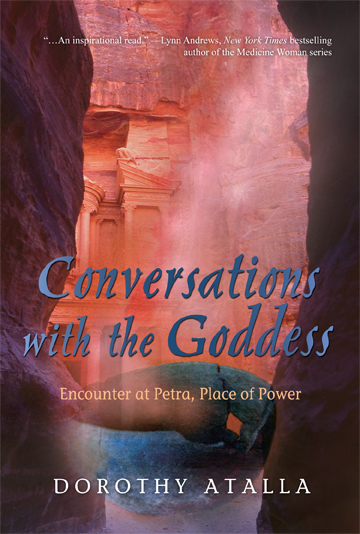

Conversations with the Goddess: Encounter at Petra, Place of Power

Prologue

In these pages I will share with you my encounter with the Goddess. Yes – the Goddess.

I had learned that goddesses were relics, products of ancient peoples‟ mythic imaginations. We of the modern world, on the other hand, are beneficiaries of the evolution of thought lifting us from the murky swamp of old world-views. That‟s what I used to firmly believe. Until I met up with Her in a most unusual place. Imagine traveling to the ruins of a site where the imprint of a long-vanished civilization leaves an indelible mark on you. I traveled to such a site in Jordan, a country littered with archaeological ruins from many eras. One of the most memorable experiences of my life was my visit to the ruins of Petra, a Nabataean Arab city carved out of the rock of the Biblical mountains of Moab.

But the biggest surprise from my visit to Petra was this: my journey was not over when I returned home. I just didn‟t realize it for a while, for seven years, in fact. I didn‟t know that my journey to Petra would lead me into an inner journey which would transform my life, or rather, I should say transform my perceptions about it.

You see, the Great Goddess has her own powerful way of attracting your attention. By following my curiosity about her, I found myself taking a step into uncharted inner ground, every bit as amazing as the site of Petra. I didn‟t know at first that my curiosity would lead me back into the thicket of my own confusions, and then through it to something new, as I asked questions all along the way.

I asked questions – and I was answered. All of which became a lengthy dialogue that is the main part of this book.

My inner journey began after I started meditating in 1980. I was pleased to advance in meditation to a point where I could find interesting images and answers to personal issues, while having a fascinating journey along the way, all for myself. At the time I began this practice, I had no suspicion that I would encounter a goddess. There was no hint that I, not unlike seers and shamans of old, would follow a path to become a bridge between the worlds – the realm we live within, and Her realm.

Since that fateful day I began my journey into the world of the Goddess, quite a few years and waves of experience have passed over me: a move to a different city, the growth into adulthood of my sons, illnesses, the deaths of friends and family members, the making of new friends, the birth of grandchildren, travel to other countries, times of sadness and times of happiness.

Now I‟m telling my story, because the Goddess inspired me – as I believe she will inspire you – to see how there is a path through the darkness of our confusions. I invite you to follow along on my journey through the mist of my confusions and the surprise of my discoveries. I hope that along the way you will feel that you too are experiencing the voice of the Great Goddess, and that you will find her words belong as much to you as they do to me. My wish for you is that her words will inspire you to see that you are part of Her Story, emerging in our times, a story which includes affirmation of the spiritual power of the feminine.

But before you come to that part of the book, let me make a cautionary note, one which the Goddess made to me: have patience, because her words about herself must come first in these pages. Keep an open heart and mind to what you will read.

~~

Before I begin my story of my inner journey, I will narrate the outer journey which is its parallel, my visit to Petra, because knowledge of the site and its history are threads woven into this book. I‟ll weave a capsule narration of Petra‟s physical characteristics and history with a few descriptions of its impact on me. If you wish, you can dive into Chapter One, then use this information as a reference along the way.

So, on to Petra....

I had never heard of Petra, had no special expectations. My husband‟s sister offhandedly suggested it as an excursion site, and we decided to go. To start out early, my husband, children, and I woke to the sound of the muezzin‟s morning call to prayer. As we finished breakfast, honks from our taxi summoned us. Outside the house, we heard the bustle of the everyday: buses, cars, the sounds of Arabic from passers-by on the street.

We motored through Amman, Jordan‟s capital city, passing through its residential areas.

Gradually we came to the edge of the city where the road winds into arid land stretching for miles. The land spoke of the primordial past, of quests, transitions, and transformations. Invading armies, wandering tribes, and caravans came here. Ancient peoples lived here: Edomites, Moabites, Ammonites, Canaanites, Hebrews, Greeks, Romans, and others. I wondered what drew them to this harsh place.

After a four hour drive, we came directly to the Petra hotel, where we found Bedouin guides who led us on horseback toward the Siq, an approach to Petra which is a canyon. Imagine living within a city with an entrance that is a huge cleft in mountain cliffs. Petra is a city encircled by a ring of mountains. The Siq is a miracle of nature, the result of a natural fault that split through the mountain eons ago. Repeated flash floods smoothly contoured its red, brown, and purple sandstone walls. Since Paleolithic times nature provided the peoples of Petra with a natural fortress. Even Rome's legions, able to dominate most of the area between the Eastern Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf by the first century B.C., found Petra nearly inaccessible. Not until 106 A.D. did Rome, under the emperor Trajan, discover a fatally vulnerable point, Petra‟s secret main water supply traveling by aqueduct, at which point the Nabataean kingdom was incorporated into the Roman Province of Arabia.

Traveling slowly through the shadows of the Siq passage, we came to walls rising to three hundred feet at the other end of the canyon. I had not anticipated Petra‟s wild, surreal beauty. Vividly colored, multi-striated sandstone crags testified to the immensity of geological time spans which they represented. Going into the Siq on horseback we left the desert sunlight for shadows like twilight. Many had come here before us. Their ancient markings were etched on the canyon walls. The walls seemed a passageway into another time, another space. More difficult to describe than Petra‟s unique physical characteristics was an intangible factor: Petra had presence.

I saw conduits cut into the canyon walls by the Nabataeans to channel spring water into the city‟s cisterns. Part of the original roadway of paving stones laid down in the bed of the Siq also remained, evoking visions of the traffic that might have passed through Petra two thousand years ago: caravans of camels laden with goods from Arabia going toward Damascus; merchants, noblemen, legionnaires on horseback, and common people on foot; then later, Roman governors, messengers from Rome, Roman architects, artisans, engineers.

We emerged from the dark end of the canyon into intense sunlight. Before us was the most impressive monument in Petra, El Khazneh, carved into a cliff. The facade of this monument reached a height of ninety feet. Characteristic Nabataean carving around the doorframe had not eroded. Roman influence added elaborate pillars, niches, and statues. Footholds ascending the sides of the facade were also visible. I felt as if I could hear voices – workmen, artisans, stone carvers – calling to each other.

Turning away from El Khazneh, we walked toward the valley leading to the city-basin. Before us spread a valley embraced by cliffs. Tiers of tombs were carved into these cliffs. This valley birthed, nourished, and protected generations of human life. We passed a Roman

amphitheater cut into the left wall of rock. The theater had once seated 7000 people. I could easily imagine the roar of the crowds seated here for performances, such as gladiator combat.

To the left of the amphitheater I saw eroded steps cut into the sandstone crags. They ascended steeply to a height not visible from where we were standing on the valley floor. Weary from climbing the ascent, we overlooked valleys with blue haze. We had come to the mountaintop known as the High Place. The altar on the High Place had been one of the official centers of the city's religious life. There were carvings in this mountaintop, an altar, a ceremonial basin, and a rectangular ledge, deeply cut into the mountain top, which surrounded the altar as if to provide space for a congregation.

Because many of the striking structures in Petra are tombs, I was at first most conscious of the Nabataeans‟ concerns about death. Unlike the city of the dead, the Nabataean city of the living, which lay mainly in the mile-wide basin between the rock ramparts, had few traces of freestanding structures.

I was amazed to see tiers of apartments carved into high cliffs surrounding the city basin. Streets of steps, carved into the cliff, ascended to the apartments. I wondered what it might have been like to live inside chambers carved into the face of a cliff. Aware of the love for decorative arts which has long existed in the Middle East, I envisioned embroidered wall hangings on the apartments‟ stone walls; hand-woven, intricately patterned carpets on the floors; divans with a profusion of colorful pillows; charcoal braziers; perhaps even hanging oil lamps dispensing light or fragrance of incense, such as can still be seen in the Middle East today.

Archaeological evidence from these dwellings rests in the Amman museum: bowls, lamps, storage jars, cooking pots, animal figurines, human figurines, offering cups in the shape of animal heads, elegant vases, bottles for perfume and kohl (mascara), bronze pieces, fragments of iridescent glass, and intricate gold jewelry.

These findings tell us that the Nabataeans lived very much in the present. By the time the Nabataeans‟ rapidly developed civilization reached its height in the first three centuries B.C. they were enjoying luxury living.

~~

The Nabataean Arabs had appeared only about seven centuries before. They were the consequence of a drift of tribal peoples, perhaps from the Arabian peninsula. They developed from a wandering people into an effective strike force, raiding caravans that carried luxury goods out of Arabia and the Far East. In time they displaced the Edomite peoples who lived in this mountain stronghold. Before the Nabataeans ever arrived, Orites, Edomites, Moabites, Israelites, and Judaeans, vied to maintain a presence in the great rift valley of the Wadi Arabah, near which Petra is situated. Evidence of human habitation within the region dates back to at least one million years ago when Paleolithic man hunted elephant, deer, and other animals throughout Jordan.

Gradually the Nabataeans made Petra a compulsory stage and a stopover place in the caravan route. Caravans paid dues and tolls in return for protection by authorities against raids by desert nomads. Here the caravan teams of men from the south handed over their goods to be

taken on by new teams to west or north.

Within the span of the Hellenistic period (338 B.C. to 393 A.D) the Nabataeans organized sweeping control of all trade from the southernmost provinces of the Arabian peninsula to the Mediterranean. Under a series of able kings they took advantage of the unrest during the breakup of the Greek Empire, founded by Alexander the Great, and the beginnings of the Roman Empire. By the first century B.C. they extended control over politically weakened areas from Damascus to the northwestern corner of Arabia.

The Nabataeans‟ cultural enterprise matched their mercantile enterprise. They developed their own legal code, administering the huge area from the Red Sea to Damascus; minted their own coins; perfected an alphabet and script that were a forerunner of Kufic and Arabic scripts. Although they had their own language and script, they were conversant in Aramaic, Greek, and Latin. No doubt such versatility was essential to navigating the complexities of a trading culture where proximity to one‟s neighbors and other cultures was a given. One illustration of the extent to which Nabataean life was intertwined with neighboring peoples was an important marriage. The daughter of King Aretas IV wedded the Judeans ruler, Herod Antipas, a figure of infamy in the Bible‟s New Testament.

The Nabataeans were especially innovative in developing a system of irrigation for their many terraced plots of desert land, which they turned into fertile areas of green. They also created an architectural style and produced sculpture which reflected assimilation of other cultures, yet remained uniquely their own; it became part of the worship of their chief deities, the goddess Al Uzzah and the mountain god Dushara. Petra continued to enjoy exceptional prosperity under Roman rule. In the third century A.D. Petra began its slow decline as the main caravan routes were abandoned for other routes. By the seventh century A.D. Nabataea had disappeared. The world did not hear of Petra again until 1812 when a young Swiss-born explorer, Johann Burckhardt, persuaded local Bedouins to allow him entry to the city.

Comments

Dorothy Atalla is the author…

Dorothy Atalla is the author. I am the publicist.