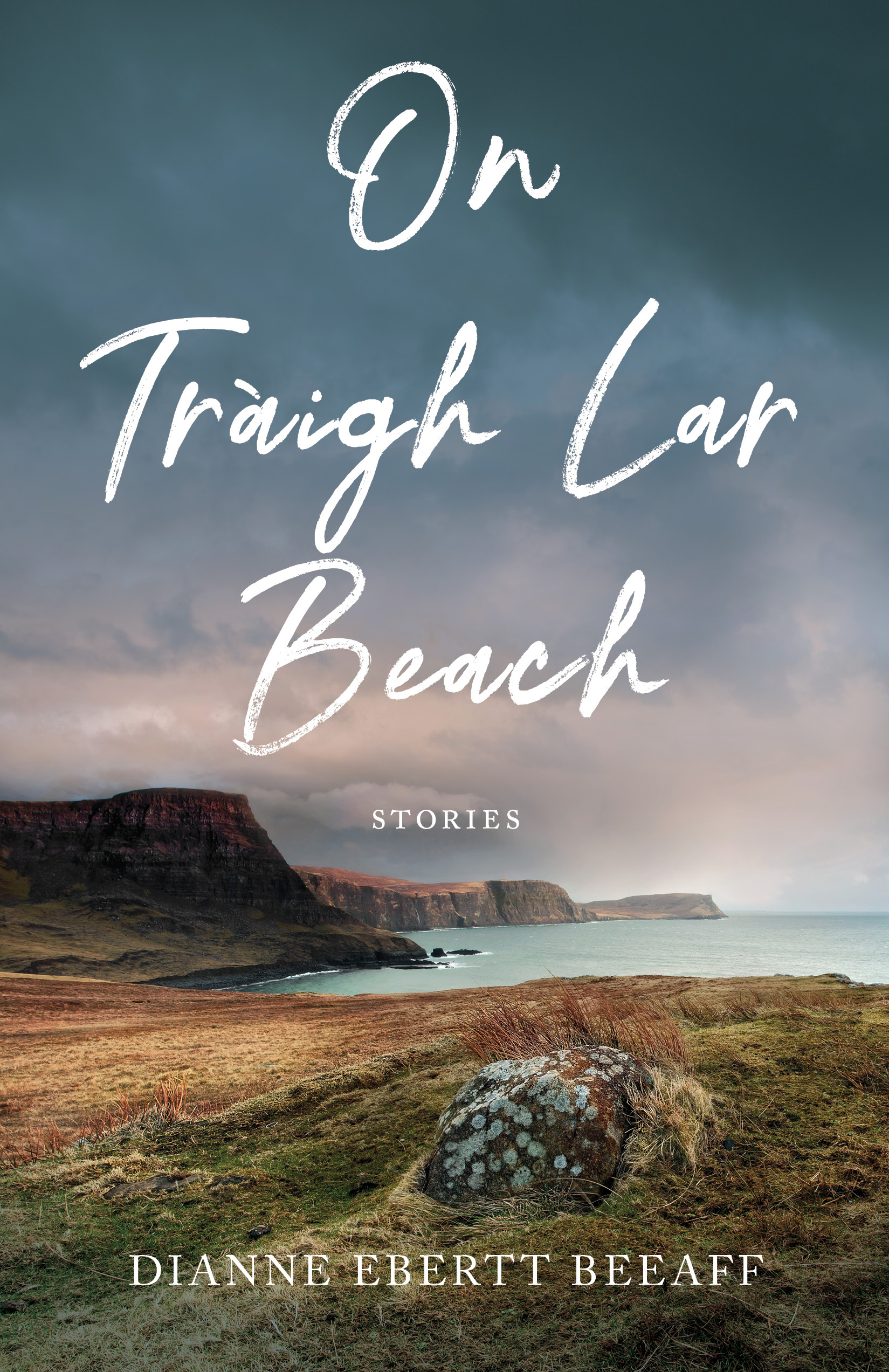

Prologue

TRÀIGH LAR BEACH is a small machair beach at the end of

Horgabost Sands on the west coast of the Isle of Harris in

the Outer Hebrides of northern Scotland. Machair is the

name given to the flat western coastal plain of Harris, its

beaches made of the shells and skeletons of ancient sea

creatures ground to fine sand by the ceaseless pounding of

the ocean. Breakers roll in with the roar of an oncoming

train, leaving drainage channels in pale blue-green gold and

symmetrical ripple marks above the high-tide line. Accumulated

sand forms wide white beaches and bordering dunes.

Calcium limes the dark acidic peat soils behind into rich

fertile grassland.

Standing on Tràigh Lar Beach, you can hardly feel more

solitary, more lulled by its stark beauty and breathtaking

peace. Black birds shoot in and out of nooks in the ancient

rock walls that line the road to Tarbert. Seagulls and carrion

crows hang motionless in the air. Cuckoos call from groves

of stunted trees, and hawks soar with ravens.

Flotsam, carried on the Gulf Stream from the New

World, has tangled in the seaweed on Tràigh Lar, dotting

the shimmering sand. During the summer months, the

machair lining its borders is adorned with a blanket of wildflowers.

Erica

Heather, a low-growing perennial shrub that dominates

the heathlands, moors, and acidic peat bogs of Europe,

was often called Erica—Calluna vulgaris—in traditional

references. Not a true heather, Erica’s mauve flowers

bloom on the machair in the spring.

RODEL, ISLE OF HARRIS,

OUTER HEBRIDES, SCOTLAND,

OCTOBER 3

The wide-faced clock over the bar here at the Rodel Hotel

moves backwards. Three o’clock in the morning posts as

9:00 p.m. I’m comforted by that, buoyed by the steady procession

of hours and minutes piling up in front of me.

On a fluke, my recent novella, Remembrance and Mania,

just won the faintly prestigious Comstock Award for short

fiction. As a consequence, I’ve had a two-book contract

flung across my shoulders like a length of chain mail.

I’m stagnant with fear.

I’m empty, deficient, inept.

I’ve nothing to say and no words to say it with.

On Tràigh Lar Beach

We’ve just settled into our self-catering cottage in

Rodel, at the southern tip of Harris, after a seven-hour drive

from Glasgow to Uig on the Isle of Skye, with my husband,

Greyson, at the wheel. We took the ferry across the Minch

to Tarbert this morning.

In our rental car then, in the wind and the rain, we

sailed to Rodel on the eastern shore single-track Finsbay

road. Harris had once conjoined with the Scottish mainland

but had slipped into the sea at the end of the last ice age.

Waterlogged bogs and black tarns lay about at every turn,

stabbed with the sharp bony intrusions of gray gneiss.

The evening before our Glasgow flight, I’d offered up a

thin slice of my soul in gratitude at the annual Comstock

Awards banquet in London.

“A book of towering achievement, equal parts critique

and passion,” Tawny Woodhouse, Comstock’s ebullient director,

pronounced on introducing “our grand prize winner.”

And though I broach neither process nor achievement

with any ease, Comstock left me spunky and bold. I soared

as though that gold-embossed curlicued certificate—“Erica

Winchat, First Place, Short Fiction”—had given me wings.

Wings now clipped by my own feelings of inadequacy.

RODEL, HARRIS,

OCTOBER 4

I woke up last night at about two o’clock. No moon, no stars,

and I could barely see my hand in front of my face. Outside

the bedroom window, the land and the sky stretched off in a

forever coal-blackness, just one shade darker than my own

shriveled psyche. I’m a fraud. I know that now. I can’t possibly

write anything of substance ever again. But Greyson

won’t let me wallow in it.

Late this afternoon, we sloshed through an old peat cutting

bog just off the Finsbay road. At the seaward end, we

climbed a hillock to watch storm-tossed waves heave themselves

at the cliff base below. Black-headed gulls hovered

above, and a brown-eyed fulmar exulted with two consecutive

flybys within arm’s reach.

About a third of a mile further on, a rock cairn marked

the site of a crippled broch-like tower, its stone walls now

reduced to a heap of rubble covered in thin brown grass. And

on the margins of the peat bog, at the far end of a small black

pool, stood a ruined croft filled with gravelly mounds of dirt

and old wire. Its yawning windows trumpeted a forlorn

emptiness.

Someone had lived there once, in veiled optimism. Or,

perhaps more likely, smothered in despair.

Over a game of pool last night, the Rodel Hotel barkeep

had told us the story of Donald MacDonald and his betrothed,

Jessie of Balranald. In 1850, young Donald—too

forgiving of the estate’s crofters—had been dismissed as assistant

factor in North Uist, an island to the south of Harris.

Jessie’s father pressed her to marry Donald’s mean-spirited

successor, but Jessie declined, and she and Donald set off

for the Isle of Skye. A storm-tossed night forced their ship

back to Tarbert where Jessie’s brother seized the couple and

imprisoned them in Rodel House—now the Rodel Hotel.

They escaped out a window in the Red Room and made

their way to Australia.

Surely even I could structure something warm and sentient

from such poignancy.

THE LOCHBOISDALE HOTEL, LOCHBOISDALE, SOUTH

UIST, OUTER HEBRIDES, SCOTLAND,

OCTOBER 5

We’re in our room, looking out across the rolling Minch to

Canna and Rum. We off-loaded in Otternish on North Uist

and drove south, arriving here just short of five o’clock.

After breakfast at the Anchorage this morning, a Leverburgh

restaurant dressed in honey-colored pine, we sailed

on the MV Loch Bhrusda ferry to North Uist. No ship was

scheduled for that time, but “sometimes the ferry just shows

up,” our waitress, Siobhan, said. Alert to the slightest shift

on the horizon, she’d spotted the black dot approach of the

Bhrusda well before anyone else.

For forty-five minutes then, the small boat beat against

the wind and the waves through one of the loneliest

stretches of the planet I’ve ever seen. Distant black islands

dulled with the rain. Plumes of spray nibbled at their base.

But sometimes, like the bright flash of a dream, sunlight

shimmered on the heaving sea.

The low groan of grinding engines, undertones humming

like an oncoming tank, sang above a frigid wind. Except for

the driver of a BP oil truck, who very quickly vanished,

Greyson and I were the ferry’s only passengers. No one

manned the bridge either, that we could see. If I could just

rouse my imagination long enough to create something compelling

from that.

THE LOCHMADDY HOTEL, LOCHMADDY, NORTH UIST,

OCTOBER 6

We left Lochboisdale just after breakfast. One of the most

intriguing things about the hotel there was a carved cherry-

wood armchair that stood in the hallway, all loops and

sculpted lyres. Though it had been there “forever,” no one

could tell us where it had come from. And what about that

Kilbride Shellfish truck abandoned just below the Neolithic

chambered tomb of Minngearraidh on Reineval Hill. How

did that get there?

Back here on North Uist, we negotiated a short, potholed

road to Langass Lodge, waiting in the car in a light rain as a

middle-aged Aussie couple walked their long-haired Siamese,

Skye, up and around the stone circle of Pobull Fhinn.

RODEL, HARRIS,

OCTOBER 7

At breakfast this morning in Lochmaddy, they played oldies

from the fifties and sixties, and Greyson and I had a slow

dance to Roy Orbison’s “Crying.” How apropos for my

numbed and moldering spirit.

On the way back to the Otternish-Tarbert ferry, we lingered

at Dun an Sticir, another ruined broch in a small back

tarn. Broken walls stood ten feet high in places, and the

remnants of a stone causeway lay visible just under the surface

of the pond’s crystalline water. Of course, we slogged

on over in our wellies, as fog slid down off the tops of the

hills and three white swans cruised the loch like the spirits

of long-gone tenants.

RODEL, HARRIS,

OCTOBER 8

Stories as thick as clotted cream spring out of these Harris

peat bogs. The church next door, for instance, St. Clement’s,

dates back to the sixteenth century. Effigies of medieval

knights, set in the interior walls and bordered with Celtic

knots, offer no shortage of possibilities.

And sheep. Sheep stand everywhere. Never troubled by

wind or rain, they idle in roadways, oblivious to oncoming

traffic, finally moving off, paunchy Tribble bodies on spindly

legs. If the incessant wind were somehow sapped of its energy,

grinding sheep jaws would fill the void.

Later on, just up from some glassy loch off a skinny interior

byway, we stumbled on an overturned lorry lying in

the peaty muck. A half dozen young people, most of them

with Cockney accents, had gathered round in cable-knit

sweaters, blue jeans, and Wellington boots, and collectively,

we helped them work an old upright piano fallen from the

van onto a flatbed truck. Who was moving to such wilds

from England?

RODEL, HARRIS,

OCTOBER 9

Greyson and I played golf at the Isle of Harris Golf Course

this morning. Two congenial Scotsmen, on playing the third

tee, lent us their clubs. Between intermittent rain squalls,

loitering sheep, and rabbit-warren sand traps, we finished a

solid round, the sea a thundering backdrop.

I’ve been scouting the wide white sands of West Harris

for inspiration. Flat and firm, they’re overflown by hawks

and ravens. The marram-grass dunes and plains behind are

called machair, pocked with rabbit holes and patches of cultivated

grains, small sheaves tied up with straw. Redshanks

bob among the wildflowers.

Just to the west of Seilebost Sands, the farthest machair

from Rodel, lies our favorite beach—Tràigh Lar. Tràigh

(pronounced “try”) is Gaelic for sandy, and Lar means floor.

When the sea is wild and blue, Tràigh Lar is astonishing.

Even with high tide, waves continue to shatter on Tràigh

Lar in a frothy mass.

To the left, the empty Toe Head peninsula extends three

miles into the Atlantic, capped by the moorish hill of

Chaipaval, and joined to the mainland by a strip of machair,

with a sandy beach to either side. The island of Taransay

lies to the right. And between them—emptiest of all—are

the distant deserted islands of St. Kilda. On the hillside

above Tràigh Lar, the MacLeod Stone rises tall and thin, one

face covered in crusty pale-blue lichen.

We wandered back to the roadway through blankets of

limpet shells deposited in a tangle of seaweed and flotsam. A

cigarette lighter, a jar of pickled onions, the handle of a

child’s bucket, an empty ketchup holder, a rock-concert laminate

badge, a green plastic laundry basket, a packet of

arthritis pills . . .

Now where did these come from?

Melody

Rose

(An Empty Ketchup Holder)

White Common Eyebright—Eurphrasia nemorosa—

latches its roots onto nearby plants for sustenance.

HE HAD A FACE LIKE polished driftwood. Sculpted. Ageless.

So fluid and graceful, it was almost courtly. When he

danced, his thin old-man arms dangled at his sides and he

shuffled across the pavement on crimped legs. Someone

from the stage, without looking, called him “Pops.”

“Give it a rest, will ya, Pops?”

But the old man’s name was Walker, and some of them

up there knew it.

Old Walker crooked a finger at a little boy in red passing

by—a chubby all-smiles toddler in an oversized baseball

cap and bare, dirty feet. “One small dance, eh, big fella?” He

dropped down, bent almost double, wagged a bony finger in

the boy’s face, and winked. “Oh, come on now.” His voice

rasped like a file over the music from the stage, and he

coiled the finger over his palm. Once. Twice.

All afternoon, the little boy in red had circled the seated

Melody Rose

folk-festival crowd, wobbling haphazardly up this side and

down the other under the attentive but distant eye of his

father. Now, in front of the old man, he lurched to a halt

and stared at the creased and empty outstretched hand. His

hazelnut eyes gleamed like buffed sandalwood, and he

worked his small pink mouth into an extravagant pout.

“Jason!” The boy pitched forward with the sound of a

coarse male voice from out of the crowd. “Jason!”

Jason pulled a stubby arm from behind his back and

thrust it toward the old man just as his father, a craggy

young man in tattered Levi’s and a stale blue T-shirt,

swooped in and plucked the child away.

“Time to go, sport,” he said, hoisting the little boy up into

the air, where he hung over his father’s head, suspended by

two freckled arms. And then, vicelike, his chunky baby-fat

legs clamped to left and right on the man’s shoulders.

“Time to go, sport,” his father said again. And, without a

single glance at the old man, he lumbered off into the crowd

like a freighter putting out to sea.

Old Walker unfolded his bones in the manner of old

men everywhere and swayed over the concrete slab fronting

the stage, like an empty skiff in a sea breeze. Above him, a

dark-haired, pasty-faced man in a ruby-red cotton T-shirt

and thick black-rimmed glasses stepped forward to introduce

the next act.

“If y’all are lucky”—and the old man was not—“you saw

this next group at Voodoo Mama’s last Saturday night,” the

man on stage announced.

A rowdy wave of approval rippled through the crowd as

three booted and bearded young men with instruments of a

bluegrass nature strolled to the center of the stage.

“Please welcome, from right here in Orleans Parish,

New Orleans’s very own Catfish Bayou String Band.”

Almost at once, the three men in boots and beards be-

gan