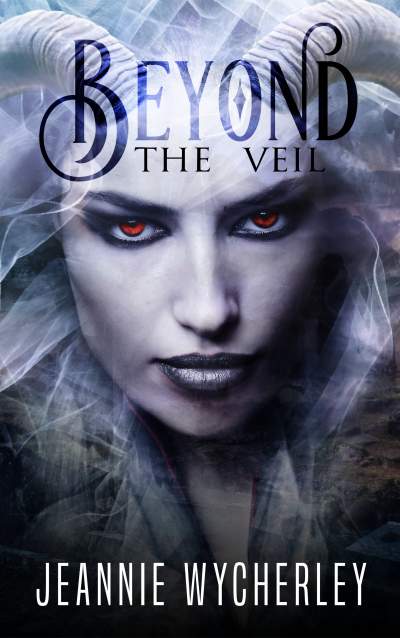

Beyond the Veil

If death were a dance, it would have a catchy rhythm. Two beats per second. One two, one two.

On the other hand, it would be more difficult to dance to the rhythm of births per second. The number of births is equal to four beats every second, and increasing. That’s a little too fast for comfort for most dancers.

But the rhythm of death—one two, one two—that’s a nice, even rhythm. Think about it: one two, one two and another two people have shuffled off this mortal coil. Two people who have drawn their last breath, perhaps after a long illness, lying in bed surrounded by the people who loved them. Dying in comfort, in clean surroundings, with health professionals on hand to ease their passing.

Of course there are those who lie dying in a place in the world where death is brutal. Where medicine is in short supply and clean water is a luxury. Those for whom death is a welcome release.

Wait. That term? Shuffling? You can almost imagine the departed forming a long and orderly queue, can’t you? They’re patient. They’ve had their turn in this world, and now they step beyond the veil, intent on what comes next. They creep forwards, scarcely casting a backward glance at those who weep behind them. What will be, will be. The next stage is a welcome adventure.

As time goes by, the speed at which the queue forms increases. Once upon a time, when the world was relatively young, whole seconds would pass before someone took their place and the queue was easily managed. So what of those who supervise the queue? Fear not, practice makes perfect, and in spite of the quickening pace of population mortality, everyone continues to proceed at a considered rate, precise and sure. Life may be a waiting game, but death is even more so.

To be sure, there are blips. There are occasions when massive surges in the numbers joining the queue slows things down, but rest assured, the veil is always drawn back calmly and quietly, allowing each individual to step through at their own pace. No-one is rushed. However, a deluge of death—a terrorist attack here, a tsunami there, a landslide maybe, or a drone strike—this can cause a backlog, sometimes even a crush. Mistakes happen.

And then there are sudden deaths to factor in. Lonely unexpected deaths. An explosion in the brain, a catastrophic heart attack. A brutal demise at the hands of others. Violent deaths through your own intervention. Mechanical failure. Crushing accidents. Simple misadventure. Human carelessness or negligence. People not looking where they were going.

One two. One two.

So much can happen in one single second.

All of life and death is here.

***

The time is 08.42.07 on the 22nd of May. Heidi Huddlestone is stepping onto a zebra crossing near the Bullring in Birmingham. Her blonde ponytail swings jauntily. She’s due into work by 9, so she has time to grab a coffee. She’s thinking multiple thoughts: slightly concerned about an issue she was having with her graphic design software before she left work on Friday, pondering whether that will impact on her impending deadline this afternoon, while simultaneously marvelling that on this Monday morning in late May, the sky is a brilliant blue and the sun is warm. She’s happy.

As she trots out onto the busy crossing, dodging the oncoming pedestrians, she slips her hand into her cross-body shoulder bag and feels for her purse, hunting for some loose change so she can buy her coffee. She knows there’s a £2 coin hiding somewhere.

At exactly the same moment, 161 miles away, Laura Goodwin is lying in a hospital bed. Her husband Tom is with her. He’s thirsty and wants to grab a cup of tea from the restaurant but doesn’t want to leave his wife. Laura and Tom have been married for forty-one years. She’s fifty-nine years old, and until a suspected mini-stroke the previous evening, they had never spent an evening apart. She has a headache and feels a little spaced out, but that’s to be expected. She’s connected to a variety of machines. They beep endlessly. She’s tired. She looks at her husband and tries to smile. He’s obsessed with tea.

At 8.42.08 Heidi is startled by tyres screaming on tarmac as a vehicle close by accelerates hard. She partially turns. A large black shape flies into her peripheral vision. Someone is shrieking. There is a flash of sickening bright white pain, and she is flying through the air.

Heidi’s head collides with the kerb.

Meanwhile something in Laura’s brain fizzes. Her vision fades to grey, and Tom disappears from her sight. Her husband stands alone, staring at his wife, not comprehending her absence. The machines are beeping, shrill and insistent. A nurse calls for help, and Tom steps back perplexed. Laura has gone.

One two. One two.

***

Out of the blackness flares a tiny speck of light, as though someone has struck a match. The light seems far away. No. Getting closer. Or perhaps it is not so much the light that is closing in as Heidi moving towards it. She is confused about where she is and thinks to stop, but she has the sensation of being drawn by a thread, a gentle but firm tugging, so she has no option but to carry on.

There are others around her. They bustle gently but don’t make contact. Are these people crossing the road with her? Why is it dark? Fear squeezes her insides, and she draws herself rigid, but for some reason she can’t hold on to the feeling. It melts away.

Grey shadows. The dark is less. Heidi ambles forward. With every step she feels lighter, the woes of her life falling away. She sheds her worries the way a snake sheds its skin. She continues on, heading for the light, keeping step with her companions. She has no sense of inhabiting a physical space at first, no walls or a floor, but her steps are even and sure-footed, her balance perfect, her eyesight sharp.

A change. She comes upon a room, actually not much more than a wall. The room is open on three sides, and that emptiness is a void. Black. It stretches to infinity, and yet there is a sense of intimacy. Heidi waits. She will enter the room when it is her turn. She can see that there’s a tall standard lamp to her left; it looks like something her grandmother once owned. It throws a yellow glow, soft and oddly muted, in a six-metre radius. The wall behind it is stained like old parchment, or skin stretched tightly over an African drum. There is a door in the middle of the wall. It is panelled but unpainted, the grain of the wood plainly visible.

Heidi stops. There are many people ahead of her. She is composed. She feels that she has all the time in the world to observe what is unfolding. She stares in fascination at a small woman in a navy dress with a peacock feather design around the hem, plump calves crossed neatly one over the other. She is wearing a deep blue pill box hat that sits jauntily over grey curly hair. Her face is cheery, and her gaze is bright and intelligent. She perches on a plain wooden bench next to the door and taps her knee. Heidi hears the faint scratching of long fingernails against the dark polyester of her skirt with every tap. She appears to be counting out a rhythm. One two. One two.

The people in front of Heidi move steadily forward, and Heidi wonders whether there is not one door but many. The closer she gets to the head of the queue, if she glances sideways, the more doors there appear to be. It’s an optical illusion. The doors open, someone steps through, the doors close. When she concentrates, she can see there is just one door.

Just one middle-aged woman and a much older man are ahead of Heidi now. The man steps forward as the door opens. Heidi spies a curtain, heavy lace, aged the colour of buttermilk. It is lifted from the other side and a wizened hand beckons him through. The curtain is dropped and the door closes.

The woman ahead of Heidi strides forward. The door opens, exposing the curtain, but the rhythm is interrupted. The peacock woman sitting on the bench pauses her tapping and turns her head, her eyes glitter in the soft light. The curtain billows inwards. Until now, all movement has headed sedately one way, forwards to the door, and the atmosphere has been serene.

Now something seems off-kilter.

The middle-aged woman in front of Heidi pauses, uncertain of how to proceed. A dark shadow, perhaps a person without earthly form, flies into the waiting area and collides with her. The woman is pushed back into Heidi, then falls to the floor. For the first time since joining the queue, Heidi has a sense of her physical self as she is joggled. She helps the woman stand. They stare at each other, a brief moment where they each acknowledge the existence of the other, and then the woman pushes past Heidi and dashes away, back along the route they had previously traversed to get to the door.

Heidi is now at the head of the queue. The door opens once more, and there is a flurry of activity. The being that steps through now does so with purpose. Heidi is unsure what she is seeing. A person with a human form, after a fashion, but tall and clad head to toe in the same buttermilk lace that falls into place behind the door. Judging by the shape of the headdress, it has horns, but the lace covers those protuberances and fully obscures its face. Dozens of large black birds fly through the door after her. There is a loud ruckus as they caw and beat at the air and then give chase, following the middle-aged woman as she rapidly departs the way she arrived. The veiled creature’s head rotates, an unearthly movement, stone grinding against stone. It observes the retreating figure as it sprints away and then turns to regard Heidi. Heidi feels the icy grip of terror as its gaze falls on her.

Heidi cannot see a face but senses eyes burning into her own. For the first time since she became aware of her new existence, something akin to fear stirs in the pit of her stomach. She desperately wants to move forward, to step beyond the veiled curtain, into the light beyond, into peace, but this creature – another woman if the long dress is anything to judge her by – is an obstacle that she cannot bypass.

The veiled woman steps towards her and slowly lifts a pale hand. The nails are as black as tar, the tips of her fingers charcoal. Dead flesh. Heidi is repulsed but unable to step backwards, away from the horror, only forwards towards the door. She reluctantly inches towards the woman, who places her hand gently but firmly on Heidi’s chest.

Heidi’s body jolts violently, and she is thrown up into the air, before tumbling back onto the hard ground. Warm air rushes into her lungs in a sudden fury. Until that moment Heidi had been unaware that she was no longer breathing.

Someone, somewhere is counting…

One two…

***

08:45:16

“One and two and three and four and one and two—”

“Wait. I’ve got a pulse. I think I’ve got a pulse. Yes.”

“Is she breathing? Put your ear to her mouth.”

The lycra-clad cyclist is kneeling next to Heidi, holding her wrist, trying to keep track of her pulse. He is desperate to be helpful but shaken by the scene of total devastation all around him. Bodies. A black van. Terrorism. That’s all he can think this is. It’s the current weapon of choice to drive a vehicle into a bunch of pedestrians, isn’t it? There’s blood everywhere. He’s kneeling in it; it’s soaking into his leggings; he can smell it. This poor woman in front of him, crumpled into the kerb, is responsible for some of it. Quite a lot of it.

He does as he’s told. “I think she’s breathing. Yes.”

An off-duty nurse has been administering chest compressions. She sits back on her haunches, exhales, then leans forward to double check Heidi’s breathing again. The cyclist is right. She is breathing. It’s shallow, but she’s alive.

Her black country accent is broad and familiar. “Stay with me, bab,” she says to Heidi. “The ambulances are on their way. You’re going to make it. You’re going to be fine.” She looks up and smiles reassuringly at the cyclist. He’s deathly pale, and she’s frightened he’s going into shock.

“You’ll make it too, champ,” she says, “you’re doing really well.”

Suddenly he wants to weep.

***

09.26.22

Tom stares down at the lifeless body of his wife, his mouth and eyes dry. He can’t take it in. A massive stroke they said, and even here, right in the middle of the hospital, where you might expect them to be able to perform their medical miracles, they hadn’t been able to save her. They had tried – of course they had tried—to resuscitate her for twenty minutes, but the doctor in charge, Tom had forgotten his name already, had called it. Time of death 09.18.00.

He is unsure what to do. They had called him into the room after delivering the bad news. They told him to take all the time he needed.

He puts his hand out hesitantly. He’s a plumber by trade, and he likes to keep fit. For his age, his hands are strong, and his skin is healthy. By contrast, Laura is already looking pale, the rosy hue he associates with her, his long-time love, is fading quickly.

He strokes her forehead and thinks about her brain beneath the skull and wishes his hand could extract the badness, the way an apple peeler can extract a rotten apple core. She is perfect in his eyes and always has been. He can’t bear to think of her any other way.

Her eyelids flutter and he jumps, startled. Fear and incredulity pulse through his body, and he turns for the door, squawking for a nurse. He desperately wants Laura to be alive, but he’s frightened the fluttering is a natural post-death occurrence, like the voiding of bladder and bowels. He opens the door and calls a nurse in. There’s one standing at the nurse’s station making notes. She frowns and idles towards him, clipping the biro to the clipboard she’s marking.

He attempts to explain as she joins him, but his words are confused. Instead he gestures into the room where Laura is lying. When the nurse stops dead in her tracks, Tom careers into the back of her.

Laura is sitting up in bed, her eyes wide open. She observes the nurse and Tom staring at her and appears to find them funny. She giggles. The nurse edges away. “I’d better call the doctor,” she tries to say, but her words are drowned out by the sound of Laura’s increasingly hysterical laughter.

Polly Forster pulled on the handbrake, staring at the house in front of her. She’d been asked to attend the address following a call about a disturbance involving two women and a child. The neighbour, an elderly gentleman, had chosen not to investigate himself and left it to the police. The old-fashioned lace curtain in his front bay window had twitched as Polly pulled up in her marked car, and the light in that room had been extinguished almost immediately. No doubt he hovered behind it, scrutinising her every move.

Back-up was on the way, but it was coming from out of town. Durscombe, being a small town, had limited resources, so Polly elected to proceed by herself. She could never be certain whether time was of the essence in situations such as this. She had to make an informed decision based on her previous experience.

“4286 to control. Attending at 42 Neville Gardens.”

“4286 received. Standing by.”

No 42 was a large 1930s semi-detached redbrick in a good area on the outskirts of Durscombe. The house had a more recent attached garage and a short, winding drive. The front door was closed, and there were lights on in the living room and the front bedroom. Polly climbed out of the Corsa and cocked her head to listen. Everything seemed quiet. Her heart beat a little faster. She had attended dozens of domestic disturbances over the previous ten years or so, and she had yet to arrive at a quiet address. Normally she had to wade in to prevent the perpetrators kicking seven bells of shit out of each other. It was never pretty. But this silence? This was a new one. The hairs prickled to attention on the back of her neck. A quiet house after reports of a disturbance was not a good sign. She smoothed some loose strands of hair away from her face and took a moment to slowly scan the street.

Nothing to see.

As she made her way up the drive, gravel crunched beneath her feet. She skirted a relatively new red Toyota Yaris, in need of a wash, but used in the past few hours, judging by the clean windscreen. She edged close to the bay window and peered into the living room beyond. No net curtains here. The furnishings were crisp, fresh, and modern in soft shades of grey, and the paint on the walls a non-committal cream. There were some children’s toys on a rug in front of a huge TV, tuned to Coronation Street, but there was no-one in the room.

Polly sidestepped to the front door and pressed the doorbell. Not working. She tapped. No reply. She tapped again and tried the handle. Unlocked.