PART I of IV

KISHAN CHAND

CHAPTER ONE

Doon Valley, 1905

In the year 1905, at the peak of his profession, a youthful forty-something Kishan Chand Das hit rock bottom in life. If anyone were to have seen him that day—his immaculate, imposing, six-foot physique crumpled into an incoherent, disheveled, sobbing ball—they would never have believed him capable of excellence in any endeavor, let alone acknowledge his exalted position as the king of the Doon Valley.

But no one saw because Munshi Ram allowed no one beyond the reception hall of Radha Vilas.

The Doon Valley, cradled in the foothills of the Himalayas, protected by the mighty rivers Ganga and Yamuna on either side and bounded by the Shivalik mountains in the south, is home to Dehradun. Two decades ago, when Kishan Chand arrived, Dehradun—fertile paddy fields, tea gardens, and lush forests—used to be a sleepy settlement of a few thousand Hindus, Muslims, Parsis, and Christians of European origin. The town, though small, was popular with the British as a depot for municipal revenue collection. It served as the cold-season headquarters for its staff, who in the hot season decamped to the Mussoorie Hills, some twenty miles away and five thousand feet higher.

By now, in 1905, Dehradun boasted a fine Forest Research Institute, thirteen schools with more than a thousand pupils, and a cantonment that housed two battalions of Gurkhas who later, in the Great War of 1914, unwaveringly gave life and limb for the Raj. Das Builders and Engineers Ltd., founded by Shri Kishan Chand Das, was the largest employer in the valley. Kishan Chand—his wealth now at par with many a raja—was an acknowledged community leader who also maintained cordial relations with the British. They valued his business.

In awe of his stature, if locals called him Lalaji, Kishan Chand would laugh and say, “The credit goes to Radha. I would be nothing if not for a promise I made to her long ago.”

Indeed, his destiny had no parallel. He started by designing canals suited to the unique Doon geography and then laid underground pipes that flowed sweet water from the Himalayan foothills of Mussoorie to the valley floor. He expanded the canal network till there were more waterways than roads in Dehradun. As more people migrated to the valley, Kishan Chand parlayed his reputation for brilliance in designing canals to excellence in construction—roads, buildings, barracks, bungalows—till an entire mile on East Canal Road sported Das Company offices and residences for its employees, who repaid Kishan Chand with undivided loyalty.

Kishan Chand’s home sat on two lush acres. The central building blended Haveli architecture—three stories tall; a tree-lined, jasmine-scented inner courtyard that easily held ten charpais; a sizeable sitting room—with a colonial veranda wrapping the entire front façade. A stable, cowshed, and carriage house occupied the back. Large enough to hold a wedding, his house on East Canal Road drew envy and admiration in equal measure.

“If not for my beloved Radha, I would be nothing,” he said.

“It befits a man of his stature to be humble,” they said.

Dehradun became a jewel in the crown of Doon Valley, queen of the Himalayas. Canals provided sustenance to basmati fields and a cool breeze year-round. On roads that ran parallel to waterways, townsfolk strolled with evening camaraderie; tongas transported children to schools and women to bazaars. Horses drank at regularly spaced troughs, flour mills powered by waterfalls dotted the scene, and dhobis washed clothes at designated outlets. People flocked to the valley.

Infrastructure projects were launched to accommodate growth. Das Builders, supervised personally by Kishan Chand, built the railway depot. The first train rolled into Dehradun Station on March 1, 1900. The British celebrated with whiskey in the Whites Only bar on Platform One, and the town felicitated Kishan Chand and feasted at the house on East Canal Road.

Erect, groomed to perfection in a crisp white dhoti and kurta, a gold-bordered sash looped around his left shoulder, wherever Kishan Chand went, his calm, confident stride radiated purpose.

“For Kishan Chand,” they said, “nothing can go wrong.”

CHAPTER TWO

Dehradun, August 24, 1905

That fateful day began like any other.

By seven, bathed and dressed, Kishan Chand had entered the pooja room, sat on the mat, and was already halfway into reciting the forty verses of the Hanuman Chalisa when Radha slid in beside him. She started her routine by singing an ode to Parvati. She undressed a twelve-inch brass statue of the goddess and poured a tablespoon of holy Ganga water that collected in the shallow lotus-shaped bowl beneath. She then lit an incense stick. Kishan Chand inhaled her freshly bathed sandalwood soap presence and slowed his recitation to allow enough time for her to dress the goddess in fresh clothes, put it back on the carved pedestal, and apply red sindoor powder on her forehead where she parted her hair.

They finished together, exhaling om, hands folded in a namaste, heads bowed to end the prayer session.

As they rose, Radha sprinkled droplets of the goddess’s bathwater on him, herself, and the air around them till it was all gone.

“Gandhari has a stomachache. I went to see her,” Radha explained with twinkling eyes.

Kishan Chand feigned severity. “You should not go to the gaushala. What if she kicks you?” Kishan Chand knew Radha visited the cowshed every morning, despite his directives. “You are not your sprightly self these days,” he said, unable to hide his relief, “if I may say so.”

“You worry too much. And you go to see the horses too.” She pulled aside her sari pallu to expose an enlarged stomach. “The baby enjoys going to see the cows with me. See how it is rolling from one side to the other?”

Kishan Chand kissed his palms and then laid them on her belly. “This one is for the baby.” He grinned. “And now this for you.” They hugged for a long minute in the pooja’s private room. And then, arms intertwined, they entered the dining room for breakfast to start the day.

As usual.

She chattered away as he drank the crushed almond and cardamom–flavored milk, ate the potato-stuffed paratha she served hot off the fire, washed it all down with water, and rose to wash his hands.

Before leaving for work, he stole a quick kiss. “Not you—it’s for the baby,” he said before she could object or bring up the problem of prying eyes.

Impossible as it seemed, Kishan Chand loved his wife more every day.

Raised on neighboring farms, he could not remember a time without her. They studied together, played together. He did not know how old he was the first time he took her behind the mango tree, away from parental oversight, and kissed her. She had kissed him back, shyly first, then hungrily.

When he left for college, he said, “You will wait for me, Radha, won’t you?”

“What if that landowner’s son sends a marriage proposal? He follows us around in the fields, looking at me.” Radha’s words teased, but she moved close, eyes brimming with mischief, intertwined her fingers with his, and asked, “Have you seen his haveli, Kishan?”

“I will build you a huge house—bigger than his old-fashioned pile. Besides, he is an illiterate lout; he will bore you to death. And he will not take you sidesaddle on a horse like I do. No. You cannot marry him.” Kishan Chand encircled her waist with his arms, leaned in, and whispered, “It is decided.”

Face buried in his chest, giving tiny kisses, she moved her head side to side, teasing, “No, I can’t wait. No promises.”

“Say yes, or I won’t let go.” Kishan Chand tightened his hold. A tussle ensued. Radha never said yes. But her eyes and lips did. The day he left for college, she cried. He kissed away the tears right in front of her aged parents, who looked away from such shameless lack of self-control but did nothing to stop him.

During Kishan’s college years, Radha’s father had to suffer noisy tantrums when he brought her a marriage proposal.

“Boys change when they go to college,” her mother reasoned. “You are foolish to refuse such a magnificent prospect, waiting for Kishan.”

But Radha would not listen.

Kishan Chand finished the four-year engineering curriculum in three and came back home to claim his bride. Their marriage—a simple ceremony performed right under the mango tree where it all began—befit their meager finances but not their devotion to each other. Contrary to custom, the love match received parental blessing, and following their cue, the priest also pronounced the union propitious.

How was it possible to love her even more today than he already did?

“Munshi Ram will bring your lunch. I have a surprise planned for you,” Radha called from the kitchen, breaking his reverie. She walked with him to the front gate and waved.

At noon, when Munshi Ram came, the surprise was not the one she had planned. “Babuji—come home. Quickly. Bibiji is asking for you. Her water has broken.”

By the time he reached home, the dai and other attending women had already taken Radha into the maternity room. As was customary in those days, he was not allowed in. “It is too late for you to see her now. Do not worry. Bibiji will be fine,’” the midwife said.

Kishan Chand paced outside the room. He knocked on the bolted door, but—as if in answer—a small scream came through. Then short shrieks, periodically punctuated by long silences. It went on for hours.

Unable to help, he pretended the screams, though different from her previous deliveries, sounded normal. The screams grew weaker and weaker till there was complete silence.

Then the definitive cry of a newborn escaped through the door. He sighed with relief.

No. Something was wrong; no joyous sounds came through the door.

“Let me in. Now.” He banged the door till the bolt slid open. “You have a son,” the dai said. She held out a tiny bundle. She had not had time to clean the blood or change the sheets.

Kishan Chand pushed her aside and ran to the bed.

“Radha, say something. Talk to me.” He murmured endearments, kissing hands and face, and clung to the lifeless form. The dai called for help, and Munshi Ram rushed in.

Kishan Chand did not eat; did not sleep; did not allow anyone to move him from her bedside that day.

He did not hold his newborn son.

At night, with some help, Munshi Ram carried Kishan Chand out of the maternity room and put him to bed in his own chambers. Kishan Chand refused to meet anyone, lying sightless, soundless.

In his capacity as a personal manservant to the master of the house and the mistress not being alive, Munshi Ram was forced to take charge of the tragedy. He began rituals for the thirteen days of mourning; proprieties befitting their position had to be followed. Such was the efficiency of the Das retainers that without undue mishap or mayhem, pundits performed poojas; guests were fed and housed. Children were kept busy and away from activities relating to the body, the procession to the cremation grounds, and the cremation itself.

A wet nurse was hired. The baby became pink with health, clenched tiny fists, and opened his eyes.

When he finally emerged, Kishan Chand was man enough to cry in front of all. Matchmakers presented marriage proposals.

“How will you manage, Lalaji?” said women wanting a share of his wealth and youth. “You need a woman’s guidance, or they will rob you blind. How long before the milkman mixes water in the milk? Who is to order the rice, get wheat stocks replenished? And what about this huge kothi? After every monsoon, leaking roofs must be plugged and walls whitewashed. A big household like yours has many expenses.”

Kishan Chand had never needed to know the effort entailed in maintaining Radha Vilas or its large number of residents.

Traditional women paraded daintily and smiled from the safety of a veil. Anglicized women openly tut-tut-ed at his folly of stoicism. Envious men feigned concern.

“Such a loss, and that too at the peak of your manhood. You are young enough to father more sons, and you have money enough to feed a biradari clan.”

“I will not marry again.” Kishan Chand desired no more sons. Including the newborn, he already had four.

“How about a daughter? You have no daughters,” they said.

Kishan Chand poured havan-samagri into the holy fire when pundits indicated. “I have been luckier in love than any man has a right to be. It will fulfill my lifetime of wants. Another marriage would destroy precious memories.”

But among the townsfolk, the debate raged: marry or not?

When he could handle it no more, Kishan Chand retired to his chambers. Only Munshi Ram had permission to enter.

“It is the tenth day since Radha Bibi passed. Why not go to your office today. It will distract you,” said Munshi Ram, desperate to get him out and about.

“I lived for Radha. Why should I go to work? Anyway, the British have betrayed me. Hypocrites! I thought we were partners.”

“Why? What happened?” Munshi Ram was happy to hear him talking.

“Last month, the Imperial Gazetteer announced Curzon’s plan to partition Bengal. I went to see the Laat Sahib. We meet regularly, and I thought him a good man. I said the partition would foment division along religious lines and urged him to use his influence with the viceroy to stop its implementation.” Kishan Chand paced. “Do you know what he said?”

“No. What did he say?” Munshi Ram was afraid to ask, but at least Babuji had stopped holding his head in his hands. Angry was better than lifeless.

“He said, ‘Mr. Das, do what you are good at; leave ruling the country to the British. You Indians do not have the discipline to manage yourselves. If you meddle in my business, there will be consequences to yours.’ Can you believe it? He threatened me. I thought he would help; instead, he parroted government propaganda.”

“What about Manager Sahib?” Munshi Ram pleaded. “He asked to see you.”

“If I go to work, it will be to organize a walkout. So, better for him if I don’t go.”

“Yes—maybe a bit more rest.” Munshi Ram abandoned the topic.

Kishan Chand settled into a deeper funk. Documents requiring attention were sent by the office, but he flung them aside: unopened, unread, unsigned. Munshi Ram gathered them, and the pile grew.

One morning, a classic postal-pink envelope arrived—a telegram. Kishan Chand turned it over and over, afraid of more bad news.

“Who is it from?” asked Munshi Ram.

Kishan Chand, lost in thought, pocketed the paper, patted it secure, but did not reply.

On the fifteenth day of his wife’s death, two days after the pundits permitted travel, Kishan Chand announced he was leaving town.

“My house is yours, so stay as long as you want, but I have to go.”

He gave no directives on what was expected from them or what his plans were. Indeed, Kishan Chand hardly knew himself. All he knew was, without Radha, he could not abide Radha Vilas.

CHAPTER THREE

Allahabad, 1905

Kishan Chand boarded the Dehradun-Allahabad Express by mounting all three steps from the platform to the bogie with one upward swing of his right leg. He walked in, locked the door, and looked around: empty. Not surprising since he had bought every seat—first class was not for whites only; they needed his money— but still a relief. Rajas and nawabs routinely booked entire trains when they wished to avoid the white man, so a compartment to himself was well deserved at such a troublesome time.

The mahogany interior—clean symmetrical lines, padded leather seats, side panels adorned with windows, a pair of cream-colored, operable sash decorating each curtain—soothed his nerves; the coach, designed and built by the American Car & Foundry Company, had been his procurement when Dehradun was connected to Hardwar Junction. His temper improved a tad.

The train whistled its departure. As it picked up speed, feeling safe from the possibility of any human encroachment, Kishan Chand sat and exhaled tension. For the first time since that fateful day when Radha died, the clanging in his brain softened; waves of relief coursed through his body. It was not that his wife’s death had launched additional responsibilities, but her death left a void, a lack of purpose. Why should I awaken every morning? Kishan Chand took out the telegram from his breast pocket and, though he knew it by heart, read:

By the grace of God we are blessed with a girl STOP Mother and child healthy STOP Me ecstatic STOP Visit us if possible STOP Moti Lal Tripathi

Moti Lal, his friend from college, was a lawyer in Allahabad High Court. They kept in touch by announcing births and significant family events, but it had been years since they had met. Every Diwali, greeting cards enclosed in a gift box—sweet mithai, savory pakwans, cashew nuts—were exchanged to convey goodwill.

A daughter …

Moti Lal’s first child was born after many years of marriage. A favorable time for him. How to announce his own misfortune in the face of such joyful news?

A telegram?

Wife dead STOP Self grief-stricken STOP Happy for you STOP Kishan Chand Das

Or, a letter?

Dear friend, Congratulations on your good fortune. I unfortunately must announce …

Ruefully, his inability to pen a meaningful missive had resulted in the trip to Allahabad. Words could not convey joy and devastation in the same breath without sounding false. But a visit—that seemed much easier. In person, he could express joy at Moti Lal’s good fortune while grieving his loss.

And disappear from Dehradun.

On board the train, the morning’s frenzy—packing, gifts, last-minute reservations, horses hurtling—faded. The lull in action deadened his spirit.

Comments

Author Note:

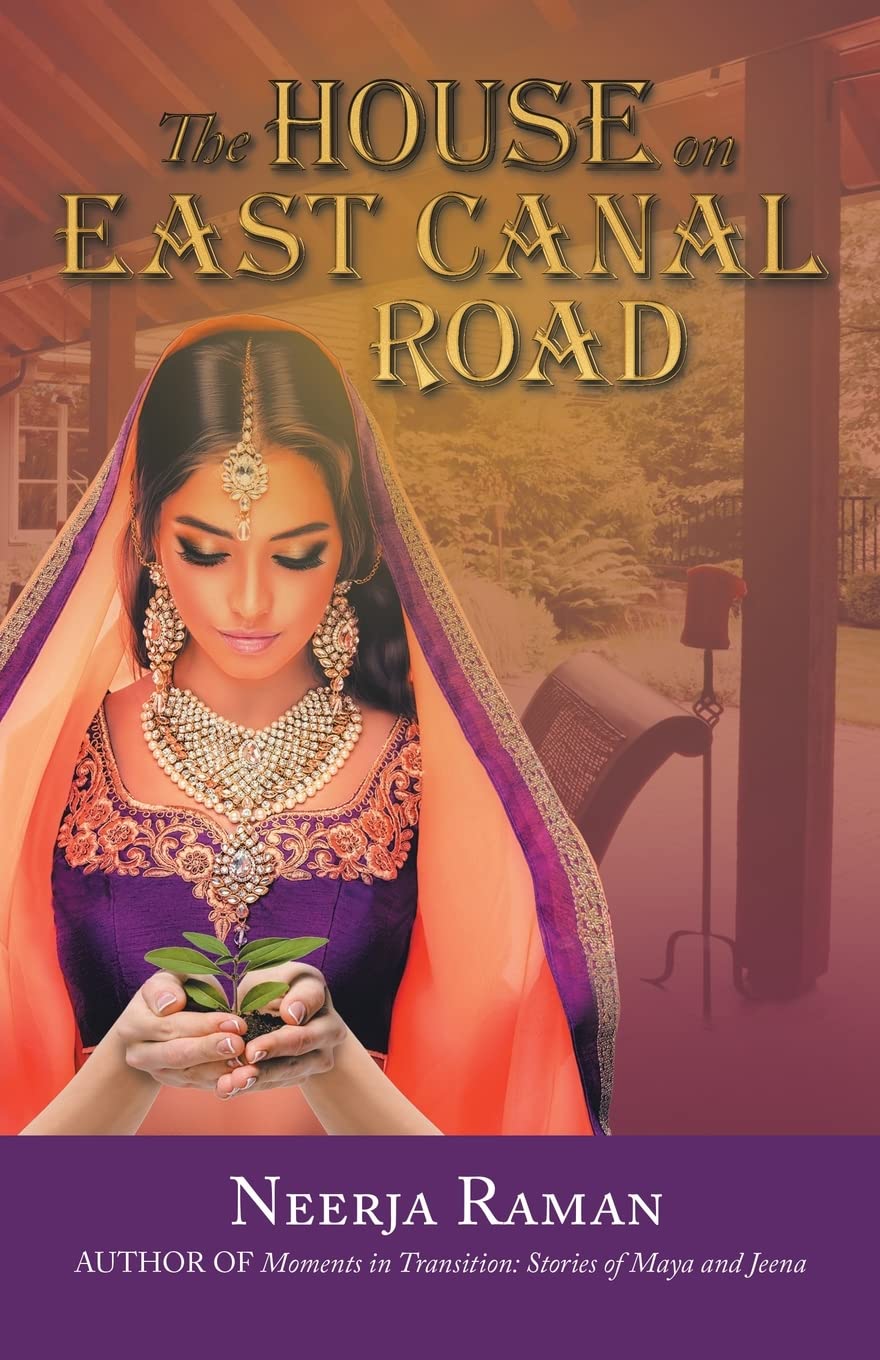

The House on East Canal Road is dedicated to my grandfather. Below, a snippet from the Author's note that inspired me to write the book:

------

One day, when I was young and impressionable, I yanked at the drawer of an ornate writing desk, a family heirloom, and it broke.

"I didn't do it, Papa."

"Yes. I know," he said. "Your Dadaji did."

My grandfather toured on horseback all over Punjab—some parts are now in Pakistan—building canals, and everywhere he went, that desk went with him. It was designed to collapse into three easily reassembled pieces. Only a camel could carry that much weight, so it traveled in a carry-bag intended to accommodate a pacing gait where both legs on one side move together. It protected the animal and the desk. Thus, his precious cargo, a symbol of dignity and authority, withstood vagaries of several dusty journeys without mishap.

-----

My grandfather died before I was born. But his legacy lived on in the house he built for his family.

Neerja Raman