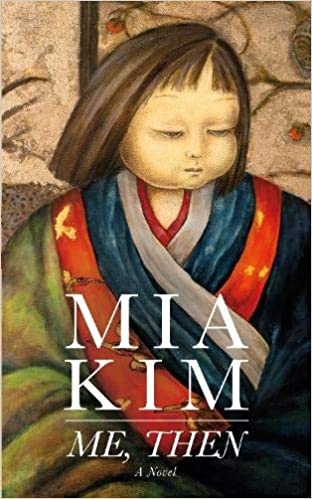

Me, Then

Chapter One

1964. Seoul, Korea

Red drops plopped on my shirt, little dots unfolding, expanding like the petals of a late summer’s touch-me-not. I felt the wetness drip from my nose to my lips. A metallic taste. I swiped at it and gasped, less from pain than the shock of seeing blood. I’d never seen my blood before, or any blood. Just then, Mrs. Han swooped down, pulled me up by my hair, and smacked the side of my head. The force threw me against a tree—just my luck to hit the lone tree in the front yard—I bounced off it and fell forward on my face, scraping along the gravel, my chin and palm burned. I started to push myself up, only to stare at Mrs. Han’s feet in front. She grabbed me once more, I crouched against her next blow, but it didn’t come. From out of nowhere, Mom lunged in and blocked her fist, taking the hit herself. Mrs. Han looked stunned, me too. Mom wasn’t to come for another three days. Mrs. Han stammered, blurting out that I was clumsy and fell, all by myself, but before she could say more, Mom put me on her back and ran out of the house.

She fast-stepped through the narrow alleyways, my chin banging against her shoulder like a woodpecker. If I weren’t piggybacked, she would’ve sprinted. The sharp morning sun stung the back of my neck and arms. I covered Mom’s bare arms with my hands, shielding them from the sun. She asked if I could walk; I was getting too heavy and too hot. I shook my head, clinging tighter to her sweat-soaked back. With my head resting on her damp neck, smelling her hair, I’d already forgotten the beating. I was happy on her back, as if I were in her womb again—floating and safe, moving without moving.

The narrow streets on the edge of Seoul were empty except for a scrawny dog that snarled and barked, spit bubbling from his jagged teeth. Dogs were never pets, but ferocious guard dogs or feral strays. Mom marched right past him. I, normally terrified of them, stuck out my tongue, secure on her back.

Mom slowed when we turned onto a wide tree-lined boulevard. The shops were waking up: merchants cranking up their iron-rollup doors, an old man hanging up his wares on the doorframe hooks, a woman splattering her storefront with a bucket of water to settle the dust. People passed us without wasting a smile. Mom stopped in the shadow of a tall tree, catching her breath. I wanted to ask where we were going, why she came three days early, but didn’t. My few clothes were still in the corner of Mrs. Han’s living room; I kept quiet about that too.

Through the gnarled tree branches, Mom gazed up at the sky, her habit whenever she was thinking. I squinted up too. The sun played peekaboo, flickering between the leaves. Mom patted my bottom, rocking me side to side, reassuring me that all was well, but soon, she let out a long sigh and sank down. She sobbed. It frightened me; I’d never seen her cry. I wriggled myself down from her back and toddled around her. I was really sorry I made her sad; I wished she’d spank me if it would make her feel better. All this—her crying, our running sweaty with no place to go—was my fault, all because the night before I’d committed a crime and got caught.

Four days ago, Mom brought me to Mrs. Han who met us at her gate that opened onto a large walled-in courtyard. She beamed at me, pinched my cheek, in a friendly way, and led us across the clean-swept courtyard to an immaculate, spacious living room. Her house was a stately, traditional Korean home with a grooved slate roof that fanned upwards in the corners. As people normally did in hot weather, she had opened the living room shoji doors wide, letting the breezes through the front and back yards. Made of thin wooden lattice and covered in semi-opaque rice paper, shoji doors let the sunlight filter in, and also slid from side to side, dividing the rooms efficiently. In the front yard, the shy and modest touch-me-not plants dotted along the base of the wall; in the backyard, colorful peonies and wild roses erupted, giving a lush, gay air to this otherwise solemn and orderly house.

Mrs. Han was tall like Mom, a bit skinnier, but her mouth terrified me. It was alive all on its own. From her protruding purplish gums, pointed teeth jutted out in all directions, jam packed, each elbowing for space; when she wasn’t speaking, her darting tongue licked her upper lip over and over again.

“Unni, thank you so much. I’ll not forget this,” Mom said, handing Mrs. Han a roll of money which she quickly dropped into her skirt pocket. “Unni” meant older sister, a term often used as a mark of respect when a younger woman addressed an older female. It also bonded them.

“Don’t mention it. You are like a sister to me. If I weren’t so hard up, I wouldn’t take your money. Ah-gha should call me ‘aunt’ from now on,” she said, catching my eye, smiling.

Mom swung me around onto her lap and smoothed my hair. “My little puppy, my little monkey . . . Ah-gha-ya, can you show me how many days are in a week?”

That wasn’t difficult, I was almost five years old. I counted them out on my fingers.

“How smart you are.” Mom patted me. “So, one finger for one day. When you’ve counted off seven, I’ll be back. Till then, be good and obey Mrs. Han, yes?” She stood up. I tried to climb back into her arms, but she held me away and dashed out of the door, out of sight. I tried to run after her, but Mrs. Han gripped my shoulders, pulling me back.

“No, you stay with me. You’ll be alright here.” I screeched for my Mom to come back as Mrs. Han walked to the gate and locked it.

There were no other kids in Mrs. Han’s household, only seven adults. In the morning, everyone moved about frantically except her father and grandma. Mrs. Han, her three brothers and her mother all squatted in a semicircle around the water pump in the backyard, washed their faces and arms in a great rush, then trotted back to their rooms to get dressed. Soon after, all sat around the low table in the living room, ate quickly, and bolted out of the gate. Then the house stood still like a headstone in a forgotten cemetery.

All day long, grandma, who could barely see or move, sat hunched over in the corner of the living room, mending clothes and sewing on buttons with her knobbly fingers. Her small crumpled face poked out from her voluminous Korean dress. Through her huge magnifying glasses perched on her hooked nose, her unblinking, gigantic murky eyeballs peered out at me like an owl. Everywhere I turned—the walls, the closed doors, the spotless grounds—all seemed to say, “Don’t touch. Stay away.” So, I kept near grandma, and when she didn’t shoo me away, I inched closer to her like a hesitant spider doing a sideways dance, and watched her sew.

A day frozen in time; nothing moved except for grandma’s fingers and the clouds that played hide and seek with the sun, turning everything dark one minute, bright the next. From inside her rolled-up sleeve, grandma fished something out, put it on the floor and went on sewing. It was a piece of hard candy which I cautiously picked up. The wrapper was stuck tightly round the candy, so I put the whole thing in my mouth and let my saliva work its way into the wrapper; the sweetness was heavenly, the sourness made my mouth water. Grandma gazed at me, the corners of her sunken mouth upturned in a smile, her watery eyes warm.

In the centre of their generous front yard, a gorgeous almond tree towered over the house, its many zigzagging branches heavy with clusters of white delicate blossoms spilling over the wall to the street beyond. Day and night those tender little flowers fell to the ground, swirling like baby butterflies. Mrs. Han’s father swept away the fallen petals as many as three times a day, unhurriedly, with great care. He also wiped clean the outsides of a dozen or so large urns standing against the backyard’s stone wall, patiently waiting for autumn when they would be filled with preserved food—a half dozen different kinds of kimchee, fermented soy beans, and hot pepper pastes—enough to last the entire winter. I wanted to help sweep and clean, even pick up some fallen petals to play with, but I didn’t ask. Something told me that even the dead petals belonged to him.

Mrs. Han and her mother came back in the early evening. After changing their clothes, they went on to cleaning—no chatting, no laughter, just an obsession with their already spotless, shiny home.

The three brothers stumbled in shortly before the midnight curfew, their faces bright red from drinking, their rubbery arms and faltering steps knocking and kicking along the walls and doors, but without the loud, rough talk of drunkards.

All eight of us slept in the large living room with shoji doors wide open, the only place where the night air lazed in and out. The three brothers slept at one end, then the father, mother, and Grandma. Mrs. Han and I slept at the other end, me against the wall. As the adults slept they snored, some loudly and for long periods. Mrs. Han’s throat rattled each time she inhaled; Mr. Han puffed and blew, while the others gurgled, wheezed, and whistled, loud enough to be heard above the cicadas’ manic buzzing. Whenever the cicadas paused, the crickets took over. I was lost for sleep, my ears tuned to the uneven rhythms of the night’s great chorus.

Laying still, I checked my to-do list. I had three things to find out: who’s kind and who’s not, and where to hide. So far I avoided everyone except Grandma, and I hadn’t found my hiding place yet since I wasn’t sure where I was allowed to go and where not; rooms were always closed shut but more out of orderliness than privacy, I thought. There was the storage space next to the outdoor kitchen where the bushels of rice and other dried goods were kept, but I ruled that out: rats ran loose there. I knew this because I’d seen them in other homes.

Before coming to Mrs. Han’s, I lived with a woman who ran a food stand selling kimbap in Seoul train station. She was youngish, but bent like an old lady, walking slowly. She was gentle and soft-spoken and lived alone. Each day she got up in the black of night to make kimbap—rice, spinach, thin slices of fishcake and carrots all rolled inside a sheet of dried seaweed. She sliced each roll into bite-size pieces and arranged them in paper-thin, throwaway bamboo boxes. The delicate dried seaweed sheets tore easily, and no matter how carefully she rolled them, very often the contents spilled out. We ate the ruined pieces and the uneven ends. She then stacked the kimbap boxes on her small cart that doubled as a food stand and pulled it through the snaking sleepy streets, sometimes carrying me on her back, more often, with me walking alongside her. By the time we arrived at the train station, the sky glowed with the dawn’s cool blue.

One especially hectic day while she was tending the lunchtime crowd, I wandered off, dazzled by the stands all around us selling their wares; paper fans, pillows knitted with multi-colored plastic straws, hats woven with bamboo strands, shoes made from rubber, with their front tips painted in pink and green, makeup for the ladies, shirts, dresses—any and all things people wanted and needed before they hopped on the train. I was drawn to one special stand. It sold candies, cookies, shrimp crackers, and other snacks. I stood glued to it, staring and staring, imagining their smell, feel, taste. Before I knew it, I was on tiptoe, my fingers stroking a piece of gum, wrapped so alluringly in yellow paper and silver foil. I picked one up; it wanted to be picked up. Wham, a hand swatted my wrist, the gum fell back into its place and I was swooped up into the kimbap woman’s arms. She was shaking and in tears, almost hysterical; she’d been searching all over for me. That was the end of my stay with her.

The nights were long in Mrs. Han’s house, the nocturnal chorus of snoring and insects intense. Mostly I was too hungry to sleep, but I dared not ask for more rice. Mrs. Han’s toothy smiles on that first day with Mom never came back. Now with her mouth clamped shut, she looked right past me, pointing her finger or lifting her chin up or down for me to come or go; mainly I stayed out of her way. To be fair, everyone ate sparingly: breakfast, normally the biggest meal of the day, was half a bowl of rice, kimchee, a clear broth with thin radish pieces floating on it, and a clump of sweet and salty black beans; lunch was a bowl of cold noodles mixed in hot red paste, so spicy hot it brought tears to your eyes; dinner included a piece of fish, rice and pickled cucumber slices. Mrs. Han gave me whatever was left over after serving the grownups.

On the fourth night the trouble began.

An enormous moon beamed on the sleeping bodies, bright enough for me to see a patch of black hair feathering out from Mrs. Han’s underarm. As I didn’t have any, I watched hers with a great curiosity. Something about it was creepy, even threatening. What if they grew and grew, spreading out, overtaking her, turning her into a black-haired monster, her face filled with gigantic jagged teeth. Don’t spook yourself, I told myself, and turned away.

The moonlight also glinted on silvery fish scales from a string of fish hanging from the wall, drying, five in all, each the size of a flattened zucchini. My stomach growled. I wondered if dried fish tasted like the dried squid people ate as snacks. The more I stared, the hungrier I got. They were dangling right above me, close enough that I wouldn’t even have to stand on tiptoe. I got up, tugged at the bottom one. The fish loosened from its string. I put it under my nose—my habit of smelling things before putting them in my mouth—a mild rotting odor stung my nostrils, but I convinced myself that it smelled a bit like dried squid, so it should taste like one too. I bit at the tail end where it was driest and least smelly, and holding my nose, I chewed it fast and gulped it down. But it didn’t go down; instead, it got stuck at the back of my throat. I gagged and flailed, and fell right onto Mrs. Han’s head. She yelped and shot up. Everyone woke up. Someone turned on the light. Someone else smacked me on the back. I coughed out the fish chunk, tears blinding me. Mrs. Han shook her head, her face furious. She shoved me back to my corner, telling everyone to go back to sleep.

Soon, the cicadas blasted again, and the rattling throats, too. I curled up, working to stop my teeth from chattering, hoping that by morning Mrs. Han would have forgotten the incident.

She hadn’t. She shook me up from my sleep. As I came to, she whacked me: “You filthy runt! So little and already stealing. What a monster you’ll grow to be! I will beat the thief outta you.” Her mom, father, Grandma, and brothers watched silently as she grabbed a fistful of my hair and threw me against the wall.

When Mom took me away from Mrs Han’s, I hoped never to see her again, but we did.

Chapter Two

We stopped in front of a small store on a wide, hectic, down-sloping street. On either side, shops stood shoulder to shoulder, almost falling over one another. One-story shops squeezed against multi-story buildings. Some were old and crumbling, others gleaming, new and tall like giants among elves. Past and future dying and birthing all around. Cars, people, vendors all jostled for space. A man on a bicycle struggled to pull a large cart with crates piled on high, like an ant hauling a leaf a hundred times its size. Women carried big round bundles perfectly balanced on their heads, babies on their backs, deftly walking between the cars. A pedlar split open a watermelon from his cart, showing off its riotous red flesh and black seeds, bursting of summer. He shouted he was there only one day, but everyone knew he’d be there tomorrow and the day after tomorrow as long as the watermelon season lasted.

We were in an area called Ah-hyun Dong, Mapo Gu, an energetic, fast growing district. It sat just above the Han River, which cut through the bottom third of Seoul.

Mom pushed the shop door in. A bell tinkled. Muggy hot air outside melded right in with the musty, stuffy air inside. An electric fan in the far corner creaked from side to side. Rolls of fabric leaned against one wall, their edges flapping madly whenever the fan turned towards them. Near the window were two sewing machines, shiny and black, their graceful necks adorned with golden letterings, their foot pedals idling below.