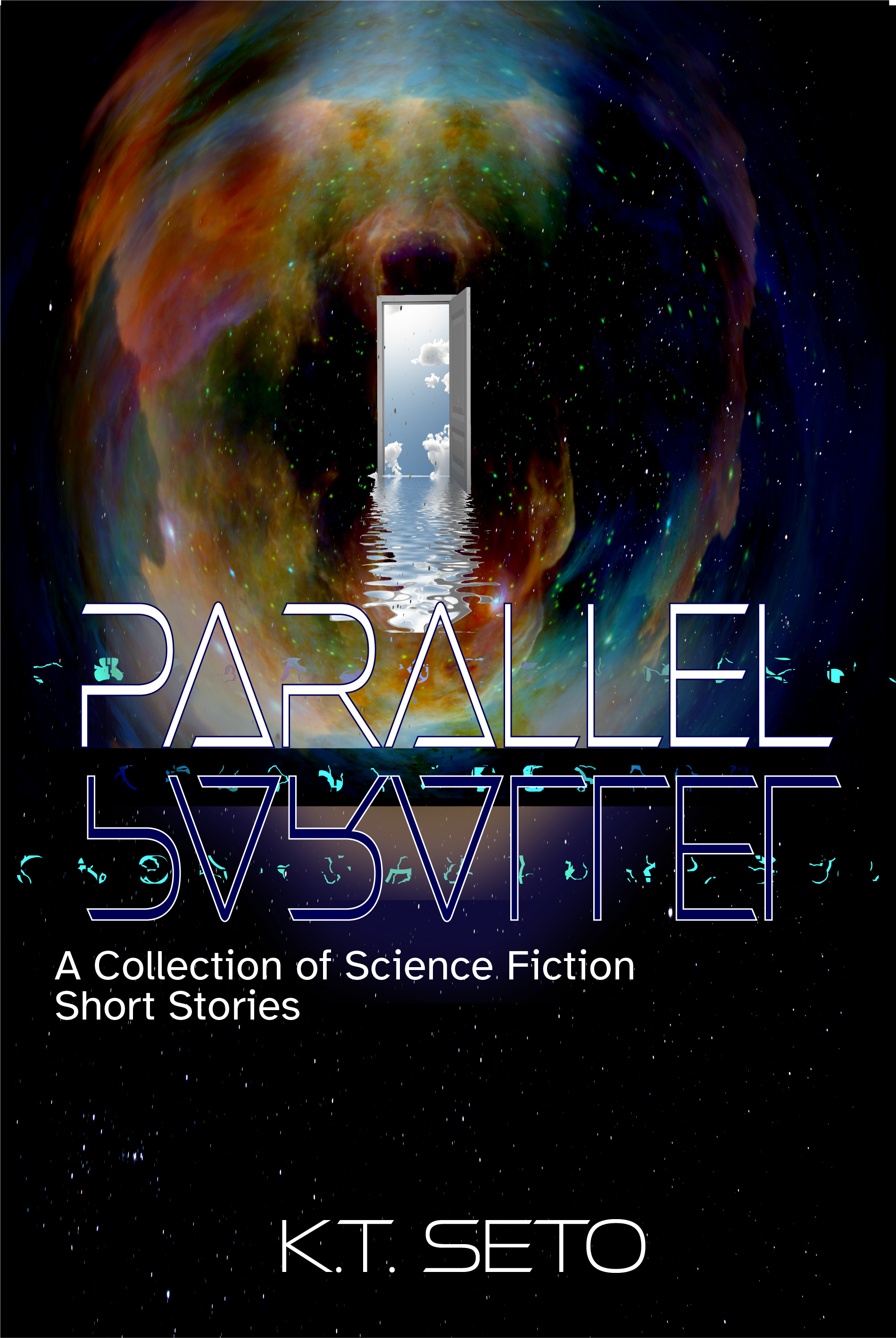

Parallel: Anthology Of Short Stories

A Collection of Science Fiction Short Stories

K.T. SETO

PART ONE

ODDITIES

As a Speculative Fiction writer in the 21st century, you have to be willing to take risks and do it all. Which means you have to get very comfortable with the marketing side of things. Most writers take that as explicit instructions to write a blog. While I did eventually try my hand at this, I remain skeptical as to its use or value as, ultimately; I am a storyteller not a reporter. I love to write stories. To build a following, I started writing short stories and putting them up for free on a site I found that is perfect for that. It is a way to play with ideas that might or might not work in longer form. The original intention of my works on the VM site was to free myself of expectations and just create hoping someone will enjoy. All the stories in part one are bits that don’t fit. Odd tales of ‘what if?’ I initially published the first four on the VM site. The last one, “Apoptosis”, appeared originally in a horror anthology called Nightmare Whispers. I readily admit sometimes my imagination is quite disturbing and rather off. Which I feel is the perfect reason to inflict it upon the general population. Why should my friends be the only ones who get to be confused and disturbed by me?

2

The Ark

Utopia isn’t a place, really. It’s an idea. Or, better yet, an ideal to seek. It’s ubiquitous because it pops up in many ways throughout history and in myths and legends. Through the ages we have always had stories that allude to some great perfect moment coming. The dream of it is alluring. As a child, I always hoped it could happen. I read the classics and watched the old speculative fiction movie streams from a young age. The ones where humans imagined what the world would look like in a future without all of life’s petty problems. Where everyone had come together as a species and made great things happen. Nothing I read or saw ever convinced me that such a place, such an ideal, could exist. Because I knew people. The people around me and the history of our countries with their selfishness and wars. People, even when they have everything they could ever hope to have or wish for, never seemed to settle down and have that moment. Something spoils it, looms on the horizon, or festers underneath. Yet, some part of me still hopes despite the constant stream of evidence proving that Utopia is impossible. Which makes this meeting even more tragic, because we have solved so many problems but not the most basic—human nature. The light in the conference room hurt my eyes, but I didn’t dare look away from the table for even an instant. Too many of the dignitaries gathered there would take even an extra blink as a sign of something. What, I didn’t know. I could barely keep up with the intrigue in the room and the petty games politicians still played, even in this enlightened age. There were three dozen of us in the room, seated in amazingly comfortable chairs around the large round table. The gleaming surface of it resembled the ancient hand-carved Scandinavian woodwork of the late 20th century. Of course, it wasn’t wood. No one has used something so precious for furnishings in over a hundred years. They’d grouped us by position rather than by region, which is why I and the other scientists called upon to testify sat together. It meant I knew the people sitting on either side of me. Doctor Ito Akari, a cytogeneticist from New Tokyo, sat on my right, her eyes moving around the room and back to her table display where a series of formulas shifted and flowed in a manner that told me she was still working on the problem even as the politicians sat before us pondering solutions. On my left sat Doctor Yonas Gebremariam, climatologist from Kasai, one of the two remaining countries in West Africa. He watched the room with heavy-lidded eyes that to the unschooled might seem inattentive. Yet I have known Yonas for over twenty years and there was no one who could sum up a room in a glance the way he could.

“The people on the Utopia Project chose to leave; I don’t think there is any need for discussion here,” a fair-haired man said from the end of the table. I couldn’t see his ID badge from where I sat and didn’t bother queuing it up on my table display. If he was important I would already know his name, though he looked vaguely familiar.

“Are you actually suggesting we leave them to their fates?” the man next to him said, and I leaned forward a bit, the urge to rub my eyes becoming unbearable. This one I knew just by the sound of his voice: Pieter Dragovich, the ambassador from the Siberian Block. They hadn’t bothered to send their president, their country’s stance on the issue being well-known. It was doubtful that anything said here today would change it.

“Isn’t that what they did to us?” the fair- haired one said waspishly in reply. No one answered him. In all honesty, he’d said what we’d all been thinking. Deep down we all felt like they deserved it. Let them rot, the small, mean part of me said. They didn’t care about us; about anything. Guilt assailed me for the thought, so I cleared my throat in preparation to speak to the room at large. After all, they’d made me spokesperson. Drawing straws, an archaic and egalitarian method of choosing the sacrificial lamb to toss to the wolves so to speak.

“That is not who we are, not who we have become as a people. Where is the compassion and integrity you all preach?” I said, pushing down that tiny bit of resentment.

“Don’t toss out platitudes and campaign slogans, Doctor King. We are talking about an entire ship full of the worst parts of humanity. Every person living there was so firmly entrenched in the past that they chose to flee rather than stay and make the hard choices necessary to save our species.”

“I know what and who they are.” I didn’t raise my voice but couldn’t entirely keep the anger from my tone.

“We asked Doctor King and the others here in an advisory capacity. We don’t need emotion or opinions, we need facts. If no one has an objection, why don’t we revise the order of our schedule and allow Doctor King to provide the findings of his team before continuing this discussion.”

I turned to look at the British Prime Minister and gave her a nod of recognition for her support. Her knack for diffusing difficult situations was why she’d remained in power for so long.

“Very well,” I said looking back at the man who’d first spoken. I pulled up his name on my display, dismayed to find that I couldn’t dismiss him out of hand.

“Mr. Vice President, you are correct; their ancestors did choose to leave, but they didn’t. The Ark has been in orbit longer than most of them have been alive. Maintained and updated by AI that gives them a filtered stream of information about what is going on here on the surface. We have never once offered any of them the chance to make a different choice. From their orbit above the Earth, they can see the changes we have wrought in their absence. They are not completely isolated. They know the world is not the same one their great-grandparents left.” I ran my gaze around the room before continuing.

“However, all of this is moot. The fact is, they have lived too long in space to return. We have run all the numbers and projections. They could not stand full gravity. It would kill them all within weeks. Their request for resettlement is not possible. Our only option is to offer them help with repairs.”

The silence that filled the room after my statement didn’t surprise me. I, and the other five scientists who’d led the teams—studying this problem since the Ark sent out the SOS six months ago—had known our findings would cause issues.

“If their own AI can’t repair things, what’s to say anything we have will be any more effective?” The Chinese Prime Minister’s voice was soft but carried around the room despite the lack of amplification. I looked at her and suppressed the urge to sigh. Did no one read the reports given to them?

“What they need is attainable with our current technology. Theirs is still several decades behind.” Doctor Ito interjected without taking her eyes off her display. It was clear something there worried her, and I wished I had a moment to confer before dealing with more bureaucracy.

“How is that even possible? Mandatory updates being what they are.” I looked over at the American Vice President again, stifling the urge to snap at him. Reading in the 23rd century was apparently not common among the ruling class.

“The creators of the Ark intended their system to be self-sustaining to better withstand intrusions by hackers and any other outside forces. They didn’t want us to be able to sabotage them.”

“Why would anyone left behind sabotage them? They sought to escape the destruction of their own making. They designed their Ark station to provide a new world to replace the one they’d destroyed.” There were several smothered laughs around the room in response to this statement. I waited a beat then continued.

“We can send a ship and supplies to them and make the repairs. It will save their lives, and the Ark will be able to remain in orbit for another fifty years.”

“So, their refuge is to be their prison?” PM Sussex asked, and the Vice President made a low sound I chose to ignore before replying.

“This was a choice their ancestors made, not a punishment for their crimes. It is not as if they lack for anything. They spared no expense in the creation of the Ark, the equivalent of hundreds of trillions of dollars,” I said, pulling up the specifications of the Ark and instructing the computer to display them on everyone’s tablets.

“It is wealth they could have used to fix this planet in a few years rather than decades. They chose to leave. It was the height of selfishness, and truly short-sighted. Some might say that they should go to prison for what they did. I am not among that group. It is only human nature to be concerned with personal well-being. And those who committed the crimes are long gone,” Yonas said, and I saw several people jump in surprise. Clearly some had thought him sleeping. I suppressed a smile and pulled up the next slide.

“You said fifty years? Then what?” a voice from the back of the room asked, and I turned to face the speaker even though they were too far for me to see.

“We have fifty years to develop a means for them to either return to Earth or abandon them to their fates.”

“So, we fix the ship and kick the problem down the road to our successors,” the voice replied, and I shrugged.

“You asked us to find an immediate solution. This is the best we can do.”

The meeting ended after another hour of pontificating and disagreements that changed nothing. My testimony had negated the need to decide much more than who would deliver the news. I remained seated as the important people began to leave, watching Doctor Ito scan her display and shake her head.

“You didn’t add anything,” I said quietly.

“Because they’d never go for it. I have no patience for politics, you know this.”

“But you have something,” I pressed, and she nodded.

“It’s not ideal.” I waited and she leaned close, looking over her shoulder to keep others from listening in.

“The children. If we brought them back, we could potentially reintegrate them.”

“But not the adults,” I said quietly.

“No one who has hit puberty.” We exchanged a look and then I nodded.

“Better not to tell them.”

Red House

“A candle is burning in the window of the abandoned cabin. You know, the one in the woods?” The statement echoed in my ears. I couldn’t speak for a full minute. My throat just closed up.

“You know we’re not supposed to go in there, right?” I asked when I could speak again, and Evan nodded. “Do you know why?” He shrugged but didn’t answer. He couldn’t understand my reaction, I guess. He’d said a candle burned in the window and I’d dropped my mug, spilling my half-caf all over. Because every word in his statement scared me. Like it scares me every time I think about what happened. Starting with the woods. They were the second reason they’d abandoned the cabin. Well, abandoned it here. The great red forest.

In the beginning, terraforming Mars was an idea that appealed to everyone, but creating trees and other vegetation that survived and thrived in the domed surface colonies required a level of genetic manipulation and investment that governments seldom want to sustain for long. So they left the vegetation to its own devices, and the woods had evolved into something only vaguely related to their Earth-native counterparts. Every so often, someone else swept in and tried to tame things, but they always gave up.

The NAA—North American Alliance—started this. It had been their idea to model the new forest after Yellowstone—the first of the fully restored national parks on Earth. They’d done a full study of which plants could survive here, then arranged everything according to their plan. Unfortunately, the latter part of their plan included installing the cabin. The main reason they’d abandoned everything.

They’d wanted an authentic forest ranger cabin. If they could have put a bowtie-wearing bear in there, too, they’d have been happy. Someone located an abandoned cabin they considered authentic enough and in good enough shape to disassemble, transport and reassemble, and stuck it in the middle of their newly planted vegetation, furnishing it with high-quality reproductions of early 19th-century pieces. Perched as it was amid the rust-colored trees and spindly foliage, it loomed in a way that put the final nail in the coffin of the project. It never looked remotely welcoming. Not at all. The combination of the two made certain that no one would ever want to go into the new forest again. Much like the surrounding forest, they had left the cabin to its own devices for far too long. The structure was intact, but the appearance had fallen victim to neglect; both on Mars and back on Earth. They’d repaired the windows, but it hadn’t mattered. No one who entered the cabin ever wanted to set foot in it again. And after last time, they’d told us to keep out officially.

“I suppose I should tell you what happened. You know, the other time it was lit so you understand,” I said, and he shrugged. I closed my eyes and nodded, resigning myself to revisit the nightmare, on purpose this time, because the candle was lit. Understanding is part of the ritual, part of what has to happen.

“You know how the cabin got here, right? How the government brought it over with the first permanent settlers? How they worked to get it right, down to the smallest details. Like the candle. It’s a fat, hand- molded column of paraffin created using the ancient modeling methods. It sits in a replica lantern on the window ledge as part of the art installation with the painting of the lost ranger. Until that night, no one had ever lit it. Or even thought it could be lit. But like everything commissioned as part of the project, the artist contracted to recreate the ancient device had worked for authenticity, so it was a real candle in a real lantern. Or as close as anything on the Red Planet can come.” I looked at the poor kid whose job it was to make sure no one trespassed in the forest at night. It was fifteen minutes after midnight. With a start, I realized it was around the same time we’d seen the candle the night it happened. We use the same clock on Mars, but our hours are longer to help better sync our time to the home-world. He was humoring me. I could tell he couldn't care less about anything other than if he would get in trouble because someone had gone in after dark and messed with things.

“It was a night like tonight, around midnight. The candle was lit so the kid on patrol duty, his name was Willard, came here to tell the MOD. The two of them called me and I agreed to meet them there.” I shook my head. “You know how the forest is at night. It gets funny. The things that live there, GM mammals, birds that escaped the aviary, and the muggies, all come out to play. The noises they make are enough to make your blood run cold. They assigned me a patrol on the other edge of the forest. You know Gamma quadrant, so I couldn’t see or hear anything until I got closer. When I did, I heard the muggies hum.” I swallowed and skewed my face.

“That’s what that is? I heard the humming, but I couldn’t tell what was making the noise or where it was coming from. Kind of creeped me out the way it seemed to come from everywhere and nowhere,” Evan said, sliding into the chair on the other side of my desk.