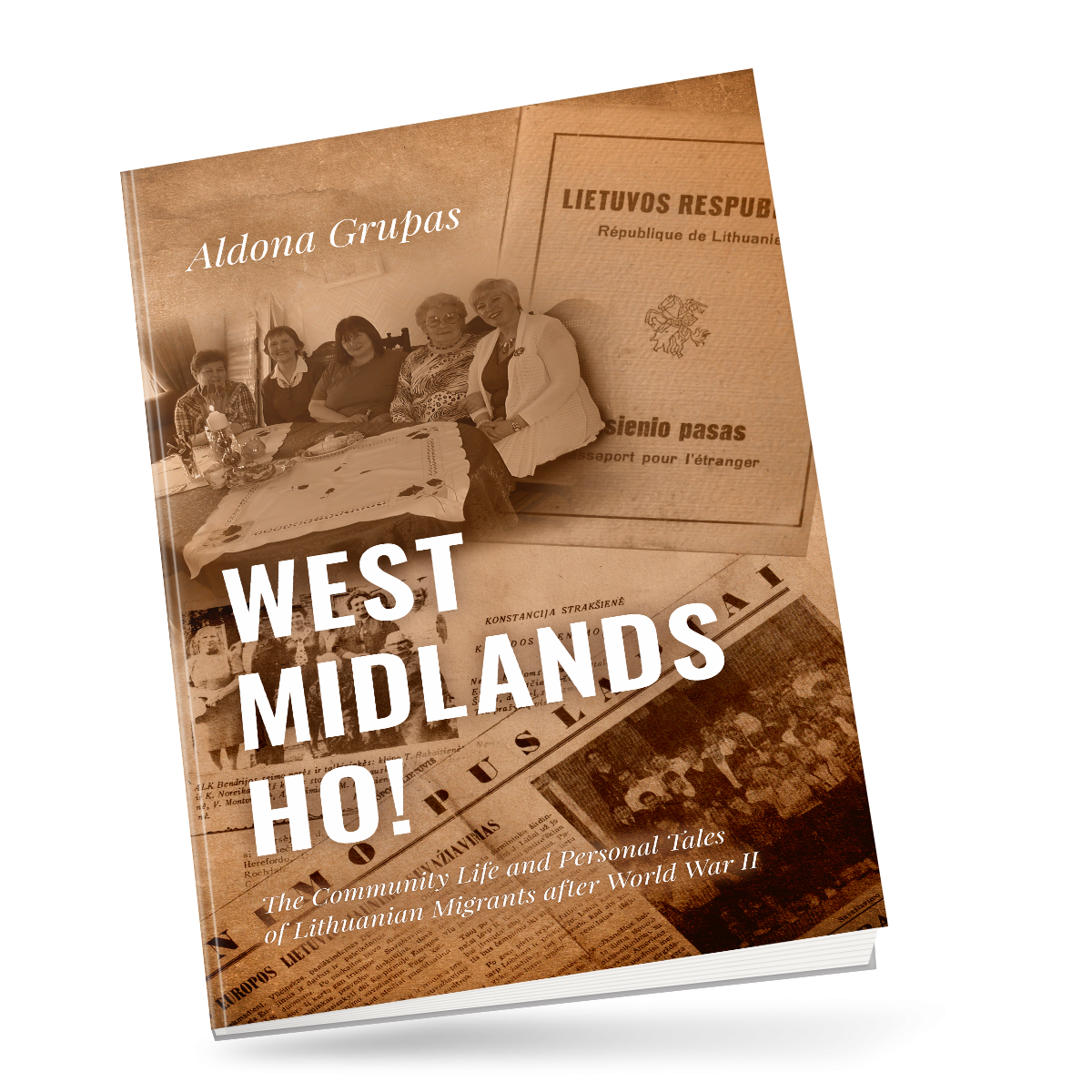

West Midlands HO!

WEST MIDLANDS HO!

Acknowledgements

Many people provided me with help and inspiration in creating the original version of this book, on which this new edition is based. I would like to thank them all for their contributions, which included research, brainstorming, editing and sharing personal perspectives. The original team included Audrone Lamb, Eugenij Soulyga and Connie Van Chorn. Thank you for your support and encouragement.

In particular, I am grateful to the members of the Lithuanian community who agreed to tell their life stories and those of family members who migrated to the West Midlands after World War II. Among them is Gene Ivanauskas, a central figure in the Lithuanian community of Wolverhampton, who provided much of the original inspiration for this project. As a first-generation migrant from the home country, she shared invaluable information on the experience of migrating to England in the post-war period. Another first-generation migrant was Kunigunda Gough (née Kaminskaitė), who provided her own particular perspective, having arrived in England from Germany as a small child. I am also deeply indebted to three second-generation migrants: Terese Irena Macys Russell, Gražina Lockley (née Narbutaitė) and John Petkevičius. This book could never have happened without their kind assistance.

I am indebted to several authors and historians for background information, including the scholar Kazimieras Barėnas, who documented the activities of Britain’s main Lithuanian association over many years. I also learned a great deal from Emily Gilbert, whose book on Baltic refugees is post-war Britain was invaluable in tracing historical developments.

I also received useful pointers from the staff at the Wolverhampton City Archives and the archives at the Library of Birmingham. Their help is much appreciated. The first edition of this book would never have been produced without support from the Heritage Lottery Fund. I thank that organisation’s staff for their advice and support.

Finally, I would like to thank freelance editor David Stanford for helping me to produce this new edition, complete with its many additions and revisions.

Preface to the New Edition

This book, titled West Midlands Ho!, is a revised and updated edition of a book published in 2014 under the title Lithuanian Community in the West Midlands after the Second World War (1947–2012).

I produced the original book with the help of a wide range of people, mostly members of the Lithuanian community in the West Midlands. The focus was on the personal tales of refugee families who had settled in this corner of England after World War II. In addition, I provided some historical information on the Lithuanian community as a whole, including its social and cultural activities over several decades.

That book was well received within the community, with many readers expressing their appreciation for the window it provided on the early days of the post-war refugee community. I was also pleased with this accomplishment, happily donating copies to the Wolverhampton City Archives, the Library of Birmingham and the Lithuanian Embassy in London. I uploaded the book to Amazon, thus making it available to a wider audience.

However, since that time, I have come to see various ways in which that first edition could be improved. For one thing, the English was not always great, with room for improvement in terms of grammar and vocabulary. In addition, while the personal tales provided by community members were very engaging, I had done little to introduce the interviewees to readers, nor to explain my interview methodology. Also, there was little background material to explain those historical events that resulted in the wave of post-war refugees arriving in Britain, nor their reasons for remaining here.

Finally, the information on local community activities was drawn mainly from one source, a book by renowned historian Kazimieras Barėnas. I perhaps relied too heavily on this source, missing the opportunity to provide my own summary of events in a readable format.

Clearly, there was some scope for improvement, and by 2019, I began to wonder about issuing a new-and-improved edition. I had recently gained some success with my autobiographical book, Nurse, Give me a Pill for Death, due in part to my collaboration with freelance editor David Stanford. Since we had worked so well together, I contacted David again to discuss improvements to my book on refugees in the West Midlands. By early 2020, we were hard at work on the new edition, agreeing on the punchier title West Midlands Ho! – a reference to the “Westard Ho!” resettlement programme for European refugees after World War II. After all, it was this scheme that had brought so many Lithuanians to Britain in the wake of the war.

We set about making changes to the text, tidying up the English, providing more historical background, explaining the origins of the project and describing my methodology. I also gave a little more background on those community members who had provided personal reminiscences, and included more quotes from the original interviews that I conducted with them back in 2012. Luckily, I still had the original audio and video recordings, and the inclusion of more quotes from these sources gave more depth and authenticity to the text.

Finally, I cut the community-related material sourced from Kazimieras Barėnas to the bare minimum. In its place, I decided to end the book with a few community-related comments in my own words, based on the points raised by my five interviewees.

However, the book by Barėnas contains a wealth of detailed information, and since it may prove useful to researchers in future, I hope that somebody might translate it into English. The details of his book now appear in the brief Bibliography at the back of this new edition.

My aim in making these various changes was to provide a revised edition that would be both informative and highly readable, thereby appealing to a wider audience.

A note on names

It is probably worthwhile mentioning the approach I have taken regarding names in this new edition. Some of the key people mentioned in this book have names that are a mix of English and Lithuanian, often due to their having mixed marriages. Where a woman has married an Englishman, I have referred to her mostly using her married (English) surname, as this is the name by which she is currently known. This applies, for example, to Gražina Lockley (née Narbutaitė) and Kunigunda Gough (née Kaminskaitė). Terese Irena Macys Russell has preserved her Lithuanian family name (Macys) along with her English husband’s surname.

Meanwhile, two people – John Petkevičius and Gene Ivanauskas – have been referred to throughout the book by their “English” first names, rather than the Lithuanian versions “Jonas” and “Genute”. The adoption of such English first names is a common practice within the community for the sake of convenience, part of the process of integration. Again, I have mostly used the Anglicized versions in this book as this is how they are currently known to many people.

Finally, those familiar with Lithuanian names will notice that Gene does not follow the Lithuanian tradition of applying a feminine “-iene” ending to her married surname. Rather than using “Ivanauskiene”, she uses the same masculine form as her husband: “Ivanauskas”. Once more, this seems to be a matter of convenience, bearing in mind her integration into the norms of British society. I have followed Gene’s lead on this point, using “Ivanauskas” throughout the book.

Introduction

My interest in the Lithuanian community in the West Midlands stems in part from my own identity as a member of that group. Compared to many others, I am a late-comer, having arrived in 2005, while others have migrant roots dating back to the 1940s. In addition, I am a first-generation migrant to England, while many others were born here, being the children or grandchildren of refugees. Even so, we have much in common.

I was born in Latvia, as part of the Lithuanian community there. In fact, my ancestors were prominent members of Riga’s Lithuanian community, having been exiled from their homeland. As a girl, I dreamed of travelling to Lithuania, and once I was old enough, I made that journey. From an early age, this sense of national identity was very strong in me, and it continues to play a central role in my sense of self and my relations with others.

My journey didn’t stop there, of course. After qualifying as a nurse in Lithuania, I set my sights further afield. Together with my husband, a Lithuanian doctor, I began to plan a new life in England. After much preparation, including English lessons and job applications, we finally made the journey. I was full of hope and high expectations.

However, on arrival in London, I received a number of shocks. For one thing, I couldn’t understand what anyone was saying. “What language are they speaking?” I wondered, as I strained to make sense of the local people. It soon dawned on me that England was home to a wide range of different people, originating from every corner of the globe, each speaking their own variation of the English language. As I travelled north for my first job, the problem was compounded by English regional dialects, and it took me some time to learn to communicate with my colleagues and patients.

I was also shocked to discover that my professional skills as a nurse were not automatically recognized. I spent a long time as a care assistant before obtaining authorization to work as a qualified nurse in the UK. Even then, it took ages to find a real nursing job. Meanwhile, some of the staff and managers with whom I worked seemed less than welcoming of migrant workers. This was partly due to language barriers, as well as differences in professional practice. In some cases, however, it seemed I was being discriminated against merely for being foreign.

I have written about my experiences in another book, Nurse, Give me a Pill for Death, so I won’t go into too much detail here. However, it’s worth mentioning that there were plenty of challenges to be overcome before my husband and I felt properly settled in England.

For this reason, I have a great deal of empathy with other migrants who have made difficult journeys and struggled to put down roots in a foreign land. In particular, as a long-time resident of Wolverhampton, I am fascinated by the experiences of other Lithuanians in the West Midlands. I enjoy listening to their life stories and those of family members, learning what motivated them, what obstacles life threw their way, and how they surmounted those obstacles. I’m continually inspired by the efforts they have made to foster a sense of community, while keeping alive their own Lithuanian culture and traditions.

It seems natural, therefore, that I should want to record the life stories of these people, as well as the efforts they have made to establish and maintain a living community. This book is a result of that impulse.

The origins of the project

The idea of writing a book on this topic came to me in 2011, during a conversation with Anna Cielecka-Gibson from the Midlands Polish Community Association. Anna showed me a book that the association had been working on, telling the stories of second-generation Polish migrants in the area. It was an oral-history project, presenting interviews with dozens of people of Polish origin, showing their experiences as members of a migrant community within England. I was fascinated by this project, with its focus on personal histories.

It occurred to me that a similar book could be written about the Lithuanian community of the West Midlands, showing how they moved to England after World War II, building new lives and raising families. I thought I might be well placed to conduct such a project, bearing in mind my links with this community. The book on Polish migrants had been funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, and I wondered if I might receive similar funding.

I met with some consultants from the Heritage Fund and told them my vision. They said that it was a good idea, and it might receive funding, so long as it hadn’t been done before. They checked the archives at the Library of Birmingham, seeking existing materials on the Lithuanian community, while I did the same at the Wolverhampton City Archives. We found very few materials, aside from a few newspaper articles.

I learned that very few books had been written on the subject of Lithuanian migrants to Britain, and most of them were in the Lithuanian language. In 1978, the historian Kazimieras Barėnas published a book called Britanijos Lietuvivi, 1947–1973 (which translates as Lithuanians in Britain, 1947–1973). This told the story of the main community organization for Lithuanian migrants, the Lithuanian Association in Great Britain, and it contained some material on the West Midlands. However, there was little space given to personal narratives, and it had not yet been translated into English.

Based on this apparent gap in the existing literature, the people from the Heritage Fund agreed to provide funding for my book project.

My idea was to interview half a dozen people from the Lithuanian migrant community, allowing them to tell their personal stories and those of family members. I wanted to learn the details of how Lithuanian refugees settled in England at the end of World War II, including the following topics: how and why they had arrived in England; what sort of employment they found; what their living conditions were like; how they built homes and supported families; how the second generation integrated into English society; how the migrants managed to preserve their Lithuanian culture and identity; and what attempts they made to maintain or renew links with Lithuania and their relatives there.

I had already established a good network within the local Lithuanian community, and I was confident that I could find several willing subjects for interviews. Among my best Lithuanian friends in England was Audrone Ruliene, a fellow nurse who I had worked with for some years. She was supportive of my book project, helping me to brainstorm ideas and plan a course of action.

But my main inspiration was to be found closer to home, in Wolverhampton. Here I met Gene Ivanauskas, a warm-hearted lady who had arrived in England in 1947, along with her husband. They had worked hard and bought a house, and became founding members of the Wolverhampton branch of the Lithuanian Association in Great Britain. Gene‘s cultural contributions included the establishment of the traditional dance and choir group “Vienbye”, which put on many wonderful performances over the years, complete with some beautiful traditional costumes.

Gene said that she would gladly be interviewed for my book, providing me with the perspective of a first-generation migrant who could remember the hardships of the early years. She also put me in touch with a number of second-generation migrants – John, Terese and Gražina – who likewise agreed to be interviewed, along with another first-generation migrant, Kunigunda Gough.

I knew that the interview method I was embarking on was well established in the social sciences, and much used by local historians seeking a bottom-up perspective on the past. However, I didn‘t wish to be too formal or scientific in my approach. Rather, I sat down with each interviewee, switched on my recording device, and asked them to tell their migration stories, including whatever details they felt of interest.

The stories poured forth, captured on audio and video tape, and I only intervened to clarify a few details here and there. The interviews were recorded in English and Lithuanian, and I later typed them up in English, editing out any passages that deviated too far from the main topic of discussion.

My approach wasn‘t particularly scientific, but the results were exactly what I‘d been seeking: personal tales of migration, including a range of aspirations, challenges and triumphs. These personal tales formed the backbone of my book, providing a permanent record of human experience during a time of great historical change.

Years later, as I pondered improvements to the finished book, it occurred to me that there were a few gaps in the narratives. For example, while many first-generation migrants had clearly travelled to England from Germany, rather than return to Lithuania at the end of World War II, there was little said about why they made this decision. What was it that prevented their return to Lithuania in 1947, and how had they come to be living in Germany in the first place? History buffs may be able to answer such questions, but it seemed important to hear the facts directly from those involved.

And so, in early 2020, as part of the process of creating the revised edition of this book, I went back to my interviewees and asked a few of these outstanding questions. I also looked again at the interview transcripts and, with the help of David Stanford, teased out some important details that I had previously missed. I also started writing my own introductions to each person, inserting this new information wherever appropriate.

Community history

My core aim in writing this book was always to provide a platform for individual voices, to open a window on personal tales of resettlement. However, it soon became clear that these people had formed a vibrant community, complete with social and cultural events, and their own thriving community organizations. And so, I was more than happy to find that my interviewees recalled many details of the development of this community, bearing witness to the many live performances and celebrations that were organized, together with various religious and educational activities.

In the original edition of this book, I sought to tackle the topic of community development as a separate theme, relying heavily on material from the book by Kazimieras Barėnas. The aim was to give readers some idea of the activities of the Lithuanian Association in Great Britain, particularly within the West Midlands.