“Our life is no dream, but it should and will perhaps become one.”

Novalis

Iquitos, Peru

September 8th 1926

The doors of Cavendish House opened just after dawn, as the mournful call of the Common Potoo drifted through the mist. Lamps flared behind the shuttered windows, dimmed a little as they were adjusted, and began floating through the rooms of the big house under unseen hands. The sizzle of bacon on a skillet and the smell of coffee, murmured instructions growing louder. As the sun cleared the treetops, it was as though Pachamama herself was drawing the mist back into the jungle with a slow intake of breath.

A steady stream of tea chests and rough wooden crates were brought out and deposited on the gravel drive. Horse-drawn carts began to arrive from Iquitos Town. They queued beneath the giant trees, waiting to be loaded. The men got down, watered their horses and stood beside them smoking cigarettes in the warm, green shadows.

Alice Cavendish watched it all from the bottom of the long, sloping garden. For an hour she had been slumped over an iron table, chin resting on her folded arms, eyes following the labourers and servants as they went back and forth through the entrance to her home. Occasionally, she would hear a shrill cry from her mother upstairs, demanding something be done more quickly, more carefully, and yet the labourers seemed indifferent to her demands. They moved with a languor befitting the rising temperature.

The previous Christmas, Alice’s father had brought back a steel toy from England. It was a Noah’s Ark, almost as big as Alice herself. When the handle was wound, Noah, his family and the pairs of animals would clank along on a chain system,

1

enter the bow of the ship, then reappear at the other end and go around again. At regular intervals, a tiger and a whale would pop up at the tiny windows.

Alice’s house reminded her of that toy now; somebody, God maybe, was turning a handle very fast and had been all morning.

Despite what her parents had told her, Alice had never believed any of this would actually happen.

She got to her feet and stretched her arms. The sun was almost above them now and her layered dress was soaking up the heat. As she wiped her brow and looked around the garden, she saw the butterfly net lying beside the long rows of her mother’s prize orchids. Alice walked over and picked up the net. She moved with quiet deliberation along the perfectly tended border, trailing the net through the flower heads then slashing at them with vicious snaps of her arm. Large, torn petals fell around her like discarded handkerchiefs. The vandalism improved Alice’s mood for only a few moments. She turned her attention to her nurse, Lizzie, who was watching the Indian men haul crates onto the horse-drawn carts. Alice crept up and gave the young black woman a whack on the elbow with the handle of the net. Lizzie spun around, a mixture of pain and shock on her face.

Alice smiled. “You are paid to attend to me, Lizzie, not lust after men – Peruvian men at that.”

Lizzie glanced back at the house. Mr Cavendish was watching from the study window, his whiskery jowls wreathed in pipe smoke. “I was not … Where did you learn that word anyhow, child?”

Alice slumped to the dusty lawn, which had been left unwatered since the decision to move had been announced. She sighed, began tapping the ground beside her with the net, and then tossed it aside.

2

“I know lots of words …” She lifted her chin and gave Lizzie a contemptuous look, which quickly crumbled. Her eyes filled with water. “It’s not fair!”

Lizzie knelt and took her hand. “Life ain’t supposed to be fair. But your new home in Malaya, well, it will be just as fine as this one … finer I heard.” She stroked the back of Alice’s hand for a few seconds, and then stood up. “Come along; get up from there now or the ants will have your buttocks for lunch.” She smiled in encouragement. It was customary at this point, for Alice to mock the way Lizzie pronounced the word ‘buttocks’, with so much emphasis on the second syllable.

Alice got to her feet slowly. Tears continued to pulse down her cheeks, but now there was a thoughtful look on her face, as if she was wrestling with something. “I’m accustomed to far greater invasions. Father … he …”

From the house there came the crack of a whip and the slow crunch of displaced gravel as another load headed for the docks. Lizzie took the girl’s arm and turned her away from the house. “You mind your tongue now, and be careful where you wag it.” But her tone melted quickly, and she put her arm around Alice, pulled the girl’s head into her stomach and stroked it. “He comes to me at night.” Alice said. She began sobbing into Lizzie’s apron.

Lizzie looked back at the house in alarm, fearful the words had carried somehow. Her own eyes began to fill. “Oh Jesus, that’s why he tired of me,” she whispered. “I am so sorry honey, but he has rights over you and me, all of us here. It’s a burden we have to carry, only God knows for why.”

Alice gripped Lizzie’s waist tighter still. “And now I have to travel halfway across the world with him!”

“Oh my Lord,” whispered Lizzie, looking over Alice’s shoulder. “Would you look at that?”

Alice, startled by the change in Lizzie’s voice, turned to see

3

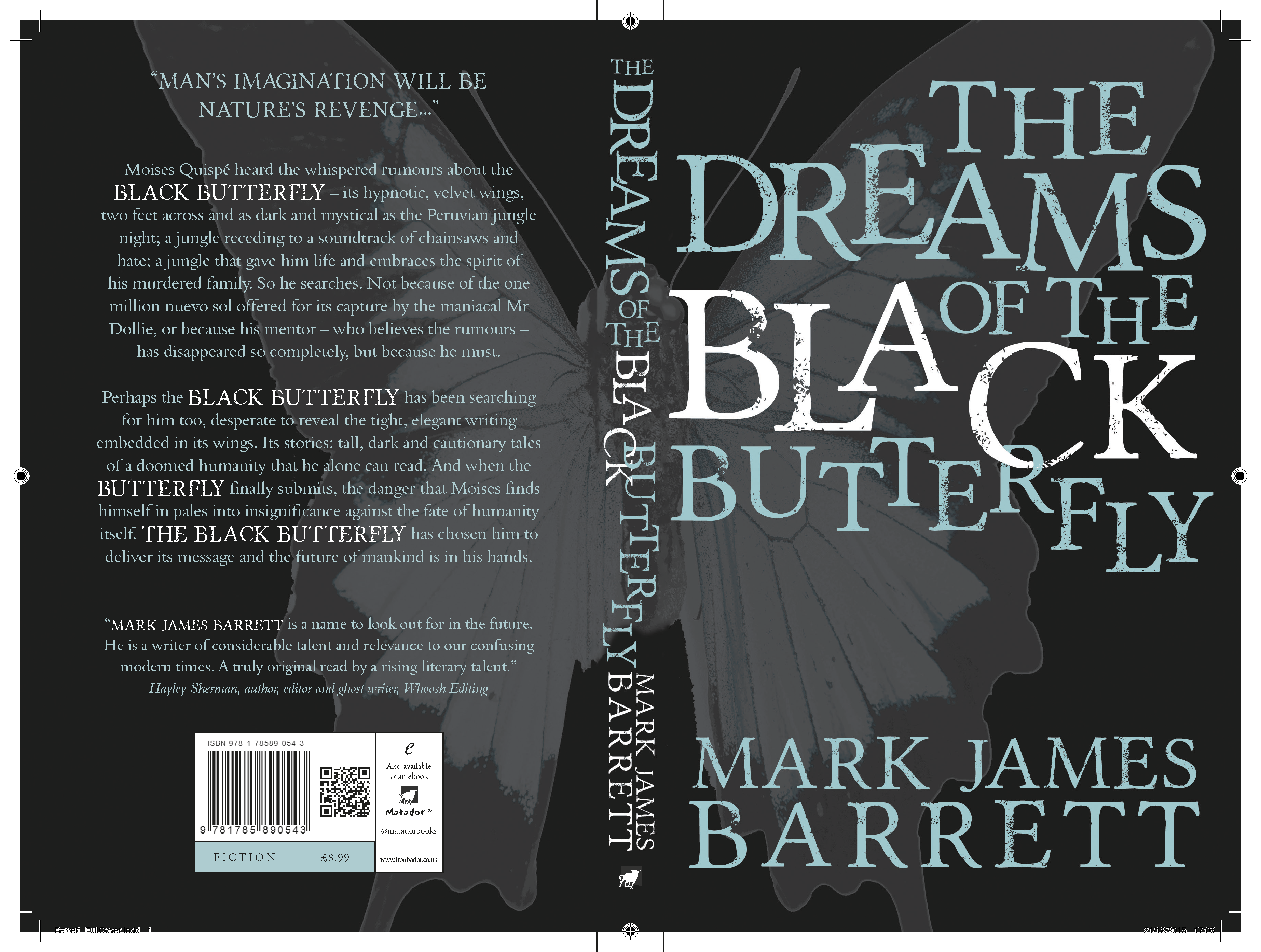

what had caused it. Sitting not 10 feet from them was the biggest, blackest butterfly she had ever seen. It was resting on the pacay tree at the very end of the garden, balancing on the tip of a giant palm at head height. Alice got the impression that the creature had just alighted there as she turned, because the palm branch was swaying slightly in the still air. The butterfly opened and closed its wings slowly and they flashed with a rich darkness. “Goodness, it’s enormous!” Alice wiped her eyes and walked towards it. She reached up to the creature and tentatively pushed her fingers under its head, hoping it might sit on her hand. The black butterfly’s furled proboscis twitched and Alice noticed the glossy hairs around its bulbous eyes. The wings opened for a moment and then closed, each of them as big as the fan her mother cooled herself with when she sat in the parlour each evening after dinner.

Lizzie joined her. “Be careful there, honey.”

“It tickles,” Alice said, a shiver running over her sweating skin. She giggled as the creature edged onto her hand and settled there.

“Where did you come from?” She asked, as if she were petting a puppy.

Alice felt a sharp jab in her palm, and whipped her hand away. “Ow!” She cried, stumbling backwards, shaking her arm in shock. A light-headedness overtook her quite suddenly. The butterfly’s wings opened again, stretching wider and higher until everything else seemed to be blotted out. Alice felt like she was falling into them …

Vaguely, she heard Lizzie calling up to the house for help and people shouting her name. There was a blur of movement as one of the gardeners passed her with a machete and cleaved the butterfly almost in two, across the wings and through the abdomen. It fell to the floor with the palm branch beneath it and lay twitching feebly at Alice’s feet. Her father caught her in

4

his arms.

“Alice! Alice! What happened?” he asked breathlessly. The thick smell of tobacco filled her nostrils and she wished the butterfly had taken her away.

“It bit me, Father. I think it bit me.” Alice held out her hand to show him the puncture mark on her palm. As he took hold of it, she looked up and saw eyes watching her from the trees just beyond the end of the garden. They were human eyes and just as quickly as she had registered them, they were gone.

* * *

5

I eventually found the Quechua Indian who had started all these rumours about three days down the Rio Maranon, in a tiny village that had probably never had a name. My guide, an indolent Mestizo I’d procured in Iquitos, located the individual after much prevarication by the locals.

I can assure you, I am not a man for melodrama, but there was a terrible atmosphere in that little hut; the smell was ungodly, the air a soup of mosquitoes. I caught but a glimpse of the butterfly in question, laid out on a rough, wooden table in the corner. The Yagua Indians, four of them, shuffled around it as we entered. The insect was large, easily two feet across the wings, and black as a jungle night.

He was slumped against the wall, a tiny man whose eyes looked neither at us nor past us, but seemed to be turned in upon himself, watching perhaps, as his mind slid slowly off the edge of the known world. My guide tried to get him to speak for nigh on an hour and I had just about given up on the whole enterprise. I remember saying, “The fellow’s beef-witted; we will get nothing from him,” but it was clearly worse than that.

Then, quite without warning, he began talking.

“Well?” I asked my guide when he had dried up. “He says that he took the black butterfly from the forest, near this place, that it bit him.”

“Bit him? Preposterous! What else, man?”

“He says only that there are stories in the wings.”

I tried to get more of course, but we were ejected soon after and there was nothing for it but to head back to Iquitos. I don’t think I shall ever forget the man’s eyes, and those words he kept repeating.

“Hay historias en las alas.” There are stories in the wings.

Extract taken from Following the Amazon, William Musgrove, 1834

6

The Pacaya Samiria National Reserve, Peru

October 2nd 2006

An unearthly roaring rolled through the treetops of the Pacaya Samiria National Reserve, waking Moises Quispé from a shallow, fitful sleep. He pulled back the mosquito net and lay shivering for a few minutes, listening to the branches high above him rattle violently as troops of howler monkeys disputed territorial rights. Large, dew-wet leaves sailed down from the frenzy and slapped against the roof of his tambo. Moises pulled the thin pillow around his head and began humming into it, hoping to drift back into sleep, knowing it was futile.

He gave up after a few minutes and swung himself out of the hammock, grunting like an octogenarian who begrudges struggling through one more day of life. Half asleep, he moved across to his lookout chair, noticed a vicious looking bullet ant had found its way in and crushed it beneath his boot. His blank eyes reflected the mist as he sat back and pulled the blanket from the hammock to cover his legs.

The discordant opera echoing through the forest grew steadily louder as the mist dissipated. Moises knew dawn’s arrangement by heart; it was the soundtrack to his life. Sometimes he wished for a moment of peace and felt guilty for the wishing. The rituals he was listening to had been practiced unbroken for millions of years, so why should they pause for him? The eight years he had spent adding his own communion had seemed much longer: reciting the same prayers every morning and repeating the same movements. In the steaming darkness outside the tambo, those creatures he honoured had always seemed oblivious to his ministrations.

Moises stretched his arms with a sigh and took a gulp of

7

water and a handful of grubs from his backpack. Occasionally he raised his binoculars in response to movement outside the hut, the flutter of a parrot’s wings perhaps or a peccary rooting around for its breakfast on the gloomy forest floor.

His mind, starved of new experience, circled around the same old subjects, like a condor returning to bleached bones in hope: Hawthorne … the black butterfly … and Señor Dollie of course. Moises turned the improbable figure over in his mind again: one million Nuevo Sol to anyone who captured the elusive black butterfly. But the chances were so small. He had been moving from one tambo to another for half of his life and had not even caught a glimpse of the creature. The little hut in which he sat was tambo number six; every one of them looked the same, felt the same, and la selva was vast. It was his love of la selva that sustained him, but his heart felt as black as he imagined those wings to be. He had to find the butterfly before anyone else did; yet he was so tired of looking that a growing part of him wished someone else would find it, just to release him from the dream of success.

His tutor Hawthorne had told him a secret the previous year in Iquitos: something Moises might not have believed had Hawthorne not disappeared soon after, vanishing like people sometimes did here – completely and without question or comment. The secret had sustained him so far, but with each empty day that passed, he began to doubt the truth of it.

By ten o’clock, the jungle had quietened and he felt himself drifting again, lulled by the heat and the monotonous purring of the cicada. Through his fluttering eyelids he registered movement far above him. Something large and dark was floating down from the canopy in a graceful spiral.

Moises stood up.

Beside the slow, obsidian swirl of the river were a number of puddle clubs: groups of butterflies sitting with their wings

8

folded, like clusters of miniature yachts littering a muddy shore at low tide. They gathered there every morning to suck the minerals and salts from the moist soil. A black shape had settled among them.

Moises leaned forward to part the netting, brought his binoculars up and fumbled to adjust them.

“I see you,” he whispered, and flakes of dried mud fell from his cheeks as he smiled.

The sounds of the rainforest receded. A cold pulse of sweat broke on the boy’s skin and his belly began to crawl; the ghosts of the catfish he had eaten the previous evening circling inside him. Was it true? Finally confronted with the creature, he realised that he had never truly believed in its existence before this moment. To his weary eyes it appeared more solid, more real than everything around it, and yet so black it might have been a hole in the jungle, a fluctuating glimpse into another world.

“Exquisita,” Moises murmured. He ducked through the mosquito net in a fluid movement, his eyes never leaving the quarry as he gently teased the telescopic net from his back sling and began to extend it.

The black butterfly was less than fifty feet from his hide. Moises halved that distance in a matter of seconds, treading softly between the groups of twitching butterflies, his breath coming fast and shallow. A few of the insects rose into jittery flight and he paused. The black butterfly was completely still, detached from it all, like a rare god fallen to earth. Moises moved his feet again, much more slowly now, but the disturbance spread. Soon delicate clasps of colour were flickering all around him. He noted a few of the species whose names had been drummed into him these past few years: the clear wings of Greta oto, flashes of rich orange from a Dryas iulia drifting into sunlight, blood red and sky blue from members of the Nymphalidae family, and the yellow, leaf-like Pieridae.

9

Moises was within 10 feet when the black butterfly finally reacted to all the commotion. It opened its velvet wings and slowly lifted from the ground. He broke into a run, instinctively swinging the net in a great arc to overtake the creature as it rose towards the safety of the canopy.

“Pachamama! I have it!” Moises cried in disbelief, as he pulled the net towards him and fell to the ground, holding it down so the butterfly could not escape. He unscrewed the long pole and tossed it into the undergrowth. “I have it!” he repeated. It was unbelievable. He looked around as if to find someone to verify what had just happened. He shook his head, laughed a little, felt a scream rising in his throat. The insect began to flap so he held the net a little tighter, cooing as if he were tending to a fussing infant. Moises pulled out the other half of the capture net from his shoulder bag and slid it under the open end of the net between ground and butterfly. He snapped the catches on the frame and sat back. Tension left him in a shaky sigh.

Behind him, the other butterflies settled back to the mud and the noises of la selva seemed to resume the usual pattern in his ears. The giant insect in his net had folded its wings and was still, as if finally accepting its capture. Moises pulled at the net to give the creature some room to move inside. He stared absently into the trees for a moment and shook his head. What he had done was sacrilege. What he intended to do was even worse. There was a prepared syringe in his bag. He gripped the butterfly’s wings gently between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand, and with his right, pushed the syringe through the net towards the creature’s abdomen. His thumb hovered behind the depressor. Moises had never considered this moment in any detail before now, maybe because he hadn’t really believed it would come to pass. Now, he realised that his heart didn’t seem strong enough for such a crime against Mama Selva, even if it might be for the good of the jungle in the long run.

10

With a grunt he willed himself to push down his thumb. He was paralysed. He just couldn’t. He needed more time to think.

As he was removing the syringe from the net, his head filled with a mixture of relief and failure, a huge, hollow crack resounded through the forest behind him. He dropped the net and turned just in time to see a 60-foot barrigona tree cut his tambo in half. The walls opened like a V and collapsed as the splintered roof beams spun away in all directions. A cloud of bark dust and dry leaves rose from the impact and hung in the air for a few moments. From beneath the wreckage there was the feeble cry of something trapped and dying and then a relative quiet descended upon the area. A spider monkey came out of the mess, moving along the fallen trunk cautiously. It gave Moises a quick glance, skipped onto a nearby tree and ran back up to the canopy.

Moises stared at the destruction. If it had fallen ten minutes earlier, he would have been under there, a banquet for the ants. What did it mean? He lowered his head and closed his eyes, muttered a brief prayer. When he opened them again he turned quickly, picked up the net and gripped the butterfly as he had before. Before his nerve faltered, he pierced the insect’s thorax and emptied the ethyl acetate solution into it. The butterfly flapped frantically in response and Moises felt a sting in his hand; he had been scratched by the net or the insect somehow. He sat down on a tree root and sucked at the nick in his thumb.

The insect became still.

“Lo siento mi hermano,” Moises whispered and his mudcaked face soaked up the tears like a dry riverbed.

On the journey back to the boat, his thoughts were consumed with one thing: examining the butterfly to check it was as special as Hawthorne had heard. But the microscope was far away.