CHAPTER ONE

“To understand the history of our realm of Seramight, we must first understand the nature of the world we live in. Three realms of life circle each other in the dark Abyss, bound together by the Great Web. The celestial realm is ruled by the gods, the ethereal by the tsaren. Our own earthly sphere was ruled by the Kings of the Sacred Crowns for three thousand years, before Tsarin Reval destroyed their illustrious houses in the Sundering War.”

History of Men, Gods and Magic,

By Priest Oderrin

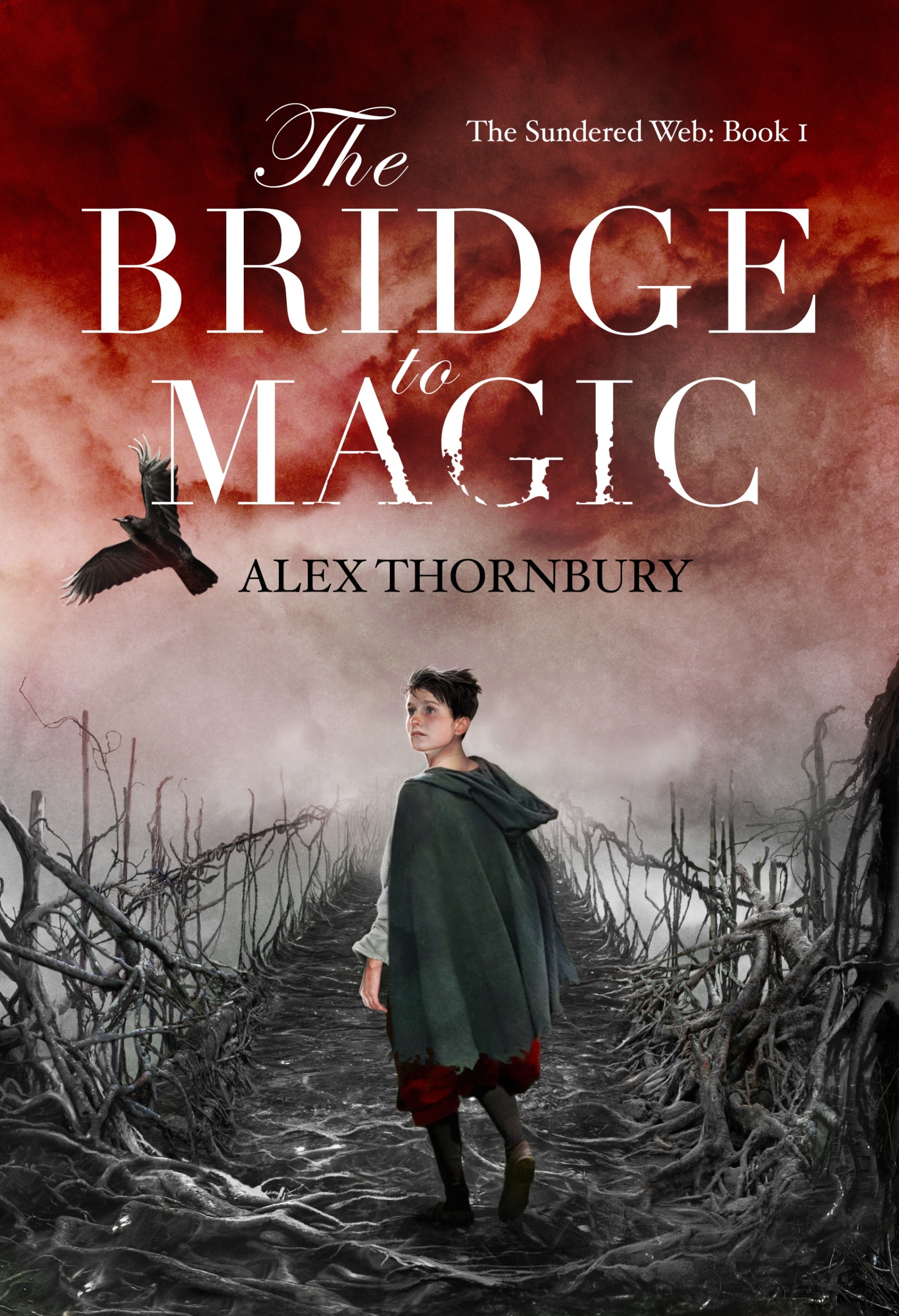

All stories began and ended at the Bridge to Magic.

So it has been for six hundred years—the story of this age, the story of the battle against magic and its banishment after the Sundering War. And Elika’s story, too, began with the bridge. Were you to ask any man, woman or child, they would say their earliest memory was the first time they beheld its dark path or heard whispered tales of it in their cots.

There was a time before the bridge was forged, but those stories had been mostly forgotten. The dark history of that bygone age was now buried in the archives of the priests. Only the echoes of it remained on the tongues of minstrels and drunks. Elika had heard them all and each tale seemed more terrible and unimaginable than the other.

Those were dismal times of endless wars—men against magic, magic against men. The time when even the storms and rains were at the mercy of magic and its fickle moods. It might snow in the summer, or the hot winds might carry sand upon them, burying entire cities. Honest travelers feared to ride through the forest, lest the trees attacked them. A farmer might wake up to find his river flowing the wrong way or dried up altogether. Those days were gone and might have been forgotten, but for this stark reminder before Elika’s eyes.

And who had not stood before the dark bridge in their last moments, facing that choice they all must one day make?

Like that hoary, old codger in the ale-stained uniform of the city’s Blue Guard who had stood before the bridge for nigh on an hour; unsteady on his legs, his sour breath steaming in the crisp, winter night, drinking deeply of the cheap gin, which was as likely to kill him by morning as what he now faced. He took a long swig out of his bottle as he braced himself for the unknown fate ahead.

Elika sat huddled in the doorway of an abandoned house, watching him, needing to know whether he would reach the other side or die crossing. Her ears filled with the howling winds rising from the great chasm, and she did not need to imagine what he was thinking, staring as he did at the monstrous bridge and the lifeless bank beyond, for she was thinking the same—surely it is better than what remains at our back. Better than what approaches.

She clutched the cloak tighter around herself against the biting gust of wind trying to rip it from her. She had scavenged the woolen cloak some days ago from a dead beggar, and it still smelled of his mustiness. She pulled up her knees to her chest and clamped her icy hands under her arms. The stone wall was cold at her back. Her breath steamed. She waited and watched the old guard take another wobbly step toward the bridge, seeking courage in his gin-dulled mind.

He took another gulp, stared at the empty bottle in surprise, then threw it aside with a foul curse. The bottle hit the frozen ground and rolled off the edge of their world into the chasm, to fall for eternity in that endless darkness.

It had been a long and depressing day, and Elika was almost glad the old guard was finally here. Only that day everything had changed. Only that day they had learned that Terren, their city, now stood alone in the relentless advance of the Blight.

That day, as the sun was rising, Elika was there, high above the gathered crowds, watching from the rooftops as the Blue Guard rode through the city gates, whilst melancholy bells announced their return. This old guard was amongst the rag-tag force who had left not twenty days ago to scout the boundary of the remaining lands still untouched by the Blight. Sent out by the king, they had set out to discover the fate of the only other remaining city, to find out why the trade caravans from Drasdark had not arrived that summer whilst those that left Terren had not returned. Now, the Blue Guard had finally come home.

They rode silently, their faces haunted, the desolation in their eyes as stark as the lands beyond the bridge. The same desolate silence had engulfed the crowd, and the slow clip-clopping of hoofs on the street sounded loud and final.

Behind the returning guards walked a long line of stony-faced, bleak survivors of Drasdark, carrying the barest of their possessions in fur bundles. There would be no more trade caravans. Terren was now the last refuge of man. Magic had won after all. And soon, like everyone else, Elika too would have to face the impossible choice, the only one left to them now; fall to the Blight or face the Bridge to Magic.

With the shadow of that choice looming high overhead, it was easy to fall into despair, and it had taken great effort to push it aside and remember her daily task. That choice was still too far away, she had told herself, whilst her stomach was hungry now. Besides, there was still time. The king and his priests would find a way to stop the Blight. All they needed to do was purge every echo of magic left in their world that drove the punishing Blight. She had clung to that hope even as she watched the drawn faces of the guards who had lost theirs.

It was said those who had faced the Blight often returned to face the bridge. Often enough it was true, and an orphan like her did not reach the age of fifteen years without learning how to see the signs of men on the edge. And she was better than most at reading men, at seeing those who fought to hang on to the shreds of their decaying hope. It was barren hope, nothing more, which led them to believe that perhaps whatever lay on the other side of the bridge, death or some manner of uncertain existence, was better than the Blight. All you had to do then, when you saw those death-walkers, was stalk them and wait.

So when the Blue Guard had ridden through the city gate, her gaze had instantly settled on this old picket with a frost-nipped nose. She could read men and instantly knew he would face the bridge that day. It was not in his eyes, as Bad Penny had taught the young ones in their pack—his gaze was dull, uninterested like the rest of them—but in the set of his lips. They were pressed together in a determined way, stubborn almost. Elika could almost hear his thoughts—thinking any more about it won’t change me mind. I’ve seen enough. I know what it is that approaches, and I know what it is I must do. It’s the bridge for me.

She had been the first to mark him. It was why Bad Penny always sent her out as a spotter before anyone else. She did her part and signaled one of the younger kids milling about on Tollgate Corner to run and tell Penny that she had sighted the target to follow. Penny would send the scouts to learn what they could about the death-walker. And when they found his home, they would send for the looters. Until then, she had to keep him in her sights.

So she had followed him in the shadows all day, whilst he stumbled from tavern to tavern, chasing that evasive courage in the bottom of his tankard. It was his last day of life in this world, after all, and a man had a right to drink himself to oblivion if it pleased him. Except, there was not enough gin in the city to douse him in the courage needed to cross the bridge. That always came from within. She had seen many a staggering drunk turn away from the bridge, and many a sober man take that fateful step onto it. And she was certain this one had enough stubbornness to take it. His mind, as he was no doubt telling himself, was made up.

As he drank his last coin, he told any near enough to listen of all that befell the Blue Guard on their way to the new border of the Blight, and all they had seen since they came upon it. She’d heard enough such stories to pay them little mind. They were always the same. Aye, it was creeping toward them, and all it touched slowly died and turned to dust. And aye, only Terren was now left in its path. You did not dwell on it, else the temptation of the bridge or the eternal chasm it spanned might sink their tendrils into you. If she listened too closely, she might just start thinking of things other than getting enough food to live through the winter.

Still, as the day waned, her mood grew more and more dour. She had learned more about the guard than she wanted to know. Learned of his wife’s death from the sweating fever, and his son who took the bridge after he had lost the use of his arm in a bar fight and could no longer earn his keep, of his daughter who was heavy with another child she did not want. He suffered pain in his knee from an old wound that plagued him more and more each passing winter. He hated the darker ales, for they turned his stomach at the end of the night … Elika did not want to know any of it, did not want to become bound to him. But she had listened and came to like the old codger and now she would not rest until she knew his fate.

So here she was, sitting, waiting in the swirling snow flurry, long past when she should have returned to the safety and warmth of her den. He took another staggered step forward, past the black, grasping roots which anchored the bridge to this world. They sank into the cobbles of the old street like talons, glowing like slick skin in the flickering oil lamp across the street. It was the only light in the whole of Rift Street alongside the edge of their world.

The old guard stood there for another long, undecided moment, then cursed on a steaming breath and took another step toward his uncertain end. Again, he halted. Only the blood-salt barrier, a thick red line in the melting snow, lay between him and the magic of the bridge. Salt soaked in blood was the only defense against magic. It was how men long ago defeated it in the terrible war that sent the mighty tsaren fleeing.

Elika took a deep breath and hoped he would be spared the fate of reaching the other side. She had watched many a wretched soul face the bridge and thus knew the first step onto it was the most important. Once taken, another would follow, and then another, each one less labored, more determined, and then resolute. One step after another coming quicker, until they reached the point of no return …

Once, she might have tried to stop him. Just as once she had tried to stop a noblewoman with a babe in her arms from doing the same.

“Lady, there is hope,” Elika had told her urgently. “They say the king has found a way to halt the Blight. He sent the priests out toward it …”

The woman had turned her empty gaze to Elika, handed her the babe and without a word strode out onto the bridge, and perished before reaching the end. Elika had been only six then, but as she was the one to bring the babe to their Hide, it was up to her to look after it. Those were the laws of their pack. She tried, but the babe cried and cried and refused to eat the stew, taking only bread soaked in water. There was no milk to be had unless you were gentry, and the babe died soon after in her arms.

No one tried to comfort Elika. She should have known better than to torment the poor babe for pity’s sake. It would have been kinder for her to perish on the bridge in the embrace of her mother.

It was a hard, bitter lesson, and Elika had learned it well. After that, she never stopped mothers with babes, never picked one up from the frozen streets where they were left to face a quick, merciful death. She had learned to shield her heart from the endless river of misery and hunger that flowed through the streets of Terren. Aye, it had diminished her, made her less somehow, but it had kept her alive where she had watched others perish.

Since then, she only watched the desperate take the bridge from afar.

Bad Penny was right; there was nothing you could say to change their minds. Their hearts no longer lived in this forsaken world.

Elika caught a flash of movement in the shadows between the buildings. It was inevitable the others would sniff out the old death-walker before the day was done. One-eyed Rory of Peter Pockets’ gang emerged to lean on the corner. He was, as ever, impeccably dressed in a silk shirt and silver vest, with black kid gloves and a long fur coat. You’d never mistake him for the gentry, however. He did not carry himself as one, did not talk like one either. He was as much a thief as any of them, and despite his plush, stolen clothes, just as desperate. She paid him no mind.

Rory nodded to her, a wicked glint in his remaining dark eye. “Still here, is he?”

Elika continued to ignore him.

Unlike the others of her pack, she did not bother to hide. Little Mite would be angry with her, but why bother hiding from the other watchers? They all knew each of them was there. Farther away, she had already spied the other looters, waiting for the signal to the race to claim the old man’s remaining earthly possessions—waiting, like greedy vultures, for death. And she was one of them.

If she could, she would have found another way to be. But there was no other way. She had not only herself but the pack to look after. If it meant robbing the dead, then she’d do it. As one of the oldest in their pack, the weight of responsibility for the young ones rested with her as much as with Penny and Mite.

Today, luck was on her side. The old guard was one of those few who took nothing with them across the bridge, except the clothes on their back and their wits—not even the hope of reaching the other side. He left everything behind: food, grain and flour, coal lumps, blankets, clothes and shoes … everything their pack desperately needed.

Unfortunately, he was also a city guard and thus one of Captain Daiger’s men. Likely, they would have already gone through his home, laying claim to and hoarding the best pickings. They would not have taken anything, though. No, not yet. Not until the old man was dead or on the other side. Else claiming his possessions was thievery. And the king hated thieves more than murderers. Looting, however, was tolerated. After all, those who took the bridge never returned. Captain Daiger’s men were likely guarding the doors until they received word the old picket was gone and not coming back.

“Bloody hell! Looks like he’s about to change his mind,” Rory said to no one in particular.

“He won’t,” she said.

“Confident, are ye? Why are you here, anyway, Spit? You won’t be getting his loot. My men are already outside his home, and they’ll cut any ragamuffin who tries to sneak past us.”

She hated being called Spit. It was the name they gave the orphans. “Name’s Eli,” she mumbled, though why she bothered she did not know.

Rory knew her name, knew all their names, for it was his job to know. He was the one Peter Pockets sent out to catch and bring in those young ’uns who might be worth something to Pockets’ gang. He was also the one who delivered the less savory messages to competing gangs when they strayed from their own hunting ground.

“Sure it is, Spit.” He gave her a mean, toothy grin. His yellowing teeth were large in his long, gaunt face, and made her think of a fox’s snout. “Why don’t ye just go back to your mouse hole and save yourself being cut again?”

“Not here for his loot,” she lied and instinctively scanned the buildings for Little Mite, in case Rory was of a mind to cut her now and be done with it.

Mite was also watching, though she’d never see him unless he wanted to be seen. Mite only needed to give the signal across the roofs for Tick to slide down the chimney into the old guard’s home before Captain Daiger’s men got their own signal. Tick was fast and wily. He’d be quick to grab what he could and be gone before anyone had the mind to chase him. She’d already seen his pleased face from afar when he had signaled to Mite that he was in position. There was good looting to be had with this one.

“So, here for the spectacle, then?” Rory smirked. “Always thought you were morbid like that, watching them with those large, icy eyes of yours, as if you were death itself urging them on.” He shuddered. “Evil pup. Maybe you be thinking of taking the crossing yourself, hey Spit? Like your ma and pa.”