Chapter 1

Sartori figured that was his man Babcock leaning against the flat face of the Jeep FC 170 in the motel parking lot. Grabbing his duffle bag and aluminum attaché case, he headed out.

“Are you Babcock?”

“I’m your man. Bob, Bob Babcock.”

“Bob Bo-bab-cock. That’s a twister!” Sartori said apologetically. “I hear they call you Bobcat.”

“Yeah, you can call me Bobcat if you want; everybody else does.”

“Okay, Bobcat, I’m Frank Sartori.”

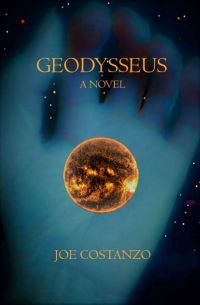

As they shook hands, Sartori eyed the stenciled word above the Corps’ red castle on the Jeep’s door and remarked, “GeOdyssey! Hey, that’s pretty clever.”

“Yeah, some smart-ass college kid in the paint shop did that,” Bobcat said with a snarl that must have contributed to the punning of his own name. “He acted like I was a knucklehead when I asked him what it meant. I know what geodesy means. I’m a surveyor, for Christ’s sake. But that’s not how it’s spelled. He had to explain it to me, and now I end up having to explain it to every other knucklehead who asks.”

Sartori laughed and then paused a moment to size up his man, noticing that Bobcat was doing likewise. He had been told that Bobcat was the best man for the job, not only an ace surveyor, but also battle tested in keeping his mouth shut. He was short – no more than a couple of inches above the recruit reject line – but built like a middleweight with a square jaw that looked like it could have taken one of Graziano’s uppercuts and asked for another, sir. He was wearing a Cardinals ball cap, crumpled G.I. utility fatigues and combat boots. He had a wary look that only partially masked a preference for fight over flight. At six-two, Sartori towered over him, and his rolled-up shirt sleeves and long, shaggy gray hair and beard gave away his civilian status and waning middle age.

“Thanks for volunteering for this job,” Sartori said. “We could be gone quite a while.”

“Well, Frank, I’m always being volunteered for jobs no one else wants,” Bobcat replied, drawing a pack of Camels out of his shirt pocket and offering him one. “But I’ve got this spanking new office on wheels, a load of the best equipment my rich Uncle Sam can buy, and I’m taking orders from some guy I won’t have to salute or call sir, so I guess you could say this one might be more to my liking.”

Declining the smoke, Sartori said, “Fine, Bobcat, but listen, I’m here to give you directions, not orders. If I get it wrong, you set me straight.”

After stuffing his duffle through the slit in the canvas shell over the bed, he climbed into the cab and set his attaché case on his lap. The Jeep’s engine rumbled under their seats and Bobcat steered them to a stop at the roadway.

“You can start by giving me those directions. Which way?”

“We’re going all the way up the 93 and then a few miles more on a dirt road north of Route 66. It’s about one hundred and seventy-five miles altogether, and then we’ll make our own road west from there for a couple of miles. I have the coordinates,” Sartori said.

“So, what do you need me for?”

“I can read a map, but I’m not a surveyor. I could miss it by a mile.”

Sartori could tell that Bobcat wanted to follow up with the question that was probably uppermost on his mind – Miss what? – but he knew, or more likely had been ordered, not to ask. Flicking his cigarette out the window, Bobcat, to his surprise, asked it anyway.

“Miss what?”

Actually, he didn’t mind the curiosity, the legitimate inquisitiveness, as it demonstrated he’d be working with a bombardier of a man who wasn’t about to target a drop without knowing what the hell they were blowing up. Anyway, he had a plausible answer to that question. He had tried out versions of it – mostly successfully – on his own chief, Bobcat’s superior officers, the Air Force aeronautical science liaison, and the CIA case coordinator. Mostly, because the CIA’s man, a former OSS flatfoot who possessed a deep, wide, and detailed knowledge of Germany’s kaput and Russia’s nascent aeronautical capabilities, had seemed skeptical of the foreign intrigue scenarios that Sartori had proffered. The CIA’s CC suspected the United States Air Force itself was responsible, even though they denied it at the highest level. He said his agency could get to the bottom of it without chasing down the flock of wild geese Sartori was after.

Jabbing at Nellis, Edwards, Luke and Sandia on the map with a lethal letter opener, he had noted, “Look, they’re all four within spitting distance of that damn thing. Congress has given the Air Force so many new toys to play with, it’s Christmas every day. Trust me, it came out of one of those bases, and that’s where we should be looking.”

“I don’t know, maybe nothing,” Sartori said to Bobcat. “The coordinates – four sets altogether – were found a few months ago inside the wreckage of some kind of cargo pod or capsule that apparently fell or was jettisoned out of an aircraft over Death Valley. The old rock hound who stumbled across it said that from a distance it looked like a tent out in the sage brush so he drove out to see who was crazy enough to be camping out there. It was domed, but it was a lot taller than a tent, and it had robust framing and a metallic exterior. At first, he thought it might be a storage container that someone had dumped, or maybe an abandoned hut. But it sat in what looked like an impact crater. It was tilted, and the side that had sunk deeper into the ground was slightly crumpled. So, he assumed – correctly, we think – that it was dropped from an airplane. He judged from the size of the mesquite that had crawled out from under it that it had been there thirty years or more. That would have put it there sometime in the 1920s. No one believes that, of course, because the airplanes back then wouldn’t have been carrying anything like that. It’s more likely that it came down recently and just landed on top of a thirty- or forty-year-old mesquite.

“The rock hound chained it to his pick-up and dragged it all the way to the junction. He intended to sell it for its scrap value, but there were no salvage yards within fifty miles. So, he started asking around if anyone wanted to buy it for a storage shed or a chicken coop. When he couldn’t find a buyer willing to pay the fifty dollars he was asking, he dragged it to the gate at the Proving Grounds. One of my colleagues at the AEC saw it and thought it might have been a military drop, so he persuaded the base to spring for the fifty dollars.”

“Well, what was it?”

“Like I said, a dome shaped capsule, probably a cargo pod. We’re not sure what it was used for, where it came from, or how it got there.”

A dome with four stubby triangular legs set over a square base; a pendentive dome, more precisely, shaped like the one atop Hagia Sophia, the shrine to Logos, at Constantinople. It was large enough to have held the cab they were sitting in with head room to spare. The four pendentives splayed out below the square bottom of the pod like table legs. One of these, the first to hit the ground, was bent, and it was that corner of the pod that had sustained some damage, though it was not ruptured by the impact. Curiously, instead of the expected sharp vertices at the tips of the pendentives there were only flat circular surfaces with shallow tapped holes, hinting at extensions that had been removed before it fell or that had been dislodged during the fall. The capsule was made out of some kind of a lightweight, predominantly sodium-gold alloy that had thus far stumped the metallurgists and that might have made the rock hound a very rich man. A missing hatch gave the investigators access to the interior of the capsule and suggested that whatever, or whoever, it had held had been ejected before it crashed. But he was operating under a strict need to know basis, and Bobcat didn’t need to know any of that.

“We’re checking it out,” he added, “because if it wasn’t one of ours, then it must have been one of theirs.”

It was with that insinuation – that the Russians might be involved – that Sartori had prevailed over the CIA and won the assignment and the expensive resources, including Bobcat and the Jeep full of equipment. As someone tasked with assessing any possible poaching of the Atomic Energy Commission’s nuclear secrets, Sartori had parried the CC’s jabs at the map with a thrust at the Nevada Test Site, a stone’s throw from Death Valley. What if it was the Russians dropping in for a look at what kind of nukes the U.S. had up its sleeves? Those commies were capable of anything. Sartori knew better, but he was not above fishing with red bait.

“Okay, so you don’t know much,” Bobcat surmised, “but they found aeronautical charts in the thing?”

“Not exactly. They found a metal disk with four little dots arranged in a symmetrical pattern on a grid. Next to each dot was a series of geometrical shapes that appeared to be a graphic code,” he explained. “Our codebreakers in Washington said that during the war they sometimes came across symbols being used to represent letters or numbers. Those on the disk looked to them like numbers because there were nine recurring lengths used on the sides of the geometric shapes. When they teased out patterns, the numbers began to look like coordinates. But they admit it’s just a theory.”

All of that was true. The disk, about the size of a silver dollar, came out of a slot in the wall close to the hatch. The walls themselves looked as if they had been scoured clean and powdered dry with a white dust, like the ash inside of a blast furnace. The grid, dots and microscopic coding on the disk appeared to have been etched into its surface by an impossibly precise thermal process that had also thus far stumped the metallurgists. The marks definitely hadn’t been stamped, cast or machined. Attempts to shave off a tiny flake or grind off particles of the disk for analysis had failed. It was impervious to the usual sampling tools, and the metallurgists were seeking authorization to employ more drastic techniques that admittedly might damage or even destroy the disk, which angered him every time he thought about it.

Bobcat looked as if he were about to ask the next question that had sprung from the last one, but he lit another cigarette and turned on the radio.

“You wouldn’t believe what I had to go through to get this Motorola installed in this thing,” he said as he dialed through crackling and whistling static in search of a station. “They ran it up the chain of command like I was requisitioning an M48 Patton tank, for God’s sake.”

He overshot a signal and dialed it back just as “A White Sport Coat” and the pink carnation was wrapping up.

“Glendale’s FAY-VOR-ITE son, Marty Robbins!” howled the DJ. “K-R-U-X A M’s 50,000 watts frying your brain! Hey, truants, these are ‘School Days.’”

Bobcat turned the volume down and continued, “I told them, if I’m going to be on the road for who knew how long – they didn’t – then I wanted a radio just in case you turned out to be a stiff. No offense.”

Taking none, Sartori asked, “Weren’t you always on the road? I heard they pulled you out of Alaska. The roads up there are longer than anything we’ll be covering.”

“Yeah, when there were any roads, but up there I was with thirty-man field parties. We worked hard to make sure we had all the charts we’d need to stop the Russians in their tracks if they ever tried to cross the Strait. But, you know, at the end of the day and in between camps, it was not so bad. You don’t need a radio to pass the time when a pal’s telling you about how he once got away from a bear that chased him up a tree. You heard a million stories and you couldn’t always tell if they were bullshit, but they were like songs without the music, if you know what I mean. Anyway, there were no radio stations up there, so it’s not like I had a choice.”

“How did he get away?” Sartori asked.

“The guy in the tree? He spotted a beehive in the branch above him. After pondering the risks, he figured bee stings wouldn’t be as bad as a mauling. So, he grabbed the hive and threw it in the bear’s face, you know, like Moe hitting Curly with a pie. He said the bear actually seemed grateful, or distracted, anyway, and the guy jumped down out of the tree and ran like hell. After a taste of the honey, the bear lost interest in him, but the bees chased him all the way to the river. He said he got stung in the face so much that his eyes swelled shut, and some of the bees somehow even got to his tongue and up inside his nostrils. He couldn’t see or eat anything but cold salmon broth for more than a week. Someone else had to spoon it into his mouth because his hands burned like they were on fire. He said if he had it to do over again, he’d take the mauling.”

Sartori laughed along with Bobcat, saying, “A Cornelian dilemma!”

And then realizing that he had morphed into the smart-ass college kid in Bobcat’s rolling eyes, he quickly added, “One choice was as bad as the other, wasn’t it?”

“Yeah, obviously,” Bobcat replied, turning Sartori into the knucklehead. Looking over at him as if to make sure, he said, “You’re Italian, huh?”

“Half, on my father’s side,” Sartori said.

“I was stationed in Italy after the war with a unit that was rebuilding bridges,” Bobcat said. “I was having a good time until they sent me to Monte Cassino to triangulate and map land mines that the Germans had left behind as a little going away present. Worst job I ever had. If you ever want to feel what it’s like to be one step away from a bottomless black hole in the ground, take a walk through a mine field.”

Sartori was taken aback by the description, which accorded with his own perception of death.

“I’ve never been to Italy,” he said. “But I think my father was born there.”

“Think? You don’t know?”

“I never knew my parents. I was raised by an uncle on my mother’s side. He was a professor of physics at Princeton. This attaché case belonged to him,” he added, tapping the aluminum lid.

“A professor. That figures. My dad ran a hardware store in St. Louis,” Bobcat said. “I learned a few things from him, too. He taught me how to make a compass by setting a two-penny nail on an anvil pointing north. You hammer it flat enough so that you can drill a little hole in the middle of it. Then you hammer it some more until it’s as flat and thin as the back side of a bobby pin. Then you set the hole on the tip of a thumb tack and let it spin. There you have it. Points north. Now, I’ve got some of the most expensive compasses in the world bouncing around in the back of this Jeep and they do pretty much the same thing as that two-penny nail.”

“It takes more than a compass to do what you do,” Sartori observed.

Bobcat shrugged off the compliment and turned up the volume on the radio to catch some more tunes before they’d be out of range of KRUX’s 50,000 watts. Sartori calculated they’d lose the signal about halfway to their destination, enough time to listen to half the Top 40 or share a few more of what Bobcat had called songs without the music. Sartori preferred the latter. He was enjoying Bobcat’s take on things large and small, from bears in trees to the strategic importance of the Bering Strait, and from a child’s magnetized nail to a soldier surviving at the brink of a bottomless black hole.

He hadn’t always taken pleasure in small talk and tall tales. His uncle, a brilliant, taciturn physicist named Pieter Kierkig, had instilled in him an understanding that the single-minded acquisition of knowledge and dispassionate awareness of the world around him was the only reason he was put on this Earth. It was not until he was immersed in his graduate studies at Princeton and beginning to feel confined and excluded from that very world that he finally asked himself and, eventually, his uncle, “But, to what end?”

“We are an experiment,” his uncle had replied, offering no further explanation.

Yet, he would gradually come to understand and accept that answer because it suited him. Like any good experiment, there was something to be learned from one’s existence regardless of the results.

Comments

Great start!

Promises to be a fun adventure.

Great start

In reply to Great start! by Jennifer Rarden

Thank you, Jennifer. Writing it was a fun adventure for me, and I hope readers will share in it.