First 3000 words Chapter 1

The arrival

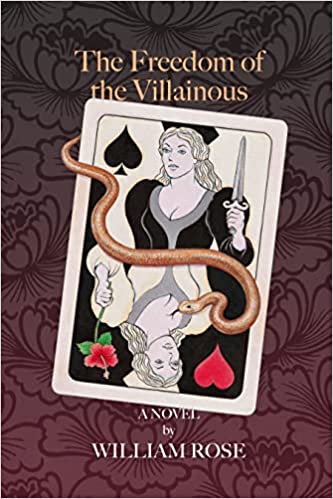

Marguerite Mercier, who would later, through marriage, ascend to Marguerite Comtesse de Bolvoir, landed at Whitby harbour in the early winter of 1864. She had sailed from France and had added the extra nautical miles to her journey so as to reach our North Yorkshire town directly, without need for further travelling by land.

She was 22 years old and was already a collector. Later to become a champion of art nouveau and the owner of many objects of great beauty, she was, at this early stage, simply a collector of events. For one so young, she had already formed a remarkable collection. Travelling through Europe, she savoured the cultures of great cities and, ever alert and eager, drew into her being those elements that marked each from the other, tasting and delighting in their contrasts. Each day was marked for adventure, and though the intensity could vary, some degree was required lest boredom set in. Marguerite did not find pleasure in the slow movement and rhythm of life that can appeal to the more contemplative soul. Stillness tended to alarm her and even to refer to “the soul” might here be an error. The excitements of life were her requirement and the portal offered by stillness beckoned to thoughts and feelings that she had decided to designate as alien. She already had considerable willpower and the early formations of a philosophy that served her well, though later it would come to rule rather than to serve.

An adventure could be born from a chance encounter. There were many fellow travellers, who, being of enquiring minds and of sufficient wealth, moved through the cities of Europe and beyond, even to Asia, Africa, and the Americas, and Marguerite, with a discernment uncommon for one so young, found ways of engaging the more interesting of these in conversation and even friendship, as far as the constant movement of the traveller would allow. Her presence in a hotel lounge, the foyer of a theatre, or the halls of an art gallery, would be noticed as if through an invisible force, one that is sometimes called charisma, though that term may not be sufficient. The powers that cause attraction are not always subject to definition.

Though such forces were at work, there were, as well, the more formal requirements when arriving in a strange city, and Marguerite would bring with her letters of introduction provided by her well-connected family. That her father was a high-ranking French diplomat added status to any request that his daughter might visit and perhaps stay for a period of time. Such requests would be couched within the understanding that his daughter was eager to learn more of the cultures and even the languages of the countries of Europe, and in this he was correct, though her manner of learning might not always have been as he intended. But, in truth, his disapprovals would go no further than an initial confrontation, which would soon lose its strength before the face that returned his gaze with not the slightest sign of yielding. Indeed, he feared his daughter.

For Marguerite, the traveller, each small encounter might offer something outside of the ordinary and a fresh stimulation. If it were of the intellect, she would converse, internalise, and retain the benefits of fresh knowledge, storing away the content of long and full conversations. Any suggestion of the amorous was happily added to the benefits. She took pleasure in her own charms and had realised, even as a child, their power of attraction; attributes that she soon came to utilise on becoming a woman.

And Marguerite was not to be frustrated. Her hunger for stimulation could be voracious, and those in her family who had observed her as an infant and watched the hungry baby grow into a demanding child and then a domineering adolescent had little difficulty in seeing an element in her development which had begun with the literal draining of three wet nurses, each of whom was unable to maintain the necessary supply for the infant girl, and who left the family service with not only a sense of failure, but exhaustion and defeat.

For Marguerite, the grown woman, each new day contained supplies, manifest or hidden, to be found and tasted and, if not worthy of consumption, to be spat out. Ridding herself of what she disliked came as easily as possessing what she desired.

It is indicative that I have begun with a detailed account of Marguerite and have yet to mention her sister, for she did not disembark at the port of Whitby alone. She was accompanied by Mariana. It can perhaps be already imagined that one such as Marguerite could have little room for the inclusion of another in the daily pursuit of her desires, and if such another should be a sibling the resistance would be far greater. But when we are to consider that Mariana was no ordinary sister, but an identical twin, the matter becomes more complex.

It was a complexity into which I was drawn, as it was my father who was to meet the sisters after their long journey and indeed to be their host for several weeks. Such is the tradition of old friendships between families, even when the friendship was forged long ago. My father had never met these sisters and had hardly known of them until the introductory letter from their own father arrived.

I should now introduce myself, or rather, introduce the youth who witnessed the arrival at Whitby of these remarkable twins, though I do so with concern, as I have yet to give a description of Mariana. But, given the nature of the sisters and their relationship, this is predictable, as one so dominated the other.

Such a difference in personality can hardly be imagined. To the observer, each movement, utterance, and expression of the one bore no resemblance to the other, and all this was weirdly incongruous since their facial and bodily features were as identical as nature could allow.

I write now with the impressions of the 17-year-old who first set eyes on them, tempered by the considered thinking and experience that has taken place in the 40 years that have followed. We had lived in Whitby for four years. My father was an artist who had achieved great success in the painting of portraits. There were landscapes too, but without doubt his skill at expressively depicting the human face above an extravagantly dressed figure was the key to his reputation and wealth. He was also adept at financial affairs so that the spectre of insolvency that often stalks the professional artist was seen off before his middle age. Indeed, our move to Whitby was an early retirement from his busy London life, though it was in keeping with his usual good fortune, that he then found a rich stream of commissions from the Northern industrialists whose new wealth and status deemed the portrait of themselves and their families a social requirement. He happily acquiesced to this new visitation from success.

That portrait painting was his main occupation can suggest frustration with his creative vision. Not at all. He was an immensely fulfilled and contented man with a personality so calm, yet open to pleasure, that he seemed blessed by complete mental health.

A health that was ruined by that winter of 1864 and the events that followed. I know that no man is immune, even one as steadfast as my father, and his sensitivity to that indefinable concoction that drives the creative spirit and that had graced and elevated his portraits was also his undoing. Sadly, it left him beguiled and cast into failure.

Chapter 2

The portrait

In my current profession as a doctor of the mind, I try to recognise and define the components and parameters of a human life, yet I know that such aims cannot reach to the essence of the self, something as unknowable and wondrous as the origin of our universe and its countless stars. Like the stars, some selves burn brighter, or bend and ripple the space around them, and this can be a cause for joy, though sometimes despair, and even ruin. We know that there are stars that are twinned and that, endlessly, they will circle each other, captured by gravity, nature’s irresistible force. The two sisters who came to Whitby were also subject to the powers of nature, forever coupled through their sharing of a womb and the overlap of physicality into which they were born. Twin stars and twin sisters, with lives so deeply interlinked, but with souls so dissimilar, that it was as if one had been torn from the other leaving each with the qualities that the other sorely lacked. And my father welcomed this strange dynamic into our home.

And then, he wished to paint it, not as a commission, but because it excited him, and when completed, it remained in his studio, whilst the bravura of its execution gradually degraded into a baleful reminder that destructiveness can hide within beauty and that fascination can be a deadly chimera.

The painting hung upon a wall of the great studio, in a corner that I always felt was its most intimate space. The light was softer there and shaded from the plain, white brightness of the north-facing windows. It was in that corner that my father had placed an ancient, worn, armchair, covered in rough material of fading reds and golds, as if wrapped in tapestry, and here he would sit to smoke his white, clay pipes and contemplate the current work that rested waiting upon an easel, and those others, half or nearly finished, that hung upon the walls. The portrait of the twins seemed to be floating there in the soft light, unattached to anything, and its gentle luminescence was a product of the great skill and vision of my father, who had set the scene beside a calm lake and the time of day was early evening with just the beginnings of twilight.

And so, I can let the portrait and my father’s vision now serve me as I describe the two sisters. They are, indeed, identical, but that would be to greatly devalue my father’s work. It was as if his whole considerable effort in creating the painting had been to diversify, to search for, and to find the very essence of each and to celebrate the difference. He sought fulfilment in this need to observe and enquire, and such enquiry is so well served by the many hours spent gazing at a subject who must remain completely still.

And the movement of the brush upon the canvas, the mixing of the colours, all the formal rhythmic process, allowing the mind to roam freely and to be surprised and then rest upon the unexpected, even sometimes the extraordinary. And so, in this, my father was an adventurer, an explorer searching for clarity, but not averse to finding the uncanny in the strange phenomena of the two twins. For how can we who are singletons imagine a life lived with one who was there from conception, who shared our time of birth, laid simultaneous claims upon our mother’s breasts, and whose existence might predetermine our very destiny. How close the word identical is to identity and how ironic that it should be so! Does identical allow for identity, which we see as such a singular thing?

All of this was surely a fascination for my father; reason enough for the many hours of work he spent upon this painting, though surely it was an unworthy object of his great endeavour since the complexity of his subjects was almost his undoing.

With his personal interest in the sisters, there was to be an element of theatre in the studio, as, with them, he freely and spontaneously voiced any imaginative ideas that came into his mind, accompanied by the most expressive of gestures and bodily movements.

It was Marguerite who could respond in a kindred fashion, so that, between them, a dance of words might ensue, sometimes warmly embracing, at others challengingly intertwined, and on occasions they would declare their distance with cut, thrust, and parry. He knew that there could never be a small encounter with this formidable young woman.

There was, though, a softly muted counterpoint provided by Mariana, which, through her presence rather than her few words, strangely added a lustre to the proceedings, as if an ethereal melody could just be heard, almost imperceptible, but tantalisingly there.

And so, he placed Marguerite at the front of the canvas, full and imposing, and defiantly meeting the eyes of any viewer who should deign to show interest. She looked magnificent, though to my mind, and maybe later events have affected my memory, with a hint of brutality. I think now of those later paintings of women by my father’s friend Rossetti: magnificent, voluptuous, and absorbing orchids. I do believe that the feminine was eating Mr Rossetti up, though he loved it so. For my father, this was not a trend, but occurred in this one instance. And he clothed Marguerite in black silk, trimmed with lace as if a funeral had become confused with a grand ball. She wore black gloves that covered her forearms, and her light brown hair was free of any hat and was splendidly coiffured with generous curls that gently kissed her cheeks.

He showed her height, which was true to life, though she would have been impressive without it. Her face was broad, her eyes wide apart, the mouth large with generous lips, and there were freckles which could only add irony to such an imposing vision.

My father portrayed her in a black dress as it suited his idea, but it was also in keeping with the scheme of the painting. The setting was a lakeside and the time of day, with its mood and subtle lighting, was the early evening with a hint of the softness of twilight. On looking at the painting, one could almost hear the occasional sounds that might drift across a lake or open countryside; strange, rare, and clear against a background of silence. The tones were of the dark grey and almost black of the water, rising gently up into lighter blue-grey, and then higher into a sky that still retained the palest of blue strips between clouds of white and grey. Somewhere, there would have been a streak of setting sun above the horizon, but this was not within the plain of the picture.

And behind the figure of Marguerite, by several yards and right at the edge of the lake with her feet just hidden by water, was Mariana, not dressed in black but in the colours of twilight, soft greys, with a little highlighting of white and the garment was more of a smock, or the plainest mediaeval robe that a lady of grace, but simplicity, might wear. Marguerite looked resoundingly of her time, and Mariana was of the era of King Arthur. In fact, the lake she stood before could have been the one whose waters parted to allow the hand to rise and receive the thrown sword of the dying king. Her body was shaped as by the brush of an artist of Japan, as if it were the product of one sensual and uninterrupted stroke as she gracefully leant to one side, an arm descending to the water and reaching into it for something she seemed to desire or need. Unlike Marguerite, her hair hung loosely, tied lightly by a bow, so that it rested upon one shoulder and could still descend to her waist.

In the distance, one lone bird, a sea gull, was airborne in the sky. And that was the painting in its fullness; it needed no more.

Chapter 3

The meeting in the square

A chance and strange meeting took place in a square in Almeria in South East Spain. It was in one of those many plazas that offer relief from the main thoroughfares or that provide pleasant interludes as one strolls through narrow streets in the antique parts of such cities.

It was an evening in June and 18 months before the twins’ visit to us in Whitby. The two young women had travelled to Almeria in May, and now the summer heat was urging them to retreat to the north of the country, and perhaps even to return to Paris. But, just then, as they walked in the square, the sun had dropped below the roofs of the buildings, and they were softly wrapped by the warm air of the evening. All was very still and they were alone apart from a black dog that sniffed its way across the plaza before disappearing within the shadows at its edge.

The young women did not dress in identical clothes. That habit had belonged more to the vision of their family and had long since been abandoned. It would, anyway, have been incongruous for such different personalities. Marguerite was ever the extrovert, and quite ready to bare her arms and neck in such a warm climate. The dress she wore now though rested upon the tips of her shoulders but covered her arms, expanding out at the wrists where it was fringed with lace. All was in black patterned silk, held tightly at the waist before flowing freely and generously downwards to just brush the ground. She was bare headed and in her light brown hair she had fastened a red rose. All was completely inappropriate for a French girl on an evening stroll, but Marguerite could accomplish such looks with panache, and anyway she was enjoying herself as “Dona Marguerita.”

All about Mariana was its opposite: a simple white dress of cotton, her forearms just showing the golden tan acquired during their stay. Her face was shaded by a white hat with a large brim, and on her feet were cream leather sandals.