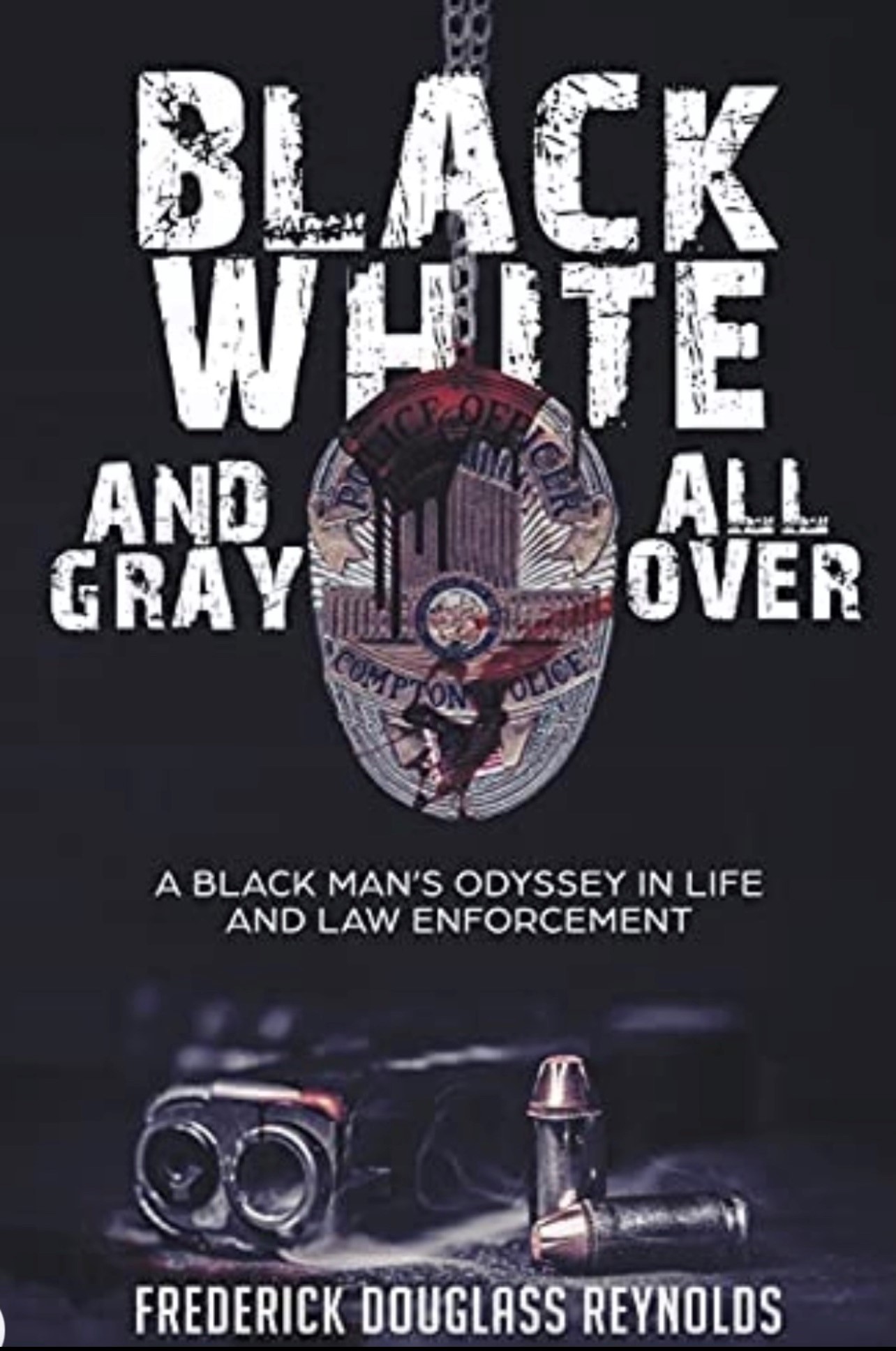

Black, White, and Gray All Over; a Black Man's Odyssey in Life and Law Enforcement

If you want to read their other submissions, please click the links.

Although technically a "cop" book, it reads more like a book about a Black man living in a turbulent America who happens to be a cop. Confronted with racism, poverty, and a dysfunctional upbringing that led to juvenile delinquency, the author was able to overcome these considerable obstacles en route to redemption and reconciliation with himself and what it means to be Black in today's America.

PROLOGUE

THE DAY started off like any other one.

I worked the PM shift, which started at 4:00 p.m. and ended at 1:30 a.m. Slightly hungover, coming off a weekend drink-fest with friends, I took two Excedrin before eating a bachelor's Spartan breakfast of coffee, toast, a slice of cheese, and two boiled eggs. My coffee table doubled as an aquarium. I watched the exotic fish of all colors swim around as I ate, the gentle bubbling sounds helping to hasten the medicine’s effect.

I lived in an upstairs, two-bedroom apartment with a balcony about a mile from downtown Long Beach and six blocks from the Pacific Ocean. Long Beach is just south of Compton, where I worked as a cop. Although the area I lived in was geographically close to Compton, it could not have been more different aesthetically or demographically. At the time, Compton, California, was a predominantly Black city that, although just 10.1 square miles with a population of 90,000, was also an abattoir averaging over 1,500 gunshot victims and eighty murders a year.

After my headache subsided, I went on my usual three-mile morning run on the beach, knifing through the bikini-clad women who were rollerblading under the beautiful California sun. Life was good.

At 3:35 p.m., I got in my burgundy 1991 Acura Legend and sped north on the 710 freeway. I hoped that traffic would not be heavier than usual, but if I was late to work, so what?

I was one of the senior officers on my shift and a field training officer (FTO) as well. The other officers looked up to me, and the supervisors respected me. As a result, I got more than my share of leeway for minor infractions like tardiness. At worst, I would just have to write a “102” memo to the watch commander (W/C) explaining the reason for being late. The memos went into your personnel file for a year, but nobody gave a shit about that. Cops just hate to write in general unless it is an arrest report or filling out an overtime slip.

While Janet Jackson sang, “That’s the Way Love Goes” on the car’s cassette player, my mind drifted to my two kids, Dominic and Haley, who were nine and ten years old, respectively. At thirty-two, I had been divorced for almost four years now, and between the rigors of the job, twice a month weekend visits, and the crap I had to take from their mom, I wasn’t spending much time with them. It is difficult being a cop when you do not live with your kids. When you do, even though you work long and odd hours and sleep a lot, at least you are there. Still, I had to find a way to do a better job as a father.

As I weaved in and out of traffic doing 85 to 90 mph, the twelve-story Compton court building came into view. We called it Fort Compton because we believed it to be the only safe place in the city. In stark contrast to its surroundings, it was an alabaster structure without much architectural imagination standing amidst colorful, single-story homes and overpopulated apartments. A monument dedicated to Martin Luther King Jr. kept silent vigil in its shadow, a beacon of hope and justice in an otherwise lawless land filled with despair. The police station, a two-story building with a basement, indoor shooting range, and a jail with a kitchen for cooking inmate meals, sat next to the Fort. The backlot was behind the station and used for patrol cars and employee parking. Three gas pumps, with a huge marquee atop them with the words, ‘COMPTON POLICE’ in blue letters, separated the booking stalls immediately behind the station and where the patrol and detective cars parked. The dispatch center, a large room without proper ventilation, was next to the entrance to the kitchen for the jail and had a small window on each of two doors. A three-foot retaining wall was the only thing that separated the back lot from passersby walking down the sidewalk.

The backlot was a sacred place for everyone who worked at the station. It was used for everything from private conversations to intimate encounters in vehicles. And “meet me on the backlot,” said in anger was also the precursor for a fistfight between two cops who didn’t necessarily see eye-to-eye on things.

The Heritage House stood behind the back lot and was built in 1869 as a tribute to the city’s founder, Griffith Dickenson Compton. It is the oldest house in Compton and a state landmark. We sometimes went there to drink beer after work. It was a common way for cops to unwind and is known in cop talk as choir practice.

I arrived at work with ten minutes to spare. I walked into the locker room to change, looking for lockers with coat hangers so that I could laugh at the latest fuck-up. Whenever a cop did something stupid or disrespectful, such as a rookie being in the locker room when the senior officers arrived, the other officers on the shift would wrap metal coat hangers around the lock on his locker until the hangers looked like a metal ball. The bigger the ball, the more unwritten rules the officer had broken. If the officer did something particularly egregious, like snitching on a fellow cop or missing a weapon during a search, or he was just an unliked asshole in general, the other officers would also splash liquid whiteout on his locker. There were at least five such lockers in the locker room, harsh reminders of the number of snitches, assholes, and incompetent cops I worked with daily.

A boom-box—confiscated from a street corner when gang members ran off and left it as cops drove up—played in the corner of the locker room. It was blasting “I Will Always Love You,” which was Officer Kevin Burrell’s favorite song at the time. At six foot seven and more than three hundred pounds, he was struggling to put on his bulletproof vest at his locker while trying his best to sing a duet with Whitney. With a personality and charm as large as he was, all the cops loved to ride with him. He had recovered quite nicely from a gunshot wound caused by a fellow officer playing with his gun in the report writing room about a year before. The gun accidentally went off, and the bullet entered Kevin’s left upper thigh as he was writing a report.

Kevin was a star basketball player at Compton High School and a three-year starter at Cal State University Dominguez Hills. Basketball skills ran in his family. One of his older brothers, Clark “Biff” Burrell, led Compton High School to two CIF championships and a sixty-six-game winning streak before the Phoenix Suns drafted him in 1975.

Kevin grew up less than three blocks from the station in the Palmer Blocc Crip gang neighborhood. His mother and father, Edna and Clark, had extended a standing invitation to patrol officers to stop by their house whenever they were hungry. There were sometimes two or three radio cars there at a time, the officers eating barbeque and playing dominoes or spades in the backyard while listening to their radios for calls. After they left, Edna always listened to the police scanner Kevin had bought for her, thrilled whenever she heard his voice.

Kevin had wanted to be a Compton police officer since he was a kid. He certainly earned the position. He paid his dues as an explorer scout at fourteen years old before working as a community service officer and jailer. When the city sent him to the police academy, he caught chickenpox and was unable to complete the training. Undeterred, he self-enrolled in the next academy class. As a testament to how well-liked he was, every officer on the department chipped in to help him pay for the training the second time around. When he graduated, the city hired him as a police officer.

Only the senior cops were still changing when I arrived at work. The rookies were already in the briefing room, which was in the basement next to the men’s locker room. The women’s locker room was small, not much bigger than a walk-in closet, and was on the opposite side of the briefing room. There were never more than four or five female patrol officers on the department at a time, so there was no need for a large locker room for them. As was often the case, no female officers were working that night.

The rookies had to arrive at work at least thirty minutes before their shift began and sit silently in the front row. Speaking out of turn was grounds for a ball of wire on their lockers. They had to stand up on their first day and answer embarrassing sexual questions from the senior officers about their significant others, such as whether she wore underwear, how well she performed fellatio, and whether she would be open to threesomes. Profanity-laden hazing was the norm, even in front of supervisors. After the rookies sat down, they were bombarded with erasers, wads of paper, and even notebooks thrown by the officers sitting behind them. Seating placement was based on seniority, with the most senior officers sitting in the last row. Most of them smoked cigarettes and some held empty soda bottles or cans, which they used to spit their chewing tobacco. The dispatchers sat behind the last row in front of the lunchroom. We called it the Code-7 room because that was the radio code for lunch. The shift briefing started when the supervisors took their seats in front and told one of the dispatchers to close an accordion blind that separated the two rooms.

Lieutenant Danny Sneed was the W/C, and Eric Perrodin was the field sergeant that night. Danny was a middle-aged cop with a short afro and a perpetual scowl occasionally interrupted by a shit-eating grin. Known as the “Plug” because of his short stature and tenacious personality, he was a demanding but compassionate supervisor. Street smart and book smart, Danny grew up in Compton, as did Eric, whose father was a beloved city employee for more than thirty years. Eric’s brother Percy was a captain on the department. He and Eric grew up on Central Avenue in one of the most gang-infested neighborhoods in the city. Percy had long since moved out, and their father had passed on, but Eric and his mother still lived in the same house.

Danny assigned me to lead a team of several Zebra units to address the numerous gang shootings that had plagued the city in recent days. The units were called Zebra in honor of the majestic African animals because they are fearless and fleet of foot and because our patrol cars were black and white at the time. I was training a rookie named Ivan Swanson, a suave, fast-talking lady’s man. Our radio call sign was Zebra-1. Ivan grew up in Carson, a town south of Compton, and his father was John Swanson, a well-respected homicide detective on the department. Lendell Johnson, a muscular cop from Chicago by way of Louisiana, and his trainee were Zebra-2. Lendell was one of my best friends on the department and was a relatively new FTO. I didn’t know much about his trainee, but that wasn’t unusual. Senior officers didn’t pay much attention to trainees. No one gave a shit about them until they got off probation, which was akin to a rite of passage. They weren’t accepted until they had completed their journey. Then, they had to throw an off-probation party and foot the entire bill. The party wasn’t for them. It was for the senior officers who now accepted them into the exclusive club of that thin blue line of law enforcement.

Kevin and James MacDonald were Zebra-3. MacDonald, or Jimmy, as we called him, was a reserve police officer. Reserves were part-time officers who worked for just one dollar a year so they wouldn’t be viewed as doing the job for free. Most people became reserves to try and get their foot in the door to become full-time cops. Others did it just so they could carry a concealed firearm. Jimmy was a young, mild-mannered White guy from Santa Rosa who smiled a lot. His family still lived there where his father, Jim, owned a successful dental implant business, and his mother, Toni, was a homemaker. Jimmy went to Piner High School and played football, baseball, and basketball. He was the quarterback on the football team and was MVP his senior year. Jimmy attended Sacramento State for two years after graduating before transferring to Cal State Long Beach, where he played rugby as he obtained his degree in criminal justice.

Jimmy requested to ride with Kevin that night because it was his second to last shift in Compton before starting his new job as a regular police officer with the San Jose Police Department. He was going closer to home to be near his family. Mark Metcalf and Gary Davis rounded out the team and were Zebra-4. Metcalf, a level-headed White guy in his mid-twenties who grew up in Orange County, was also a reserve. He and Jimmy were best friends, but reserves could only ride with a regular officer or an FTO, so they never rode together. Like Burrell, Sneed, Eric, and Percy Perrodin, Gary Davis was homegrown, and his parents didn’t live far from the Perrodin family. Along with Kevin, Gary was one of the tallest cops on the department. He and Kevin had known each other since they were kids and were teammates on Compton High’s basketball team before Gary went on to star at Cal State Fullerton.

That was the uniqueness of the Compton Police Department. Many of the officers were born and raised in the city or still had family there. These kinds of connections are rare in inner cities, as most of them are policed by cops who have no links to them and view the people who live there with negativity and sometimes outright hostility. Some departments have a residency requirement that applicants live in the city or within a certain distance. The thought process behind this is that cops who have a connection to the community will have more compassion for their citizens. The way Compton cops addressed each other was unique as well. We never called each other by rank. Most of us referred to each other by either surname, first name, nickname, or “dumbass,” “motherfucking,” or “goddamn” before the surname. I was “that goddamn Reynolds” on more occasions than I could count.

The team grabbed a quick bite to eat at Super Marathon Burgers at Compton Boulevard and Santa Fe. The owner was an old Greek guy by the name of Alex. We called him Alex the Greek. He drove an old beige-colored Mercedes Benz which he parked by the walk-up order window. Alex the Greek wasn’t scared of shit. About ten years before, a gangster from the Imperial Courts housing project in Watts tried to rob him at gunpoint. Alex the Greek pulled out a gun instead of money and shot him dead. As the would-be-robber lay on the ground bleeding, Alex the Greek continued to serve customers as they stepped over the dead body to order.

While listening to my fellow officers’ tales of carnal conquests and corny jokes, my mind drifted to thoughts about the woman I was currently dating. Despite my best efforts not to, I had fallen in love and looked forward to seeing her when I got off. In the interim, I joined the rest of the team in eating greasy hamburgers and over-seasoned fries on the hoods of our patrol cars. It never crossed any of our minds that we would pay for meals like this years later, which, when combined with the ebb and flow of adrenaline and stress, would lead to high blood pressure, higher cholesterol, and obesity. But for now, we tried to mask the ever-present tension of policing one of the most dangerous cities in America with bullshit stories and humor. We were all afraid but would never admit it to each other. Still, when you work with someone long enough, you learn to pinpoint the telltale signs of their fear. Some of my peers had a tombstone sense of humor, some an overinflated sense of self, some a braggadocious fearlessness and nervous laughter, and some carried a boot knife, two back-up guns, and the biggest duty weapon allowed. A few were guilty of all the telltales.

The radio blared calls of shots fired and gunshot victims all over the city. Our patrol car sirens screamed in perfect harmony with the ubiquitous sound of the Compton police helicopter, better known as a “ghetto bird.” The regular patrol units received all the report calls, with the Zebra teams responding to help if gangs were involved. At about 8:00 p.m., we were driving on Rosecrans Avenue toward Willowbrook when I heard gunshots in an area called PCP Alley because of the ease it could be bought. A potent hallucinogenic, PCP was known as sherm because users dipped Sherman cigarettes into the PCP before smoking them. It was also called angel dust because in its unrefined state it is a white, crystalline powder and the high has been compared to walking among the clouds. Users often became catatonic or violent and had insane levels of strength when confronted or agitated. We called them dusters or sherm heads. PCP alley was in the area claimed as turf by the Tree-Top Piru Bloods, one of the city’s most violent gangs.

Comments

Author's bio

Frederick Douglass Reynolds is a retired Black LA County Sheriff’s homicide Sergeant. He was born in Rocky Mount, Virginia, and grew up in Detroit, Michigan where he became a petty criminal and was involved in gangs. He joined the US Marine Corps in 1979 to escape the life of crime that he seemed destined for. After a brief stint in Okinawa, Japan, he finished out his military career in southern California and ultimately became a police officer with the Compton police department. He worked there from 1985 until 2000 and then transferred to the sheriff’s department where he worked an additional seventeen years, retiring in 2017 with over seventy-five commendations including a Chief’s Citation, five Chief’s commendations, one Exemplary Service Award, two Distinguished Service Awards, two Distinguished Service Medals, one city of Carson Certificate of Commendation, three City of Compton Certificate of Recognition, one city of Compton Public Service Hero award, one California State Assembly Certificate of Recognition, two State Senate Certificates of Recognition, a County of Los Angeles Certificate of Commendation, one Meritorious Service Award, two City of Compton Employee of the Year Awards, and two California Officer of the Year awards. He lives in Southern California with his wife, Carolyn, and their daughter Lauren and young son, Desmond. They have six other adult children and nine grandchildren.