, the feeling of panic that the keys had already been lost, the vague look around a disappointingly dull apartment, there was nothing left to do but eat, make more food, and eat that too. I preheated the oven.

I wasn’t one of those cool, cosmopolitan, never-have-any-groceries-in-the-house kind of single girls. I cared way too much about food. I also lived within walking distance from an absurdly awesome grocery store that specialized in foodie delights. We even had a cheesemonger, and yes, Kim and I were on a first name basis. My fridge was always filled with expensive charcuterie, local cheeses, and wild sockeye salmon. Whether or not I ate it before it expired is another tale.

Bacon was something I always had in stock. Not the nitrite-free, uncured, pastured-pork kind, but the good kind—the old-fashioned, name-you-can-spell, artery-clogging, family-pack kind. Rousby and I were a family, right?

I roasted the strips in the oven until they were caramelized and crispy and made myself a BLT. The nutrients in the tomato and lettuce offset the bacon. Probably not the extra mayo though. And definitely not the soft, chewy, lightly-toasted artisanal sourdough.

Rousby took his bacon on a little plate. Neat.

After eating, I geared up for another session of bake-watching with my British mates. I had the ingredients but probably not the time to attempt a whole Victoria sandwich, but I could probably get the genoise knocked out tonight. Then I could have tiny, elegant pastries ready for the weekend, when the shop was busy. Well, busier.

My kitchen was small and newly, albeit beigely, renovated. It had ample counter space to hold my stand mixer, and the cake came together in no time. Cakes were easy.

When the final timer went off, Rousby was crossing his legs to go out. I needed to get out too. The sit-down eating, TV-watching, and baking helped me feel more human and less a slave to anxiety over the ever reddening bottom line of my business, but something about the night air seemed electric, and it called to me. I was suddenly desperate to feel the briny sea sprays of the island air on my cheeks.

As I grabbed a few poop bags from the stash of grocery sacks by the front door, I caught a glimpse of myself in the mirror. It was not good.

My hair was wrapped in my old, stained bandana, and my flannel was now mostly white after a run-in with flour in the KitchenAid. I was an enthusiastic baker, not a neat baker. Alas, just about everyone in Solomons had seen, if not commented, on my choice of apparel, and I was taking the damn dog for a walk anyway. They could all chill if they didn’t like what they saw.

I gave Rousby his privacy to do his business and studied the stars. The night was clear, and the air had a biting cruelty that I relished.

I brought a few bags with me, one for the poop and others for my usual “Save the Chesapeake” thing. I tried to do my small part in protecting the environment and pick up the Styrofoam cups, the empty cigarette packs, the beer bottles and aluminum cans, and the debris collected by the wind that’d settled among the sea grasses and shoreline boulders.

It gave a purpose to my walks, and it was my responsibility to keep my world beautiful. I took a shortcut through the playground and waved to two teenage girls on the swings I recognized from around town. They looked at each other and laughed. Passing the ice cream stand that hadn’t yet opened for the season, I stepped up onto the boardwalk that ran the length of the island from north to south.

Everything was peaceful and right in the world.

The velvet sky wasn’t a mere backdrop for the stars, but the crescent moon—was it waxing or waning? I never remembered the difference—was a sliver of diaphanous perfection. Nights like these, filled to the brim with glistening stars, were the ones that made poets and playwrights look up and see the heavens.

Not a soul was on the boardwalk, though I heard a bar or two of Coltrane when the café door opened across the street and, later, the mad thumping of the bass at the restaurant-turned-club on the next block. The world was alive, and I was right where I was supposed to be, somewhere on the outside, floating around its perimeter.

All my life—or at least since my parents decided to retire and float as far away from me and Blue Heron Antiques as their sailboat could carry them—I’ve been in limbo. Equal parts of me were waiting for something, anything, to happen and feeling not-good-enough for whatever that might be.

Maybe it’s this place that’s filled me with this almost peaceful melancholy. The Solomons Island that I grew up in isn’t the Solomons Island of today. Parts will always be familiar: the land, the jetties where the bay meets the river, the restaurants that specialize in foods fried in old oil. But the oystermen and their skipjacks no longer dominated the coastal vistas of the early mornings. There were far more shopping centers and traffic lights than I ever thought I’d see in this formerly unknown corner of the Earth.

Maybe it’s that this place is for families. And if I was honest with myself, I no longer had one of those. Mom and Dad are only reachable by satellite phone. My brother is probably getting high in a friend’s trailer somewhere. I had seemingly exhausted the dating scene in my county, and my friends had mostly moved away. Some came back, after college and weddings, toting their own young families. I ate their charred hotdogs at their barbeques and dodged the same questions asked of me by the Three Harpies. “When are you going to settle down? Have kids? Be more like us?”

It’s not that I wanted to be like them. I wasn’t exactly bitter or anything. It’s that…oh, Hell…I needed them to see the value of my life as it was.

Except that meant I needed to see it for myself first. Shit.

Somehow, I had reached a comfortable precipice. My choices (and my lack of choice) had been driving me to it. Something had to happen. Something had to shake up my staid life and force me to choose, rather than let me float with the tides. I thought I might have even felt it coming, like a cliff I needed to charge right over, paying no mind to the rocks and the sea beneath.

Then I shook my head and realized my life isn’t a movie and I’m not a lonely, heartbroken character standing on a beach, looking out to sea with a gorgeous woolen wrap swathed about my shoulders.

Oh, wait.

Fuck. Back to reality.

My bags were almost filled with garbage. Why cretins toss their trash out of the car window instead of unloading at the gas station, I’d never understand, but I wasn’t going to let them spoil the atmosphere of my enchanted spring night. Rousby inched closer to the handrail separating the boardwalk from the river that was lapping gently over the algae-coated rocks below. No doubt he caught the scent of an invisible dead fish and wanted to roll around in its perfume.

Before I could press the brake button on the extra-long extendable leash, he was gone. One hundred pounds of dog had disappeared through the railing, down to the rocks and river scum below.

Shit. “Rousby! Come back here.” I jumped forward, tugging on his leash.

It was too late.

His leash was fully extended by now and stuck on a nail between two boards. All the tugging in the world wasn’t putting pressure on his collar.

I reached the edge in only a few steps, but that was all the time it took for a water-loving dog to create disaster. I squeezed through the broken handrail, dislodging and unwrapping the tangled cord on my way down. When I got to him, he was diving nose first, again and again, into what must have been an entire school of putrefying rockfish that lay partially submerged in the mud.

“Ew, Rousby. That’s disgusting.”

He looked at me in shame.

“I don’t care,” I argued with him. The leash was tangled around his legs, and I had to wrap my arms around him to untwist it. “Now I have to give you a bath when we get home.” I smelled my shirt, which had brushed against his red tide-slicked coat. “Blegh. We smell like the Body Farm. You better hope no one’s out for a romantic walk in the moonlight or we’re going to scare them off.”

I struggled to hoist the slimy bastard back up onto the boardwalk and glared into his eyes.

“Don’t you do that again.” His brown eyes looked so pitiful, I rubbed his ears. What was a little more dead fish between friends? I already had to burn my clothes. I laughed at Rousby. Maybe this was the distraction I needed to shake off the nostalgia that threatened to make me feel way too sorry for myself.

I locked his leash so that he couldn’t wander and made our way over toward the bench. Yes, we stunk. Yes, we both needed long baths when we got home, but I wasn’t quite ready to part with such a beautiful night. Besides, we were the only irresponsible ones out this late on a school night. That meant we had free rein to stink it up.

Comments

Fun read

I'm always glad to read something so delightfully written. Great job on this.