Author’s note: In order to pare a 600-page book down to an approximately 3,000-word submission, I’ve skipped past the Introduction, provided the “How to Read This Book” section to explain the book's contents, then jumped ahead to portions of a couple of chapters after the main subject has died. The book primarily revolves around Charles Watts, a Gray’s Inn London law clerk turned American prairie pioneer. Charles’ seventeen years of letters to his brother Edward, in London, are transcribed and provided with their backstory in Part I of the book.

**

How to Read This Book/Section Descriptions

To tell of the research first and then provide the story that unfolded? Or just lay it all out in chronological order? I have chosen the latter because it helps illustrate how one’s decisions and actions may significantly impact and inform future generations.

But let’s get one thing out of the way right now: there is no perfectly satisfactory way to read this book, which is part nonfiction history, part family history, and part research documentation. Any reader with the slightest interest in American or British history will be rewarded with some of the content within these pages. Any genealogist will be interested in seeing the results of such a long effort. Some parts of this book may be of enormous interest to you. Some may be of little interest. Read what you like, don’t read what doesn’t interest you, and we shall never speak of this again.

Part I revolves around four primary figures:

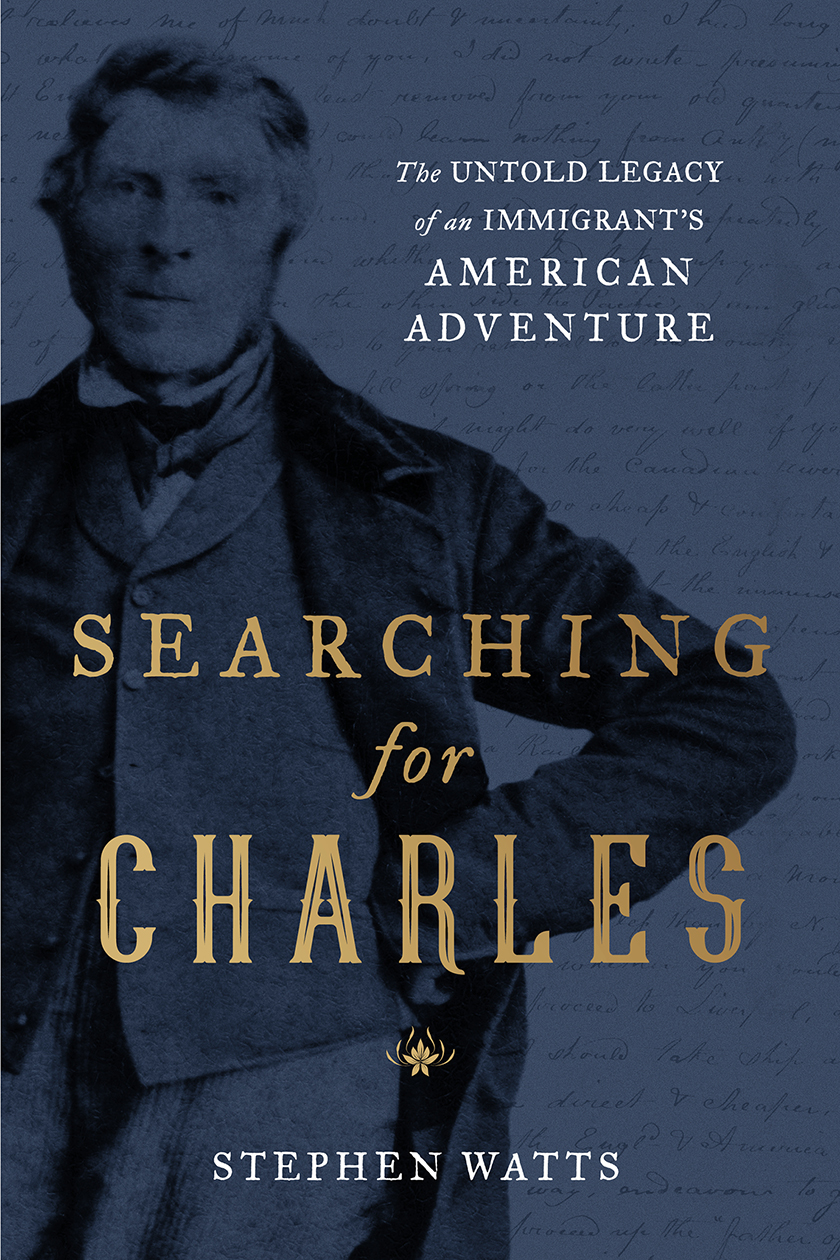

Charles Watts: My great-great-grandfather emigrated from London in late 1835, ultimately settling outside LaMoille, Illinois. His surviving correspondence served as the inspiration for this book and is the driving force behind Part I.

Charles Wiggins: Eventually joining Watts in Illinois, Wiggins was the stepson of Mary Watts Wiggins, who was the sister of Charles Watts. Charles Wiggins’s father, William, and his stepmother, Mary, sent Charles Wiggins to Bureau County, Illinois where he initially lived with Charles Watts before striking out on his own.

Mary Ann Thurston: Mary Ann became the wife of Charles Watts. Her father, Flavel Thurston, was the son of an American Revolutionary War soldier. Flavel brought his family from Ohio to Wyanet, Illinois, and their travels and experiences were recorded years later in a descendant’s memoir.

Edward Lowe Watts: After many years of unrelenting encouragement by Charles, Edward emigrated with his wife and their two children who were still at home. The Edward Watts family lived with Charles and Mary Ann before establishing their own farm in Peru, Illinois.

This text is centered on the life of Charles Watts. Watts’s letters are typically lengthy and detailed. During the transcription process, I frequently had to stop and research people, places, and events that were mentioned. Even after multiple readings of the letters, I occasionally caught something I had previously missed and struggled to sort out the frame of reference.

I needed to create narratives that provided the background information, context, and Charles’s relationships with the letters’ recipients and the people named within. How to present these narratives became a new challenge. Should I place each of them prior to the letter to make the letter itself more comprehensible to the first-time reader? Or should the narrative follow as a supplement to be read only after one has worked through the transcription? Another alternative was to provide supplementary information in line with the text of the letters so everything could be read in one pass.

None of these options seemed ideal. I chose not to add background or context in line with the transcriptions because I felt it would be too distracting. Placing the explanatory narratives after the letters would require the reader to constantly flip back and forth to understand the letters’ contents. One of my primary purposes in writing this book was to “tell the story,” so that is how I structured Part I. Before each letter, I provide the narrative, which includes the background, context, explanations, and relationships that will make the letters themselves an easier read.

All transcriptions and quotes are presented with spelling, punctuation, grammar, and corrections as they appear in the original documents. Letter transcriptions are italicized. Improper original document preservation techniques have taken their toll over the decades. Transcription passages that contain question marks within brackets indicate indecipherable or missing words or sections. The number of question marks indicates the approximate number of illegible or missing words. Occasionally, a string of question marks is interrupted by one or more legible words within the brackets.

It can be difficult to keep track of all the names and relationships in Part I, especially since some people have the same first names. It may be helpful to park a bookmark in the “Family Trees, Photographs, and Illustrations” section of the book because the family tree charts will need to be consulted often.

Part II is a comparatively shorter section in which interested readers may learn more about some of the families mentioned in Part I and what became of Charles and Mary Ann’s descendants.

Part III is the story of my father’s and my research. On five separate occasions, I considered my work to be finished. Four times in a row, I was proven wrong as I stumbled upon even more discoveries. I knew I could relax the third time I was “done” because we had found what I was searching for all those years. Yet, one bothersome abandoned trail remained. An impulsive last pass paid off in a twist more surprising and fitting than I could have imagined and which allowed me to end my active research—for the fourth time—knowing its conclusion was truly worthy of decades of work by two generations of Charles Watts’s descendants.

Again, I was wrong. In the process of writing this book, I retraced old steps and launched new lines of inquiry, resulting in several new discoveries. “Fifth time’s the charm,” no one ever says, but it worked for me.

“Family Trees, Photographs, and Illustrations” follow Part III. The family trees are presented in the optimal order as one reads through Part I.

“Wit and Wisdom of Charles Watts” is a compilation of quotes from Charles’s letters that were wholly deserving of their own section.

Chapter 16

1869–1870

“Far from the world, O Lord, I flee, from strife and tumult far.”

—William Cowper

Charles may have known he was dying. In his December 1868 letter to Alfred, Charles asked for only one item from Chicago, a “family Christian Almanac.” He probably purchased one each year; they contained information typically associated with almanacs such as weather, national statistics, and so forth, but The Family Christian Almanac was centered on religious stories and themes. What was different this time about Charles’s request was not what he ordered but that he did not submit his usual lengthy wish list.

On January 1, 1869, Charles paid $64.50 for a pair of gravestones. He had ordered them far enough in advance of the purchase date for that cost to include interest. It seems more likely that he knew he was ill and wouldn’t live much longer rather than doing what we refer to today as preneed planning. Charles already had a family plot in the Cyrus Hills Cemetery, which he’d obtained when his infant son died in 1862.

Charles Watts died on March 23, 1869 at the age of fifty-six. We have no details of the cause of death or who was with him in his last hours. The March 25, 1869 Bureau County Republican barely mentioned his passing: “Two deaths occurred near Lamoille last week – old Mr. Norris and Mr. C. Watts – the former about eighty and the latter sixty years of age.”[1]

Thirteen other members of his family and extended family had followed Charles to America: Charles Wiggins and his siblings Thomas and Eliza; Edward Lowe Watts, his wife, Martha, and their children, Edward William and Emma; Frances Sarah Watts Birchenough, her husband, George, and their children, Edward, Emma, John, and Martha (who died in 1866).

The English emigrant and Bureau County prairie pioneer who, together with his “industrious, frugal” wife, Mary Ann, had raised a family on the ninety-acre farm they carved out of virgin prairie and who was responsible for the additional immigration of thirteen others, was gone. Everything Charles Watts had accomplished, all the family members whose lives he had so tremendously impacted, was summed up in one toss-away sentence that had been shared with another poor soul. The Bureau County Republican death notice hadn’t even provided space for Charles’s first name; he was referred to as C. Watts. His age was off by four years. And that was that.

Charles probably died at home. He may have succumbed to a protracted illness, a cardiac arrest, or an accident. Mercedes Bern-Klug notes in her Encyclopedia.com article “Funeral and Memorial Practices” that it was common then for the dead to be prepared at home by surviving family members. If she followed typical practices, Mary Ann, perhaps with her children’s help, washed Charles’s body, dressed him, and combed his hair. Next, the family prepared food and drinks to host Charles’s funeral.[2]

In addition to family friends and Mary Ann’s Baptist minister who would have officiated the funeral, we can imagine who may have been in attendance at the home and possibly joined in the procession to the burial at Cyrus Hills Cemetery: Wife Mary Ann and son Alfred. Daughter Mary Eleanor, her husband Victor Huffman, and their son Alfred Oliver. Daughter Emily and the family’s ward Arthur. Brother Edward Lowe and Martha Watts. Edward Lowe’s son Edward William, his wife Anne Watts, and their children Martha, Thomas, Anna, and Eliza. Edward Lowe’s daughter Frances Sarah had left Australia with her family in 1865 to join her parents in Illinois; Frances Sarah would have been there, along with her husband, George Birchenough, and their children, Edward, Emma, John, and Lettie. Unless they had already moved to Nebraska, Edward Lowe and Martha’s youngest daughter, Emma, her husband, Peter Dutter, and one or both children they had together would have attended.

Another local family that owed its Illinois existence to Charles Watts may not have attended the funeral. Charles Wiggins had married Rhoda Bridges in 1851. By 1869, the couple owned a successful Princeton, Illinois farm and had four children: Mary Alice, Harry, John, and William. Decades after their dispute over the money held for Wiggins by an unenthusiastic Watts, it may be that too much bitterness remained for Wiggins to attend the funeral. On the other hand, the passage of time may have worn away enough of the hard feelings for him to join his extended family in mourning the passing of the man who had led the way.

The landscape surrounding the Cyrus Hills Cemetery has not changed much since 1869. There is still mostly flat farmland as far as the eye can see, and the cemetery is only a mile and a half from what was once the Charles and Mary Ann Watts farm. Driving the route today, it is easy to imagine the bereaved in their wagons on a cold, gray, windy, late-March day, carrying an English-American pioneer to his final resting place.

The Watts family plot is large enough for eight to ten graves. Charles and Mary Ann had intended to eventually lie on either side of their infant son who was buried there in 1862. Six years later, Charles was laid to rest beside his child in a “coffin & box” that cost $19.50. The “box” was his wooden burial vault. His headstone reads:

CHARLES WATTS

DIED

March 23, 1869

AGED

56 yrs. 8 mo.

23 days.

Far from the world O’ Lord I flee

From strife and tumult far.

Charles may have selected the epitaph himself. The words are the first two lines from the William Cowper poem “Retirement.”[3]

Far from the world, O Lord, I flee,

From strife and tumult far.

From scenes where Satan wages still

His most successful war.

The calm retreat, the silent shade,

With prayer and praise agree;

And seem, by Thy sweet bounty made,

For those who follow Thee.

There if Thy Spirit touch the soul,

And grace her mean abode,

Oh, with what peace, and joy, and love,

She communes with her God!

There like the nightingale she pours

Her solitary lays;

Nor asks a witness of her song,

Nor thirsts for human praise.

Author and Guardian of my life,

Sweet source of light Divine,

And, -- all harmonious names in one, --

My Saviour! Thou art mine.

What thanks I owe Thee, and what love,

A boundless, endless store,

Shall echo through the realms above,

When time shall be no more.

Charles was survived by:

Mary Ann Thurston Watts, age forty-nine

Alfred, age twenty-two

Mary Eleanor, age nineteen, married to Victor Huffman and mother of Alfred Oliver

Emily, age fourteen

Arthur, age eight, who was in the care of the Wattses

Mary Ann’s petition for letters of administration listed the following property:

Ten acres of prairie land in Clarion (Township), $500—this would have been the ten adjacent acres Charles bought back from Sally Ballard

Five acres of timberland in LaMoille, $400

Two town lots in Mendota, $600

Stock, grain, hay, farming implements, money, and credits that, together with the above listed land, were valued at approximately $3,500

Charles did not leave a will. The original eighty acres purchased by Mary Ann from the federal government was not listed in estate paperwork, so it must have remained in Mary Ann’s name. The petition identified the following heirs: Mary Ann, Alfred, Mary Eleanor, and Emily. Arthur was not shown in this or any subsequent estate paperwork. He was not a biological or adopted son of Charles and Mary Ann, although at some point he did take their last name.

The probate appraisal listed Charles’s personal and farm property, including four horses and nine cows. Mary Ann was legally recognized as the guardian for her only underage child, Emily B., “minor Heir of Charles Watts deceased.”

Alfred was still in college, and Mary Ann could not keep the place going on her own. Most of the farm equipment and animals were sold off in an August 1869 administrator’s sale. Dozens of receipts were filed with the estate for money and books taken, mostly by Alfred but some by other family members. The town lots, five acres of woodland, and ten acres of farmland were sold at public auction.

Mary Eleanor and Victor Huffman, possibly encouraged by the Olls mentioned in the December 1868 letter, moved with their son, Alfred Oliver, to Missouri sometime in 1869, where they would have another child, Lila May.

Mary Ann, Alfred, and Emily were included in the 1870 First Baptist Church member roll, and Emily was baptized there in April 1870. Alfred was licensed by the church to “preach the gospel of Christ – by unanimous vote.” Church records state, “During this pastorate Brother Alfred Watts was licensed to preach. He has since become an efficient preacher of the gospel.”

Census records show Mary Ann still living at the farm the year after her husband died. Other listed household residents were Emily, ward Arthur, and Mary Ann’s then-widowed mother, Eleanor Thurston.

Chapter 17

1872–1931

“I was talking with a carpenter here today who is from La Moille Ill. who says he used to be a chum of yours in school.”

—W. A. Smith

Emily Watts attended Princeton High, apparently begun as a boarding school, in 1872 and 1873. Receipts for Emily’s tuition and room and board were filed with her father’s estate, which was still open four years after his death. The final document from Charles’s estate was dated June 5, 1873 and titled “Final Report of the Account of Mary A Watts, Guardian of Emily B Watts, Minor Child of Charles Watts deceased.” After Emily’s graduation from high school, her mother took her and Arthur to Holton, Kansas, where Mary Eleanor, Victor, and their children had relocated the previous year.

Mary Ann immediately purchased land in Jackson County, Kansas for three thousand dollars; this may have been intended as farmland for Victor, who would be listed as “farmer” in future census documents. A series of land transactions involving family members would continue there for at least the next seventeen years. By 1875, Mary Ann, Emily, and Arthur were residing with Samuel Stoughton, a farmer, in what may have been an arrangement to provide room and board in exchange for Mary Ann and her children keeping house and helping around the farm.

Mary Ann

Nearly ten years after Charles died, Mary Ann Thurston Watts remarried. On Christmas Day 1878, Mary Ann, then fifty-seven, married widower Jairus Iris Joy, fifty-nine years old, at Mary Ann’s residence. Jairus’s first wife, Rebecca, had died two years earlier.

Mary Ann Watts Joy died on March 18, 1880 at the age of fifty-nine, fourteen months after her remarriage. Jairus buried Mary Ann in the Ontario Cemetery in Jackson County, next to his first wife, Rebecca. Mary Ann’s headstone matched Rebecca’s.

We do not know if Alfred, Mary Eleanor, Emily, and Arthur were happy their mother had remarried. We do not know how they reacted when they saw that their stepfather buried their mother side by side with his first wife and marked both graves with identically designed headstones. We can, however, reasonably guess that Mary Ann’s children conspired to have their stepfather place a specific epitaph on Mary Ann’s headstone, which reads:

MARY ANN

WIFE OF

JAIRUS JOY.

BORN SEPT. 23, 1820,

DIED

MAR. 18, 1880,

AGED

60 Y’RS, 2 M’S, 18 D’S.

Far from the world oh Lord I flee,

From strife and tumult far.

Jairus was not a mathematician. Despite what was carved into her headstone, Mary Ann lived to be fifty-nine years, four months, and twenty-six days old. Mary Ann’s second husband honored his stepchildren’s wish to have a certain epitaph inscribed on her headstone. The words, they must have told him, held enormous significance for their mother.

The children had found a way to reunite their parents in death.

[1] Matson Public Library, Bureau County Republican, March 25, 1869, Matson Public Library, Princeton, Illinois, microfiche.

[2] Mercedes Bern-Klug, “Funeral and Memorial Practices,” Encyclopedia.com, last modified November 6, 2020

[3] William Cowper, “Retirement,” in Poems, by William Cowper, of the Inner Temple, Esq. (London: J. Johnson, 1782)