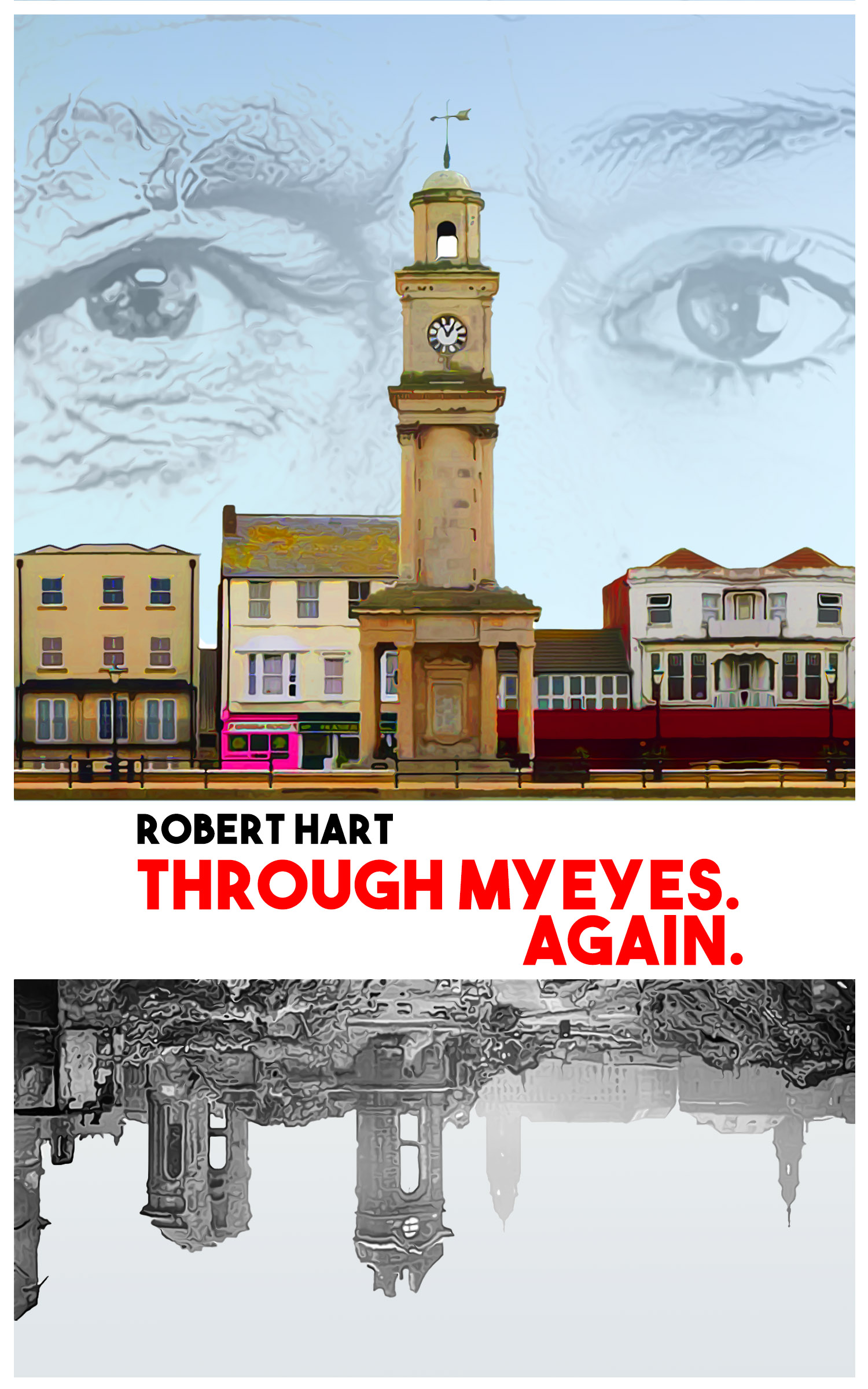

Through my Eyes. Again.

If you want to read their other submissions, please click the links.

Chapter 1

Saturday, 13th October 1962

He was standing on the far side of the railway line, the untrimmed growth that grazed the fence hiding him from view. The public footpath slanted on up the hill towards the woods at the crest. Was this the place? he thought. Or should he go to the greater privacy of the woods? But the climb would be in full view …

No, here would have to do.

If he delayed, he feared he would lose his resolve. Shrugging off his coat, he retrieved the drawing compass from his school bag, its newly sharpened point glinting in the thin October sunlight. No knife, so no single smooth slice to a fast fade; it would have to be multiple punctures, the extra pain his reward.

He dropped his satchel, the strap slithering down his arm and sank back into the matted grass edging the scrub. The thick wool of the school jersey moved easily up his arm. The diagrams of the wrist and forearm in his mother’s anatomy text were clear in his mind – the arteries boldly drawn in carmine ink. The needle-like point of the compass teased his skin and he wondered how many punctures he would need. Would he need to pierce both arms? Possibly. He slid his right jersey sleeve up past the elbow as well.

He would probably cry out with each plunge and would need the camouflage of a passing train. A strange sense of detachment enveloped him and his mind drifted until he heard the distant clatter of an approaching train, its low speed and loud clanking marking it as a goods train – perfect.

The point poised over the first chosen spot and the clamour grew. Just a bit closer… he pressed it down slowly, ready for the first swift puncture.

*

I jerked upright in surprise, pricking my skin with the compass in my hands. A bead of blood formed on my wrist and instinctively I leaned forward to lick it but stopped in shock when I realised my wrist … was not mine: there was no sign of the greying hair and age-marred skin.

And yet … it was the wrist of this body: it flexed when I told it to.

I felt my tongue drag across the skin and the sting of saliva in the tiny puncture. The blood left a smear in which a smaller droplet formed. I rotated my hands, revealing fresh, pale skin with none of the blotches and well-known scars that came from seventy years of living.

Above me, I saw the hill crowned with woodland and the footpath that climbed upwards, only to lose itself in the autumnal russets and yellows. From deep in my brain, surging to the surface came the memory: the hill behind my junior school back in England.

I sat there, baffled. My last recollection was relaxing quietly, half a world away with a glass of Australian Shiraz beside me. I must have dozed off. But no previous dream had ever been this sharply drawn; each strand of yellowing grass crushed under my feet was executed in exquisite perfection. What had stirred this distant memory to surface with such preternatural detail? And that thought brought me to a halt: whilst asleep, I was critiquing my dream?

I glanced around, expecting the images to spiral away, but nothing happened. There was only the sound of the whispering breeze, gradually chilling my bare arms and legs. Minutes passed, as another train slipped into my world, building to a crescendo before rushing away.

I surveyed my body – skinny legs sticking out of grey corduroy shorts, grey knee-length socks, black lace-up shoes, glasses on my face. Such a youthful body, that of my youth – and it had been about to spike its arteries. The dark emotions of my younger self flooded me in a boiling tide. My head jerked up and I felt tears run down my cheeks. The bitter memories of these bleak times flooded through me– the school bullies, my father’s beatings, my impotent raging and my loneliness. With my eyes closed, I took a stuttering breath. The rawness of these teenage emotions was agonisingly sharp for a seventy-year-old.

And I knew when I was as well as where: my first contemplation of suicide, aged twelve years.

But I had only thought about it and that contemplation had happened on the other side of these railway tracks. Memory, dream, or nightmare, this was different.

I supposed I could have sat there by the railway line and waited to see what happened, but I was starting to feel cold: time to go. If this were a dream, it could end somewhere else just as well as here.

I was still clutching the compass, so I opened my school satchel and dropped it in, pulled my jumper sleeves down to my wrists, donned the blue school mackintosh and cap and set off, back across the railway line and through the village to the bus stop. I was hoping for a number seven bus, which would take me within a couple of hundred yards of my house, but what came was a number six, which meant a mile walk and a steep climb home. I sighed and went up to the top deck.

The conductor eventually followed me. “Tickets please!” Her lilting West Indian accent was still a novelty in the rural Kent of 1962.

For a moment, I froze and the conductor’s sunny smile morphed towards a glower, but my twelve-year-old memories served up the knowledge of my season ticket in its leather case, firmly attached by a cord to a button in my left-hand coat pocket. I dragged it out and the smile returned as she moved on.

Shoving away the season ticket, I wondered what else I had with me. My pockets turned up only fluff and a handkerchief, so I opened my school bag: a French text, a Latin text, Caesar’s De Bello Gallico, several exercise books. Opening one of these revealed my awful handwriting. I felt my stomach clench – my father goes wild about this.

Goes wild?

My twelve-year-old brain was telling me he would be waiting for me at home, ready to thrash me for even an imagined transgression. But twenty-five years ago, I had insisted on viewing my father in his coffin: I had to see his corpse to know it was finished.

Memory was a confusing melange.

I dived back into the bag finding the Horse and his Boy, my favourite from the Narnia series. I escaped into that simpler world for the rest of the journey, trying to shed some of the turmoil I was feeling.

I kept an eye on the passing countryside and my twelve-year-old brain warned me to pack up and head downstairs for my stop at the foot of Mickleburgh Hill. Trudging up the hill, my satchel banged annoyingly against my thigh until my twelve-year-old brain told me to hook the strap over the opposite shoulder. After the climb, the road flattened out before I turned down my street.

About halfway to our house, a boy was sitting on a low wall, idly kicking his heels into the bricks. He glanced up once as I approached and then went on staring at his feet as they banged on the wall.

I stopped – anything to delay the arrival home. “You are new around here,” I said, realising I had never seen him before; he wasn’t part of my memories at all.

His eyes narrowed quizzically. The feet stopped kicking. He stared up at me with wide, almost black eyes. “Neu…new…Ja!”

He was speaking … German. I had learned the language in senior school.

“D…umm.” I had nearly replied in German – but my twelve-year-old self wasn’t supposed to know his language. “Um…who are you?” I spoke slowly as I suspected he spoke very little English.

He gave me an unblinking stare for a second or so and then jumped off the wall and headed rapidly back down the road in the direction I had come. I almost called after him, but I couldn’t think what to say in English that he might understand. I watched him turning the corner at the end of the road without a backward glance. This was becoming quite strange. I had never met – or even known of – a German-speaking boy around here. It seemed like the world of my childhood but at the same time, it wasn’t. The weird nature of this dream was rising. What would I find at home – my mother, father and sister or some complete strangers who would throw me back on the street? Was this reality or a dream?

The kitchen lights were on and I walked warily towards the back door. A head with a long pigtail appeared in the window and turned, glancing at me. It was my bossy older sister as I remembered her as a teenager. I saw her dismissive sniff of recognition as I climbed the two steps to the back door.

My father was seated at the kitchen table, so young and such a malevolent presence as he loomed towards me.

“Why are you so late?" He snapped the question, voice coiled with menace.

Our final physical confrontation, one Christmas day when I was fifteen, crashed into my consciousness. I had silently urged him to just touch me and had gleefully imagined I would hammer him, but after a few nose-to-nose seconds he had turned away for reasons I still could not fathom.

But now? Now, I was too small to do that. All the angst and anguish that drove my afternoon’s decision flared through my brain, swamping any control my seventy-year-old self tried to impose. Suddenly I was crying impotently, fleeing through the house pursued by my father’s yells up the stairs to my bedroom. Slamming the door behind me I threw myself onto my bed and sobbed.

It was dark when the bedroom door opened and light from the landing crept in, waking me. I lay still. The slight hint of rose scent and swish of a skirt told me it was my mother. I felt her hand lightly touch my shoulder.

I must have flinched, but I remained curled around my satchel.

“Will, do you want to come down for supper?” My mother asked, softly.

I shook my head.

“Shall I bring you something here, then?”

My stomach lurched and, again, I shook my head.

After a few seconds, I felt her hand leaving my shoulder and with the same faint swish, she left. The room descended into darkness as she closed the door and a terrible fear claimed me. I simply could not go through my childhood again. Even with a seventy-year-old perched on my shoulder, I couldn’t do it. I would make sure I had a knife next time.

But…was there a way back from here? If this were a dream – what would happen if I went to sleep – would I wake up from my slumber, reach out and find that glass of Shiraz? If I killed myself here, would I wake there? Had I had a heart attack and died back in my old world – and what did that mean if I killed myself here? What was the importance of the differences between what I remembered and what I saw in this world? My brain swirled with questions that had no answer.

Lying there, I became increasingly uncomfortable, so I crept over and cracked open the door. I heard muffled voices from downstairs. I took advantage of the relative quiet and got ready for bed. I pulled the covers over me and finally drifted off to sleep.

When I woke, I glanced round at my childhood bedroom. No glass of Shiraz for me – I hadn’t gone back. I lay in bed, immobilised by my crushed hope and this truly strange situation.

I heard my parents heading out for early communion. The front door closed, and the sound of wheels crunching across the gravel drive came to my ears. I decided to make my escape, to find time and space to think. Dressing quickly, I scurried downstairs where my sister was preparing breakfast. I grabbed a couple of slices of bread, slapped on some lime marmalade, slipped an apple into my pocket…

My sister walked back into the kitchen. “Hey! What are you doing?”

“I’m going out. I won’t be back until after lunch. Bye!” And I flew out of the door, down the garden, across the back fence and into the field. Would my childhood sanctuary be here in this world?

The marmalade sandwich was a bit grubby from its encounter with the fence, but I was starving, so I ate as I walked down the field towards the overgrown garden of the derelict house at its end.

This was my private escape – specifically the massive cedar tree. I could lie back and hide, high in its enfolding arms, invisible from below. With considerable relief, I saw its top branches rising above the other trees in the garden. I clambered over the rickety fence and pushed through the overgrown shrubs to the tree. The cedar was so big and spread so wide that, under its shading arms, nothing could grow through the thick carpet of old needles.

I wiped my slightly sticky fingers in the long, dewy grass at the edge of its shade and walked in beneath it. There was only one way into the tree, and it required some acrobatics. I reached up and grabbed the lowest branch in both hands, swinging my feet up. I scrambled round the cold, dark bark and started the climb.

I was reaching for the last handhold before the fork when a head poked out just above me. This was so startling that I almost fell, waving my wildly grasping hand to regain my balance; another clasped it, placing mine safely on the branch.

“Vorsicht.” (Careful.) It was the German boy. Those large, dark eyes stared down at me. For a few seconds, our eyes locked together in surprise and then I hauled myself up. We sat in the fork, each leaning back against a spreading branch, staring at one another.

He was the same height as me but slender, wearing long, grey trousers and a baggy blue jumper over a grey shirt. His hair was longer than my short back and sides. Mine, however, was blandly mouse-brown whilst his was black and glossy, matching his eyes. His features were delicate and his skin quite pale.

After long seconds of mutual examination, he flicked the long fringe out of his eyes and tapped his chest. “Col.”

Oh, my god, he’s completely different – but in this world is this my friend, Colin – Col? My Col was English, well half English, half Canadian. In this dream, this world, Col was German? He was not at all like my Colin, who had been (or perhaps is?) blond-haired and blue-eyed.

Bewildered, I tapped my chest. “William…Will.”

“Ach so! Willi!” He smiled. “Wo wohnst du?” He shook his head when I didn’t respond. “Wo ist dein Haus?” He wanted to know where I lived. I was trying hard to appear uncomprehending, as my brain was spinning around this huge anomaly.

“House?”

“Ja. Dein…you…Haus?”

“Oh.” I waved vaguely through the cedar branches to where part of our roof was visible. “Um ... you?” I was still not thinking very clearly.

He pointed in the opposite direction, across some vacant land to houses along Sea View Road. I remembered where my Col lived, and it wasn’t in Sea View Road. Col was eyeing me speculatively as all this bounced around inside my head.

“You are new here!” I eventually said, in a somewhat accusatory tone as if it was his fault that he wasn’t my Colin.

“New…here?" he said, pronouncing the words ponderously, testing them for their meaning. “Yes…zwei Wochen…two…” he held up two fingers and then shrugged, lost for the right word.

I paused, as my brain started working again. I held up seven fingers. “Week?”

He counted my fingers. “Ja, Woche…aber zwei…two.” He held up seven fingers, twice.

I nodded, “Week is Woche!” carefully mispronouncing it Wocke.

“Ja – aber Woche, Woche!” He slowly emphasised the German ‘ch’ sound which didn’t exist in English.

“Woche, Woche,” I copied and then said “Week.”

“Veek.” I smiled and corrected him, making much of the shape of the lips for the ‘w’ sound, which didn’t exist in German.

“Veek!” Again, I smiled at him, shaking my head.

We leaned back against the tree branches, appraising one another – and I heard my father’s voice in the distance. He knew I used the overgrown garden as a sanctuary.

“William! William! Where are you?”

I leaned across and clamped my hand over Col’s mouth. “Shh!” I whispered.

Col’s eyes stared into mine over my hand. After a moment, he nodded and then, gently but firmly, pulled my hand from his face. He must have felt the tremor in it and our eyes locked as he recognised my fear.

We sat in silence as my father searched the garden below, calling out for me. After a few minutes, he swore loudly and headed back to the house. Moving carefully in the tree, we watched him climb back over the fence and walk quickly across the field.

Comments

Well done

I love the premise for this story. You do a good job of showing the protagonist's confusion when he arrives in his young body. I found the idea of young and old minds sharing the one head interesting. I'd hope that reading on would provide some supernatural explaination, or does it all turn out to be a dream? The 70 year old racing to the bedroom to cry threw me. Not sure if both minds work at once or one at a time. The schizophrenic feel was intriguing.