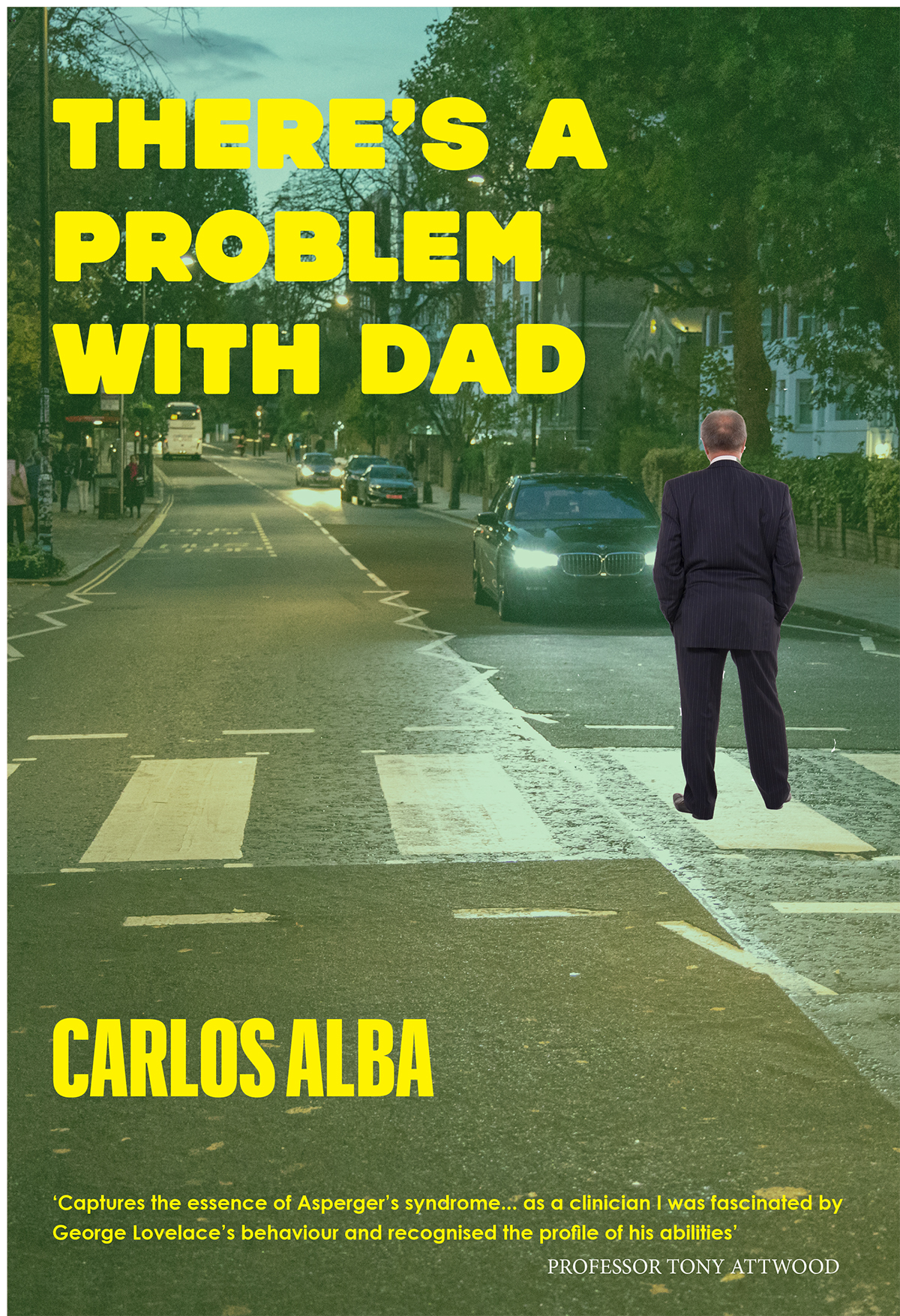

There's a Problem with Dad

Police Scotland, Fettes Avenue, Edinburgh

Roz surveyed the glossy, anti-crime posters on the walls and the jaded faces behind the Perspex screens and remembered vividly the last time she had been in a police station – March 1995, a Saturday, when she should have been seated in the main stand at Murrayfield, feigning interest in Scotland v Ireland. Instead, she was stuck in an interview room at Corstorphine cop shop, trying to explain to a pair of young constables why she’d been caught at the foot of an investment broker’s garden with her knicker elastic stretched around her high heels, pissing all over his seedling rhododendrons.

It was her boyfriend’s fault (the first and last time she’d been out with a fucking rugby player), she told them. He’d filled her full of cheap Chardonnay, which she hated, in a dingy Rose Street pub and then marched off with a gang of his fat necked mates towards the stadium to watch the rugby, which she hated, leaving her trailing cross-legged behind. A mile-and-a-half without a fucking piss break; what was a girl to do, she’d pleaded, flirting with them as best she could in the circumstances, still confident at that age that she had the collateral to carry it off.

And she did. They let her away with the lesser charge of urinating in a public place when she could have been done with the more serious breach of the peace.

She should have been grateful, they told her. An inoffensive, buff envelope dropped behind the door of her flat a fortnight later containing an indictment, allowing her to plead guilty by letter and to pay the £80 fine in monthly instalments of £10, which she did from her student loan. She breathed a sigh of relief, worried that a more serious charge might have put an end to a career in politics before it had even begun. Such naivety: that idea had long since been kicked into touch, to borrow a rugby metaphor. Today she’d plead not guilty, pointing out that the pub had breached her human rights by not having a women’s toilet.

She caught her reflection in a mirrored window that she guessed separated the booking desk from the custody suites and was shocked at how drawn and hunted she looked in her drab, black overcoat that was now a size too big for her. In her twenties and thirties, she might have got away with a dash for the red-eye flight from London the morning after two bottles of wine

and 30 fags, but not now. Everything seemed so uncomplicated then – a baggy jumper and a pen in her hair were all she needed to appear effortlessly cool and desirable. Now it took a morning’s work to avoid her looking like she collected cats.

She had dropped everything following Melvyn’s cryptic, late night phone call and then barely slept, knowing she had to be up by 4 a.m. Her mother had been dead less than three weeks following an ugly illness that culminated in a slow, spiteful end, and now this. If she believed in a god, she might have thought he was trying to punish her for all the human trash she’d put out with the empties over the years.

Melvyn walked over, unthinkingly offering a hand before realising he never shook hands with his sister, patting her gently on the shoulder. Roz was glad she didn’t have a touchy-feely family; she feared that even a moderately forceful hug would see her disappear within his grasp, like sand draining from a bag.

‘Where’s Dad?’ she asked.

‘He’s in an interview room with a couple of detectives.’ She waited for him to expand but there was no more. ‘So, what are they doing?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Have they charged him with anything?’ Melvyn bristled.

‘I said I don’t know.’ ‘I only asked.’

‘I don’t know any more than you do. If I did, I’d have told you.’

Yards away a jaundiced woman with a protruding jawbone conferred loudly with a disinterested desk sergeant through the screen. She held up a hand that was wrapped in a blood encrusted bandage to the officer who was paying minimum wage attention to her garbled tale of casual abuse in the bootleg opiate market as he took a draft from his mug of tea. The woman could have been 30 or 50 with her flyblown, sunken eyes and blackened bombsite for a mouth. Roz had seen similar sights in rehab a dozen times before and she wasn’t shocked. Despite the relentlessness of the woman’s hard-luck story, she still managed to laugh, coarsely and uproariously, at frequent intervals, while the policeman’s face remained deadpan.

Roz decided she could no longer resist the siren call of nicotine. If she were to survive the next day or so, or however long it would take to get this thing sorted, she would have to nourish her addiction, which would have the added benefit of helping to ration contact time with her non-smoking brother.

‘I’m going out for a fag,’ she announced.

Melvyn had arrived in a cab – he didn’t want to bring his car in case someone recognised it in the car park – and he wore jeans and an old fleece he had found at the back of his wardrobe which, he figured, he must have last worn more than 20 years before. In the taxi he had noticed a badge pinned to its breast in support of a workers’ sit in from the 1990s. He remembered the case well; it involved an American company that owned a clothing factory in Kirkcaldy where the machinists had all been sacked for refusing to accept new contracts. Egged on by their union, they refused to leave the building and the newspapers were full of stories about these feisty Scottish women determined to take on their rich Yankee bosses. Melvyn was a trainee at a no- win-no-fee law firm representing the machinists and it was one of the first cases he worked on.

It was his role to interview the women and keep them up to speed on how the case was going, a job none of the more senior lawyers would dirty their hands with. It was still one of the most difficult things he’d ever done. Perhaps it was because he was young and green, but there was more to it than that. He could hardly understand a thing the women said because of their thick Fife accents and he found it hard to communicate with them. His boss kept telling him to form a ‘connection’ with them but, no matter what he tried, it never seemed to work. In truth, he didn’t really know what his boss meant.

In the end the company had to go to court to force the women out. It won, but six months later it closed the factory, claiming demand had plummeted because of all the bad publicity. The only winners were the City lawyers representing the company who were handsomely rewarded for gaining the court order. Melvyn was let go by his boss who claimed they should have won.

The tabloid papers reported that in many cases the women were the only breadwinners in their homes because their husbands had been made redundant from a local coal mine. That was information Melvyn should have gleaned from the women as it could have been an important detail in swinging the case, his boss told him. He figured someone, probably Roz, must have pinned the badge on his fleece for a joke. He pulled it off and threw it out the window of the taxi.

Roz returned smelling of cigarette smoke and Chanel No5.

‘Tell me again what happened,’ she demanded. ‘I’m still not entirely clear why we’re here.’

He was not minded to tell his sister anything, even the little he did know. He had only just managed to quiet the raging voice inside his head urging him to throttle her. It was at her suggestion that he had invited their father to his company’s ball in the first place. Left to his own devices he would never have placed him in such an unpredictable environment, less than a month after their mother’s death. Roz knew full well what he was like. If only he had trusted his own judgment and resisted her righteous pleadings, none of this would have happened.

‘I’ve told you all I know. A complaint has been made against him.’

Of course, he wouldn’t throttle her. He wouldn’t even tell her he wanted to throttle her. The worst he would do would be to breathe heavily as a sign of his exasperation. Externally he would be as calm as a statue while his stomach was a spin cycle of resentment.

‘Do you know any more about what the woman is claiming?’ ‘The woman’s 17,’ he shot back.

‘That’s old enough to know what she was doing. I remember some of the things I got up to when I was 17.’

‘Not everyone’s like you.’

Suppressing murderous rage toward his sister was, of course, preferable to the guilt he felt for having brought everyone to this pass in the first place, not that he could ever reveal the truth. How could he possibly tell them they need not be here at all, if only he had had the guts to stand up to his father-in-law? It was true that, if George had been at home, safely away from other people, this incident – alleged incident – would never have happened. That much was certain, and it was something he would cling to as vindication, come what may. Was it his lack of judgement or understanding that had got the better of him and allowed the situation to spiral out of his control? He’d been outmanoeuvred by Robert, the wily old bastard, who had glided into his office with the sort of portentous flourish that told Melvyn he needed to have his wits about him.

‘Something’s come up, old man,’ he declared in that annoying, I know something you don’t way which he revelled in. ‘I think you ought to know that your father has caused something of an upset.’

Melvyn said nothing, while Robert set out his wares with the verve of a showman.

‘Now, before I proceed, I should say there’s no reason why this needs to go any further. No one wants a scandal, least of all the girl’s parents, and we all agree it’s in everyone’s interests for it to be contained.’

So typical of Robert to spot an opportunity to profit from a ‘scandal’, Melvyn thought. It was meat and drink to the old man, to put himself at the heart of the matter and engineer it so that Melvyn would end up owing him for sorting it out. He’d been outmanoeuvred by him so many times in the past and he still couldn’t work out how. He was so much quicker and smarter than Robert – he’d demonstrated that in business many times over and so, in situations like this, he should have been able to run rings around him. But it never quite worked out like that. Well, not this time, old man, he’d resolved. Not this fucking time.

‘If the girl’s complaint is genuine, she should go to the police,’ Melvyn stated with a dry calmness.

Robert held Melvyn’s gaze for a couple of moments, wearing a deniable smile. ‘Now hold on, no one’s mentioned the police,’ he said coyly.

‘Why not? What is it that her parents are afraid of?’

That was clever, he was pleased with that at the time; putting the old man on the back foot, making him answer the questions for a change.

‘Don’t be ridiculous, Melvyn. You know perfectly well that’s not the issue.’

Of course, he didn’t expect Robert to answer any questions, he was far too elusive for that.

‘No, Robert, I don’t know what the issue is. From my perspective, it is perfectly clear. If someone is making a complaint of this nature, then the normal thing is for them to go to the police. Wouldn’t you say?’

Robert shook his head, projecting that image of apparent incomprehension he normally reserved for board meetings. Of course, Melvyn never expected the old man to actually go ahead. This sort of thing was always handled ‘in-house’, in an organisation like theirs. Robert was full of stories about how he had smoothed things over, calmed tensions, called on his impeccable connections to protect the reputation of the firm over the years. But not on this occasion. Once again Melvyn had been well and truly wrong footed.

A man and a woman emerged from the door next to the booking desk and made straight for Roz and Melvyn. The woman asked if they were relatives of Mr Lovelace, which made Roz think they had been watched from behind the mirrored window. Melvyn made a typically officious attempt to introduce himself, accompanied by one of his weighty handshakes. The man introduced them as Detective Sergeant something and Detective Sergeant something else – for a journalist, Roz was hopeless at registering names at the best of times, but her mind was suddenly numbed by the realisation that the situation was real.

He wore an attention-grabbing shiny grey suit whose impact was nevertheless compromised by his even more striking bottled winter tan and recently whitened teeth. The woman was dressed more casually and had the kind of androgynous look Roz guessed was still beneficial for a woman to succeed in this line of work.

The male detective sergeant said they had suspended questioning of Mr Lovelace for the time being but that they would require him to return, later in the afternoon, accompanied by his lawyer. If he didn’t have access to a solicitor, then one could be provided.

‘Why does he need a lawyer?’ Melvyn asked urgently.

‘We think it would be in your father’s best interests if he were to have a solicitor present,’ the female detective said.

‘Is that strictly necessary, Detective Sergeant? I’m sure we can clear this up now without having to take up any more of your time.’

Roz muffled a sigh and cast her eyes skyward.

‘We think it would be in your father’s best interests if he were to have a solicitor present,’ the policewoman repeated, taking a step forward as though to reinforce the importance of what she was about to ask.

‘Does your father suffer from any conditions that we should know about?’ Roz and Melvyn exchanged glances.

‘What do you mean?’ he asked.

‘Does he suffer, or has be ever suffered, from any mental health issues?’

‘No, he never has,’ Melvyn stated emphatically. ‘Is that a question that you ask of all your interviewees?’

‘No, it’s not, sir – it’s just that if there are any circumstances relevant to your father’s situation that we should know about before questioning him, then that is clearly something that should be volunteered sooner rather than later.’

They all stood in silence for a few moments.

‘So, you’re clear there’s nothing we should know about?’ the detective said.

Roz moved forward slightly as though she was about to say something, but her brother took hold of her arm and pulled her back.

‘We’re absolutely sure, Detective Sergeant, there’s nothing we can tell you. As you can see, having met our father, he is as sane as you or me.’

The pair watched as the detectives disappeared back through the door. They returned a couple of moments later with George, who was dressed in his standard uniform of blue blazer with pressed slacks and tan moccasins polished to a high shine. He greeted them with a grin that Roz feared the police might mistake for defiance, but they didn’t know him the way she did.

Smiling was simply his way of letting them know he would not let a minor setback like this defeat him. She walked forward and took hold of his arm.

‘How are you, Dad? Are you ok?’ she asked.

‘Oh, nothing that six numbers on the lottery wouldn’t put right,’ he replied with a grin.

When they were children it had been eight score draws on the football pools. When Roz was little it gave her a warm sense of reassurance, knowing that things were normal, but now it sounded ridiculously out of place. She had been desperate to see him but now they were together she didn’t know how to behave or what to say. Despite his hail fellow bravado, there was no mistaking that he looked lost.

‘How are you, Roz? You look terrible,’ he said, suddenly displaying that he hadn’t lost his uncanny ability to defy expectation.

‘Thanks, Dad, kind and supportive of you to say so,’ she snapped back.

She felt an immediate rush of anger combined with guilt that only her father could provoke. His comment was typically insensitive and hurtful and yet, of all the things he could be accused of, lack of support was not one of them. George may have had his faults, but as a father he was always dependable and loyal to a fault. There was not a ballet performance, sports day, parents’ evening or gang show where he had not stood by dutifully, always at the front of the queue, always first to buy the tickets, always front row centre. He was the one who checked her

homework, prepared her packed lunches, drove her to school discos, taught her to drive, helped her to fill out her university application forms, while for the most part her mother lay in a darkened room with an ever-present bottle of sleeping pills.

Roz knew what a truculent and unpleasant teenager she had been and how her behaviour must have challenged both of her parents to the limits of their endurance. But she was also aware that whatever she did or whoever she became, George would be there to watch over her and to pick up the pieces when she fell apart. He’d never been the most demonstrative parent – she couldn’t remember a hug or an expression of love – but he was always the one she could rely on; the one who appeared, rigid and mute, at her hospital bedside when, at seventeen, she had an abortion, who paid off her overdrafts and visited her in rehab for six weeks without missing a single day.