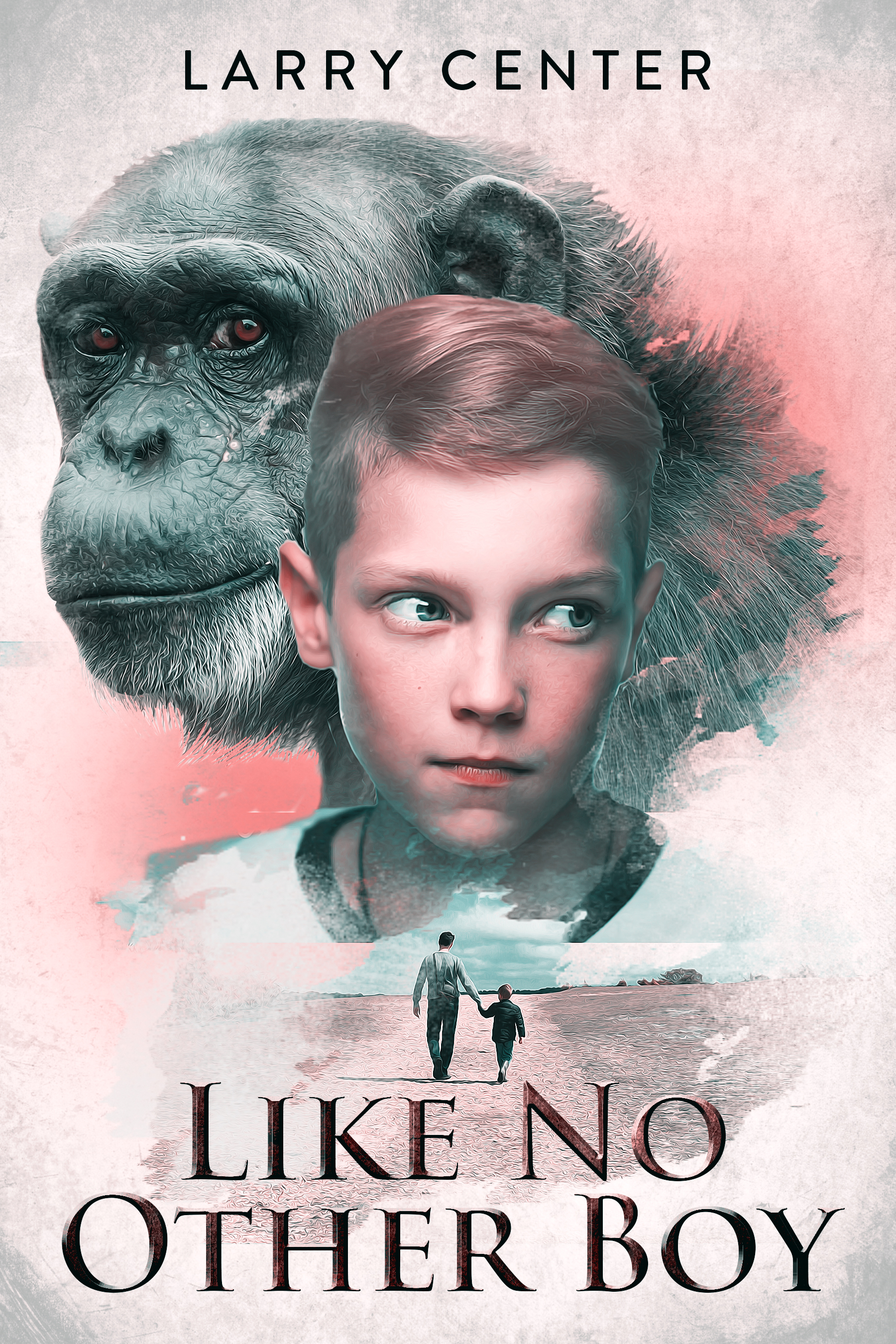

LIKE NO OTHER BOY

A Novel

By Larry Eisenman Center

“Oh! What things unspoken trembled in the air.”

—Johnny Mercer, A Handful of Stars.

Chapter 1

“The Voice in my silence.” –Helen Keller

It was a Saturday afternoon at the San Diego Zoo, a beautiful day with a pale blue sky. Tommy and I were standing in front of the zebra exhibit. The zebras were running around and nipping at each other, kicking up dust, tails swishing. But instead of watching the zebras, Tommy stepped away from the enclosure and looked down at the ground. He made his usual droning noise that sounded like a motorboat engine, then put a hand to his mouth and gnawed on his knuckles. They were already reddened to the point of almost bleeding.

He was eight years old and still biting himself. I watched him and winced. As his father, no matter how much I’d seen him do this, it still hurt to see my little boy harm himself.

In the distance, a lion roared as if he were trying to remind himself of his own kingliness.

“Wow! Look at those zebras, Tom-Tom,” I said, hoping to squeeze at least a drop of interest out of him. I was always trying to make Tommy pay attention to something in the real world, anything, desperate to get him to look and respond. “See their stripes? Aren’t they cool?” I gently pulled his reddened hands away from his mouth. “Zebras like stripes. Strange, huh? If they see stripes painted on a wall, they’ll stand next to the wall. Is that crazy or what?” I’d just read that on a sign nearby. It was an abstract idea to present to him, I knew, but I did it anyway.

Smells of espresso, popcorn, and grilled hot dogs filled the air while crowds of people swarmed around us. Tommy chewed on his hands again, the backs turning wet with saliva that glistened in the bright afternoon sun. He’d been biting himself, self-abusing like that for nearly three years and nothing we’d tried, none of the therapies, seemed to be able to make him stop. Frustrating wasn’t the word.

“Wouldn’t it be cool to ride a zebra? I sure think so,” I said, still trying to draw Tommy out of himself.

I stepped closer to him and knelt down to his level, bringing my face close to his, but Tommy’s foggy stare continued to wander off into the distance. He shrugged and said nothing. This was no-speak, his own secret code. He turned completely away from me and hummed louder. “Ouuuu . . . drrrrrr . . .” Sweat stains dampened the back of his blue shirt. Seeing how disinterested he was made my stomach feel like it was filled with gravel. I rose back to my full height.

Though his mind was an odd black box, Tommy’s face was close to angelic: symmetrically aligned features on pale, porcelain skin, curly, honey-wheat hair; and long lashes that shadowed eyes so big and blue there was little room for the whites. A gorgeous kid, for sure, a potential child model, tall and gangly for his age. He walked on his tiptoes with a kind of pelican strut, head before body, neck outstretched, legs following.

As I watched four young boys gawk and giggle at the zebras, Tommy spun around, arms extended like a propeller, eyes closed. He looked like he was trying to make himself dizzy. The whirring sound he made turned into “beeeeep, beeeeep.” Then he stopped spinning and slapped himself on the forehead. Just like that. Thwack. I felt a resonant pain in the deepest regions of my gut that seemed to spread through my entire body; empathy pain. I felt it all the time.

What I wouldn’t give to heal this son of mine, to turn his life around and give him the gift of a normal childhood, or at least something much closer to it.

“Please don’t slap yourself,” I said. “You know that’s not right. Come on now, let’s have fun here. Zoos are fun.”

But Tommy just looked away, still staring into space. He kept to his own planet, my far-away little boy. I felt like his distant moon.

This was our first trip to the zoo and I was on tentative ground. I’d been looking forward to our time together all week, since seeing the ad on TV that had grabbed me: lions, tigers, polar bears, plus some dandy pandas as well—oh, my! Tommy was mine on weekends, thanks to the shared custody agreement after my divorce. Usually, on Saturday afternoons, we went to the park near my house or worked on puzzles indoors, or just kicked back and watched TV. For us, this was quite the unusual outing.

We left the zebras and their antics and shuffled along the winding sidewalk that flowed around the exhibits. I showed Tommy the giraffes, a nosy lamb at the petting zoo, and two enormous elephants that flapped their ears and lumbered lazily around. He hardly seemed to notice them.

Even a unicycling juggler throwing yellow balls into the air didn’t stop Tommy from going after his hands again, chomping away at his nails and skin. Wearing a polka-dotted shirt and a great big smile, the juggler stopped in front of us. He tossed balls up and down in revolving circular patterns, catching a ball or two behind his back. It was a show, a real eye-catcher.

“Wow! Look at that juggler, Tom-Tom,” I said, pointing. “Isn’t he good?”

But Tommy was more interested in a nearby pile of dirt. Moving away from me and withdrawing even deeper into himself, he picked up clods of it, squeezed, and then let them fall. Now his hands, already wet, were a mess. Great.

As I reached for a wipe from my backpack—wherever Tommy and I went, Mister Backpack went, too—I noticed a father and son sitting on a bench not far from us. The boy, dark-haired and pudgy, appeared to be around Tommy’s age.

“Daddy, a juggler!” the boy said, excited. “Look!”

“He’s good, isn’t he?” The father fiddled with his phone as he spoke.

“Maybe I could learn to juggle like that. He’s so cool! Hey, Dad, can we go see the reptiles next? Please? We learned about them in Miss Wexler’s class.”

“Sure, son.”

Jealousy stabbed me. While that kid was having a normal talk with his dad, Tommy was picking up a rock and putting it down, picking it up and putting it down, then crumbling a leaf in his hands. He said not a word. This was his way, hyper-focusing on a particular object and blocking out everything else around him.

The juggler moved on. I kicked at the ground, Tommy-like, and swallowed hard. “Okay, Tom-Tom, let’s go check out some more animals,” I said, trying to maintain my encouraging tone.

“Daddy.” Tommy shook his head, looking past me. It had been his first word in a half-hour. “Go. We go.” He spoke in what I called brick-words, words that all sounded the same, as if they dropped heavily from his mouth pre-formed, one on top of the other in monotonic units.

“Really? But we haven’t even seen the reptiles.” I faced him. “Don’t you want to see the reptiles? The snakes and stuff?”

“Go. Go. Pleeeeease. Go.” Tommy hung his head and fidgeted. He put his right thumb into his mouth, then whirled around. I always saw his persistent hand biting, his spinning, and his motorboat buzzing as sounds that reflected the storms deep within his mind.

“Sure. Of course, we can go.” I gave him a smile. I wasn’t about to push him past his limit.

Tommy seemed unfazed by the big things in life, like being shared between his parents, living in two houses, and getting emotionally tugged this way and that ever since Cheryl and I had divorced two years ago—my uncivil war as I called it. Yes, he had his fixed routines, but he’d seemed to take the change in his parents’ relationship in stride. It was the impact of unexpected sensory experiences—crunchy peanut butter, the label on the back of his shirt, even the sight of the Sunday newspaper in disarray on the floor—that made him whine and pitch fits. These roadblocks could bring the neuron highway of his mysterious mind to a painful standstill.

When Tommy found a cigarette on the ground and reached for it, about to pick it up, I pulled his hand away just in time.

“Don't, Tommy. No! You know better than that.” He would have put it in his mouth if I hadn’t stopped him. I took a long breath and released it slowly, my eyes landing on a red-haired child eating pink cotton candy, swirls of it like edible clouds. “Okay. Let’s go, then. I guess we’ve seen enough.”

“Go . . . Go,” he said. His words seemed so disconnected, as if they arose not from his wants and needs and emotions, but from some kind of word-producing system inside his body that spat out vowels and consonants.

But on the way to the exit, we wound up near an African bird exhibit in a less populated area of the zoo. With Tommy still humming and murmuring by my side, oblivious to the world around him, I followed a long and winding trail. Instead of taking us to the exit, the shade-covered path ended in Primate World, which was set back on its own. Sounds of chimpanzees shrieking in the distance made Tommy stop dead in his tracks. He blinked, then moved forward with caution. He stood higher on his tiptoes and made a soft, inquisitive sound. “Oooouuuuwoooo.”

“What’s wrong, Tom-Tom?” I asked, narrowing my eyes. I knelt down to his level. “Are you all right?”

Tommy just sucked in a big breath as if he were about to blow out a birthday candle, then shuffled on as I followed behind. Instead of complaining, he headed straight for the exhibit and entered. He seemed suddenly curious. Interested. And I was intrigued.

From a distance of about fifty feet, we could see a single large and hairy chimp, chomping on leaves in the sunlight, separated from us by a thick glass panel. Tommy’s face flushed.

“Hairy so much,” he said, pointing at the chimp. “Wow.”

“Yes. They’re cool, for sure. They’re chimpanzees. You like them?” I rubbed my chin as I studied him, then glanced at the chimps.

“Wooooow.” Tommy clapped his hands. “Woooweeeee. Go. Here.”

“Sure.” His newborn enthusiasm made me smile broadly. It was just so completely unexpected.

As we made our way down a narrow path shaded by large overhanging trees, we found a group of chimps set behind glass walls, nestled in a jungle-like atmosphere. Large climbing rocks and verdant trees abounded in a field of grass and bushes. It looked homey, like an outdoor chimp hotel. Some of the chimps were playing or cuddling, some lumbered around, and others simply sat by themselves and stared vacuously into space. Tommy pointed at one of the chimps shuffling around near the glass.

“Woweee.” He stood unusually motionless and just took it all in. “Wowweee. Cooool.”

This sudden curiosity made my mouth drop open. I’d never seen him so engaged and he wasn’t biting his hands or anything. A slow-moving chimp shook his head, scratched an ear, and shambled past us, lazily heading for a rope swing. Another chimp stuck out his tongue and then flicked his hands in the air. Tommy watched them all with such focus, his eyes fixated on the animals.

He turned to me and pointed at one of the larger chimps sitting by the window. “She baby in tummy, Daddy.” He cocked his head at an odd angle, the way dogs do. “She chimpie baby in chimpie mommy tummy!”

“Really? You think so?” I raised an eyebrow and folded my arms across my chest.

“Yep. She baby.” He spoke so matter-of-factly as glimmerings of excitement shone in his eyes. “She chimpie baby. Chimpie in there and happy!”

“That’s using your words. I really like that.” I laughed and stepped closer to him. “But how do you know she has a baby?” The chimp didn’t have a protruding belly as far as I could tell, though I was far from an expert.

“Baby! Daddy! Chimpie!” He actually hugged himself and giggled.

I couldn’t believe it, this new eagerness of his. My breath caught in my throat as I stepped back, accidentally bumping into another onlooker, a short man with a full beard. Stroking his beard and scratching his head, the man shot me a nasty look.

“Sorry,” I mumbled.

The man replied with a grunt as he moved past us. The adult chimp that Tommy had pointed at stood up, screeched, then raised a smaller chimp on to its shoulders with the ease of an acrobat.

“Can you tell Daddy how you know?” I pushed back my Padres baseball cap as I gazed down at him.

But once again, Tommy said nothing. He brought his hands back up to his mouth and nipped the backs of them.

“Tommy, can we please not do that?” I shook my head, hoping he would listen.

Comments

So sad yet beautiful

It's a beautiful start.