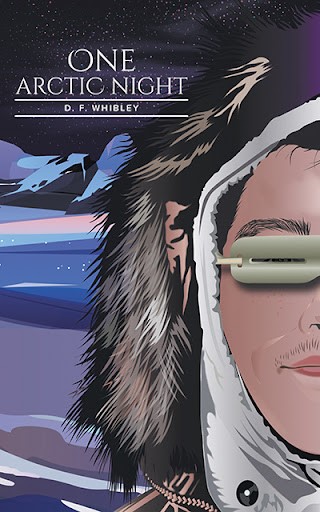

This is my first novel, and it is based upon years of observation I noted whilst travelling the Canadian Arctic.

The Canadian Northern aboriginals are called Inuit. They are a proud culture with amazing traditions pretty much unknown to the rest of the world.

My book opens up their culture to outsiders.

Readers will discover that a 17-year-old Inuit boy has the same fears and concerns as a 17 year old British lad. They will also learn what day to day life is like in a typical Inuit village. Where do they get their water from? What is their health care like? What is it like inside their homes?

They will also experience racism at its core while dealing with the incredible fury that nature has to offer.

This book is self-funded yet it has won two awards (one Canadian and one International) and is a Special Mention in anther contest.

I hope you enjoy it.

As he lay in bed, Panuk would often point his toes downward and stretch as hard as he could, hoping it would help him grow a bit taller.

Panuk was proud of his Inuit name, which means one who is strong, but he hated being so short.

When he was younger, his grandfather would often tell him the story of the Tuniit—the giants of the land. Panuk wondered why he couldn’t be a Tuniit. He daydreamed of showing up at school as a giant and becoming a basketball star and getting drafted by a pro team. The Tuniit were strong and fast and hard to catch. Panuk knew that, just like the legends of the Tuniit, his dream would be hard to catch too.

He sat up on the edge of his bed and held his legs straight out.

Checking them out, he was glad that the infection around his ankles had cleared up. The antibiotics the nurse at the nursing station had given him last summer had certainly helped. He’d had so many mosquito bites around his ankles that they had become infected.

He loathed the mosquitos that arrived in droves in the summer. He would often wonder how God could have created such a creature. If he heard the high-pitched buzz of a mosquito in his tent or room, he would not be able to sleep until he got rid of it. Many a night, he had to leap out of bed and turn his light on to hunt for that little nuisance.

He continued to look at his legs. One metre, six centimetres isn’t going to get me a spot on any pro basketball team, he thought. He sighed as he let his legs back down. Then he picked up the mirror by his bed and stared at his face.

His dark eyes crisscrossed the mirror and settled on his haircut. It’s time to get Mom to cut my hair, he thought.

He then looked straight into his own eyes. He liked what he saw. He believed he was good looking and wondered if some day he would have a girlfriend. He smiled and checked out his teeth. So far, so good, he thought. He had never been to a dentist, but he hadn’t yet suffered any toothaches as his cousin Aklaq had. He was thankful.

He noticed a band of fuzzy hair growing over his upper lip. He would have to ask Dad about getting a razor soon. He had been using his dad’s occasionally, but he realized it was time to get his own. Putting the hand-held mirror down, he stood and looked at himself in the full-length mirror on his wall. He raised both his arms and made his biceps pop. Hauling gear for Dad’s guide business had left him muscular and lean. He laughed again, wishing he was a Tuniit.

He lay back down on his bed.

Panuk scanned his room, looking at the white ceiling, the white walls, and the white furniture. He thought it interesting that his bedroom was like an extension of the scenery outside. He stood up again and looked out the window to view the white expanse that surrounded his home.

Flopping back onto his bed, he decided that someday, he would save up to buy that nice cherry-red wireless speaker he saw at the Co-op store in the village. It would add some colour to his room while he listened to his favourite songs. The only other colourful objects were his trophies and medals, and the blue-and-red ribbons hanging over the trophies that he had received at hockey tournaments.

While looking out the window, Panuk had noticed Toklo playing hockey on the path near his house. Panuk quickly dressed so that he could join his friend.

As he turned and walked through the house to head out the door, he noticed his father sitting on the couch, holding his stomach in pain. Panuk asked his dad what was wrong?

His mom interjected.

“The nurse thinks it’s kidney stones and said he should fly to Iqaluit for an operation,” Mom said. “He will be leaving tomorrow morning.”

Panuk had a sinking, sick feeling in the pit of his stomach. He loved his dad and the thought of his dad being sick was scary for him. “What’s going to happen?” he asked.

Panuk’s father called him over.

“Son, I will be away for a few days,” he said. “I need you to guide the visitors when they arrive tomorrow. They have already paid for their entire trip, and there is no way I can cancel after they have travelled so far.”

§

Panuk’s dad worked as a guide for tourists who came to the village to hunt for caribou. He owned the business, but in reality, it wasn’t much of an enterprise, as he was the only employee. He did, however, appreciate the chance to do something he loved and get paid at the same time. It was perfect for him.

Panuk found it strange that the hunters would never want the meat, but instead were only interested in antlers. It didn’t bother him, though, because he knew Dad would keep the meat and share it with other families in the village.

“Let them take those silly antlers,” Dad would say. “At least, we will have full stomachs tonight.”

Panuk preferred the tourists who ventured out onto the tundra with Dad to take pictures rather than hunt. Those people were more understanding of Inuit tradition, which held it sacred not to waste food sources.

Dad offered the tourists three ways to travel out of the village to hunt the caribou.

One way was by snowmobile. Panuk loved this method. He enjoyed the freedom of gliding across the tundra, the wind blowing in his face, the sun glinting off the snow. It was as though he was in another world and he would quickly forget about any problems that might be bothering him that day.

The second method was by dogsled. Panuk hated this. He knew it was the traditional way, and he did love the fact that his grandfather had travelled this way many years ago. Still, he dreaded the hard work that went along with it. He had to harness ten dogs, few of whom were ever cooperative while getting hitched. He also had to prepare many fish to feed the dogs. And the dogs always had to be encouraged, by whistling and hollering, to run. There was no chance to relax and daydream while dogsledding. It was so much easier to use the snowmobile.

The third way was by riding a four-wheeler. This manner was perfect in the spring, when there was not enough snow on the ground for either the dogsled or the snowmobile.

No matter which method was used, a qamutiik loaded with gear had to be towed. These large wooden sleds could hold lots and lots of equipment.

Panuk was excited to help his father but soon grew apprehensive. “Are they going to hunt or take pictures?” Panuk enquired. “Where am I going to guide them?”

His father explained, step-by-step, where to bring the men, where to set up camp for the night, and what to do if they were able to get a caribou.

“Dad, do they want to go by dogsled?” he asked. Panuk held his breath, hoping the men had chosen snowmobiles.

Dad smiled, knowing how much his son hated handling the dogs. “It’s your lucky day. They have chosen to hunt using snowmobiles.”

Panuk let out a sigh of relief. He knew how much trouble he would have had trying to control ten dogs, especially without Dad there to help.

As his father lay on the couch, his mom brought Panuk outside to one of the qamutiiks, the sled they were going to use to carry the gear. She showed him all the different items, including the tent and massive bear skins and blankets that he would be bringing on the trip.

“Mom,” Panuk said, “I don’t need all this gear. Who needs bearskins? I will be in a tent with a down sleeping bag. There is no need for all this old-fashioned stuff.”

Panuk’s mother shook her head. “You must carry all of this with you in case of an emergency. More than once, your dad has been happy that he brought all of the gear with him. Remember last year when the four-wheeler broke down near the coast?”

Panuk nodded and agreed to take the whole load. The other sled, the one the Southerners would be hauling, would hold the boxes of food, as well as the hunters’ gear and several jerry cans of gasoline. The food would be cooked and kept warm in individual boxes. His mother also reminded him that he would be taking the satellite phone with him.

In the wilderness of the Arctic, there was no cell phone service. Some larger villages had a cell phone tower, but once outside the village, the signal was always lost. To stay in contact with the village, most hunters carried a satellite phone. They were very expensive to use, so they were usually deployed only for emergencies.

§

Panuk was proud to be Inuk. He felt a special relationship with the land around him. His father had taught him about hunting and surviving in this cold and barren place. He loved his excursions with his dad, who was the silent type. On trips that lasted days, he might only say a few words, usually to point out tracks in the snow or explain the best ways of tracking various animals.

But that night, Panuk had trouble falling asleep. He was worried about Dad, about meeting two strangers, and about the heavy responsibility of taking them far out onto the tundra alone. He had gone a few times with Dad and other tourists, but this would be different. He would be doing it alone.

Panuk knew his parents tried their best to instill in him the Inuit way of life. If they had given him this responsibility, they must’ve believed he could handle it.

Panuk’s parents had met many years earlier when Dad, as a young man, visited Cape Dorset. He had brought a load of beautiful jade-coloured soapstone to sell to the village carvers. Mom was originally from Wolf Inlet and was raised in a traditional family. She learned at an early age all the domestic duties that a young Inuk girl would need to know. She also was brought up knowing how to fish and hunt.

It was in Cape Dorset where Dad and Mom first got to know each other. Later, Mom would explain to Panuk that his dad was the first person she had met in her age group who didn’t smoke tobacco and that this had made him stand out from the crowd.

Marriage in Inuit communities was a partnership. Men, who often travelled far for food sources, needed to know how to cook and even sew in case of a problem while away, and women had to learn how to hunt and set up a campsite in case their husbands were away longer than expected.

Panuk felt his mom was oh so smart. She could cook up a delicious meal in a flash, but she could also change the oil in a snowmobile motor without balking.

His dad was also multitalented. When away hunting with Panuk, he would quickly make the meals, pitch the tent, and organize things to make life comfortable out on the tundra.

His parents’ wedding took place in a Christian church in Iqaluit, and the young couple had moved to Pangnirtung fifteen years ago to start their guide business. Pangnirtung was on the northeast side of Baffin Island and offered the newlyweds an opportunity for their dream of raising a family in traditional ways to come true.

Along with his parents, Panuk lived with two sisters and two cousins. Like all parents, Dad worried about the future of the Inuit culture. He was raising his children to experience the life and even some of the hardships that his parents had lived. He wasn’t sure his kids would even stay in Pangnirtung. He knew that Akna wanted to go to university and become a nurse. Little Nuliajuk had mentioned that she wanted to be a movie star, and Panuk had talked about going to college in Thunder Bay to become a writer. He had already sent in his application.

Things were changing for the Inuit and their way of life. Dad knew that. More and more ice melted each year. Many of the village Elders had noted there were fewer polar bears in the region.

Before going to bed that night, Panuk had overheard his parents talking in their bedroom.

“If we lose much more ice each winter, no tourists will come,” Dad had said. “We might