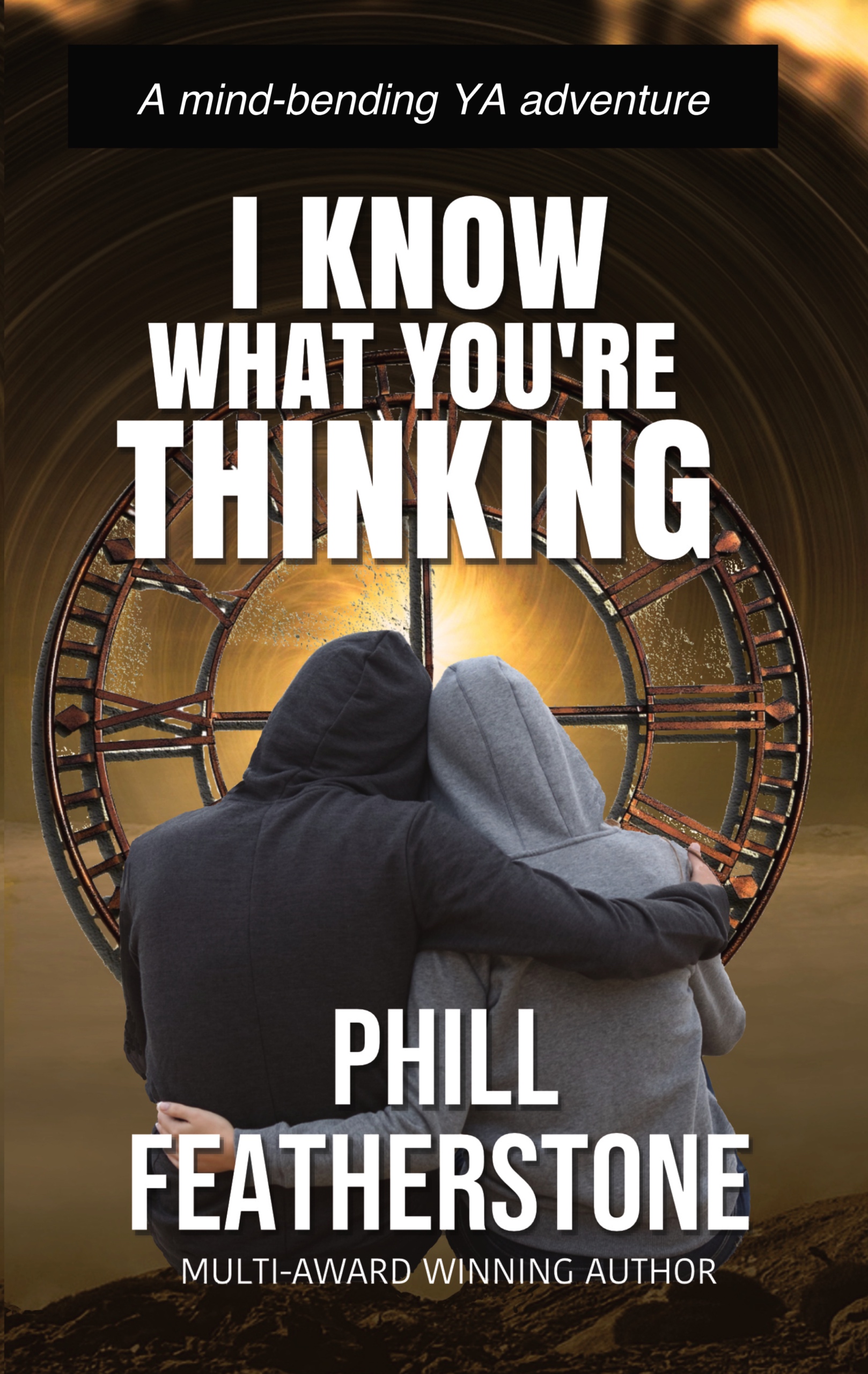

I Know What You're Thinking

If you want to read their other submissions, please click the links.

1.

Beth was lying on her back with Cameron beside her. She adjusted her blindfold. Cameron felt claustrophobic when he wore a blindfold so he didn’t have one, but Beth found it helped. They had agreed that it was better if they didn’t touch, so they’d left a space between them. It wasn’t a very big space but it was there.

‘Ready?’ Cameron said.

‘Yes,’ said Beth, in a voice not much louder than a whisper.

‘Okay. We’ve not done it before, at least not like this, so be prepared for it not to work.’

‘It will work, I know it will. There’s no point trying if we’re not positive.’

‘If you say so. Okay, let’s go.’

Cameron closed his eyes and took a deep breath. Beth started to go through her relaxation procedure. She began at her head and went down her body tightening and then unlocking every muscle group, stage by stage, the way she’d been taught to do in drama classes. Then she moved on to her mind, trying to empty her head of any thoughts, to shut out sounds – the bird outside her bedroom window, the gentle rhythm of Cameron’s breathing – and to reduce to nothing the feel of the mattress beneath her body and the pillow under her head.

She imagined a room with no light and no features; a cavernous dark space lined with black velvet. She let herself sink into the gloom and hung there for a moment. Then she saw a pinpoint of light directly in front of her, as if someone had made a tiny hole in the fabric of the wall to create a window onto a sunny, alternative world. She focussed on the light and slowly it grew into a blob. She knew that the light was important. She must remain completely still and do nothing to disturb it. At the same time she was aware of her own body and Cameron’s, lying side by side on her bed somewhere below her.

The blob of light began to stretch upwards and downwards, lengthening into a line. The line grew, widening at the top. It took on a bluish colour. It began to sparkle as if polished. It developed an edge, and a point that glistened.

Suddenly she knew what it was. She sat up quickly and snatched off her blindfold. The afternoon sun streaming through her window was dazzling.

‘Jesus,’ said Cameron, opening his eyes and jerking upright. ‘What’s up? Are you all right?’

‘Yes.’ She couldn’t hold back her excitement. ‘I know what it is, what you were thinking of. I know.’

‘What was it then?’

‘It was an icicle. You were imagining an icicle.’ Cameron didn’t reply. ‘Weren’t you?’

‘No,’ he said. ‘It wasn’t that.’ She looked disappointed. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said, ‘I really am.’

Beth was deflated. The picture in her head had been so clear. ‘What was it, then?’

‘I was thinking of a dagger.’

For a second Beth was thrown. Then she saw the connection. ‘But I was nearly right. Don’t you see? An icicle is long and thin and it has a sharp point. It’s like a dagger.’

‘Yeah, I suppose it could be.’ Cameron didn’t sound convinced.

‘Of course it is.’ She giggled excitedly. ‘This is fantastic. The first experiment and we were so close. Let’s try again. My turn to send.’

‘Okay.’

They both lay back again and Beth replaced her blindfold. She went through the relaxation routine but this time instead of visualising a black room she reached back into her memory for something that would have meaning for both of them. It wasn’t an object. She recreated a walk in the snow she and Cameron had enjoyed last winter. She remembered a long, straight lane between snowy fields. The lane was lined with fir trees, and as they’d passed them melting snow had sluttered from the branches. She remembered what she and Cameron had been wearing. She heard the crisp crunch beneath their boots. She concentrated as hard as she could, holding her breath, not moving, until she could keep it up no longer. She took off the blindfold and rolled onto her side. Cameron was on his back, eyes closed.

‘Anything?’ she said.

‘Not really. I mean I kept trying. I kept thinking what it might be that you’d want to send me, but there were so many things and nothing came clear.’

Beth was disappointed. ‘I don’t think you should be trying to think of anything,’ she said. ‘The idea is that you empty your head and make your mind a blank. If you’re expecting a particular image it will push what I’m actually trying to send you out of the way.’

‘Mm.’ Cameron was doubtful.

‘Look,’ said Beth, sitting up again. ‘I know you’re not sure that this works but let’s give it another go. When I was the receiver what you were thinking of got through to me, didn’t it.’

‘Sort of,’ said Cameron.

‘It did. When I remember what I saw, it could have been a dagger. It’s just that I mistook what it was. Give it another go, okay? Send me something.’

They lay down, and Beth again covered her eyes. Cameron took hold of her hand. She tried to clear her head but this time it was harder. She couldn’t shift the image of the lane in the snow that she’d been attempting to send to Cameron. Every time she tried to recreate the velvet room and the blackness, the frosted trees and the frozen ruts pushed their way in. She sat up, took off her blindfold and dropped it beside the bed.

‘What’s up?’ said Cameron.

‘It’s no good. I can’t get out of my head what I was trying to send to you.’ She slid her legs off the bed. ‘I think I need to take a break.’

‘What was it that you were trying to send me?’

‘You remember when we walked along that lane in the snow, last year, you know, when you told me I was the only girl you’d really loved? Well it was that.’

‘Holy shit!’

‘What?’

‘That’s what I was trying just now to send to you.’

Beth was lost. ‘You mean you were thinking of the lane?’

‘Yes. And the snow, and when we stopped under the trees and a great lump of it came off a branch and just missed us. All that.’

‘Why? What made you think of that? Why remember it now, so much later?’

Cameron shook his head. ‘I don’t know. It just came into my head.’

‘But that’s what I was trying to send to you. Just now. When you were the receiver but said you didn’t get it.’

They both looked at each other.

‘Oh my God,’ said Beth. She was so excited that the words caught in her throat and she could barely get them out. ‘Don’t you see? You did get it. It worked. You knew what I was thinking.’

2.

Being able to share each other’s thoughts wasn’t new. For as long as they’d known each other, which was the year they both started school, Beth and Cameron had been aware of a curious link between them. It showed itself in lots of small ways. For example, they’d both start to speak at the same time and be saying the same thing. Or they would turn up to a friend’s birthday party each with an identical gift. At meals they’d nearly always make identical choices. Beth would know what Cameron wanted for Christmas before he’d said anything to anyone about it. Cameron would know what bedtime story Beth had had the night before.

At first they themselves didn’t think it was anything unusual. It had always been like that. Then adults started to notice. ‘Anyone would think you were twins,’ Beth’s Gran said. It was often treated as a joke. Archy, Cameron’s friend, said it wasn’t surprising that they both thought the same thing because they’d only got one brain between them. Some of their other friends treated it with the same amused indulgence, the rest ignored it. Most of the adults reckoned it was just coincidence. Gran thought it was cute. So did Molly, Cameron’s mother. Zak, his step-dad looked for ways to explain it.

That was when they were younger, but not long after they moved to secondary school it became an issue. At the end of their first term they were hauled before their head of year. They were puzzled to know why, and were astonished when they were told that the answers they’d given in a history test the day before were virtually identical. The teacher put their work side by side and demanded to know which of them had copied from the other and how they’d managed to do it. Beth and Cameron were bewildered and denied they’d cheated. The teacher didn’t believe them. She pointed to their answers; not quite the same and just different enough, she said, to hide their deception.

They were interviewed independently and each insisted that the work was their own. They were put in detention; it was not for copying, the head of year explained, but for failing to own up to it and tell the truth. Cameron was moved to another group which did different work and so the problem didn’t arise again, but they’d acquired a reputation which it took them some time to shake off.

Beth was convinced that they had a special gift, Cameron not so much. He believed that what was going on was mostly fluke with a lacing of coincidence, and that it wasn’t surprising because they spent so much time together. He told her that telepathy was a load of rubbish, and he dug up online articles debunking it. Beth challenged him to give another explanation for what they experienced. He couldn’t. She also pointed out that many scientists agreed that there was a lot about the mind that was still not fully understood, and she talked about reports she’d found in her own explorations of the internet that dealt with aspects of the brain outside the five recognised senses: for example, the functioning of mirror neurons, and the work sponsored by Elon Musk on ‘neuralinks’. They never had a full blown row about it but they had some vigorous discussions.

Cameron said he’d prove once and for all that telepathy was nonsense. He persuaded Beth to carry out a test which he’d found online. It used a pack of ‘Zener’ cards, five sets of five cards, each set bearing a different symbol – a circle, a square, a cross, a star, and wavy lines.

‘What do we have to do?’ said Beth.

‘One of us is the sender and the other the receiver. We sit back to back. The sender puts the pack of cards face down and turns them over one by one. They concentrate on the card and try to transmit that symbol to the receiver.’

‘And the receiver writes down what they think it is.’

‘Yes. We do that for all the cards in the pack. Then we check and see how many are right.’

‘How many times do we do it?’ said Beth.

Cameron consulted the instructions. ‘It says here you should go through the pack five times. It will take a while.’

‘All right,’ said Beth. She didn’t believe the experiment would tell them anything; she knew that they had a connection but she’d decided Cameron should be humoured.

For their first run Cameron was sender and Beth receiver. When they were done they went through Cameron’s pile of cards and checked them against the list Beth had made. They were astounded. Ten of the twenty-five cards on Beth’s list were correct.

Beth was exultant and even Cameron was impressed. ‘Unbelievable!’ she gushed. ‘Let’s do it again. I’ll send, you receive.’

On this second run the score was two.

‘Oh,’ said Beth, disappointed. Perhaps she was a more effective receiver than Cameron and he was a better sender. It could be that it was more successful that way round. She handed him the cards. ‘Again. Really concentrate now.’

‘Yes, miss.’

They repeated the test and this time the score was three.

‘Well at least it’s going up,’ said Cameron.

‘Yes, but it’s not even average,’ said Beth. ‘With five of each symbol you’ve got a one in five chance of being right.’

They did it again, and scored another two. Then four. Then they gave up.

‘Useless,’ said Cameron. He checked their results on the ready reckoner that had come with the cards. ‘Twenty-one correct out of a hundred attempts. It says that’s “insignificant”. Pathetic!’

Cameron felt vindicated. Fond as he was of Beth, there was no mysterious mental link between them. She didn’t know what was happening in his head, and he confessed to himself that sometimes that was a good thing. He certainly had no idea what was going on in hers. Then something happened that changed his mind.

He was with Beth on a patch of waste ground. It was the site of an old factory where there was a concrete pan that was good for skateboarding. At the edge of the site was a huge mound of earth and rubble, and some lads were on top of it messing about with an old tyre they’d found. The tyre was huge, perhaps from a tractor, and they were having trouble handling it. Cameron climbed up to join them, Beth stayed at the bottom with her Gran’s dog. She bent down to rub the animal’s head, and just then the boys lost control of the tyre and it started down the mound. Beth had her back to it and it was obvious she was directly in its path. Cameron tried to shout but no sound came, he couldn’t utter. It was as if his throat was paralysed, but inside his head he screamed at her to move. Beth felt a sudden lunge, like a hand in her back pushing her aside. She staggered and the tyre bounced past, missing her by inches.

She swung around and saw Cameron and a couple of his friends scrambling down towards her.

‘Shit, that was lucky,’ one of them said.

‘Sorry,’ said the boy who’d let go of it. ‘I didn’t realise it would go like that. Good job you got out of the way.’

‘Yes, it would have flattened you if it had hit.’

Beth could see it had been a near miss. The tyre was big and heavy; if it had struck her it would have done her harm. She also knew that her escape wasn’t down to chance. When they were alone she and Cameron talked about it.

‘Thank you,’ she said.

Cameron was shaken by what had so nearly happened. ‘What for?’ he said. ‘I didn’t do anything. I tried to shout but something stuck in my throat and I couldn’t.’

‘You didn’t need to. I felt you helping me. It wasn’t a voice in my head or anything like that. It was like you were shoving me out of the way.’

Less than a week later it happened again. This time they were going for a bus to take them into town. Cameron saw it coming. ‘Come on,’ he shouted, and made to run across the road. Beth was behind him and she froze; he was about to career into the path of a car. At that same instant Cameron felt something hold him. It was like a fist grabbing his shirt so he couldn’t step off the kerb, and the car brushed past him. Beth stood open mouthed. She hadn’t actually done anything but she knew that somehow she had protected him.

Beth needed no more evidence that their minds sometimes connected. She didn’t know how or why, but these things couldn’t be just coincidence. She wanted to challenge Cameron’s scepticism and prove to him once and for all that they really had an extrasensory link. So they set up the experiment in her bedroom, and Cameron was at last convinced. He had to accept that for reasons neither of them could fathom one was able to reach into the mind of the other. However, it wasn’t something they could rely on being able to do; it just happened sometimes. ‘Pity,’ Cameron said. ‘If we could manage it all the time we could make some money out of it.’

Cameron bought a bottle of wine, they found a quiet corner of the park to drink it, and they talked. They agreed that the favoured tests of telepathy, like trying to reproduce sequences of cards or find objects that had been hidden in a room, were a waste of time. What connected the two of them wasn’t something mathematical or scientific: it was emotional and beyond understanding. The only sensible way to handle it was to talk frequently about what they were doing and what they were planning to do, so that they could avoid being labelled freaks – obviously what some of their friends thought.

As they went through their teens they grew closer, and their relationship progressed from friendship into something more. And as they developed a physical attachment the mental bond between them became even stronger. Not always but often each would know what the other wanted, or didn’t want, without putting it into words. When a year ago Cameron got set on by a gang of hooligans and his mobile was taken, Beth knew something had happened to him and went to find him. When Beth took her Grade 8 piano exam Cameron was scarcely able to sleep the night before, and when he did drop off the dream he had was very like the one Beth had in her own bed in another part of the town.

They realised that they were privileged to have such an amazing gift. They didn’t know that one day it would save Cameron’s life, and almost cost Beth hers.