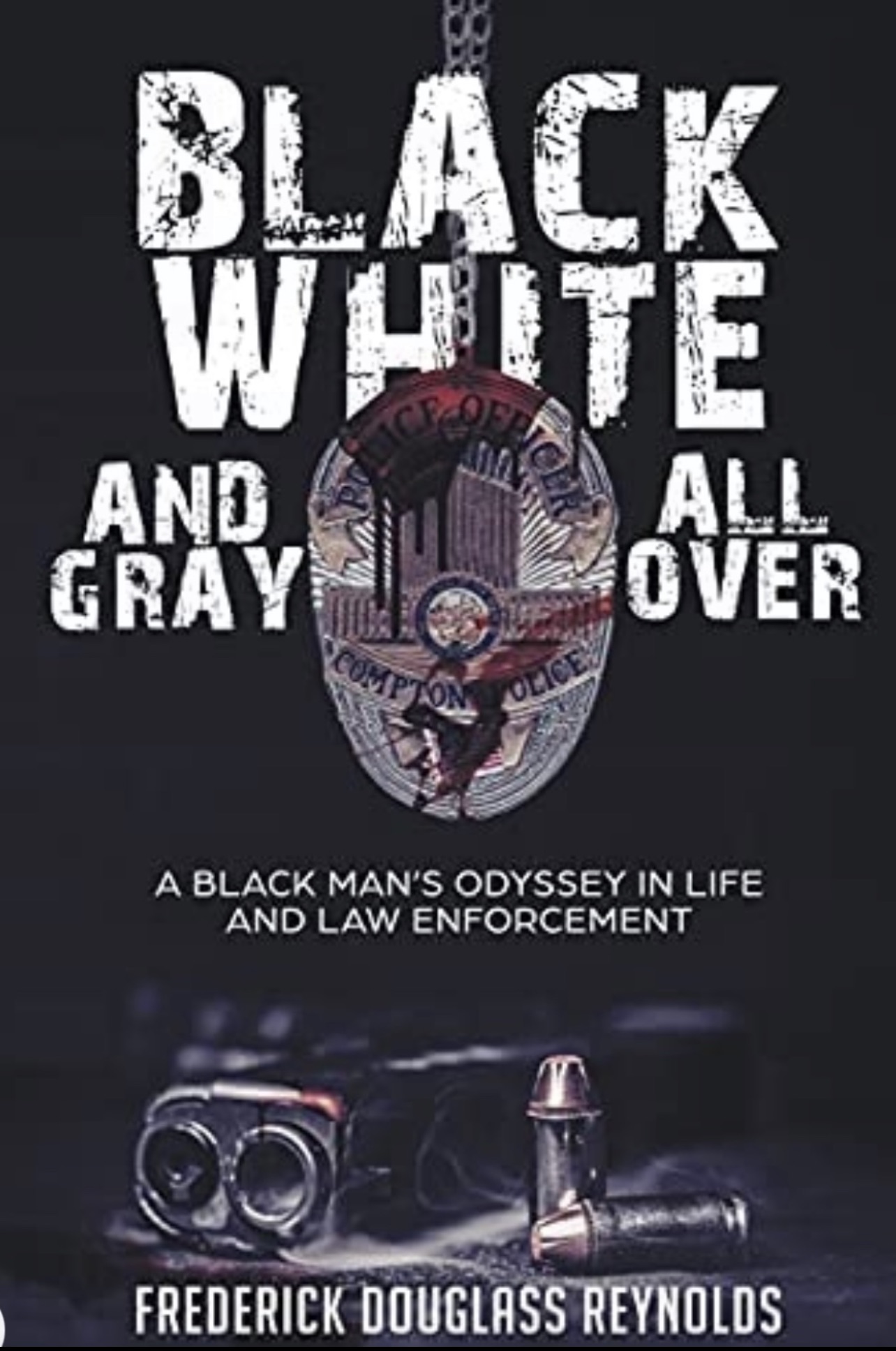

BLACK, WHITE

&

GREY ALL OVER

By Frederick Douglass Reynolds

INTRODUCTION

I was a cop in the city of Compton and some of the worst areas in Los Angeles County for 32 years until I retired on November 5, 2017. I worked for the Compton Police Department for fifteen years and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department for seventeen. It was a turbulent, violent time, to be sure. There were close to 1,000 murders committed in Compton while I worked there, more than by the five Mafia families of New York City combined during that same period. During those 32 years, I never took a life although I could have on at least five different occasions and been justified in the eyes of the law. But the eyes of the law are not the eyes that look back at you from a mirror. I spent over half of my life caring about and risking my life daily for people I did not know and, in some cases, would as soon kill or harm me as easily as taking a breath.

For the last five years of my career, I was a Homicide Detective. I have witnessed the best and the worst of humanity. As I watched some of the most violent people alive become best friends with the revolving doors of the judicial system, I often felt like Sisyphus, pushing an immense boulder up a hill, only to watch it roll back time and time again. Law enforcement is the thin blue line that stands between good and evil, but it also can be a lightning rod for social unrest. The eyes of the world are now on every law-enforcement contact. Peace officers are responsible for the protection of the community and society, but it does not give them ultimate authority. They must be mindful of how they carry out those responsibilities. They must treat everyone with respect, regardless of their lot in life, as they are no better nor any worse than those they are responsible for safeguarding. They must understand that once they pin on that badge, it does not automatically make them the good guy or girl. Badge or not, that title must be earned.

Nor is someone who makes a mistake or commits a crime irredeemable, because the sun shines on the just and the unjust alike. We are all equal in the eyes of the creator. Peace officers must get away from an “us against them” thought process; they must stop having a siege mentality when it comes to policing in specific neighborhoods. If you are a cop and you are so scared that you think every furtive movement or object in the hands of a Black person places you in fear for your safety, find another profession.

This country is fragile. It is like an egg, strong on the outside, weak on the inside. It is a structure built on weak foundations and misery; on the backs and blood, sweat, and tears of millions of people stolen from their homelands. The mighty railroad tracks that helped bridge the east and west laid on the bodies of thousands of Chinese men and women, the land stolen by trickery and violence as the trail of tears cries out for vengeance. All great nations are built in this manner, blood being necessary nourishment for their growth. But sooner or later, the descendants of vanquished or oppressed people will always come knocking. It is just a matter of when.

As a nation, we are in dangerous times. We are standing on the precipice of ruination, divided racially, spiritually, and philosophically. Let us pray that our country heals itself, and that we all find it within ourselves to have love, compassion, and empathy for our neighbors regardless of race, creed, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or political affiliation.

“In a republic that honors the core of democracy --- the greatest amount of power is given to those called Guardians. Only those with the most impeccable character are chosen to bear the responsibility of protecting the democracy.”

-Plato

PROLOGUE

MONDAY, February 22, 1993, started as usual. I was a Compton police officer, living alone in a condominium near Ocean Blvd about a mile from downtown Long Beach and a block from the Pacific Ocean. Long Beach is the next city south of Compton, and although geographically close, the area I lived in could not be farther away aesthetically or demographically. I was working the PM shift; it started at 4:00 pm and ended at 1:30 am. Slightly hungover after the weekend, I took two Excedrin before eating the Spartan breakfast of a single man: coffee, toast, and two boiled eggs. My coffee table doubled as an aquarium. I watched the beautiful, exotic fish of all colors swimming around in it as I ate; the gentle bubbling sounds helping to hasten the effect of the medicine. After my headache subsided, I went on my usual 3-mile morning run on the beach, knifing through the bikini-clad women rollerblading under the beautiful California sun. Life was good.

At about 3:30 pm, I got in my car and sped north on the 710 freeway. I hoped that traffic was not going to be heavier than it usually was in southern California. But even if I was late to work, so what? I was one of the senior officers on my shift and a Field Training Officer. The other officers looked up to me, and the supervisors respected me, and as a result, I got more than my share of idiosyncrasy credit.

While Janet Jackson sang, “That’s the way love goes” on the cassette player, my mind drifted to my two kids, Dominic and Haley. I had been divorced now for almost four years, and between the rigors of the job, twice-a-month weekend visits, and the shit I had to take from their mom, I wasn’t spending much time with them. It’s difficult being a cop when you don’t live with your kids. When you do, even though you work long and odd hours and sleep a lot, at least you’re there. Still, I had to find a way to do better.

As I weaved in and out of traffic doing 85-90 mph, the 12-story court building came into view. We called it Fort Compton because we believed it to be the only safe place in the city. It was in stark contrast to its surroundings, an alabaster structure without much architectural imagination amidst modest homes and overpopulated apartments. A monument to Martin Luther King Jr. stood silent vigil in its shadows, a beacon of hope and justice in an otherwise lawless land filled with despair.

The police station, a two-story building with a basement, jail, and indoor shooting range, sat next to the fort. The rear of the station, or the back lot as we called it, was for patrol cars and employee parking. The Heritage House, a state landmark and the oldest house in Compton, was behind the back lot. It was built in 1869 as a tribute to the founder of the city, Griffith Dickerson Compton, who led a band of wagons filled with families to the area of Stockton, California, just two years earlier. We often used the Heritage House to drink beer and alcohol after we got off work. A common way for cops to unwind is known as choir practice.

I arrived to work with 10 minutes to spare. I walked into the locker room to change, looking for lockers with coat hangers wired through the locks. Whenever a cop did something stupid or if the other officers on the shift just didn’t like him, they wrapped metal coat hangers around the lock on his locker until they looked like a metal ball. The bigger the ball, the more the officer had pissed off the rest of his shift, or the more disliked he was. If the officer did something particularly egregious or was just an asshole in general, they would also splash liquid whiteout on his locker. There were at least five such lockers in the locker room, harsh reminders of the number of assholes I worked with daily.

A boom box confiscated from a street corner when gang members just ran off and left it was in the southeast corner of the locker room. It was blasting, “I will always love you,” Officer Kevin Burrell’s current favorite song. A huge, very likable man, he was at his locker struggling to put on his bulletproof vest while trying his best to sing a duet with Whitney. He had recovered quite nicely from a gunshot wound caused by a fellow officer playing “quick draw” in the report writing room about a year ago to the day. The gun went off accidentally, and the bullet entered Kevin’s upper thigh as he was writing a report. Ironically, the officer who shot him was one of his closest friends.

Kevin was a star basketball player at Compton High school and later a 3-year starter at Cal State Dominguez University. Basketball skills ran in his family. One of his older brothers, Clark “Biff” Burrell, was all CIF when he played at Compton High and was vital to the team winning two CIF championships. He led them to a 66-game winning streak before the Phoenix Suns drafted him in 1975.

Kevin grew up less than three blocks from the station. His mother, Edna, and father, Clark, had extended a standing invitation to patrol officers to stop by their house whenever they were hungry. There were sometimes two or three radio cars there at a time, the officers eating barbeque ribs and playing dominoes or spades in the backyard while listening to their radios for calls. After they left, Edna always listened to the police scanner Kevin had bought for her, thrilled whenever she heard his voice.

Kevin had wanted to be a Compton police officer since he was a kid. He certainly earned the position, paying his dues by starting as an Explorer Scout at 15 years old, before working as a Community Service Officer, Jailer, and finally, Police Officer. He got hurt in the police academy and was unable to complete the training. Undeterred, he self-enrolled in the academy when he recovered. In a testament to how well-liked he was, every officer on the Department chipped in to help him pay for the training the second time around. When he graduated, the city hired him as a police officer.

Only the senior cops were still changing when I arrived to work that day. The rookies were already in the briefing room, which was in the basement next to the men’s locker room. The women’s locker room was small, not much bigger than a broom closet, and was east of the briefing room. There were never more than four or five female patrol officers on the department at a time, and as such, there was no need for a large locker room for them. As was often the case, no female officers were working that night.

The rookies had to be at work at least 30 minutes before their shift began and sit silently in the front row. The most senior officers sat in the last row, some smoking cigarettes, others holding empty soda bottles, which they used to spit their chewing tobacco inside. The dispatchers sat behind the last row in front of the lunchroom. We called it the code-7 room because that was our radio code for lunch. The shift briefing started when the supervisors took their seats in front and told one of the dispatchers to close a collapsible accordion blind that separated the two rooms. The rookies had to stand up on their first day and answer embarrassing sexually infused questions from the senior officers about their significant others. Profanity-laden hazing was the norm.

The supervisors that night were Lieutenant Danny Sneed and Sergeant Eric Perrodin. Danny was a middle-aged cop who wore an afro. He was known as the “Plug” due to his strength and short stature. He was a tough but compassionate supervisor. He was also funny as hell and could have had a successful career as a comedian had he chosen that path. Street smart as well as book smart, he grew up in Compton as did Eric, whose father was a beloved city employee for over 30 years. Eric’s brother Percy was a Captain in the Department. They grew up on Central Avenue in one of the most gang-infested neighborhoods in the city. Percy had long since moved out, and their father had passed on, but Eric and his mother still lived in the house.

That was the uniqueness of the Compton Police Department. Many of the officers were born and raised in the city or still had family there. These kinds of connections are rare in inner cities as most of them are policed by cops who have no links to them at all and view the people who live there with negativity and sometimes outright hostility. Some Departments have a residency requirement, requiring that applicants live in the city or within a certain distance. The thought process behind this is that cops who have a connection to the community will have more compassion for their citizens.

Danny assigned me to lead a small team code-named Zebra to address the numerous gang shootings that had plagued the city in recent days. I was training a rookie named Ivan Swanson. I liked him. He had grown up in Carson and knew how to handle himself. His father was John Swanson, a highly respected Homicide Investigator.

Metcalf and Gary Davis were one of the units assigned to the Zebra team. Metcalf was a reserve officer, a mature level-headed white guy who grew up in adjacent Orange County. Gary, like many Compton cops, was homegrown. He had known Kevin since they were kids and, at six feet, six inches tall, was on Kevin’s basketball team at Compton High before going on to star at Cal State Fullerton.

Kevin rode with James MacDonald that night. They were also part of the Zebra team. MacDonald, or Jimmy, as we called him, was a young white kid from Santa Rosa. Jimmy was very mild-mannered and always wore a smile. His family was much smaller than Kevin’s but just as close. They still lived in Santa Rosa, where his father Jim owned a successful dental implant business, and his mother, Toni, was a homemaker. Jimmy only had one sibling, an older brother by the name of Jon. Jimmy went to Piner High School and played baseball, and basketball, and was the quarterback on the football team where he was MVP his senior year. After graduating, he attended Sacramento State for two years before transferring to Cal State Long Beach, playing Rugby as he sought his degree in Criminal Justice.

Jimmy was also a reserve officer and Metcalf’s best friend. He had just got hired as a full-time officer with the Santa Rosa Police Department. He asked to ride with Kevin that night because it was his second to last shift in Compton. Everyone loved riding with Kevin because of his general affability and good nature. Reserve officers weren’t allowed to ride together and could only ride with senior officers or FTO’s. I had never ridden with Jimmy and looked forward to having the honor of riding with him on his final shift in Compton the following night.

The rest of the team consisted of Lendell Johnson, a muscular cop from Chicago by way of Louisiana, and his trainee at the time, Duane Johnson, no relation. We all grabbed a quick bite to eat at Louis Burgers on Compton Blvd, eating ghetto hamburgers and French fries while drinking stale ass coffee on the hoods of our patrol cars. As we laughed and told jokes, trying to mask the ever-present tension of policing one of the most dangerous cities in America, my mind drifted, thinking about the girl I was currently dating. Despite my best efforts not to, I had fallen in love with her.

After eating, we drove through the city, chasing gang members off corners whenever we saw them congregating. It was a busy night. The radio blared calls of shots fired and gunshot victims all over the city. The screaming of our sirens was in perfect harmony with the ubiquitous sound of the Compton police helicopter, better known as a Ghetto Bird. The regular patrol units got all the report calls, with the Zebra team responding to help and obtain information if gangs were involved.

At about 8:00 pm, the team was driving on Rosecrans towards Willowbrook when I heard gunshots coming from an area known as PCP alley due to the amount of the drug sold there. A potent hallucinogenic, it was also known as Angel Dust or Sherm. Users often became catatonic or extraordinarily violent and had insane levels of strength when confronted or agitated. We called them dusters.

The rest of the Zebra team followed Ivan and me to the sound of the gunshots where we saw a guy standing next to the driver’s door of a Cadillac. He was shooting toward the alley with a shiny semi-automatic pistol. I pulled behind his car, and Ivan and I got out, guns in hand. “Compton police, muthafucka! Drop the gun!” These are the career-defining moments in the life of a police officer both emotionally and psychologically. Yes, we could have shot him. But we couldn’t see who or what he was shooting at, and he posed no direct threat to us at that point.

If he had turned towards us, we would have put him down. But he didn’t, so we didn’t. He dropped his gun and put his hands high above his head as he screamed at us not to shoot. Ivan handcuffed him and put him in our backseat while I told Kevin and Jimmy to check the alleyway for victims. They were unable to locate anyone or any signs of blood, just multiple bullet holes in a wooden fence, so Lendell and his trainee took the shooter back to the station to book him and write the report. Afterward, the city got quiet.

There was hardly any radio traffic and no calls for service. Not entirely unusual for a weeknight, but most of the time, it didn’t get this quiet until well after midnight. Metcalf, Kevin, Gary, and Jimmy decided to take code-7 at a Sizzler’s restaurant in Long Beach, but I decided to take advantage of the lull in violence to get off early and see my girlfriend.

At about 11:00 pm, I went out to the back lot to get some fresh air while Ivan caught up on our reports. I went back into the station when it started to drizzle. After bullshitting with Lendell for a few minutes, I told Ivan to unload our car while I went to the locker room to change. I had just unlocked my locker when I heard the dispatcher over the station intercom. “Compton Officers, we’re getting reports of an officer down at Rosecrans and Wilmington. Unit to respond code-3, identify?”

I froze. I had been a police officer since 1986 and had never heard an officer down call before. I slammed my locker shut and ran up the stairs. Ivan and I sped out of the backlot, our overhead emergency lights activated, and siren screaming. In my rear-view mirror, I noticed that Lendell and his trainee were behind us. The dispatcher updated the call just as we got to Compton Blvd, her voice frantic. “Compton Officers, we’re now getting reports of two officers down! Two officers down, Rosecrans and Wilmington!” And with a sense of foreboding, I knew the officers were Kevin and Jimmy. What I didn’t know was what I would see when I got there, nor would I realize the cross I would have to bear unjustly for years to come.

CHAPTER ONE

MY parents Charles Delton and Theresa E. (Kirby) Reynolds were born near rural Rocky Mount, Virginia, about 300 miles from Annapolis, Maryland. The Lord of Ligonier, an 18th Century slave ship built in London, sailed from the Ivory Coast of Africa across the Atlantic Ocean and through the Chesapeake Bay, where it unloaded slaves in Annapolis in 1767. It is the only recorded voyage in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade database for this vessel, which could carry 170 slaves packed sideways but only 140 if they lay on their backs.

Only 98 of the 140 who made the trip survived. One of the slaves was Kunta Kinte, a direct descendant of Alex Haley, the famed author of the novel “Roots.” Doctor William Waller bought him. Waller and John Reynolds, who also bought slaves from the Lord of Ligonier, were Virginia plantation owners from Spotsylvania County, which is about 180 miles from Rocky Mount. It is not a stretch to believe that one of my ancestors may have been on the ship, too, as slaves often took the surnames of their masters. This possibility is supported by a passage from a book written by one of the greatest Americans of all:

“The whisper that my master was my father, may or may not be true; and, true or false, it is of but little consequence to my purpose whilst remains, in all its glaring odiousness, that slaveholders have ordained, and by law established, that the children of slave women shall in all cases follow the condition of their mothers; and this is done too obviously to administer to their own lusts and make a gratification of their wicked desires profitable as well as pleasurable; for by this cunning arrangement, the slaveholder, in cases not a few, sustains to his slaves the double relation of master and father.”

----Frederick Douglass----

My father was an alcoholic. He and my mother grew up in Rocky Mount, both products of large families. My father had six brothers and three sisters. His family was sharecroppers. They grew up in a white two-story house with circular pillars on either end of an expansive porch that evoked images of ancient Rome. The pillars supported the upstairs balcony where my grandparents would sit and watch the sunset on the sprawling land that wasn’t theirs; land owned by Doctor FB Wolfe, a wealthy white doctor from one of the most prominent families in Virginia. The Wolfe family were former confederates and later experienced a high level of success in business and various vocations. Many of them practiced and taught medicine and law.

My mother had five brothers and one sister. In a twist of irony, her family farmed the product with which the name RJ Reynolds has become synonymous; tobacco, while my father’s family, whose descendants may very well have been owned by him, toiled in hay fields. The house my father grew up in looked like a plantation house. I don’t doubt that slave owners once lived in it. Many sharecroppers were former slaves. Once freed, they had no place to live or any means of making money, so they farmed the land in exchange for housing and a share of the crops produced. Thus, sharecropping, much like welfare over a hundred years later, became generational.

My mother’s family owned their house and land. The house was a small, one-story structure with a large basement on at least 40 acres with a stable of hogs, roaming chickens, grazing cows, and at least one mule. The family cemetery, filled with ancestors going back as far as the early 1800s, was about 75 yards from the house. Some of the headstones only had a name and date of death etched in the stone; a few only had a first name and year of death.

My father dropped out of school in the sixth grade to help farm the land where his family lived. During later years, he would occasionally help his Uncle James “Bus” Nimmo transport bootleg liquor in vehicles, known as running shine. Uncle Bus earned his nickname because he had the strength of three men, especially when he had been drinking. He got arrested once and broke his handcuffs before being beaten unconscious by six deputies.

My mother’s family sent her to live with her paternal aunt and uncle in Detroit as a young teenager. She got pregnant at 15 years old while attending Northwestern High school, and her aunt sent her back to Rocky Mount. The stigma of an unwed pregnancy was unacceptable during that time, leading to my mother giving birth in her bedroom to a baby girl named Linda Faye in August 1957. No one in Rocky Mount knew the shame of Linda being born out of wedlock. To the good folk of this quaint little town, she was my mother’s baby sister, the last of eight children born to my maternal grandparents.

Less than a year later, my mother got pregnant by my father. They were married on December 24, 1958, in an apparent shotgun wedding as my brother David was born just two weeks later, delivered by Doctor Wolfe. My parents moved into a one-room wooden shack about 100 feet behind the white house. There was a potbellied stove in the center of the room for cooking and heat in the winter. As there was no way that anyone related to the original occupants of the white house would have lived in a structure such as this, it was most assuredly quarters at one time for slaves or newly freed ones with nowhere else to go. And here, on the site of generations of despair and racial inequality, is where I was conceived.

I was born at Franklin County Hospital on November 5, 1961. My birth certificate shows my father’s occupation as a farmer and my mother’s as a housewife, our races listed as “N.” Doctor Wolfe delivered me as well. It was a difficult birth for my mother; I was a breech baby. A high-risk delivery, frequently the baby dies. Sometimes the mother dies as well. The older women in Rocky Mount believed that breech babies who lived were old souls who came into the world ready to run. This belief is apparent in my given name. While most children born during this era were named after biblical figures, I was named Fredrick Douglas after Black Abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

My genealogy shows that I am Nigerian and Cameroonian with mixtures of Benin, Togo, and Mali. It is no surprise that I have English (Wales), Irish, and Scottish blood as well; there are no true descendants of Africans forced into slavery in the Americas who do not have any Caucasian blood in them. Both William Waller and John Reynolds were of Irish and English descent.

I am sure that my mother, having had a taste of the big city, longed to return there. Detroit was home to the automotive industry. A multitude of Blacks migrated there in search of better lives, a trenchant contrast to the forced diaspora of their ancestor's role in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. Perhaps sensing my mother’s wistfulness for the city or more likely a result of her insistence, my father joined this migration, driving us there in 1962 with the Green Book, a Black traveler’s guide to Jim Crow America, nestled securely in the glove box. Ford Motor Company hired him the following year.

We lived in at least five different apartments during the early years. They were all in squalid conditions; roaches ruled the roost even after the lights came on. Several of them had rats, some as big as small cats. One of them bit my mother on the nose while she was sleeping in bed one night. When I was just shy of five years old, I put the stopper in the tub and turned on the water to take a bath. I walked out, and about five seconds later, I heard horrible screeching and scratching sounds coming from the bathroom. A cat-sized black rat was in the tub, struggling to climb out. It had come through the faucet. Instead of calling for my mother or father, I grabbed the box for my favorite toy, a View-master stereoscope, placed it on top of the rat, and drowned it. To this day, from time to time, I still have nightmares of screaming rats.

The apartments we lived in were all in one general area of the city, close to my mother’s aunt and uncle’s house. We visited them all the time. I hated going there. Her uncle was a cruel man, condescending to David and me, and he taunted us incessantly. My mother’s aunt and uncle hardly ever talked to each other. They would never sleep together again after my mother left their home in 1956, sleeping in different rooms with my mother’s aunt locking her bedroom door at night.

My youngest brother Derrick was born in November of 1965. We were living on the second floor of a two-story, two-family flat at the time. It was next to a liquor store and about two blocks behind the Olympia Stadium on Grand River, where the Detroit Red Wings played hockey. Derrick was much darker than David and me. I would frequently ask my mother why which angered her to no end, sometimes prompting replies of “shut up boy,” and other times slaps to my head. The demon that is alcohol would grow to haunt my father around this time. Perhaps it grew out of a seed planted years earlier by Uncle Bus that strength can come from the bottle, some traumatic, uneven circle of life event providing it with fertile ground.

My father was sad or drunk all the time. He hid liquor bottles all over the house, even under my mattress when I was as young as four years old. My mother poured them into the toilet whenever she found them as he watched, pleading with her not to. Despite this, he never argued with her or hit her. Instead, sometimes when he got paid, he wouldn’t come home for two or three days. When he did come back, smelling of cheap perfume and even cheaper whiskey, my mother cursed him out and made him sleep on the couch.

A few times, my father came home on foot or in a cab after crashing one of our family cars. Other times he didn’t make it back; he was arrested at least three times for DUI. In retrospect, I understand why he sometimes wouldn’t come home. But I also know why he always came back. He loved his boys—all of us. Although my mother clearly showed favoritism toward Derrick, my father treated us all the same. Sometimes he would take the whole family to Windsor, Canada, just to get ice cream, telling us it was so good they had to make it in another country. And I believed him, too, the taste of the ice cream sweetened by the fact that during the trips my parents hardly argued the entire time. It never lasted past the next day, though.

The summer of 1967 was sweltering. Martha Reeves and the Vandellas’s seminal hit Jimmy Mack dominated the airwaves. My father was a huge Detroit Tiger fan and often took David and me to games at Old Tiger Stadium. Originally named after owner Frank Navin, it was built in 1911 at the corner of Michigan Avenue and Trumbull in Corktown, the oldest neighborhood in the city. The stadium screamed tradition, an iconic ballpark on the order of Yankee Stadium and Fenway Park. Nancy Whiskey Pub was just a few blocks away on Harrison Street and had stood there since the turn of the 19th Century when it was known as Digby’s saloon. Legendary ballplayers like Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth drank there during prohibition, lusting after adoring women after games while members of the infamous Purple Gang held court.

Local 299, home of powerful Teamsters boss James Riddle Hoffa, was just down the street on Trumbull Avenue. The local was within a few miles of the Detroit River, where many victims of the Purple gang and no doubt associates of Hoffa’s as well found their final resting places. Cobblestone Streets added to the traditional feel of the area, harkening back to a time when trolley cars rolled down the street filled with well-dressed passengers smoking cigarettes and reading the Detroit Free Press.

My father owned a red convertible Ford Galaxy 500. He always parked at least half a mile away from the ballpark so he would have extra money for food and a program. The people who lived in Corktown were tough. Originally from County Cork, Ireland, their forefathers had settled there in the 1840s after fleeing the Great Irish Potato Famine. Although at the time, the Irish were not generally fans of Blacks, they never bothered us.

On Sunday, July 23, the Tigers played the New York Yankees in a doubleheader. My father took David and me to the first game. I saw smoke rising in the far-off distance as we drove to the stadium but didn’t pay much attention to it. Braving the wooden splinters from the $1.00 bleacher seats in right field, we watched Yankee Centerfielder Joe Pepitone hit a 2-run homer off Mickey Lolich and power his team to a 4-2 victory. The Tigers got even in the second game, as Willie Horton, a young Black outfielder and one of the most popular players on the team, hit a home run to lead his team to victory.

Instead of going home after the game, Horton, still in uniform, drove to 12th Street and Clairmont, where he had a newspaper route as a little boy. The smoke I had seen was the result of rioting, which started at 3:30 am at a Blind Pig at that same corner. Horton was a hometown hero and was dearly loved in the Black community. He stood on the hood of his car and pleaded with rioters to stop destroying their neighborhood. Instead, they politely told him to go home, so he didn’t get hurt. Two days later, his teammate Mickey Lolich would be protecting the city with the Michigan National Guard while Horton and the Tigers were on the way to Maryland to play the Baltimore Orioles.

The racial turmoil in Detroit was palpable in the 60s. The city was 40% Black while the police force was 95% white. The police were deployed disproportionately in areas where Blacks lived, so I rarely saw an officer who looked like me. The Civil Rights movement was in full effect; Martin was calling for equality through peaceful means, and Malcolm was demanding it by any means necessary. Large numbers of Black men were being drafted to fight in the Vietnam War and sent to where the heaviest fighting was taking place. It had been unbearably hot all summer, especially during nighttime hours, and July 23 was certainly no different. The blind pig incident was a perfect storm. Two Black servicemen who had just returned from Vietnam were there celebrating. When cops tried to arrest several patrons, the tinder box of years of pent-up frustration at mistreatment and abuse at the hands of the police coupled with the heat, exploded.

Corktown was serene as we walked to our car after the game, but I could feel the tension in the air. My father let the top down, and hot, humid air clung to my face; the smell of smoke from burning cars and buildings assailed my nostrils as we approached Grand River. I saw dozens of Black men and women running in the streets carrying TVs, stereos, and food. Several of them were going in and out of dry cleaners, arms filled with plastic-covered clothing.

Looters were emptying the corner store when we got home. I felt sorry for the owners, a kindly Jewish couple who had wisely chosen to return to the suburbs at the first onset of trouble. My mother was watching the city-wide destruction and looting on our little black and white TV, the same one that she watched John-John Kennedy salute his father’s casket in 1963. Later, I looked out of our living room window towards the Olympia Stadium, watching the glow of fires and flashing lights of emergency vehicles while listening to the blare of sirens for hours.

The next day, President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered the deployment of National Guardsmen and the US Army. Tanks, flanked by uniformed troops carrying rifles with fixed bayonets, were soon rolling down the streets. When one turned down ours that night, I was curious and wanted to see it. The tank stopped when I pulled the curtain back, and soldiers yelled and pointed at me as the gun turret slowly turned toward the window. My father pulled me to the floor and laid on top of me with a forefinger to his lips. After what seemed like an eternity, the tank and troop formation continued patrolling.

The following night, the infamous Algiers Motel Incident occurred about one mile from the flashpoint of the riots. Detroit cops killed three Black male teenagers. One of the cops had already killed two Black men since the start of the rioting. His name was David Senak. Fittingly, his fellow officers called him “snake.” The cops and National Guardsmen had gone to the motel because of reports of a sniper. They went inside after seeing people in a window. The incident spiraled out of control when they discovered white women hanging out with the three teenagers and four other Black men.

The shedding of my innocence started in earnest on that sweltering day in July. It was a precursor to an upbringing that would be a dichotomy of emotions, a roller coaster of physical and emotional abuse with a sprinkling of joy. Dickens could very well have been writing about my childhood and hometown as Detroit was indeed a Tale of Two Cities. There were the areas where Blacks toiled and struggled, lived in sub-par housing, and got policed incessantly. And then there were the affluent areas where the residents lived blissfully, ignorant of the cesspool just a stone’s throw from their manicured lawns and automatic sprinkler systems.

By 1972, my mother was working at the Michigan Consolidated Gas Company. Her income, combined with my father’s, allowed them to buy a two-story brick house with a basement and detached garage. In later years, I would be privy to family rumors from the Kirby side that my mother’s vile uncle gave her the down payment for the house, which was on Whitcomb Street on the northwest side of the city. We were the third Black family on the block. We had joined the group of Detroiters oblivious to the nearby cesspool. Within three years, the only white people left would be an elderly couple who lived next door.

Our new house, once owned by Detroit Tiger pitcher Milt Pappas, had a large, grey metal gravity furnace in the middle of the basement. Commonly called an Octopus furnace, it had long ducts coming from the central unit that fed into different rooms and a small door on the front that looked like a mouth. The furnace made a loud “whoosh” like the roar of a monster whenever it came on. There were two rooms in the basement. One of them housed the grey monster. The other room was at the base of the stairs and contained a couch, a love seat, a TV, an eight-track cassette player, and an amplifier for my father’s guitar. The rigors and monotony of using his hands to put rear-view mirrors on Mustangs at the River Rouge plant in Dearborn didn’t affect his ability to play the guitar at all. Drunk most of the time and trapped in a menagerie of misery, he would sit on the couch playing it while listening to Bobby Blue Bland lament about Stormy Monday Blues no matter what day of the week it was.

My father was a great singer and guitar player. Before he married my mother, he was part of a legendary group in the Rocky Mount area called the Starlight Gospel Singers. They were like rock stars with no shortage of big-legged church groupies following them from church to church. Undoubtedly, my father had his share of them; he was a very handsome man. I am sure that as he sat on the couch playing his guitar and singing, he reminisced about days gone by and things that might have been.

My family went to Rocky Mount to visit my grandparents every summer. We always stopped at my maternal grandparent’s house first. My grandmother was very mean, particularly to my mother, Linda, and Derrick. She once held Linda’s thumbs to a hot stove to try and discourage her from sucking them, and she shamelessly treated Derrick as an outsider. She always spoke to my mother, dismissively, whenever my mother tried to have a conversation with her. After a few obligatory hours at the house, we would leave Derrick there where he had to work in the tobacco fields, topping and priming in family purgatory. When I once asked why he had to stay, my mother told me to shut up and not worry about it as my father remained curiously silent.

Small, modest homes with cows grazing behind barbed wire fences periodically came into view as we drove away. The rustic atmosphere of the area was refreshing, a pleasant contrast to the concrete jungle I called home. We always stopped at a local store to get Dr. Pepper soda before getting to my paternal grandparents’ house. The owner of the store was the leader of the local KKK chapter. Beforehand, no doubt, with the fate of Emmitt Till heavy on his mind, without fail, my father would instruct us not to look at any white women and to address the men as sir if they spoke to us. With most of my father’s life overshadowed by the wings of Jim Crow, he most assuredly knew that the trees in Rocky Mount had borne strange fruit on more than one occasion for far lesser transgressions.

I loved visiting my paternal grandparents. Their house was in the mountains at the end of a long, winding dirt road about a mile from Route 220, a major highway. There was a metal gate halfway to the house. It was there to keep livestock from wandering down onto 220. Either David or I would have to open the gate and wait to close it after my father drove through. We would then reach out the car window and pick blackberries from the bushes that bordered each side of the roadway as we continued to the house. The odor of freshly cut grass and patties deposited by the old black bull stalking the confines of a nearby bullpen was always heavy in the air and intoxicating. Fallen apples were plentiful, never far from the trees that bore them. I loved it most when it rained; the petrichor from the grass created a patchwork quilt of aroma.

No less than a dozen family members were on the porch heralding our arrival, some standing, others sitting on the multi-person swings on each side of the porch. There was no arguing while we visited, and it wasn’t an act; they were just genuine people. They laughed heartily and treated each other with respect and reverence.

My paternal grandfather, just one generation removed from slavery, was named Walter Lee Reynolds. He was a short, dark-skinned man who wore bib overalls every day. On Sundays, he would dress them up with a white button-down shirt, and a pork pie hat. He never went to school but had the sagacity of a man who had seen the worst of humanity and who knew the strength of family. Grandpa Reynolds didn’t talk much, but when he did, everyone immediately shut up and listened, patiently waiting for whatever wisdom to flow from his mouth.

My paternal grandmother’s name was Mary. Affectionately known as Mom Mary, she was a singular, six-foot-tall coca-skinned woman. She had straight black hair that at times touched the hem of her ubiquitous knee-length flower-print cotton dress. The stoop in her back was the only clue that she had given natural childbirth to ten children, the last one just before the onset of menopause.

My father’s three sisters were Arlene, Shirley, and the baby of the family, Emma, who was born with Down syndrome. After my grandparents died, Shirley, in unbelievable selflessness, would dedicate her life to providing for Emma, never marrying or having children of her own. Emma’s face always lit up whenever she saw me, as she said the same thing every time: “That’s my nephew Fred. Fred like biscuits and gravy.” And I did too, sopping up as much brown gravy with as many homemade biscuits as my mom Mary put in front of me.

As good as the family atmosphere was at my paternal grandparents’ house, the atmosphere at my maternal grandparents was just as bad. Something just wasn’t right there, and I could feel it even at such a young age. I always felt as if I opened the wrong closet door, I would get smothered by the skeletons that fell out. Just maybe, the long-denied denouement as to why my mother got sent to Detroit in the first place would be among them.

I was devastated every time I had to go back to Detroit. Starting around the time Derrick was born, rarely do I recall peace or tranquility in our house. It was difficult being there; I struggled to find solace or sanctuary from the turmoil but did the best I could as I would sometimes hide in a closet and read by candlelight. I was smart and a voracious reader who, according to my mother and thanks to Arlene and Shirley, had learned to read by the time I was three years old. When I was six, I read the “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.” Realizing that my name was spelled differently, I began spelling my name like his. I also discovered that I had an innate talent for drawing, often rendering artwork worthy of framing before I was ten years old.

I whizzed through elementary and middle school and was promoted from the 6th grade to the 8th grade. I started Thomas M. Cooley High school at 12 years old. It was difficult as I struggled to fit in, and was teased, and bullied because of my age. I went from turmoil at home to ridicule at school daily. I made friends with two other kids in the neighborhood, Butcher, and Keith, who collected Marvel comics and tried to draw. Because I was such a good artist, we bonded right away. I started reading comic books to escape reality, finding a corner in the basement away from the gray monster in a vain attempt to drown out the chaos when the closet was unavailable. Butcher and Keith lived in peaceful homes with functional family structures. Sometimes I would go to their houses where we read comics and drew superheroes late into the evening until their parents made me leave. I should have continued to hang out with them. But my life was destined to take a darker path.

Comments

Wonderful start

I love how frank you are about it yet still show emotion.