An audience member stands. “What is the meaning of life?” he asks.

Stephen Levine, author, poet best known for his work on death and dying, sits on the large stage looking down at a hundred expectant faces. I am at the Open Center in New York City at a two-day seminar.

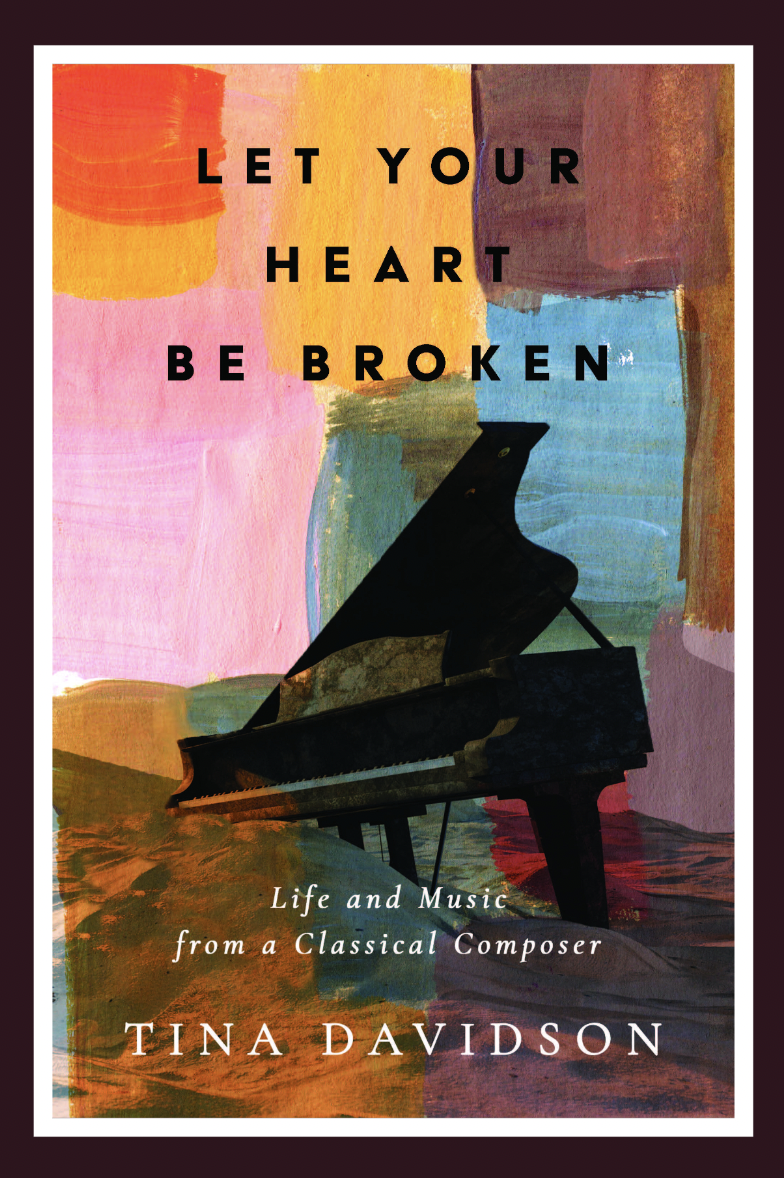

He relaxes back into his chair. “I am asked that all the time,” he replies, his voice burnishing the microphone, “and I really don’t know.” He pauses, looking to the side. He turns back, smiling. “But I think the meaning of life is to let your heart be broken.”

The heart, the round sphere of your being. Let your heart be broken. Allow, expect, look forward to. The life that you have so carefully protected and cared for. Broken, cracked, rent in two. Heartbreakingly, your heart breaks, and in the two halves, rocking on the table, is revealed rich earth. Moist, dark soil, ready for new life to begin.

O V E R T U R E

M E M O R Y ’ S P A S S A G E

The way back into memory is circuitous. The path crisscrosses, dead ends, starts up again, and changes directions. Darkness opens up to light, colors kaleidoscope, and shapes are broken into a thousand patterns.

The past presses on the present with staggering consistency. Nothing is separate or fresh; always an afterimage. The slow time-lapse photograph catches the multi-image movement of our lives. Danger lurks in every corner. To reconstruct will challenge perceptions of self, to restore will allow old pain to well up.

The price of forgotten memories, however, is more costly. My puppeteer of darkness is cruel. He perpetuates false beliefs and forces reenactments I cannot control.

The miracle is light. The miracle is that we rise again out of suffering. The miracle is the persistence of the soul to find itself, to look hard into the darkness, reach back, and grasp remnants of ourselves. The miracle is that we create ourselves anew.

As I look back at all of this now, my daughter was my great opportunity. Born on a cold Thanksgiving Wednesday in 1984, Cassie was a beautiful compact shape, and came without complications. I spent the holiday in the Philadelphia hospital grateful and humble.

Wood and I were delighted new parents; earnest, starry-eyed, arrogant and foolish. Together we measured every change, smiling indulgently at each other. I nursed with great abundance; Cassie preferred one side, and I grew happily unbalanced. I was writing music that felt rich and authentic, pleasing me for the first time that I could remember. A cello concerto for the Sage City Symphony was my first paid commission, and the melodies soared, the rhythms snapped. The garden was full of flowers, the sun was hot. In the early mornings, I lay in my airy bedroom filled with soft blue light, snuggled next to this little form, breath to breath.

In truth, my life was falling apart. My close friendships were angry and blistering. My relationship with my sister Eva, who, with her husband, had come down to live in the upstairs apartment, erupted. In the midst of the joy, my life was teetering, and I couldn’t understand why. The structure I had built creaked and swayed. I woke at night in a rage, and fought battles with phantoms. I obsessively sorted through arguments, wrote long letters, destroyed them, only to write them again.

The only quiet I had was when I nursed my daughter. Her plump hand reached up, stroked my neck, and twirled my hair. We were peacefully one.

I could descend into forgetfulness and depression as I had done so many times in the past, or I could put my hands and heart to work. Her small life hung in the balance.

I sat in the therapist’s basement office. She tapped a pencil against her notebook, thinking. This is ridiculous, I told myself, promising to stop therapy at the end of the session. The afternoon was beginning to darken, and the rows of casement windows were full of shadows.

“Tell me that dream,” she encouraged me again, “as if you were dreaming it now.” With a sigh I allowed my eyes to close and relax. I had only twenty minutes left to the session. I could manage this last task.

My nights had always been haunted by dreams of damaged houses and silent, empty rooms, of basements moist with dark lagoons, of sleek black dogs tugging at my pant leg, and of dangerous men lurking in alleys. But the most vivid, persistent dream, one I had since I was three years old, was of an elevator. Once the doors closed, it tipped precariously to the side, stopping between floors, opening finally to a dark hallway. The silence was leaden. Closed apartment doors stretched off out of sight. I woke gasping and sickened.

“Why don’t you get off and walk down the hallway?” my therapist suggested.

I step out tentatively. The hall curves. The carpet is old and scuffed, the walls are grey. I slide my hand on the cool plaster as I walk past closed door after closed door. Suddenly a door is open; the room is filled with light.

“Go on in,” she reassured me.

A little girl is looking out the large glass window. She is small, her dark hair sweeps up on her soft pink cheek. Her profile is etched against the horizon. Her palm is on the window, her breath makes soft moist circles on the glass. She waits and watches.

“Who is she?” Her voice was warm.

If she doesn’t move, if she just stays right here, Solvig will return. I will not move, I will be good, and oh so still; and Solvig, my Solvig will find me.

My eyes opened suddenly. What was unearthed here? What was forgotten and split off from me? I recognized myself, but my mind did not comprehend. The facts were well known; I lived in Sweden for three years with a foster family, Solvig and Torsten. My mother returned and I left, she told me, without once looking back. My mind rushed up and swirled.

Lonely and solemn, little Tina has not moved from her place. “If you get lost,” she was surely told, “stay where you are – we will find you.” Patient and quiet, she waits for Solvig. She waits for me. Guardian of secrets and memories; my shadow – the real image the body creates in front or behind oneself.

Here was the heart of loss. To my three-year old self, my foster family was my family. The day my mother rang Solvig’s doorbell and brought me home as an adopted child, I lost my first mother and father, my three brothers, a home, a country and a language. I lost myself and became another child. The shining child stayed behind, waiting at the window. The dark child emerged. To the passing eye, I was unremarkable, even normal – but my inner self was silent, dark, and eternally sad for a loss that had no name.

That day in the therapist’s office was the first in a decade of self-discovery. With her loving help, I pieced my childhood and myself back together. I collected fleeting images, dreams, and snatches of conversations and created my own crazy quilt of my early life with remnants, embroidery, and bits of ribbon.

The path of memory was littered with startling beliefs and perceptions that operated, silent and deadly, behind the scenes. My progress was uneven. I reworked an understanding, leaped ahead, then wallowed for weeks in a fog. After a remission, I emerged to work on a new piece of the puzzle. The darkness began to lighten, my rage abated, my depressions lessened; I began to breathe.

C H A P T E R 1

G R I E F ’ S G R A C E

Solvig holds my arm as we turn to the camera. It is 1954, and we sit on a wooden bench, our feet tucked in the sand of the beach at Malmö. My two-year old face is thrown back, my short black hair swept by the wind. I am relaxed in a smile.

The photo is a surprise. Thirty years later I study it carefully for the first time. A finger print smudges the edge. Solvig is movie-star slender, and stylish in her sunglasses and short curly blond hair. We are dressed in white blouses and colorful skirts. She has me firmly at the elbow; her grasp is loving and protective. She keeps this child from flight.

I was on the phone with an international operator. [HS8] I was suddenly possessed in 1986 to find my foster family, the Elmståhls, with whom I lived in Sweden . I had been nestled deep there, adored as the only girl with three older brothers, Sven-Johan, Ulf, and my almost twin, Kjell-Olof. But I have not seen them or heard from them in over thirty years.

I braced myself in the corner of the kitchen and looked out into the side yard. February left the earth hard and bare in Philadelphia. The old crab tree’s large trunk was wet with snow.

My mother had no idea how to find my foster mother. “Solvig and I stopped writing each other years ago,” she exclaimed, exasperated. “Why don’t you call the international operator and ask for her phone number?”

It was like a bolt of lightning. I trembled. For days I hesitated, pulling my courage together.

The operator was kind. “Sorry, there are no Elmståhls in the Malmö area.” A keyboard clicked faintly. “I can check in the southern region of Sweden,” she added helpfully. “Yes, there is a Sölve Elmståhl in Lund. Perhaps he will give you information.”

I dialed his number and waited for the phone to switch over to an international call. The tone changed to the old-fashioned ring. A man answered. It was that simple.

“Hello, this is Tina. Tina Davidson from the US. “I used to live with your family,” I breathlessly guessed.

“Of course.” His warm voice poured out of the phone. “They always told so many stories about you.”

He was Sölve, the fourth son, born less than a year after I left[HS9] . Solvig had been so distressed at my departure that she decided to have another child immediately. He filled me in on the rest of the family.

“And Solvig?”

“She died of pulmonary carcinoma less than a year ago.”

My legs buckled; I slid down the cabinets to the floor. She smoked heavily, became ill, and stopped talking. Eleven months ago.

I sat on the floor for a long time after the call was finished, tears soaking my face. I hadn’t realized the depth of my desire to hear her voice, feel the touch of her hands. But she had not wait for me.

Thirty years without her, and this narrow miss. This ever-so-slight beyond my grasp was eons of time. No sooner was my journey to find her begun than the door closed. She, my first mother, was lost again, irrevocably. What remained was grief.

Grief waited for me, patient and enduring, lurking behind my eyelids, coloring my life grey. The grief I did not know, hidden underneath the bed, stuffed in the back of the closet, locked behind closed doors, now emerged. I began to remember.

Like a hundred years of rain, grief poured, thrashed, and flooded; cascaded, thundered, then drizzled for months. Finally, there was a calm day between downpours. Still steamy and moist, the sky was colorless behind the clouds. My lungs filled with air for a moment.

Then more rain, washing in like a sudden storm; my body ached. Soon, however, another lull, a break in the weather. The sun is pale at the horizon.

Grief’s grace, like a dewy mist, is the soft smell of spring returned.

C H A P T E R 2

M O R N I N G S

P H I L A D E L P H I A (1 9 8 6 – 1 9 8 7)

“One must aspire to be a slave to sound.”

Lionel Nowak[i]

March 1

The day is spent absorbed in composing. I sit here in my studio and look out the tall window on the old magnolia tree, whose double trunks twist around each other. The bark is grey and smooth. Flowers bob in the breeze. The dog’s nails tap on the floor. She settles down with a long sigh.

My work has taken on a personality I didn’t expect. The music moves from dissonance and distance through hypnotic ripping of chords and becomes more tonal, until finally the melodies come sweet and strong. I am uneasy about the transition, but let it be.

This month has been calm and certain, but as the composing winds down I become sad. At night I lie in bed next to Wood, wide-eyed under the skylight. Our daughter Cassie’s breathing is audible from her bedroom. I had a haunting dream last night.

March 12

The end of the piece is in my ears. The ascending patterns reach above themselves, blindly searching with closed eyes and bare fingers. A complete calmness. The beginning empties up into the light, with more and more emotion.

But, I feel so much anger. I want to write this Clear Piece, but I cannot. My rage, the wrenching away, the intensity of not understanding my life keeps me from moving forward.

Am I a fragmented person, incapable of putting together a long, unified piece of music? If I open myself up to the joy and love that is there behind all those tears, will I be able to do more than one large ensemble scream?

My music becomes more and more tonal. I pause. My dissonance has protected me. Will I take such a risk and move into a tonal direction?

March 15

Yesterday we went with a friend to the Arboretum. The grey woods were beautiful against a grey sky, these slender distinctions. As we walked, I spoke about Sweden. Cassie picked up stones, holding them close to her chest in her chubby eighteen-month-old fingers. A small human magpie.

April 1

The shape of the piece becomes clear. There are options for open orchestration with an improvised section moving into rhythms, and finally a return to the chords (a bitterness creeps back in) – its insistence is loud – a flash and then a calming down. A Swedish melody emerges like ray of light. It is slowly reabsorbed into the fabric of the soft, undulating chords.

April 3

What kind of sense does this all make? Why is it clear? What is the flash? A return to chords?

April 15

Night sweats. I am back in my childhood years in Istanbul. An idea for a new piece emerges; back to that room up beyond the stairs (those terrible secrets).

April 25

Requiem for Something Lost came out like a tubercular blood clot for saxophone quartet and pre-recorded tape of rustling whispers. As I wrote, I worried it was too strong, too revealing.