In a post-war world turned upside-down, the women face circumstances to test their spirit, resourcefulness & courage. Their future is unknown & the present uncertain, but their past forged bonds not easily broken.

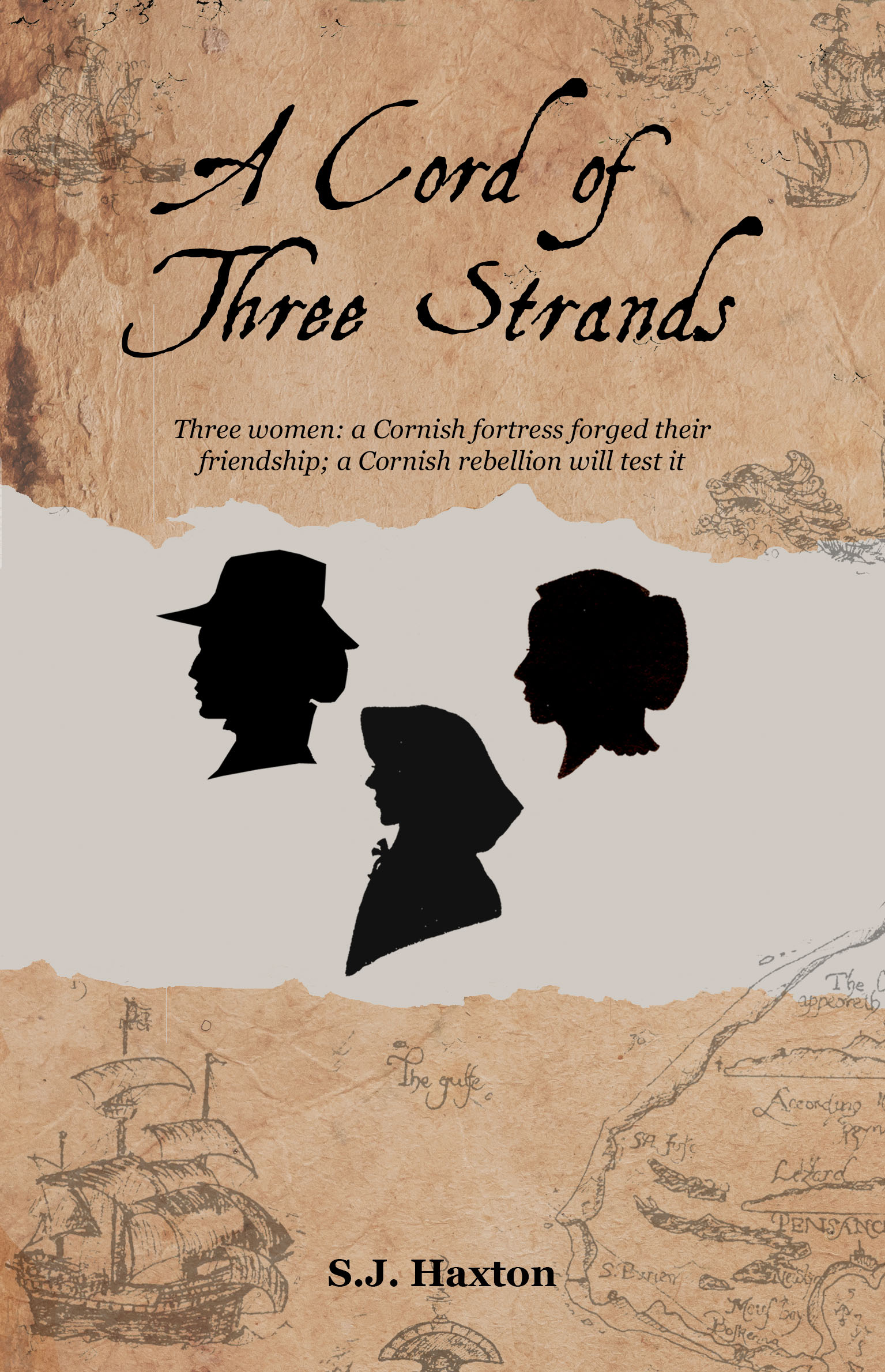

A CORD OF THREE STRANDS by S J Haxton

I Grace: A siege ends, peril begins

To my beloved son,

Do not judge as you read these words but believe they are the truth and will serve you well.

You were born in a beleaguered garrison, Pendennis castle, in the west of Cornwall, amongst the last company of King’s men and the pitiful following of their wives enduring the sultry summer of 1646, while elsewhere the nation bent to Parliament’s will.

At 2 o’clock on a thundery August afternoon, the sky overcast, air prickling with tension, nerves jangling in accord, we stepped out into a world newly made by generals and commissioners, where the King was a captive: a world upside-down.

I was too weak to carry you for long so Hester, who nurtured you when I could not, held you as, tattered, bareheaded, we straggled after the remnants of His Majesty’s army.

There was a travesty of a guard of honour. Hundreds of pairs of cold eyes marked our passage. Later we were to discover that, while one sympathetic gaze followed two unkempt women with a baby, there was another individual who, glimpsing a spectre from his past, made it his business that we would meet again.

The trumpets’ fanfares echoing off the granite walls and the steady thump of the drums moved our step. The limp flutter of the Royalist’s colours mirrored our mood. We made our way to Arwinch Downs to a provisional camp where we were documented, described, enumerated and scrutinized.

The first lie was the hardest.

A Parliamentarian officer at his papers was untidily scrawling, sweat glistening on his brow. Another stood beside him, looking less martial, quietly puffing on a pipe of tobacco. The clerk-soldier questioned first Hester then me, assuming that you were her infant.

He turned to me,

“Your man: what is his name?” Tremenheere Sark.

“His rank?” Captain.

“Which officer did he serve under?” Colonel Tremayne.

“What’s his state – walking or sick?” Dead.

‘Your man’ not ‘your husband’ he’d asked. So, with a lie and the stroke of a pen, I became Goodwife Sark.

Hester’s husband, William Mattock, had adored his feisty wife. Helped by the chaplain, the sick soldier wrote his last testament leaving Hester his share of the brew house in his village, Cornwood. Will died of the bloody flux two days before we learned of Pendennis’ imminent surrender.

Resolutely showing her papers to the official, Hester stated with a conviction born of innocence that there was income to maintain herself, the child and me, ironically now listed as her housemaid. As we were given travel permits and two shillings each, the bystander stepped forward. His voice was weary but kind,

“My name is Haslock, garrison surgeon, tasked with ensuring your welfare.” We probably looked wary; he continued, “That field kitchen will serve you light broth and bread, which should not compromise your weakened constitutions. Your onward travel is by sea, so I must judge how you fare tomorrow, to decide whether you embark.” Agitated, Hester exclaimed,

“By sea! Tomorrow? … But what are we to do tonight? Where do we sleep? The babe …”

“Accommodation is in hand, ladies. First, some food.” With a courteous nod, pointing with his pipe, he sent us to wait in turn for our first substantial food for weeks as he turned back to the table.

The aromas were almost too painful to bear. There were precious few possessions in Hester’s snapsack, but as the cook slopped out ladles of soup into her two wooden bowls, he gestured at a pile of torn loaves.

“One piece each!” he growled, “Take one for the bairn if you must …” Fortified by that tiny morsel of compassion, we moved into a roped area, joining rows of the vanquished. Some carefully picked at their food, others greedily stuffed their meal into their mouths. Hester and I savoured the broth slowly, nibbling at our bread.

Hours passed; wagons arrived. We bumped along lanes to a village, where we were packed into the upper room of the church house, a makeshift sleeping quarters. Told to rest, we were kept securely, the door locked. Churchwardens took turns to stand watch, ‘for our safety’, they said.

We slept only fitfully. As the moon rose, shouts echoing round the graveyard and a thumping downstairs that rattled the door-latch jolted everyone awake.

Bile rose as I recognised an accent, not quite Scots, and un-mellowed by time, still authoritative, still terrifying.

“Open up! I have business with one who I know is billeted here! Open up, in Parliament’s name!”

The man hammering at the door was not your father, but he was my husband.

II Hester: To make a voyage

Well, just when I, that was Hester Phipps and is now Hester Mattock, thought I would find myself on the up, here I am clinging on the rim of Fortune’s wheel and mired in muck just as deep as ever. Servant, thief, convict, wife, camp follower, widow; ‘tis how the wheel turns. Yet if a soul can get no lower, then surely the only way is for fortunes to rise.

Budock weren’t the first place Grace and I had shared a tiny bit of space but she, the babe, me and a score of other lasses lay head to toe and like pressed pilchards in an upper room of a church house while others lay in the room below, and it struck me that ‘tis summ’at funny how life twists and turns.

See, Grace and me had been together like this in a garret in Barnstaple back in ’45 even though Grace had once been my mistress back in Bristol. That seems a lifetime ago for all ‘twas only five years since. She told me how a sea captain, Fenwick, slyly courted her papa, only wedding Grace for her inheritance. Her father, God rest his soul, was hoodwinked and not all by honest deeds if a tattered book Grace showed me tells the truth.

She keeps it hidden close in what few belongings she carries, but it seems to me that book is a summ’at terrible burden if her husband decided he wanted it back, as well he might. It holds much that a man would never want cast abroad.

He’s a nasty piece of work is ship’s master, Bartholomew Fenwick. Grace used to cry out his name in her sleep and not in a good way neither and always I would soothe the nightmares, stroking her hair ‘til she stopped sobbing.

Anyways, night came and little Henry Charles - we do call him Hal - being suckled off to sleep, a tumult down the stairs stirred the dust off the doorframe. Grace sat bolt upright and grabbed my wrist but before she could say ought, we knew the name of the fellow outside a’cause he was a-banging and a-hollering, calling out his rank, his ship and demanding to be let in under pain of Parliament’s this and that.

Getting nowhere, then Fenwick’s tone turned, all silky like, saying there had been a terrible misunderstanding for his wife had been swept up in the day’s events and was now shut up in this place by mistake. He said he was come to take care of her.

Grace’s eyes were wide with fright, glinting in the moonlight. The other women muttered that he was moon-mad, but thankfully Fenwick must have smelled a bit fishy to the churchwarden. With some shuffling of his papers, next thing we heard was he crying back through the barred door that there was no woman of the name on the list.

“Medium height, slim, red-headed; she’s got an infant with her! My … daughter!” came the response.

Chills ran down my spine for he’d had half a chance of being right about the babe. Grace’s hand flew to the matted mess of her chestnut curls.

“Sir, all of these poor wights are but skin and bone, may God help them! And no, there’s no girl child here. There’s a baby boy but his mother is Widow Mattock and she’s swarthy, dark haired!”

I watched Grace as I clutched the grizzling Hal, soothing him as best I could. She prayed hard, hands white at the knuckles, her eyes tight shut,

“Dear Lord, let the warden not mention me, even by my new name, for the fiend will know…”

Now, I b’aint be a clever sort, yet I have sometimes had cause to ponder God and all His mysteries. I am sure He was listening to Grace that night, for next thing we heard was a right un-gentlemanly cursing. After a last two-fisted thump upon the door, the noise of footsteps on the stones outside gradually faded away, horses’ hooves clattering off into the distance until all was quiet again. Grace and me lay, eyes wide, the night long, no hope of sleeping, just holding hands for comfort.

Before the church chimes rang six, we heard voices approaching again. But ‘twas village wives bringing pots and bowls of a milky gruel. Some brought with them ragged garments, cast-off threadbare items, which they gave where most needed. For us there was a handful of old but serviceable napkins for Henry Charles, a cap that Grace passed to me and some worn linen as a serviceable head-wrap for her. I was tearful and asked why these strangers showed such kindness. A Cornish accent softly replied,

“My man, he was with Godolphin’s regiment. He came home to me. But I look at you and think there but for the Grace of God go I,” and, quieter still, added, “Long live the King!” Twenty voices murmured, ‘Amen’.

The churgeon arrived soon after, going among us women, speaking kindly, asking all manner of questions,

“Are you managing to drink? Sweetened water… good … but if you are offered food, eat but a very little at a time and slowly, slowly. How does your heart beat, regular and steady or fluttering, fast?” Some of us who were particularly feeble he set aside. The rest clambered onto the wagons and back we went to the encampment. As we jolted along, I mused,

“Grace, why is it you and I still stand when others ail so badly?”

“I cannot say” she sighed. “Perhaps we have a hardiness born of having to endure difficulties even before we came to this place?”

“Not God’s punishment, then?” I asked. Grace’s look darkened,

“What wrong did Mary Tremayne ever do that should draw down Heaven’s wrath?” Now and then, Grace could be snappish, but what she said was true. Mistress Tremayne is one of the kindest women I have ever met. She might have defied her family to marry the man she loved, and joined her husband at Pendennis when he bade her stay at home, but I thought God could not find fault in that, yet she fell sick at Pendennis, was now dead for all we knew.

The wagons took us back to a bustling camp, more than a bit afeard and dopey with lack of sleep. Still, I weren’t too mazed to know that amongst the militia was a danger. We were in full view of everyone, maybe even Grace’s husband. Soldiers were still checking on us and there’d be no hiding here. I had to get my papers out again, taking Hal to keep up the ruse we had begun the day before. We answered more questions. I hoped Grace could remember the fibs we had woven round the truth.

Eventually, my head aching fit to burst, they sent us to another queue, to await a wagon to take us to a ship to go by sea, to Yalme. But we were both thinking, which ship?

Hal was wriggly, peevish in the bright sunshine. I tried to keep his little head shaded but it was a struggle. A screaming child would mark us out, so Grace and I took turns to dandle him and walk about as far as we were allowed, which wasn’t far. Everywhere there was the stench of folk, unwashed. I suppose me and Grace didn’t smell too sweet either come to think on’t.

On one circuit of the ropes, I could overhear the orders for the little boats. Trying not to be obvious, bouncing the baby on my hip, I pretended to babble to him but all the whiles listening as best I could, then hurrying back to Grace.

“What did you say Fenw…” I whispered, not saying his name for fear of being overheard, “What is HIS ship called?”

“She was the ‘Ann of Bristol’ when she was my father’s. When Fenwick became a turn-coat they renamed her ‘Leopard,” she replied, heavily. It was the name we’d heard shouted the night before but, fuddle-headed, I’d not been able to remember.

“Then, Grace, I do believe we may be safe. I could hear them talking. Our vessel is the ‘Swiftsure’. The row-boats will fetch us within the half-hour!”

By evening we were aboard. When we asked to stay in the open air rather than take shelter, the sailors didn’t seem to care one way or t’other and Grace did not mind that I would not go below for it brought back bad memories of the first - and last - time I was at sea.

As darkness fell on our second night of freedom, for all I felt zaundy with the rocking and bouncing deck, I was happy, for surely we were on our way to a happy future, to a home on the skirts of Dartmoor, to Cornwood.

III Mary: Correspondence from Pendennis Castle

Written this 17th 18th day of August 1646

From my sickbed, Pendennis Castle.

Loving Papa,

The dutiful and loving wishes of your daughter come home with this letter to all at Penwarne. Parliament’s Surgeon Haslock, a compassionate man, has provided the tools for me to write to you but forgive my errors or that which that I forget to write for my mind and body are so weak, too weak to be allowed to stand, to come home. I can not come

Yesterday Lewis marched at the head of his men as this fortress surrendered yet returned today, diligent on castle business, required to sign and countersign endless papers, being one of the old Council of War. He is allowed to see me.

I think often of home, hope that you have forgiven me.

How are my sisters? Has Agnes finished the new coverlet for her bed? Tell her that to stitch and spend our hours in gentle talk would be my delight, to tell her of my adventure and of two women, who I now count amongst my dearest friends through the perils that we have shared these last months. I fear that their travails are not yet ended. Should ever they need succour I beg that Mistress Grace Fenwick and Mistress Hester Phipps would find it at Penwarne, for my sake.

It seems all our woes continue unless matters now come to a good conclusion for His Majesty.

The good surgeon tells me that the King is still with the Scots. Lewis says that he will might serve His Highness the Prince of Wales. He believes His Highness to be in Jersey but supposes he will soon go to Paris, to Her Majesty the Queen. Did I mention that the Parliament’s surgeon Haslock is tending me?

I lie in a cot in a chamber near to our old friend, Sir Henry Killigrew who has done much to keep tempers calm in these last days, for desperate men would have taken the great store of gunpowder to blow up the keep, planning charge out and die with as many of the enemy as they could take rather than surrender. Happily Sir Henry’s genial blustering and bravado became a distraction but he took injury from the discharge of his pistol inside the keep, an extravagance of powder but recklessly done, whereby a great splinter of wood gave him a wide gash upon his forehead yet I hear the patient loudly insisting that he will take ship for France.

And I must add to your loss with words that come hard.

Dear Papa, this morning Lewis came to show me our pass to leave this place, a small paper though it contains solemn matters.

I will tell you how our permit reads for only in such a way might I break my news more gently, though I can think of no way to be kinder.

“Suffer the bearer hereof Colonel Lewis Tremayne with his servants, arms, horses and goods quietly to pass unto St Ewe or any other place within the Parliament’s quarters or beyond the seas about their particular employments without any search, plunder or injury, they also being to have the benefit of the Articles upon the Surrender of the Castle of Pendennis.”

You see, Lewis has had to declare his intentions and I can no longer avoid that which I dread to write, for putting it in black upon the page makes it more immediate.

Lewis has chosen exile.

We will, I think, go to France, to the Prince of Wales. I am told there will be a ship provided.

I cannot now hope to be at Kestle Wartha where we wanted to make our home or even with you at Penwarne, but must go with Lewis. I can be nowhere else.

If God is willing, we will prevail through these perils and misfortunes. I truly pray that you understand.

I promise to write often, however many leagues there may be between us, and thus my correspondence will keep us close. Honour, loyalty, love - and hope - will inform my days wherever I may be and when you read of me, you will know that the cords that bind this family are unbreakable.

Your loving daughter,

Mary Tremayne

To John Carew,

The Manor of Penwarne

By Mevagissey in the county of Cornwall.