Separated by 500 years, yet united by their talent, Serafino and Parker embark on similar journeys of discovery while fellow artists, assassins, princes and envious classmates rage and scheme around them.

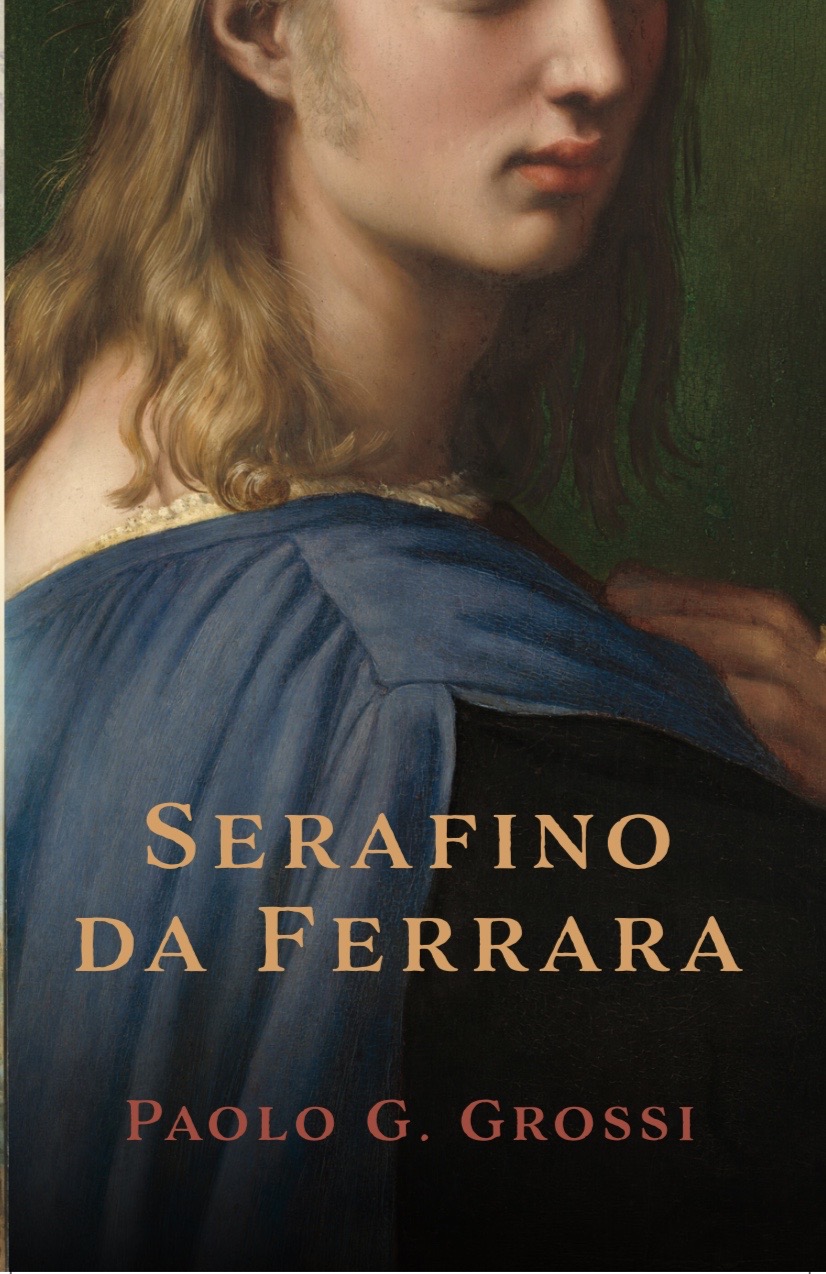

Serafino da Ferrara

Paolo G. Grossi

Also by Paolo. G. Grossi The Tiergarten Tales

Serafino da Ferrara

Published by The Conrad Press in the United Kingdom 2023

Tel: +44(0)1227 472 874

www.theconradpress.com

info@theconradpress.com

ISBN 978-1-915494-29-0

Copyright © Paolo G. Grossi, 2023

The moral right of Paolo G. Grossi to be identified as author of this

work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

Typesetting and Cover Design by:

Charlotte Mouncey, www.bookstyle.co.uk

Images Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington - Bindo Altoviti by Raphael and

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York - Fantastic Landscape by Francesco Guardi.

The Conrad Press logo was designed by Maria Priestley.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

To Silvio G.

Contents

Italian, Italians, and Italics

I. All happy families... 13

II. The boys of Ferrara 35

III. ...are alike 63

IV. Lungo il Canale 91

V. Painting Telegonus 145

VI. Sacellum Sixtinum 193

VII. Rossini Spritz 223

VIII. And then we emerged to see the stars again 249

IX. Book of Revelation 273

X. Santa Maria Novella 291

Author’s Note 323

Acknowledgements 333

Here vigour failed the lofty fantasy:

But now was turning my desire and will,

Even as a wheel that equally is moved,

The Love which moves the sun and the other stars.

Paradiso - Canto XXXIII

II. The boys of Ferrara

‘Go and wake up the signorini, Beatrice, sun is up already.’ She walks up the wooden, creaky stairs and slams open the door of her brothers’ room.

When she pushes the rickety shutters open, the powerful rays of the blazing morningsun flood the walls causing moans and young heads to hide under sweaty pillows.

‘Santa Caterina has already struck six, better hurry if you don’t want father to come up.’

The threat works every morning, though she finds it strange that it has to be repeated. Serafino, Francesco and Cesarino know all too well that the alternative to their

sister’s wake up call is a mild beating by their father. It is actually so mild that sometimes the three boys would rather have fifteen more minutes in bed in exchange for a

good slap.

Francesco and Cesarino run to the bucket of cold water in the next room, diligently prepared by Beatrice; Serafino, the middle one, is allowed to stay behind to wash a bit

more thoroughly. He also has cleaner hose, polished shoes and a threadbare doublet to wear; he is allowed a bit more time to comb his wavy black hair and gather his

books, papers and writing material.

Not an issue with the older and the younger. After the usual reprimand by Beatrice for merely spraying their faces with just water and ignoring the bar of coarse soap on

the small table beside it, they run down the stairs bare chested and barefoot, clumsily tying up their hole-ridden trousers.

They are never reprimanded for that. June is almost at an end and the heat of the plain has risen fast. The chores at the Osteria della Lepre are physically demanding

and they willwear their white shirts only a few minutes before midday,just before the first customers make the beads of the curtain at the open entrance tinkle.

Beatrice has to tidy them up and wash the sweat away from their chests to make them somehow presentable to the clientele. She is used to their grumbles. They are

good-natured boys, hardworking and kind. But not very clean.

The regulars like them and tip them handsomely, their mother apologising to her most distinguished customers that she cannot make them wear shoes to save their lives.

Don Filippo, the most revered notary in the city - notary, in fact, to no one less than Duke Alfonso himself - shrugs and laughs without fail at the complaint, tenderly

ruffling the unkempt hair of Cesarino and furtively shifting a quarter of a ducat into his hand with a wink.

‘Leave them alone, Signora Ippolita, they work hard and it is so hot today.’

The Osteria della Lepre sits on the side of the dusty Strada di Comacchio, a few kilometres from the Porta della Giovecca, the south-eastern gate of the city.

A thriving concern. The city dwellers and the country squires are never put off by the ramshackle exterior of the Osteria. They gladly endure the hard wooden benches

and untiled floor to savour Signora Ippolita’s simple but unrivalled dishes of game and freshly cooked vegetables.

The name is no random one either. Arrosto di Lepre and Lepre alla Birra are her two strong main dishes on the one thin menu. When mother and daughter have been

attending the cauldron all morning, the heavenly aroma from the kitchen window is known to halt riders and carriages on the dusty road and possibly even their horses.

Hardly anyone is able to continue on their journey without dismounting and savouring the earthy lunch.

Rumour has it that from time to time even His Excellency disguises himself as a hunter in order to visit the Osteria and enjoy lunch undisturbed. Apocryphal nonsense, of

course, yet one which attracts even more punters, the locals never tiring of a good gossip about their ruler and his wife. Above all, his wife.

It was witnessed that the Ducal cortege had one day halted by the Osteria. One of the footmen had trudged through the beaded curtain and enquired if the entire place

could be commandeered for a private lunch. A bowing family, quickly recognising the footman’s livery, had of course agreed, unaware of the apoplectic tantrum taking

place in the Duke’s carriage.

‘Me? Setting foot in such a place?’

Her head had swung affronted towards the other side of the road, disdainfully lowering the curtain and lifting her embroidered handkerchief to her offended nose.

‘Lucrezia, everyone at court has eaten here incognito. They are most complimentary. The Lepre alla Birra...’

‘Then you eat here. I am a Borgia.’

Duke Alfonso had raised his eyes to the cloudless sky and signalled the footman to instruct the cortege to set on.

‘And never tire of reminding me.’

Serafino is ready now. Unlike his rumbling brothers, he walks down the stairs with soft gentle steps, his bag across his shoulders, politely greeting his parents.

Francesco and Cesarino, one already on his knees scrubbing the floor, the other carrying heavy parcels of game on his shoulder across the kitchen, affectionately sneer

at him.

‘Il grande testone has arrived.’

They do that almost every morning, but Serafino knows it to be harmless brotherly banter. They are secretly proud of him, the only one in the family studying with Mastro

Filargiro, one of the best regarded - and strictest - tutors in the city.

* * *

It had happened by chance. Like almost everyone - with the exception of the Duchess - Mastro Filargiro had been unable to resist the lure of a lunch or two at the Osteria

and had found Serafino drawing the profiles of the most handsome customers on some papers which had miraculously found the way to him.

He had stood behind him, signalling him not to stop, attentively observing the movements of his hand, the pose of his face, the number of times he had lifted his head to

memorise the contours of his impromptu models.

He had returned the following day with some good quality papers and chalks. To the puzzlement of his parents, he had politely asked their permission to set up a small

stall for Serafino to sit at the optimal distance from the tables. Gently, he had then pointed to a pretty young lady wearing a colourful veil and laid the paper on the table.

He had shown a few corrections to the boy, who had registered and executed them with astonishing speed and accuracy.

Signora Ippolita had then offered a goblet of the best wine of the house to Mastro Filargiro who had spent ten or fifteen minutes carefully perusing the drawing.

Serafino, thirteen at that time, had sat composed and silent at his side, Mastro Filargiro turning his face to him with an approving smile from time to time.

‘Who taught you this?’

‘No one, sir. We can’t afford a tutor. What did I do wrong?’

‘Hard to say.’

He had pulled the drawing nearer to his eyes and placed it back on the table while tightening his lips in thoughtful fashion.

‘And hard to find.’

Serafino had placed his small dirty finger on the drawing.

‘Her jaw.’

‘What about it?’

‘She kept laughing and it kept moving up and down. I had to keep memorising it. I think it’s slightly wonky.’

‘Wonky?’

Serafino nodded, visibly annoyed by his own perceived failure.

‘Why don’t you call your mother and let me have a word with her in private?’

‘Yes, sir.’

* * *

And that marked the end of Serafino’s career as a floor-scrubber and the start of free teaching at Mastro Filargiro’s workshop. Donna Ippolita had remarked that, despite

the good business of the Osteria, they would have struggled to afford the fees - Duke Alfonso’s own nephew was among the pupils - but Mastro Filargiro had informed

her that having Serafino with him was of more value than a bunch of ducats. He would provide lunch and an afternoon merenda to the talented lad.

His wardrobe has also changed. The sons and wards of wealthy Ferrarese families have no use for their out-grown garments and Mastro Filargiro encourages them to

leave silk hose, velvet blouses and bespoke leather loafers behind for the less privileged students. This is approved by their usually aristocratic parents. Despite the

unpleasant hauteur of his consort, Duke Alfonso’s reign is proving a benevolent one and acts of charity have become to be seen as a good way to ingratiating one’s clan

to the ruler.

Serafino slowly transforms into some kind of threadbare young Medici squire, inevitably provoking the mockery of his brothers.

And he is also well liked by Mastro Filargiro’s wealthy young charges. He never hides his lower status and conducts himself with dignified humility, sometimes - to his

tutor’s horror - offering to serve them drinks or refreshments.

Filiberto degli Aldighieri, an older boy with flaxen hair and a larger than life character - and a smaller than life talent - one day finally snaps at Serafino with a roaring

laugh.

‘Messer Serafino. We are all apprentices here. You are not my servant.’

He gives back the cup with a big smile and furtively peeks at Serafino’s drawing on the easel.

‘And I suspect you never will be. Mastro Filargiro, sir!’

‘Yes, Messer Aldighieri, are you about to entertain us with one of your preposterous excuses for doing no work at all?’

Filiberto places his arm around the neck of an embarrassed Serafino and slaps a loud kiss on his cheek. Fino blushes and smiles.

‘Much better than that, Mastro Filargiro. I hereby declare Messer Fino da Ferrara my best friend!’

A roaring applause and a loud stomping of feet on the floor wooden planks follow, pleasing a satisfied Mastro Filargiro who pensively raises his thumb and index finger

to his chin.

‘Fino da Ferrara. That is a good name. A good one indeed.’

The name ‘Serafino’ thus disappears from the school’s vocabulary. Fino becomes worried for Filiberto though and before the end of the day enquires with him about the

wisdom of the new liaison.

‘Are you sure you are allowed to have me as a friend?’

‘Best friend! No, but I will ask my old man. I am the heir, not much is denied to me.’ He winks in conspiracy. ‘If he forbids our friendship, we’ll be wicked and will hide it.’

Aldighieri il Vecchio assents. He has visited the studio and Mastro Filargiro has shown him Fino’s first finished drawing.

‘The origins might be humble, yet the hand has divine inspiration.’

Aldighieri il Vecchio had admired the drawing in awe and looked inquisitively at Filargiro.

‘Have you plans for the lad?’

‘Yes.’

At the start, Fino has to endure a one hour walk to reach the gates of La Giovecca, but his ordeal doesn’t last long. After treading the semi-deserted trail for a few days, a

few farmers and merchants with carts and donkeys start offering him a passage and he becomes so well known that he can actually choose his transport. They all seem

eager to have the honour of carrying the young painter to the city and back. Some even share a bit of bread and prosciutto with him, chatting away, curious about his day

in the company of the real signorini.

A few times he gets carried on the back of a big cart surrounded by a group of very friendly men on horseback. Fino likes them, they are funny and make him laugh.

From time to time they lift the rough blanket covering the cart and give him a jar of olive oil and a hare or a rabbit for his parents.

He never quite understands why they have to drop him outside the gates though. When asked, they say in the most evasive way that they usually reach the city ‘by other

means’.

He asks his now best friend and Filiberto throws a healthy laugh, slapping his hand on his forehead.

‘Oh, Fino, my friend. Poachers and smugglers. Not to worry, they are no assassins, but don’t get caught with them by the Duke’s guards. They won’t know you aren’t

one.’

Filiberto is a natural leader and has formed a mixed-rank gang. Although very conscious of his status, he finds the poor lads more fun and more adventurous in mischief.

Between the occasional brawl and argument the little squad of half a dozen gets on like a house on fire.

Duke Alfonso’s nephew has excluded himself, and, to Filiberto’s annoyance, Fino has kept the habit of bowing at his arrival, something the young man seems to resent.

Around their afternoon merenda, Filiberto, now the de-facto leader, explains.

‘Do not hate him. He’s dying to join us. He cannot. He is a d’Este and also a prince. And his auntie now is a Borgia, god help him. In theory, even I should bow to him but

he doesn’t enjoy the deference. He sits alone while we go out to play and run in the mud. They wanted Filargiro to tutor him at the castle but he refused. He told the

Duke that he thought his nephew was lonely enough as he was. Old Filargiro is not scared of the Duke.’

‘He must be scared of Donna Lucrezia!’, one of the boys laughs out.

‘La “Duchessa” Lucrezia. You’ll have your head chopped off if she hears you!’

That provokes a good deal of laughter, with another boy trying to strangle the offending lad. Filiberto opens his hands in resignation.

‘The d’Este are too big. They are related to princes and kings in the Empire, and England too. He can’t play with us. He can’t tell you this. But I know.’

They have been sitting having their cakes on the floor - an endearing act of rebellion - while Ludovico remains at the table, seated upright, eating his cake in silence.

From time to time Fino sees him looking over and quickly turning his gaze away.

One day, while Fino is intent on working on his first real painting in a separate room, the d’Este boy tentatively walks over and stops behind him, observing the first

outlines of his work. He speaks in a very soft tone, almost afraid.

‘I have seen your drawings. They are rather masterful.’

‘Very kind, Your Highness.’

He huffs and turns his head in mild anger.

‘Please, don’t call me that. And stop bowing to me. It’s ridiculous. I hate it.’

‘But... I can’t...’

‘There is no one here. We are the same age.’

‘I’m scared of getting into trouble, you’re the Duke’s nephew.’

‘You are like the others. You don’t want to be my friend.’

Fino walks closer and notices the boy’s eyes starting to well up.

‘I do. We all do. But... I’m a peasant. You are a prince.’

He takes Fino’s hand in his and squeezes it.

‘I’ll come over for a few minutes every afternoon. Don’t tell anyone.’

‘I won’t.’

Every day the Duke’s nephew tiptoes to the loggia where Mastro Filargiro confines Fino to isolate him from the distracting banter of his fellow pupils. Hardly any of them

is destined for a career in the visual arts and the period spent under his wings is merely viewed by their wealthy families as a rite of passage to refine their sometime

unruly sons.

Every afternoon Ludovico d’Este peruses his secret new friend’s progress with awe, comparing it with his own frankly disastrous rendering of the Nativity.

Fino is for the first time working in oil on canvas. His progress is constantly interrupted by a sneaky stream of nosy boys, in awe at details which they could not master if

they stayed with Mastro Filargiro for a lifetime. The tutor has to start discreetly sending them away, though his fears of them distracting Fino are unfounded.

While having a quick chat - at times even a silly adolescent laugh - the young man carries on with short strokes of his brushes, swapping them over with more suitable

ones, while listening and even joyfully participating in the banter. If anything, upon inspection, the presence of his fellow apprentices seems to inspire a new, more

accurate brushstroke, a tiny correction to the light of the hay in the manger.

Every afternoon Ludovico discreetly holds Fino’s hand in his, nervously checking over his shoulders. When he does that their eyes always meet and stall for a few

minutes, their hearts pumping fast, neither of them reaching any meaningful explanation as to why it keeps happening.

Ludovico is very light-skinned, his eyes bluish-grey, his locks flaxen, the product of stubborn, recurring genes. His grandmother had been a princess hailing from the

northern possessions of the Holy Roman Empire, duly dispatched to Ferrara to marry into the small but ludicrously wealthy House of d’Este.

They stay silent most of the time. The sensation brought about by their hands clasped together is too heavenly to be ruined by words.

One sunny afternoon that changes. Ludovico gently points at the left of the canvas.

‘Your three wise men are very young.’

Fino stares in his friend’s eyes.

‘Are they supposed to be old?’

‘I’m not sure. I think so. And with more garments on.’

Fino lowers his head with a hint of sadness.

‘You don’t like my kings.’

He feels a squeeze of his hand.

‘Of course I do. And Mastro Filargiro?’

Fino smiles, reassured. For some reason he had felt sad at the idea of having disappointed his secret friend.

‘He said the same. But he didn’t ask me to change them.’

‘Caspar looks familiar.’

‘I hope I haven’t offended you.’

‘Nothing you do could in any guise offend me, Messer Fino. How did you manage to draw me without seeing me all day?’

‘When you come over. I look at you. All the time.’

Ludovico smiles, happy.

‘I look at you too. Some nights you are in my dreams.’

Ludovico looks over his shoulders and through each of the doors leading out of the loggia. Almost sure of their complete solitude he moves forward and kisses Fino on

the cheek, their hands melting in one another. They briefly smile at each other and the Duke’s nephew leaves.

When Fino reaches his fifteenth birthday Mastro Filargiro orders his housekeeper, Donna Elvira, to serve torte alla crema and half a goblet of the best vino rosso diluted

with water, the one in the barrel sent by Filiberto’s father as a gift of appreciation for keeping his unruly cub out of trouble.

The boys adore Donna Elvira. In her early fifties, unmarried and with no children of her own, she has an oversupply of motherly affection and not afraid to bestow it on

the young men with cakes, sweet drinks, hugs and ruffling of wispy hair.

She also arranges all the donations of clothing and shoes, knowing the boys who need them more urgently than others, remembering their sizes and even their tastes.

She seems to be more affectionate with the sons of wealthy or aristocratic families. This is planned. She is acutely aware of the demands on them. Their mothers are

probably similar to the Duchess and she regularly finds some of them in secluded corners of the house, hiding their sobbing. The poorer lads seem happier and less

tortured in their destitution.

After the celebrations, everyone is swiftly ordered back to work. As he does every afternoon Ludovico appears behind Fino though this time he doesn’t take his hand. He

has a small blue leather box in his hand and holds his arm out in an offering pose.

‘For you.’

Fino’s brown eyes open wide, jolting Ludovico’s heart to near explosion.

‘For me?’

‘Happy birthday.’

Almost shaking, Fino takes the box and slowly opens it. He holds the thin gold chain with a little square pendant in his hand, his jaw stuck open.

‘I... I can’t accept this, Ludovico.’

‘I haven’t stolen it. It is mine. I have a few. It has the image of San Contardo, the patron of our House. Our coat of arms is on the back.’

‘It’s beautiful. People will think I have stolen it. It’s too much.’

‘Hide it under your shirt. We shall be the only ones to know about this. I don’t want you to ever take that off. It will remind you of me when far away.’

Life throws unforgettable moments at us. When we can no longer control the boiling cauldron of emotions that has been brewing over a fire of repressed feelings.

Ludovico performs his usual check and after some fretting hesitation meets Fino’s lips with a spasmodic, almost unhinged thrust.

Fino slowly opens his mouth, their tongues merging, something in their chests close to a conflagration.

Ludovico takes his hand, leading him away.

‘Come.’

He follows him down the staircase on the side, towards the back of the house, facing the ramparts of the walls. A small stream runs behind the house and this is where

the apprentices go to discard used jars of paints into the river. It is very secluded though not entirely safe as any of the boys can arrive to perform such tasks at any

moment.

When there, Ludovico gently pins Fino to the wall and the kissing become frenetic, unstoppable. Then their hands find their way into each other’s hose and, as always

happens on the first-ever fondling, they find themselves in the midst of a cataclysmic flood after only a few seconds.

Heavily breathing, Fino lets his head fall on the shoulder of his secret friend, kissing his neck, oblivious to the almighty mess on their hands, some of it washing away in

the stream. Ludovico’s hand is caressing his hair, panting.

‘I think of you all the time, Fino. I can’t even eat anymore. I don’t understand what is happening to me.’

‘I don’t know either. All I know is that it is happening to me too.’

Ludovico slowly detaches himself and they haphazardly wash themselves up in the stream.

‘We’d better get back. Someone might come.’

They hold their hands together until the top of the staircase, then Ludovico turns to Fino.

‘I know we won’t be together forever. You will be sent away, to some important artist’s workshop. And I am at court. It’s like a prison but that will be it. A choice will not

be given to us. That is why I have given you the pendant. San Contardo will protect you and it will remind you of me. Don’t forget me, Messer Fino.’