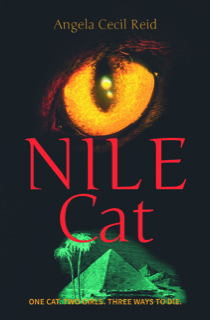

Nile Cat

It was just after dawn when I leaned over the ship’s rail and watched the man who wanted to kill me, ride away on a donkey. His legs were so long that his feet almost touched the ground. He was urging the donkey forward. It wouldn’t move.

‘Look Rose, it’s Mr Baxter,’ said my sister Lily.

‘I can see that.’ I would recognise that spindly figure with his mop of grey hair and thick, round spectacles anywhere.

The donkey boy pulled the lead rope but the animal’s hooves were planted squarely in the dirt and its ears were back. Mr Baxter raised his hand, and I realised he was holding his silver-topped walking cane. The cane came down hard on the donkey’s back, once, twice, three times. The donkey brayed and flicked its back hooves high into the air. Then it set off at a gallop with its rider hanging on tight to the saddle, his elbows and legs flapping like a pull-along toy. The donkey and its rider disappeared in a cloud of dust, the donkey boy in hot pursuit. I would have laughed if I’d been less afraid.

‘Why did he have to hit it?’ said Lily. ‘He could have waited for the boy to get it moving.’

I nodded. But I knew Mr Baxter would not care about hurting a donkey. ‘I hope he never, ever comes back.’

‘You hope who isn’t coming back?’ Papa’s voice behind us made us jump.

He was looking very smart in his lightweight tweed suit and waistcoat. His moustache and sideburns were freshly trimmed, and his hair combed smooth and neatly parted.

‘Mr Baxter,’ said Lily, ‘has vanished on the back of a donkey.’

‘Really?’ said Papa. ‘He wouldn’t have had his luggage with him then. Not much room for luggage on a donkey.’

‘No age,’ I agreed.

‘Then he’ll be back before the ship leaves.’

‘He hit the donkey with his cane. Three times.’

Papa raised an eyebrow. ‘Donkeys can be very stubborn. Sometimes that’s the only way to get them moving.’

I glared at him.

He shook his head ‘Sorry, Rose. Not everyone is as concerned about animals as you are. For many people here in Egypt, life is hard. It’s not a surprise that their animals have a hard life too.’

I supposed he was right. Life was hard in London as well. I’d seen horses like skeletons, struggling to pull their heavy loads through the streets. I hated it.

‘But Mr Baxter isn’t poor,’ I protested. ‘He is travelling First Class. And I hate him not just because of hitting the donkey but also because he follows us, Lily and me. Wherever we are on the ship, there he is. Watching us. He scares me.’

Papa frowned. ‘Why on earth would he be the slightest bit interested in either of you?’

I shrugged. ‘I don’t know. But he is.’

Papa shook his head. ‘Your imagination will get you into real trouble one day, young lady.’ He pulled out his pocket watch and studied it. ‘Now I must go or I will be late for my meeting ashore. Coaling will begin soon and it is a terribly dusty, dirty business. So your mother wants you back in our cabin before it starts.’

‘But Papa,’ I protested, ‘do we have to go right now?’

‘Perhaps,’ he said with just the hint of a smile, ‘you can stay for a few more minutes. But the moment the dust starts flying, you must both go to your mama, particularly you, Lily. We haven’t brought you all the way from England to escape the London pea soupers for you to breathe coal dust here.’

When the fog swirled up the River Thames from the sea, it mixed with the coal dust in the smoke from all the factories and the fires in everyone’s houses. Sometimes it was so thick it was hard to see a foot in front of you. Or even breathe. Then we called it a ‘pea souper’. It often lasted for days and could kill people with weak lungs like Lily. She had pneumonia when she was just a baby and nearly died. Her lungs never fully recovered and when the air was bad she struggled to breathe.

The early morning sun warmed our backs as we leaned over the rail and watched Papa cross the gangplank and walk purposefully away. Behind us lay the clear blue waters of the Mediterranean, in front of us was the bustling city of Port Said. It was a whole new world of low flat-roofed houses and palm trees.

Since Mr Baxter and the donkey had vanished at a gallop, I didn’t know what to feel. I’d longed to come to Egypt ever since I’d been really little and Papa, who was an Egyptologist, had started telling us stories about the Egyptian gods and kings. Now that I was actually there, all I wanted to do was return to the cabin, lock the door and wait for the ship to take me home.

‘What’s wrong, Rose?’ asked Lily staring anxiously at me. ‘Are you really still worrying about Mr Baxter?’

It was my job to look after Lily, not to fill her head with worries. ‘I am sure you and Papa are right,’ I lied. ‘Maybe I’m just not thinking clearly because I slept so badly.’

She didn’t look convinced.

‘I had such peculiar dreams,’ I added quickly, hoping to distract her.

Lily frowned. ‘Not your old nightmare?’

‘No, it was different.’

‘Tell me.’

I gazed at Lily for a moment, deciding what I should say. It was like looking into a mirror. Copper-red hair, green-flecked eyes and pale, pale skin. Except in Lily’s case her hair was twisted into neat, shiny ringlets, while my hair hung straight to my shoulders. She was my older sister, but only by twenty minutes. We were fourteen years old and twins, but even though we looked the same on the outside, inside we were very different.

‘You know when your hair is washed, you get water in your ears and you can’t hear properly? It was like that. I could hear voices but they made no sense, the words were like gurgles. I couldn’t see properly either. It was like looking through Papa’s magnifying glass. When you hold it too close to something, it goes all blurred.’ I shivered, remembering how scared I had felt as I struggled to make sense of it all. And how I had failed.

‘I see,’ said Lily with a frown.

But it was clear she didn’t see at all. I closed my eyes for a moment. I needed to think, about Mr Baxter, about my dream, about the secret I mustn’t tell...

I could feel Lily’s eyes on me. ‘There’s something wrong, isn’t there?’

One of the most special things about being twins was that we often had the same thoughts at the same time. Lily always said it was just coincidence, but I was sure it was more than that. It was like our minds were linked somehow. And trying to keep secrets from her felt wrong, like wearing boots that didn’t fit. I needed to distract her.

‘I was just thinking,’ I said brightly, ‘that two weeks ago we were in freezing, cold London and now we are here in Egypt. Isn’t it wonderful?’

She didn’t reply at once. Instead she adjusted her hat so that its brim shaded her face, patted her ringlets into place, smoothed out an invisible wrinkle in her skirt and gave a deep sigh. ‘I think being in Egypt will be all right. But I wish Mama and Papa would not fuss about me so much.’

‘At least they care about you.’

Slipping her arm through mine, Lily said, ‘They care about you too, silly. It’s just my lungs. If they worked properly, then they would treat us just the same.’

I doubted it. Apart from breathing and maybe drawing, Lily did everything better than I did. But she needed looking after. Autumn in London had been unusually damp and cold, so Lily’s cough had been particularly bad. Papa had thought the warm, dry air of Egypt would be good for her.

I hated to think how ill she might have been if Papa hadn’t decided at the very last minute that we must all come with him on the SS Australia. He works for the British Museum and usually spends the winter up the Nile excavating tombs in the Valley of the Kings. This was the first time we’d been allowed to come too. So far, Papa’s plan had worked. I hadn’t heard Lily coughing for days. The fresh sea air had already done her lungs good.

‘But it’s not just about your lungs, is it?’ I complained. ‘It’s other things too. Like Mama saying how you always look as neat a new pin. She never says that about me.’

Lily giggled. ‘I can’t think why. Have you seen yourself today?’

‘No.’ My head had been too full of my peculiar dream – and Mr Baxter – to worry about mirrors. As usual Lily’s calf-length linen skirt and her cotton blouse looked as if they had just arrived fresh from the laundry, and her bootlaces were neatly tied in double bows. I glanced down at my crumpled skirt and my knotted laces, and sighed.

Lily was leaning over the railing, peering down at the scene below us. ‘I expect you are longing to draw all that.’

Normally, I’d love to sketch the disembarking ladies who looked like a flight of rainbow-coloured butterflies, and the little grey donkeys in their brightly coloured harnesses standing patiently beside the donkey boys in their ankle length robes, or galabeyas, as Papa had told us they were called. There was even a heavily laden camel. All of this should have been irresistible. But not today. Even though I had my little tin of charcoal and drawing chalks in my pocket as usual, my sketchbook was in the cabin, and it could stay there.

Just then a seagull swooped low over the deck then soared up to the very top of the mizzen mast, where it perched to preen its feathers. When Lily and I’d first seen the ship and realised it had a funnel as well as sails, we’d been impressed. It was so very modern.

‘When does the ship sail and when does it steam?’ I’d asked Papa.

He had explained that when the wind blew in the right direction for the SS Australia to sail on her course, then the sails would be unfurled, otherwise the engines would be stoked up and we would steam our way through the waves. To make enough steam, she needed coal. Lots of it. Port Said was where her coal bunkers were to be filled for the voyage through the Suez Canal and onwards to India and finally to Australia.

I climbed up onto the bottom rail and leaned right out over the side so I could see further along the street. To my enormous relief, there was still no sign of Mr Baxter. Before Lily could ask me what I was doing, I said, ‘I was just wondering if Aunt Dora had received Papa’s telegram saying we were all on our way to stay with her in Cairo?’

‘I suppose she will still be in mourning for Uncle Arthur.’ Lily paused, then smiled. ‘Perhaps she won’t want us and we’ll go to stay in a grand hotel. I’d like that.’

‘But maybe she will like some company anyway? She must be lonely since Uncle Arthur died.’ Our uncle had also been an Egyptologist. He and Aunt Dora had lived in Cairo for years, and Papa often stayed with them when he was in Egypt. Uncle Arthur had died in the spring. Papa told us his heart had failed suddenly and there had been nothing anyone could do to help him.

Lily nodded. ‘But I hope Aunt Dora won’t take us on endless expeditions to tombs and temples and up pyramids. I know you loved all those stories about the ancient Egyptians Papa used to tell us, but I thought they were dreadfully boring.’

I had to laugh. ‘Honestly Lily, if Aunt Dora doesn’t take us round all those places, Papa will.’ Another thought made me smile. We were going to see Max. And he might show us round, and even Lily would like that.

I glanced at her. She was staring into the far distance beyond the wharf. ‘What are you thinking about?’ I asked.

‘Max,’ she said.

Of course. I’d thought of Max, and so she had too.

Max was our elder brother, and he was the best brother in the whole, wide world. He was kind, funny and really clever. He was eighteen now and had left school last summer. He was training to be an Egyptologist on an excavation near Alexandria. We missed him terribly. But he probably didn’t miss us much given that his nickname for us was still “the Holy Terrors,” even though we hadn’t played tricks on him for years.

‘Of course he will come and visit us in Cairo,’ I said, ‘and maybe later on we can go and see the tomb where he has been digging.’

At that moment, a soft voice came from behind us.

‘Excuse me, ladies.’

We swung round. Hakim, our cabin steward, was standing a few feet away. ‘I am most sorry, Miss Lily, your mother insists you return to her now.’

Lily sighed. ‘I’m just coming.’ She looked at me. ‘Don’t be long, Rose,’ and then she and Hakim were gone. As I watched them disappear inside and I was left alone, all my fears came flooding back.

CHAPTER 2

It had been Hakim who had welcomed us on board that very first day in Southampton. A dark-skinned, dark-eyed steward in a spotless white jacket with shiny, silver buttons had introduced himself.

‘My name is Hakim,’ he’d said with a small bow and a huge smile. ‘I am to be your cabin steward. Anything at all that you want, I can find for you. If you have questions, I will attempt most hard to answer them. Now please to follow me.’

So, we followed him. Everywhere I looked there was dark varnished wood and gleaming brass. We passed the saloon, furnished with long, narrow tables and benches.

‘This is where you will eat your meals during the voyage,’ explained Hakim.

There were also clusters of green leather armchairs and small tables at each end of the saloon where several passengers were already sitting reading newspapers or playing cards.

‘Will this be your first visit to Egypt?’ Hakim asked me as we walked.

I nodded.

‘You will have a most wonderful time. Are you visiting the great pyramids?’

‘Oh yes,’ I said. ‘I’ve wanted to see them since forever.’

Hakim smiled. ‘They are indeed most magnificent.’ He turned to Lily. ‘And you, Miss, are you looking forward to seeing the sights of Egypt?’

‘I’m sure they will be very nice,’ she said carefully, ‘unless I die from sea sickness before we get there.’

Hakim’s brow furrowed. ‘I am most certain that will not be the case. I have a most efficacious tonic made from ginger and a touch of liquorice, which I will bring for you if you feel unwell.’

I didn’t dare look at Lily as I knew how much she hated both ginger and liquorice.

‘That’s quite enough chatter, girls,’ said Papa from behind us. ‘I am sure Hakim doesn’t want to know all our business.’

Hakim shook his head. ‘No, it is good. I am always most interested in my passengers.’

‘Where is your home, Hakim?’ I asked.

He studied me for a moment. ‘Not many passengers ask me about my home,’ and he nodded approvingly. ‘I was born in Bombay, a most busy and most beautiful city in India.’

The next moment we reached our cabins. Mama and Papa were shown into one. Ours was just next door. The first thing that hit me was the smell, which was a strange soup of furniture polish like Daisy, our parlour maid, used at home, all mixed up with burnt oil and seaweed.

‘It smells strange,’ said Lily, wrinkling her nose.

‘It will be better once you have let it air for a while,’ said Papa from the doorway. ‘In any case, you’ll soon get used to it.’

The cabin was smaller than I’d expected, and darker. The only light filtered in through a porthole no bigger than the globe in the schoolroom at home. A brass oil lamp hung from a hook in the ceiling. Fixed to one wall was a washstand, while built into the opposite wall were two snug births, one above the other, each hidden behind its own little curtain. A wooden ladder ran from the top bunk to the floor. Against the far wall, below the porthole, was a small leather sofa.

Lily was frowning at the ladder. She was terrified of heights of any sort.

‘Shall I take the top bunk?’

She threw me a relieved smile. ‘Please do.’ She peered round the cabin. ‘But wherever are we going to put all our luggage?’

‘We will have our cabin trunks in with us,’ explained Mama as she joined us. ‘The other trunks will go in the hold and not be seen again until Suez.’ She gave a short laugh. ‘I’m glad crinolines are no longer the fashion. I believe I would have hardly fitted inside the cabins wearing mine.’

I glanced at her dark blue, travelling dress with its neat bustle, and thought she was right, imagining her in the huge birdcage of wire and tape that she used to wear under her dresses. Papa had been relieved when the fashion for crinolines had ended as he said many women had died when their skirt had caught fire, or become trapped in the wheels of a passing carriage.

Ask Paige - Team Assistant

Ask Paige - Team Assistant